Difference between revisions of "Heat conduction" - New World Encyclopedia

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

|||

| (11 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{Images OK}}{{Approved}} | + | {{Copyedited}}{{Images OK}}{{Approved}} |

| − | '''Heat conduction''', or '''thermal conduction''', is the spontaneous [[heat transfer|transfer of thermal energy]] through matter, from a region at higher [[temperature]] to a region at lower temperature | + | '''Heat conduction''', or '''thermal conduction''', is the spontaneous [[heat transfer|transfer of thermal energy]] through matter, from a region at higher [[temperature]] to a region at lower temperature. It thus acts to equalize temperature differences. It is also described as heat energy transferred from one material to another by direct contact. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | Thermal energy, in the form of continuous random motion of particles of matter, is transferred by the same [[Coulomb's law|coulomb forces]] that act to support the structure of matter. For this reason, its transfer can be said to occur by physical contact between the particles. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

Besides conduction, heat can also be transferred by [[thermal radiation|radiation]] and [[convection]], and often more than one of these processes may occur in a given situation. | Besides conduction, heat can also be transferred by [[thermal radiation|radiation]] and [[convection]], and often more than one of these processes may occur in a given situation. | ||

== Fourier's law == | == Fourier's law == | ||

| − | The '''law of heat conduction''', also known as '''Fourier's law''', states that the time rate of [[heat transfer]] through a material is [[Proportionality (mathematics)|proportional]] to the negative [[gradient]] in the temperature and to the area at right angles, to that gradient, through which the heat is flowing. | + | The '''law of heat conduction''', also known as '''Fourier's law''', states that the time rate of [[heat transfer]] through a material is [[Proportionality (mathematics)|proportional]] to the negative [[gradient]] in the temperature and to the area at right angles, to that gradient, through which the heat is flowing. This law can be stated in two equivalent forms: |

| + | * The integral form, in which one considers the amount of energy flowing into or out of a body as a whole. | ||

| + | * The differential form, in which one considers the local flows or [[Heat flux|fluxes]] of energy. | ||

=== Differential form === | === Differential form === | ||

| − | In the differential formulation of Fourier's law, the fundamental quantity is the local [[heat flux]] <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q}</math>. This is the amount of energy flowing through an infinitesimal oriented surface per unit of time. The length of <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q}</math> is given by the amount of energy per unit of time and the direction is given by the vector perpendicular to the surface. As a vector equation this leads to | + | In the differential formulation of Fourier's law, the fundamental quantity is the local [[heat flux]] <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q}</math>. This is the amount of energy flowing through an infinitesimal oriented surface per unit of time. The length of <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q}</math> is given by the amount of energy per unit of time, and the direction is given by the vector perpendicular to the surface. As a vector equation, this leads to: |

| − | : <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q} | + | : <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q} = - k \overrightarrow{\nabla} T</math> |

| − | where ( | + | where (showing the terms in [[SI]] units) |

| − | : <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q}</math> is the local [[heat flux]], | + | : <math>\overrightarrow{\phi_q}</math> is the local [[heat flux]], in Watts per square meter ([[Watt|W]]•[[Meter|m]]<sup>−2</sup>), |

| − | : <math>k</math> is the material's [[thermal | + | : <math>k</math> is the material's [[thermal conductivity]], in Watts per meter per degree Kelvin ([[Watt|W]]•[[Meter|m]]<sup>−1</sup>•[[Kelvin|K]]<sup>−1</sup>), |

| − | : <math>\nabla T</math> is the temperature gradient, | + | : <math>\nabla T</math> is the temperature gradient, in degrees Kelvin per meter ([[Kelvin|K]]•[[Metre|m]]<sup>−1</sup>) |

| − | Note that the thermal conductivity of a material generally varies with temperature, but the variation can be small over a significant range of temperatures for some common materials. In anisotropic materials the thermal conductivity typically varies with direction | + | Note that the thermal conductivity of a material generally varies with temperature, but the variation can be small over a significant range of temperatures for some common materials. In anisotropic materials, the thermal conductivity typically varies with direction; in this case, <math>k</math> is a tensor. |

=== Integral form === | === Integral form === | ||

| Line 28: | Line 30: | ||

: <math> \frac{\partial Q}{\partial t} = -k \oint_S{\overrightarrow{\nabla} T \cdot \,\overrightarrow{dS}} </math> | : <math> \frac{\partial Q}{\partial t} = -k \oint_S{\overrightarrow{\nabla} T \cdot \,\overrightarrow{dS}} </math> | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | where (showing the terms in [[SI]] units) | |

| + | : <math>\frac{\partial Q}{\partial t}</math> is the amount of heat transferred per unit time, in Watts ([[Watt|W]]) or Joules per second ([[Joule|J]]•[[Second|s]]<sup>-1</sup>), | ||

| + | : <math>S</math> is the surface through which the heat is flowing, in square meters ([[Meter|m]]<sup>2</sup>). | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:Linear Heat flow.svg|thumb|200px|Diagram of linear heat flow, from a hotter surface (red) to a cooler surface (blue).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | Consider a simple linear situation (see diagram), where there is uniform temperature across equally sized end surfaces and the sides are perfectly insulated. In such a case, [[Integral|integration]] of the above [[differential equation]] gives the heat flow rate between the end surfaces as: | ||

: <math> \frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t} = -k A \frac{\Delta T}{\Delta x} </math> | : <math> \frac{\Delta Q}{\Delta t} = -k A \frac{\Delta T}{\Delta x} </math> | ||

| + | |||

where | where | ||

: ''A'' is the cross-sectional surface area, | : ''A'' is the cross-sectional surface area, | ||

: <math>\Delta T</math> is the temperature difference between the ends, | : <math>\Delta T</math> is the temperature difference between the ends, | ||

| − | : <math>\Delta x</math> is the distance between the ends | + | : <math>\Delta x</math> is the distance between the ends. |

| − | |||

| − | + | This law forms the basis for derivation of the [[heat equation]]. | |

| − | + | The [[R-value (insulation)|R-value]] is the unit for heat resistance, the reciprocal of heat conductance. | |

| − | : <math> U = \frac{k}{\Delta x}, \quad</math> | + | |

| − | where | + | [[Ohm's law]] is the electrical analog of Fourier's law. |

| − | + | ||

| − | Fourier's law can also be stated as: | + | == Conductance and resistance == |

| + | |||

| + | The conductance (<math>U</math>) can be defined as: | ||

| + | : <math> U = \frac{k}{\Delta x}, \quad</math> | ||

| + | where the units for <math>U</math> are given in W/(m<sup>2</sup> K). | ||

| + | |||

| + | Thus, Fourier's law can also be stated as: | ||

: <math>Q = U A\, \Delta T.</math> | : <math>Q = U A\, \Delta T.</math> | ||

| − | The reciprocal of conductance is resistance, R | + | The reciprocal of conductance is resistance, R. It is given by: |

| − | : <math> R = \frac{A\, \Delta T}{Q}, \quad</math> | + | : <math> R = \frac{1}{U} = \frac{A\, \Delta T}{Q}, \quad</math> |

| − | + | Resistance is additive when several conducting layers lie between the hot and cool regions, because ''A'' and ''Q'' are the same for all layers. In a multilayer partition, the total conductance is related to the conductance of its layers by the following equation: | |

: <math>\frac{1}{U} = \frac{1}{U_1} + \frac{1}{U_2} + \frac{1}{U_3}+ \cdots</math> | : <math>\frac{1}{U} = \frac{1}{U_1} + \frac{1}{U_2} + \frac{1}{U_3}+ \cdots</math> | ||

| Line 65: | Line 75: | ||

===Intensive-property representation=== | ===Intensive-property representation=== | ||

| − | The previous conductance equations written in terms of [[Intensive and extensive properties|extensive properties]], can be reformulated in terms of | + | The previous conductance equations written in terms of [[Intensive and extensive properties|extensive properties]], can be reformulated in terms of intensive properties. |

| − | <!-- material was posted as a revision suggestion for the article | + | <!-- material was posted as a revision suggestion for the article —> |

Ideally, the formulae for conductance should produce a quantity with dimensions independent of distance, like [[Ohm's Law]] for electrical resistance: <math>R = V/I\,\!</math>, and conductance: <math> G = I/V \,\!</math>. | Ideally, the formulae for conductance should produce a quantity with dimensions independent of distance, like [[Ohm's Law]] for electrical resistance: <math>R = V/I\,\!</math>, and conductance: <math> G = I/V \,\!</math>. | ||

| Line 74: | Line 84: | ||

For Heat, | For Heat, | ||

| − | : <math> U = \frac{k A} {\Delta x}, \quad</math> | + | : <math> U = \frac{k A} {\Delta x}, \quad</math> |

where ''U'' is the conductance. | where ''U'' is the conductance. | ||

| Line 94: | Line 104: | ||

* [[Heat]] | * [[Heat]] | ||

* [[Thermal conductivity]] | * [[Thermal conductivity]] | ||

| − | |||

* [[Convection]] | * [[Convection]] | ||

* [[Thermal radiation]] | * [[Thermal radiation]] | ||

| Line 102: | Line 111: | ||

* Baierlein, Ralph. 2003. ''Thermal Physics''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521658381 | * Baierlein, Ralph. 2003. ''Thermal Physics''. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521658381 | ||

* Halliday, David, Robert Resnick, and Jearl Walker. 1997. ''Fundamentals of Physics'', 5th ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471105589 | * Halliday, David, Robert Resnick, and Jearl Walker. 1997. ''Fundamentals of Physics'', 5th ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471105589 | ||

| − | * Serway, Raymond A. and John W. Jewett. 2004. ''Physics for Scientists and Engineers.'' Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0534408427 | + | * Serway, Raymond A., and John W. Jewett. 2004. ''Physics for Scientists and Engineers.'' Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0534408427 |

| − | * Srivastava, G. P. 1990. ''The Physics of Phonons.'' Bristol: A. Hilger. ISBN 0852741537 | + | * Srivastava, G.P. 1990. ''The Physics of Phonons.'' Bristol: A. Hilger. ISBN 0852741537 |

| − | * Young, Hugh D. and Roger A. Freedman. 2003. ''Physics for Scientists and Engineers''. San Fransisco, CA: Pearson. ISBN 080538684X | + | * Young, Hugh D., and Roger A. Freedman. 2003. ''Physics for Scientists and Engineers''. San Fransisco, CA: Pearson. ISBN 080538684X |

== External links == | == External links == | ||

| − | * [http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/NewtonsLawOfCooling/ Newton's Law of Cooling] | + | All links retrieved December 12, 2017. |

| + | * [http://demonstrations.wolfram.com/NewtonsLawOfCooling/ Newton's Law of Cooling] Wolfram Demonstrations Project. | ||

[[Category:Physical sciences]] | [[Category:Physical sciences]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:31, 12 December 2017

Heat conduction, or thermal conduction, is the spontaneous transfer of thermal energy through matter, from a region at higher temperature to a region at lower temperature. It thus acts to equalize temperature differences. It is also described as heat energy transferred from one material to another by direct contact.

Thermal energy, in the form of continuous random motion of particles of matter, is transferred by the same coulomb forces that act to support the structure of matter. For this reason, its transfer can be said to occur by physical contact between the particles.

Besides conduction, heat can also be transferred by radiation and convection, and often more than one of these processes may occur in a given situation.

Fourier's law

The law of heat conduction, also known as Fourier's law, states that the time rate of heat transfer through a material is proportional to the negative gradient in the temperature and to the area at right angles, to that gradient, through which the heat is flowing. This law can be stated in two equivalent forms:

- The integral form, in which one considers the amount of energy flowing into or out of a body as a whole.

- The differential form, in which one considers the local flows or fluxes of energy.

Differential form

In the differential formulation of Fourier's law, the fundamental quantity is the local heat flux . This is the amount of energy flowing through an infinitesimal oriented surface per unit of time. The length of is given by the amount of energy per unit of time, and the direction is given by the vector perpendicular to the surface. As a vector equation, this leads to:

where (showing the terms in SI units)

- is the local heat flux, in Watts per square meter (W•m−2),

- is the material's thermal conductivity, in Watts per meter per degree Kelvin (W•m−1•K−1),

- is the temperature gradient, in degrees Kelvin per meter (K•m−1)

Note that the thermal conductivity of a material generally varies with temperature, but the variation can be small over a significant range of temperatures for some common materials. In anisotropic materials, the thermal conductivity typically varies with direction; in this case, is a tensor.

Integral form

By integrating the differential form over the material's total surface , we arrive at the integral form of Fourier's law:

where (showing the terms in SI units)

- is the amount of heat transferred per unit time, in Watts (W) or Joules per second (J•s-1),

- is the surface through which the heat is flowing, in square meters (m2).

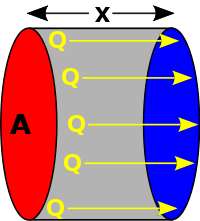

Consider a simple linear situation (see diagram), where there is uniform temperature across equally sized end surfaces and the sides are perfectly insulated. In such a case, integration of the above differential equation gives the heat flow rate between the end surfaces as:

where

- A is the cross-sectional surface area,

- is the temperature difference between the ends,

- is the distance between the ends.

This law forms the basis for derivation of the heat equation.

The R-value is the unit for heat resistance, the reciprocal of heat conductance.

Ohm's law is the electrical analog of Fourier's law.

Conductance and resistance

The conductance () can be defined as:

where the units for are given in W/(m2 K).

Thus, Fourier's law can also be stated as:

The reciprocal of conductance is resistance, R. It is given by:

Resistance is additive when several conducting layers lie between the hot and cool regions, because A and Q are the same for all layers. In a multilayer partition, the total conductance is related to the conductance of its layers by the following equation:

So, when dealing with a multilayer partition, the following formula is usually used:

When heat is being conducted from one fluid to another through a barrier, it is sometimes important to consider the conductance of the thin film of fluid which remains stationary next to the barrier. This thin film of fluid is difficult to quantify, its characteristics depending upon complex conditions of turbulence and viscosity, but when dealing with thin high-conductance barriers it can sometimes be quite significant.

Intensive-property representation

The previous conductance equations written in terms of extensive properties, can be reformulated in terms of intensive properties.

Ideally, the formulae for conductance should produce a quantity with dimensions independent of distance, like Ohm's Law for electrical resistance: , and conductance: .

From the electrical formula: , where ρ is resistivity, x = length, A cross sectional area, we have , where G is conductance, k is conductivity, x = length, A cross sectional area.

For Heat,

where U is the conductance.

Fourier's law can also be stated as:

analogous to Ohm's law: or

The reciprocal of conductance is resistance, R, given by:

analogous to Ohm's law:

The sum of conductances in series is still correct.

See also

- Heat

- Thermal conductivity

- Convection

- Thermal radiation

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baierlein, Ralph. 2003. Thermal Physics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521658381

- Halliday, David, Robert Resnick, and Jearl Walker. 1997. Fundamentals of Physics, 5th ed. New York: Wiley. ISBN 0471105589

- Serway, Raymond A., and John W. Jewett. 2004. Physics for Scientists and Engineers. Belmont, CA: Thomson-Brooks/Cole. ISBN 0534408427

- Srivastava, G.P. 1990. The Physics of Phonons. Bristol: A. Hilger. ISBN 0852741537

- Young, Hugh D., and Roger A. Freedman. 2003. Physics for Scientists and Engineers. San Fransisco, CA: Pearson. ISBN 080538684X

External links

All links retrieved December 12, 2017.

- Newton's Law of Cooling Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.