Greene, Graham

m ({{Contracted}}) |

|||

| (65 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Paid}}{{Approved}}{{Submitted}}{{copyedited}}{{Images OK}} |

| − | + | {{Epname|Greene, Graham}} | |

| − | {{ | + | {{Infobox Writer |

| − | + | | honorific_suffix = {{postnominals|country=GBR|OM|CH|size=100%}} | |

| − | + | | name = Graham Greene | |

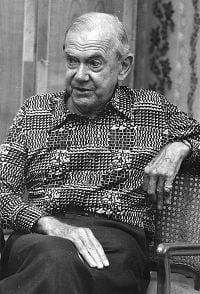

| + | | image = Graham Greene angol író, 1975 Fortepan 84697.jpg | ||

| + | | image_size = | ||

| + | | caption = Greene in 1975 | ||

| + | | pseudonym = | ||

| + | | birth_name = Henry Graham Greene | ||

| + | | birth_date = {{birth date|mf=yes|1904|10|2}} | ||

| + | | birth_place = [[Berkhamsted]], [[Hertfordshire]], England | ||

| + | | death_date = {{death date and age|mf=yes|1991|4|3|1904|10|2}} | ||

| + | | death_place = [[Vevey]], Switzerland | ||

| + | | Spouse = {{marriage|[[Vivien Dayrell-Browning]]|1927|1947|end={{abbr|sep.|separated}}}} | ||

| + | | Domestic partner(s) = [[Catherine Walston, Lady Walston]] (1946–1966)<br />Yvonne Cloetta (1966–1991) | ||

| + | | Children = Lucy Caroline (b. 1933)<br />Francis (b. 1936) | ||

| + | | alma_mater = [[Balliol College, Oxford]] | ||

| + | | occupation = Writer | ||

| + | | period = 1925–1991 | ||

| + | | genre= [[literary fiction]], [[Thriller (genre)|thriller]] | ||

| + | | signature = | ||

| + | | website = | ||

| + | }} | ||

| − | + | '''Henry Graham Greene,''' [[Order of Merit|OM]], [[Order of the Companions of Honour|CH]] (October 2, 1904 – April 3, 1991), was a visionary [[England|English]] [[novelist]], [[playwright]], [[short story]] writer, and [[critic]]. He also penned several screenplays for Hollywood, and in turn, many of his works, which are full of action and suspense, have been made into films. Greene's stylistic work is known for its explorations of moral issues dealt with in a political setting. His novels gained him a reputation as one of the most widely read writers of the twentieth century. | |

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Graham Greene, known as a world-traveler, would often seek out adventure to fuel his stories and experience the political world of various nations up close. Many of his writings are centered on the religious beliefs of [[Roman Catholic|Roman Catholicism]], although he detested being described as a "Catholic novelist" rather than as a "novelist who happened to be Catholic." His focus on religion did not deter readers or jade Greene's writings, but on the contrary, in novels such as ''Brighton Rock,'' ''The Heart of the Matter,'' ''The End of the Affair,'' ''Monsignor Quixote,'' and his famous work ''The Power and the Glory,'' it only made them more poignant. His intense focus on moral issues, politics, and religion, mixed with suspense and adventure, became the trademark of Graham Greene's ingenious works. | ||

==Life and work== | ==Life and work== | ||

| + | |||

===Childhood=== | ===Childhood=== | ||

| − | Greene was born in | + | [[File:St. John’s boarding house Berkhamsted 1.jpg|thumb|400px|St. John’s, a boarding house of Berkhamsted School in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire; Graham Greene was born here in 1904 when his father was housemaster]] |

| + | Graham Greene was the fourth born child to Charles Henry and Marion Raymond Greene. Greene was raised in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, and was a very shy and sensitive child. Graham was born into a large and influential family. His parents were first cousins, and were related to the writer [[Robert Louis Stevenson]]. His father was related to the owners of the large and influential Greene King brewery. The more distant relations of the family were comprised of various bankers, barristers, and businessmen. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Graham's siblings also made significant individual marks on the world. Greene's younger brother, Hugh served as the Director-General of the [[British Broadcasting Company]] (BBC), and his older brother, Raymond, was an eminent doctor and mountaineer, involved in both the 1931 Kamet and 1933 Everest expeditions. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In 1910, Charles Greene succeeded Dr. [[Thomas Fry]] as headmaster at Berkhamsted School, and Graham, along with his brothers, began attending Berkhamsted. Greene's years as a student at the school were full of profound unhappiness. Graham was constantly bullied, beat-up, mocked, and made fun of. He often skipped classes to find solitude in reading. His escapes only garnered him censure from his father, and he found that he could not balance the torrid treatment by his peers and the stern treatment by his father. During the three years at Berkhamsted, it is reported that Greene attempted [[suicide]] on several different occasions. Greene claimed that often he would sit and play [[Russian roulette]]—but Michael Shelden's biography of the author discredits this claim. | ||

| − | + | One day, Greene simply left school, leaving a letter for his parents that said he would not return. This led his parents sending him to a therapist in London to deal with his [[depression]]. Greene was seventeen at the time. His therapist, [[Kenneth Richmond]], encouraged Greene to write and even introduced Greene to a few of his literary friends, like [[Walter de la Mare]]. | |

| − | He | + | Greene returned to finish his high school education at Berkhamsted. He continued on at Balliol College, Oxford, where he published more than sixty stories, articles, reviews, and poems in the student magazine, ''Oxford Outlook''. He reached a milestone in his life when his first volume of poetry was published in 1925, while he was still an undergraduate. In 1926, Graham Greene converted to Roman Catholicism, later stating that "I had to find a religion… to measure my evil against." |

===Early career=== | ===Early career=== | ||

| − | + | In 1926, Greene graduated and began a career in [[journalism]]. His first post was in Nottingham, a city he depicted in several of his novels, and while working he received a letter from [[Vivien Greene|Vivien Dayrell-Browning]], also a Catholic, who had written to Greene and corrected him on points of Catholic doctrine. Greene was intrigued and they began a correspondence. Greene moved to London that same year and began working as an editor of ''The Times'' as well as ''The Spectator,'' where he was employed as a film critic and a literary editor until 1940. | |

| + | |||

| + | In 1927, Greene and Vivien were married, although, Greene is the first to admit that he was not a family man and reportedly disliked children. Greene was unfaithful to Vivien and the marriage fell apart in 1948. Despite his feelings about children, the couple had two, Lucy (1933) and Francis (1936). Throughout his marriage, Greene had a number of affairs with various women. Often his mistresses were married women who lived in different countries. In 1948, Greene left Vivien for [[Catherine Walston]], even though the couple never officially filed for divorce. | ||

===Novels and other works=== | ===Novels and other works=== | ||

| − | Greene | + | Graham Greene published his first novel in 1929, and with the publication of ''The Man Within,'' he began devoting all his time to writing. Greene quit his full-time post and supplemented his income with freelance jobs. Along with working for ''The Spectator,'' he also co-edited the magazine, ''Night and Day.'' In 1937, the magazine closed down after Greene wrote a review of ''Wee Willie Winkie,'' a film starring [[Shirley Temple]]. In the review, Greene wrote that Temple displayed "a certain adroit coquetry which appealed to middle-aged men." This comment caused the magazine to lose a libel case, and it remains the first criticism in the entertainment industry of the sexualization of children. |

| − | His | + | His first real success came with the publication of ''Stamboul Train'' in 1932 (adapted into the film, ''Orient Express,'' in 1934). He met with other success as he continued to write, often having two very distinct audiences. There was the audience that loved Greene's thrillers and suspense novels like ''Brighton Rock'' and there was a completely different audience who admired Greene's genius in literary novels such as ''The Power and the Glory.'' Considered the best novel of his career, it was both acclaimed (Hawthornden Prize winner in 1941) and condemned (by the Vatican). While Greene was able to divide his works into two genres, his reputation as a literary writer gained him more recognition. |

| − | + | Greene's diverse talent was recognized when his mystery/suspense novels began to be valued as much as his more serious novels. Such works as ''The Human Factor,'' ''The Comedians,'' ''Our Man in Havana,'' and ''The Quiet American'' showed Greene's ability to create an entertaining and thrilling story and combine it with serious insight, depth of character, and universal themes. | |

| − | + | With the success of his books, Greene expanded his literary repertoire to short stories and plays. He also wrote many screenplays, his most famous one being ''The Third Man''. In addition, several of his books were made into films, including 1947's ''Brighton Rock'' and ''The Quiet American''(2002), set in Vietnam and starring [[Michael Caine]] (for which Caine was nominated for an Oscar). | |

| + | |||

| + | Greene was considered for the [[Nobel Prize for Literature]] several times, but he never received the prize. Some attributed this to the very fact that he was so popular, as the scholarly elite disliked this trait. His religious themes were also thought to have played a role in whether or not he was awarded the honor, as it might have alienated some of the judges. | ||

| − | Greene | + | ===Writing style and themes=== |

| + | {{readout||right|250px|Graham Greene's intense focus on moral issues, politics, and religion, mixed with suspense and adventure, became the trademark of his popular novels.}} | ||

| + | Greene's writings were innovative, not only in the religious themes he incorporated, but also in his avoidance of popular modernist experiments. His writings were characterized by a straightforward and clear manner. He was a realist, yet his technique created suspenseful and exciting plots. His word combinations led many to feel like they were reading something cinematic. His descriptions were full of imagery, yet he was not superfluous in his word usage, a trait that was admired by his audience and contributed to his wide popularity. | ||

| − | Greene's | + | Another facet of Greene's writing style was the ability he had to depict the internal struggles that his characters faced, as well as their outward struggles. His characters were deeply spiritual with emotional depth and intelligence. They each faced universal struggles, but Greene portrayed them as highly individualistic. The reader cares deeply for the characters facing rampant cynicism and world-weariness. His characters often faced living conditions that were harsh, wretched and squalid. The settings of Greene's stories were poverty stricken countries like Mexico, West Africa, Vietnam, Haiti, Argentina—countries that were hot, humid, and abject. This trait led to the coining of the expression "Greeneland" for describing such settings. |

| − | + | Even with the most destitute of circumstances Greene's characters had the values and beliefs of Catholicism explicitly present in their lives. Greene was critical of the literature of his time for its dull, superficial characters who "wandered about like cardboard symbols through a world that is paper-thin." He felt that literature could be saved by adding religious elements to the stories. He felt the basic struggle between good and evil, the basic beliefs in right and wrong, the realities of sin and grace, were all tools to be used in creating a more sensitive and spiritual character. Greene believed that the consequences of evil were just as real as the benefits of being good. [[V. S. Pritchett]] praised Greene, saying that he was the first English novelist since [[Henry James]] to present, and grapple with, the reality of evil.<ref>Edward Short, [https://www.crisismagazine.com/2005/the-catholic-novels-of-graham-greene The Catholic Novels of Graham Greene] ''Crisis Magazine'', April 1, 2005. Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> This ever present portrayal of evil was scorned by the leading theologian of the day, [[Hans Urs von Balthasar]], who said the Greene had given sin a certain "mystique." Greene not only dealt with the opposites of sin and virtue, but he explored many other Christian aspects of life as well, such as the value of faith, peace, and joy. Greene received both praise and criticism from Catholic writers and scholars. | |

| − | Greene | + | |

| + | As Greene grew older, his writings changed. No longer did he focus as intently on religious views. Instead, his focus became more wide-spread and approachable to a broader audience. He turned to a more "humanistic" viewpoint. In addition to this, he outwardly rejected many of the orthodox Catholic teachings he had embraced earlier in his life. Readers of his work began to see that the [[protagonist]]s were much more likely to be believers in Communism rather than Catholicism. | ||

| − | Greene's were | + | Greene's political views were different from other "Catholic writers" of the time, like [[Evelyn Waugh]] and [[Anthony Burgess]]. While they maintained a strictly right-winged agenda, Greene was always leaning left, and his travels influenced these ideas. Though many claim that politics did not interest Greene, his novels all began to reflect on and criticize American imperialism. Greene became a sympathizer with those who opposed the American government, like the Cuban leader [[Fidel Castro]].<ref>Tom Miller, [https://www.washingtonpost.com/archive/opinions/1991/04/14/sex-spies-and-literature/77b162a4-2d48-4d5c-8dc6-3c44e9ebebd0/ Sex, Spies and Literature] ''The Washington Post'', April 14, 1991. Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> |

| − | + | ===Travel=== | |

| + | During [[World War II]], Greene began to travel extensively; this travel would play a major part in the rest of his life. In fact, it was his travels and the people he met in various countries that inspired many of his plots, themes, and characters. In 1938, for example, the Roman Catholic Church funded Greene's trip to [[Mexico]]. The purpose of this trip was for Greene to observe and write about the effects of a forced anti-Catholic campaign against secularization. This event led to Greene writing ''The Lawless Roads'' (or ''Another Mexico,'' as it was known in America) and it formed the core of the fictional novel, ''The Power and the Glory.'' | ||

| − | + | During World War II, a notorious double agent, [[Kim Philby]] recruited Greene to work for England's own [[MI6]]. This stint in espionage fueled Greene's desire to travel, as well as provided him with memorable and intriguing characters. Greene became obsessed with traveling to the "wild and remote" places of the world. His travels led him to François Duvalier's [[Haiti]], where he set his 1966 novel, ''The Comedians''. Greene became so well-known in Haiti that the proprietor of the Hotel Oloffson in Port-au-Prince, named a room in the hotel in honor of Greene. After the war ended, he continued to travel as a free-lance journalist. He spent a long period on the French Riviera, in particular, Nice. He also made several anti-American comments during his travels, thus opening doors to Communist leaders like Fidel Castro and [[Ho Chi Minh]], whom he interviewed. Greene's close friend, Evelyn Waugh, wrote a letter in support of Greene as "a secret agent on our side and all his buttering up of the Russians is 'cover'." | |

| + | <blockquote> | ||

| + | There is so much weariness and disappointment in travel that people have to open up—in railway trains, over a fire, on the decks of steamers, and in the palm courts of hotels on a rainy day. They have to pass the time somehow, and they can pass it only with themselves. Like the characters of [[Anton Chekhov]] they have no reserves—you learn the most intimate secrets. You get an impression of a world peopled by eccentrics, of odd professions, almost incredible stupidities, and, to balance them, amazing endurances (Graham Greene, ''The Lawless Roads,'' 1939).</blockquote> | ||

| − | + | ===Final years and death=== | |

| + | Greene published two volumes of his autobiography, '' A Sort of Life'' in 1971, and ''Ways of Escape'' in 1980. | ||

| − | + | In, ''J'Accuse—The Dark Side of Nice'' (1982), one of his last works, he wrote about the travesties he saw while living in Nice. He wrote specifically about the [[organized crime]] that corrupted the very foundations of the civic government and the severe judicial and police corruption abounding in the society. His writings were not ignored, and this led to a [[libel]] case, which he lost. Vindication came in 1994, three years after his death, when the former mayor of Nice, [[Jacques Médecin]], was finally convicted and sentenced to jail for several counts of corrupt behavior and criminal actions. | |

| − | + | [[File:Graham Greene grave in Corseaux.JPG|thumb|400px|Graham Greene's grave in Corseaux]] | |

| + | Greene's affairs over the years were depicted in several novels, and in 1966, he had made a move to [[Antibes]]. His purpose was to be close to [[Yvonne Cloetta]], a woman whom he had known for many years. This relationship, unlike many others, endured his travels and continued until his death. Nearing the end of his life, Greene moved to the small Swiss town of Vevey, on [[Lake Geneva]]. Even though he confessed to still being a [[Catholic]], he had not practiced the religion since the 1950s. Towards the end of his life he made a point of attending Mass and honoring the sacraments. | ||

| − | + | On April 3, 1991, Graham Greene died of [[leukemia]] and was buried in Corseaux cemetery in the canton of Vaud, [[Switzerland]]. He was 86 years old. | |

| − | + | In October 2004, a third volume of his life was published by Norman Sherry, ''The Life of Graham Greene''. Sherry followed Greene's footsteps, traveling to the same countries, and even contracting several of the same diseases that Greene had been afflicted with. Sherry discovered that Greene had continued to submit reports to British intelligence until the end of his life. This led scholars and Greene's literary audience to entertain the provocative and necessary question: "Was Greene a novelist who was also a spy, or was his lifelong literary career the perfect cover?" | |

| − | == | + | == Legacy == |

| − | Greene | + | Greene is regarded as a major twentieth-century [[novelist]], and was praised by [[John Irving]], prior to Greene's death, as "the most accomplished living novelist in the English language".<ref name=Irving>John Irving, ''The Imaginary Girlfriend: A Memoir'' (Ballantine Books, 2002, ISBN 978-0345458261).</ref> Novelist [[Frederick Buechner]] called Greene's novel ''[[The Power and the Glory]]'' a "tremendous influence."<ref>Brown W. Dale, ''Of Fiction and Faith: Twelve American Writers Talk About Their Vision and Work'' (Wm. B. Eerdmans-Lightning Source, 1997, ISBN 978-0802843135).</ref> By 1943, Greene had acquired the reputation of being the "leading English male novelist of his generation,"<ref>Brian Diemert, ''Graham Greene's Thrillers and the 1930s'' (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0773514331).</ref> and at the time of his death in 1991 had a reputation as a writer of both deeply serious novels on the theme of [[Catholicism]],<ref>Ian Thomson, [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2004/oct/03/biography.grahamgreene More Sherry trifles] ''The Observer'', October 2, 2004. Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> and of "suspense-filled stories of detection."<ref>Lynette Kohn, ''Graham Greene: The Major Novels'' (Stanford University Press, 1961).</ref> Acclaimed during his lifetime, he was shortlisted for the [[Nobel Prize for Literature]]. In 1967, Greene was among the final three choices, according to Nobel records unsealed on the 50th anniversary in 2017. The committee also considered [[Jorge Luis Borges]] and [[Miguel Ángel Asturias]], with the latter the chosen winner.<ref>Alison Flood, [https://www.theguardian.com/books/2018/jan/08/nobel-archives-show-graham-greene-might-have-won-1967-prize Nobel archives show Graham Greene might have won 1967 prize] ''The Guardian'', January 8, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> |

| − | Greene' | + | Greene collected several literary awards for his novels, including the 1941 [[Hawthornden Prize]] for ''[[The Power and the Glory]]'' and the 1948 [[James Tait Black Memorial Prize]] for ''[[The Heart of the Matter]]''. As an author, he received the 1968 [[Shakespeare Prize]] and the 1981 [[Jerusalem Prize]], a biennial literary award given to writers whose works have dealt with themes of human freedom in society. In 1986, he was awarded Britain's [[Order of Merit]]. |

| − | + | The Graham Greene International Festival is an annual four-day event of conference papers, informal talks, question and answer sessions, films, dramatized readings, music, creative writing workshops and social events. It is organized by the Graham Greene Birthplace Trust, and takes place in the writer's home town of Berkhamsted (about 35 miles northwest of London), on dates as close as possible to the anniversary of his birth (2 October). Its purpose is to promote interest in and study of the works of Graham Greene.<ref>[https://grahamgreenebt.org/ Graham Greene Birthplace Trust] Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | Greene | ||

| − | + | He is the subject of the 2013 documentary film, ''[[Dangerous Edge: A Life of Graham Greene]]''.<ref>[https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2334796/ Dangerous Edge: A Life of Graham Greene (2013)] ''IMDb''. Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | + | His short story "[[The Destructors]]" was featured in the 2001 film ''[[Donnie Darko]]''.<ref>[https://spinalliterature.wordpress.com/2013/04/10/donnie-darko-and-the-destructors/ Donnie Darko and The Destructors] ''Literature of the Spine''. Retrieved July 23, 2022.</ref> | |

| − | == | + | ==Major works== |

===Verse=== | ===Verse=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''Babbling April'' (1925) |

===Novels=== | ===Novels=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''The Man Within'' (1929) ISBN 0140185305 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Name of Action'' (1930) (repudiated by author, never re-published) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Rumour at Nightfall'' (1932) (repudiated by author, never re-published) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Stamboul Train'' (1932) (also published as ''Orient Express'') ISBN 0140185321 |

| − | *'' | + | *''It's a Battlefield'' (1934) ISBN 0140185410 |

| − | *'' | + | *''England Made Me'' (1935) ISBN 0140185518 |

| − | *'' | + | *''A Gun for Sale'' (1936) (also published as ''This Gun for Hire'') ISBN 014303930X |

| − | *'' | + | *''Brighton Rock'' (1938) ISBN 0142437972 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Confidential Agent'' (1939) ISBN 0140185380 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Power and the Glory'' (1940) (also published as ''The Labyrinthine Ways'') ISBN 0142437301 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Ministry of Fear'' (1943) ISBN 0143039113 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Heart of the Matter'' (1948) ISBN 0140283323 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Third Man'' (1949) (novella, as a basis for the screenplay} ISBN 0140286829 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The End of the Affair'' (1951) ISBN 0099478447 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Quiet American'' (1955) ISBN 0143039024 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Loser Takes All'' (1955) ISBN 0140185429 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Our Man in Havana'' (1958) ISBN 0140184937 |

| − | *'' | + | *''A Burnt-Out Case'' (1960) ISBN 0140185399 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Comedians'' (1966) ISBN 0143039199 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Travels with My Aunt'' (1969) ISBN 0143039008 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Honorary Consul'' (1973) ISBN 0684871254 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Human Factor'' (1978) ISBN 0679409920 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Doctor Fischer of Geneva'' (The Bomb Party) (1980) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Monsignor Quixote'' (1982) ISBN 0671474707 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Tenth Man'' (1985) ISBN 0671019090 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Captain and the Enemy'' (1988) ISBN 014018855X |

===Autobiography=== | ===Autobiography=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''A Sort of Life'' (1971) (autobiography) ISBN 0671210106 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Ways of Escape'' (1980) (autobiography) ISBN 0671412191 |

| − | *'' | + | *''A World of My Own'' (1992) (dream diary, posthumously published) ISBN 0670852791 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Getting to Know the General'' (1984) (A Story of An Involvement) ISBN 0671541609 |

===Travel books=== | ===Travel books=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''Journey Without Maps'' (1936) ISBN 0140185798 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Lawless Roads'' (1939) ISBN 0140185801 |

| − | *'' | + | *''In Search of a Character: Two African Journals'' (1961) ISBN 014018578X |

===Plays=== | ===Plays=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''The Living Room'' (1953) ISBN 067043549X |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Potting Shed'' (1957) ISBN 0670000949 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Complaisant Lover'' (1959) ISBN 0670233730 |

| − | *'' | + | *''Carving a Statue'' (1964) ISBN 0370003365 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Return of A.J.Raffles'' (1975) ISBN 0317039423 |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Great Jowett'' (1981) ISBN 037030439X |

| − | *'' | + | *''Yes and No'' (1983) |

| − | *'' | + | *''For Whom the Bell Chimes'' (1983) ISBN 037030988X |

===Screenplays=== | ===Screenplays=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''The Future's in the Air'' (1937) |

| − | *'' | + | *''The New Britain'' (1940) |

| − | *'' | + | *''21 Days'' (1940) (based on the novel ''The First and The Last'' by [[John Galsworthy]]) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Brighton Rock'' (1947) |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Fallen Idol'' (1948) |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Third Man'' (1949) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Loser Takes All'' (1956) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Saint Joan'' (1957) (based on the play by [[George Bernard Shaw]]) |

| − | *'' | + | *''Our Man in Havana'' (1959) |

| − | *'' | + | *''The Comedians'' (1967) |

===Short stories (selected)=== | ===Short stories (selected)=== | ||

| − | *'' | + | *''Twenty-One Stories'' (1954) (originally "Nineteen Stories" [1947], the collection usually presents the stories in reverse chronological order) ISBN 0140185348 |

| − | :" | + | :"The End of the Party" (1929) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Second Death" (1929) |

| − | :" | + | :"Proof Positive" (1930) |

| − | :" | + | :"I Spy" (1930) |

| − | :" | + | :"A Day Saved" (1935) |

| − | :" | + | :"Jubilee" (1936) |

| − | :" | + | :"Brother" (1936) |

| − | :" | + | :"A Chance For Mr Lever" (1936) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Basement Room" (1936) (aka "The Fallen Idol," later turned into a film directed by [[Carol Reed]]) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Innocent" (1937) |

| − | :" | + | :"A Drive in the Country" (1937) |

| − | :" | + | :"Across The Bridge" (1938) |

| − | :" | + | :"A Little Place Off The Edgeware Road" (1939) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Case for the Defence" (1939) |

| − | :" | + | :"Alas, Poor Maling" (1940) |

| − | :" | + | :"Men At Work" (1940) |

| − | :" | + | :"Greek Meets Greek" (1941) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Hint of an Explanation" (1948) |

| − | :'' | + | :''The Third Man'' (1949) ISBN 0140286829 |

| − | :" | + | :"The Blue Film" (1954) |

| − | :" | + | :"Special Duties" (1954) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Destructors" (1954) |

* ''A Sense of Reality'' (1963) | * ''A Sense of Reality'' (1963) | ||

| − | :" | + | :"Under the Garden" |

| − | :" | + | :"A Visit to Morin" |

| − | :" | + | :"Dream of a Strange Land" |

| − | :" | + | :"A Discovery in the Woods" |

| − | :" | + | :"Church Militant" (1956) |

| − | :" | + | :"Dear Dr Falkenheim" (1963) |

| − | :" | + | :"The Blessing" (1966) |

| − | * ''May We Borrow Your Husband?'' (1967) | + | * ''May We Borrow Your Husband?'' (1967) ISBN 0140185372 |

| − | :" | + | :"May We Borrow Your Husband?" |

| − | :" | + | :"Beauty" |

| − | :" | + | :"Chagrin in Three Parts" |

| − | :" | + | :"The Over-night Bag" |

| − | :" | + | :"Mortmain" |

| − | :" | + | :"Cheap in August" |

| − | :" | + | :"A Shocking Accident" |

| − | :" | + | :"The Invisible Japanese Gentlemen" |

| − | :" | + | :"Awful When You Think of It" |

| − | :" | + | :"Doctor Crombie" |

:"The Root of All Evil" | :"The Root of All Evil" | ||

| − | :" | + | :"Two Gentle People" |

| − | * ''The Last Word and Other Stories'' (1990) | + | * ''The Last Word and Other Stories'' (1990) ISBN 0141181575 |

| − | :" | + | :"The Last Word" |

| − | :" | + | :"The News in English" |

| − | :" | + | :"The Moment of Truth" |

| − | :" | + | :"The Man Who Stole the Eiffel Tower" |

| − | :" | + | :"The Lieutenant Died Last" |

| − | :" | + | :"A Branch of the Service" |

| − | :" | + | :"An Old Man's Memory" |

| − | :" | + | :"The Lottery Ticket" |

| − | :" | + | :"The New House" |

| − | :" | + | :"Work Not in Progress" |

| − | :" | + | :"Murder for the Wrong Reason" |

| − | :" | + | :"An Appointment With the General" |

===Children's books=== | ===Children's books=== | ||

| − | *''The Little Fire Engine'' (n.d., illus. [[Dorothy Craigie]]; 1973, illus. [[Edward Ardizzone]]) | + | *''The Little Fire Engine'' (n.d., illus. [[Dorothy Craigie]]; 1973, illus. [[Edward Ardizzone]]) ISBN 0370020219 |

| − | *''The Little Horse Bus'' (1966, illus. Dorothy Craigie) | + | *''The Little Horse Bus'' (1966, illus. Dorothy Craigie) ISBN 038509826X |

| − | *''The Little Steamroller'' (1963, illus. Dorothy Craigie) | + | *''The Little Steamroller'' (1963, illus. Dorothy Craigie) ISBN 0385089171 |

| − | *''The Little Train'' (1957, illus. Dorothy Craigie; 1973, illus. Edward Ardizzone) | + | *''The Little Train'' (1957, illus. Dorothy Craigie; 1973, illus. Edward Ardizzone) ISBN 0370020200 |

===Other=== | ===Other=== | ||

| − | *''An | + | *''An Impossible Woman: The Memories of Dottoressa Moor of Capri'' (ed. Greene, 1975) |

| − | *Introduction to ''My Silent War'', by [[Kim Philby]], 1968, British Intelligence | + | *Introduction to ''My Silent War'', by [[Kim Philby]], 1968, British Intelligence double agent, mole for Soviets ISBN 0375759832 |

| − | * ''J' | + | * ''J'Accuse—The Dark Side of Nice'' (1982) |

| − | *''Lord Rochester's | + | *''Lord Rochester's Monkey: Being the life of John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester'' (1974) ISBN 0140041974 |

| − | *''The Pleasure-Dome: The Collected Film Criticism, | + | *''The Pleasure-Dome: The Collected Film Criticism, 1935–40'' (ed. John Russell Taylor, 1980) ISBN 0436187981 |

*''The Old School: Essays by Divers Hands'' (ed. Greene, 1974) | *''The Old School: Essays by Divers Hands'' (ed. Greene, 1974) | ||

*''Yours, etc.: Letters to the Press'' (1989) | *''Yours, etc.: Letters to the Press'' (1989) | ||

*''Why the Epigraph?'' (1989) | *''Why the Epigraph?'' (1989) | ||

| − | == | + | ==Notes== |

| − | * | + | <references/> |

| − | * | + | |

| − | * | + | ==References== |

| − | * | + | * Dale, Brown W. ''Of Fiction and Faith: Twelve American Writers Talk About Their Vision and Work''. Wm. B. Eerdmans-Lightning Source, 1997. ISBN 978-0802843135 |

| − | * | + | * Diemert, Brian. ''Graham Greene's Thrillers and the 1930s''. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0773514331 |

| − | * | + | * Duran, Leopoldo. ''Graham Greene: Friend and Brother.'' translated by Euan Cameron. HarperCollins, 1994. ISBN 978-0006276609 |

| − | * | + | * Irving, John. ''The Imaginary Girlfriend: A Memoir''. Ballantine Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0345458261 |

| − | * | + | * Kelly, Richard M. ''Graham Greene.'' Ungar, 1985. ISBN 0804424640 |

| − | + | * Kelly, Richard M. ''Graham Greene: A Study of the Short Fiction.'' Twayne, 1992. ISBN 978-0805783421 | |

| + | * Kohn, Lynette. ''Graham Greene: The Major Novels''. Stanford University Press, 1961. | ||

| + | * O'Prey, Paul. ''A Reader's Guide to Graham Greene.'' Thames and Hudson, 1988. ISBN 0500150192 | ||

| + | * Shelden, Michael. ''Graham Greene: The Enemy Within.'' William Heinemann, 1994. ISBN 0679428836 | ||

| + | * Sherry, Norman. ''The Life of Graham Greene: vol. 1 1904-1939.'' Random House UK, 1989. ISBN 0224026542 | ||

| + | * Sherry, Norman. ''The Life of Graham Greene: vol. 2 1939-1955.'' Viking, 1994. ISBN 0670860565 | ||

| + | * Sherry, Norman. ''The Life of Graham Greene: vol. 3 1955-1991.'' Viking, 2004. ISBN 0670031429 | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| − | + | All links retrieved July 23, 2022. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | *[ | + | *[https://greeneland.tripod.com/ Greeneland: the world of Graham Greene]. |

| − | + | *[https://www.litencyc.com/php/speople.php?rec=true&UID=1864 Graham Greene] ''The Literary Encyclopedia''. | |

| − | *[ | + | *[http://www.scena.org/columns/lebrecht/040524-NL-twowriters.html A Tale of Two Writers]. |

| − | *[http://www. | + | *[https://www.imdb.com/name/nm0001294/ Graham Greene] ''IMDb''. |

| − | |||

| − | *[ | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Writers and poets]] |

| − | [[Category: | + | [[Category:Actors and playwrights]] |

| − | |||

{{Credit|82572597}} | {{Credit|82572597}} | ||

Latest revision as of 10:04, 31 December 2022

Henry Graham Greene, OM, CH (October 2, 1904 – April 3, 1991), was a visionary English novelist, playwright, short story writer, and critic. He also penned several screenplays for Hollywood, and in turn, many of his works, which are full of action and suspense, have been made into films. Greene's stylistic work is known for its explorations of moral issues dealt with in a political setting. His novels gained him a reputation as one of the most widely read writers of the twentieth century.

Graham Greene, known as a world-traveler, would often seek out adventure to fuel his stories and experience the political world of various nations up close. Many of his writings are centered on the religious beliefs of Roman Catholicism, although he detested being described as a "Catholic novelist" rather than as a "novelist who happened to be Catholic." His focus on religion did not deter readers or jade Greene's writings, but on the contrary, in novels such as Brighton Rock, The Heart of the Matter, The End of the Affair, Monsignor Quixote, and his famous work The Power and the Glory, it only made them more poignant. His intense focus on moral issues, politics, and religion, mixed with suspense and adventure, became the trademark of Graham Greene's ingenious works.

Life and work

Childhood

Graham Greene was the fourth born child to Charles Henry and Marion Raymond Greene. Greene was raised in Berkhamsted, Hertfordshire, and was a very shy and sensitive child. Graham was born into a large and influential family. His parents were first cousins, and were related to the writer Robert Louis Stevenson. His father was related to the owners of the large and influential Greene King brewery. The more distant relations of the family were comprised of various bankers, barristers, and businessmen.

Graham's siblings also made significant individual marks on the world. Greene's younger brother, Hugh served as the Director-General of the British Broadcasting Company (BBC), and his older brother, Raymond, was an eminent doctor and mountaineer, involved in both the 1931 Kamet and 1933 Everest expeditions.

In 1910, Charles Greene succeeded Dr. Thomas Fry as headmaster at Berkhamsted School, and Graham, along with his brothers, began attending Berkhamsted. Greene's years as a student at the school were full of profound unhappiness. Graham was constantly bullied, beat-up, mocked, and made fun of. He often skipped classes to find solitude in reading. His escapes only garnered him censure from his father, and he found that he could not balance the torrid treatment by his peers and the stern treatment by his father. During the three years at Berkhamsted, it is reported that Greene attempted suicide on several different occasions. Greene claimed that often he would sit and play Russian roulette—but Michael Shelden's biography of the author discredits this claim.

One day, Greene simply left school, leaving a letter for his parents that said he would not return. This led his parents sending him to a therapist in London to deal with his depression. Greene was seventeen at the time. His therapist, Kenneth Richmond, encouraged Greene to write and even introduced Greene to a few of his literary friends, like Walter de la Mare.

Greene returned to finish his high school education at Berkhamsted. He continued on at Balliol College, Oxford, where he published more than sixty stories, articles, reviews, and poems in the student magazine, Oxford Outlook. He reached a milestone in his life when his first volume of poetry was published in 1925, while he was still an undergraduate. In 1926, Graham Greene converted to Roman Catholicism, later stating that "I had to find a religion… to measure my evil against."

Early career

In 1926, Greene graduated and began a career in journalism. His first post was in Nottingham, a city he depicted in several of his novels, and while working he received a letter from Vivien Dayrell-Browning, also a Catholic, who had written to Greene and corrected him on points of Catholic doctrine. Greene was intrigued and they began a correspondence. Greene moved to London that same year and began working as an editor of The Times as well as The Spectator, where he was employed as a film critic and a literary editor until 1940.

In 1927, Greene and Vivien were married, although, Greene is the first to admit that he was not a family man and reportedly disliked children. Greene was unfaithful to Vivien and the marriage fell apart in 1948. Despite his feelings about children, the couple had two, Lucy (1933) and Francis (1936). Throughout his marriage, Greene had a number of affairs with various women. Often his mistresses were married women who lived in different countries. In 1948, Greene left Vivien for Catherine Walston, even though the couple never officially filed for divorce.

Novels and other works

Graham Greene published his first novel in 1929, and with the publication of The Man Within, he began devoting all his time to writing. Greene quit his full-time post and supplemented his income with freelance jobs. Along with working for The Spectator, he also co-edited the magazine, Night and Day. In 1937, the magazine closed down after Greene wrote a review of Wee Willie Winkie, a film starring Shirley Temple. In the review, Greene wrote that Temple displayed "a certain adroit coquetry which appealed to middle-aged men." This comment caused the magazine to lose a libel case, and it remains the first criticism in the entertainment industry of the sexualization of children.

His first real success came with the publication of Stamboul Train in 1932 (adapted into the film, Orient Express, in 1934). He met with other success as he continued to write, often having two very distinct audiences. There was the audience that loved Greene's thrillers and suspense novels like Brighton Rock and there was a completely different audience who admired Greene's genius in literary novels such as The Power and the Glory. Considered the best novel of his career, it was both acclaimed (Hawthornden Prize winner in 1941) and condemned (by the Vatican). While Greene was able to divide his works into two genres, his reputation as a literary writer gained him more recognition.

Greene's diverse talent was recognized when his mystery/suspense novels began to be valued as much as his more serious novels. Such works as The Human Factor, The Comedians, Our Man in Havana, and The Quiet American showed Greene's ability to create an entertaining and thrilling story and combine it with serious insight, depth of character, and universal themes.

With the success of his books, Greene expanded his literary repertoire to short stories and plays. He also wrote many screenplays, his most famous one being The Third Man. In addition, several of his books were made into films, including 1947's Brighton Rock and The Quiet American(2002), set in Vietnam and starring Michael Caine (for which Caine was nominated for an Oscar).

Greene was considered for the Nobel Prize for Literature several times, but he never received the prize. Some attributed this to the very fact that he was so popular, as the scholarly elite disliked this trait. His religious themes were also thought to have played a role in whether or not he was awarded the honor, as it might have alienated some of the judges.

Writing style and themes

Greene's writings were innovative, not only in the religious themes he incorporated, but also in his avoidance of popular modernist experiments. His writings were characterized by a straightforward and clear manner. He was a realist, yet his technique created suspenseful and exciting plots. His word combinations led many to feel like they were reading something cinematic. His descriptions were full of imagery, yet he was not superfluous in his word usage, a trait that was admired by his audience and contributed to his wide popularity.

Another facet of Greene's writing style was the ability he had to depict the internal struggles that his characters faced, as well as their outward struggles. His characters were deeply spiritual with emotional depth and intelligence. They each faced universal struggles, but Greene portrayed them as highly individualistic. The reader cares deeply for the characters facing rampant cynicism and world-weariness. His characters often faced living conditions that were harsh, wretched and squalid. The settings of Greene's stories were poverty stricken countries like Mexico, West Africa, Vietnam, Haiti, Argentina—countries that were hot, humid, and abject. This trait led to the coining of the expression "Greeneland" for describing such settings.

Even with the most destitute of circumstances Greene's characters had the values and beliefs of Catholicism explicitly present in their lives. Greene was critical of the literature of his time for its dull, superficial characters who "wandered about like cardboard symbols through a world that is paper-thin." He felt that literature could be saved by adding religious elements to the stories. He felt the basic struggle between good and evil, the basic beliefs in right and wrong, the realities of sin and grace, were all tools to be used in creating a more sensitive and spiritual character. Greene believed that the consequences of evil were just as real as the benefits of being good. V. S. Pritchett praised Greene, saying that he was the first English novelist since Henry James to present, and grapple with, the reality of evil.[1] This ever present portrayal of evil was scorned by the leading theologian of the day, Hans Urs von Balthasar, who said the Greene had given sin a certain "mystique." Greene not only dealt with the opposites of sin and virtue, but he explored many other Christian aspects of life as well, such as the value of faith, peace, and joy. Greene received both praise and criticism from Catholic writers and scholars.

As Greene grew older, his writings changed. No longer did he focus as intently on religious views. Instead, his focus became more wide-spread and approachable to a broader audience. He turned to a more "humanistic" viewpoint. In addition to this, he outwardly rejected many of the orthodox Catholic teachings he had embraced earlier in his life. Readers of his work began to see that the protagonists were much more likely to be believers in Communism rather than Catholicism.

Greene's political views were different from other "Catholic writers" of the time, like Evelyn Waugh and Anthony Burgess. While they maintained a strictly right-winged agenda, Greene was always leaning left, and his travels influenced these ideas. Though many claim that politics did not interest Greene, his novels all began to reflect on and criticize American imperialism. Greene became a sympathizer with those who opposed the American government, like the Cuban leader Fidel Castro.[2]

Travel

During World War II, Greene began to travel extensively; this travel would play a major part in the rest of his life. In fact, it was his travels and the people he met in various countries that inspired many of his plots, themes, and characters. In 1938, for example, the Roman Catholic Church funded Greene's trip to Mexico. The purpose of this trip was for Greene to observe and write about the effects of a forced anti-Catholic campaign against secularization. This event led to Greene writing The Lawless Roads (or Another Mexico, as it was known in America) and it formed the core of the fictional novel, The Power and the Glory.

During World War II, a notorious double agent, Kim Philby recruited Greene to work for England's own MI6. This stint in espionage fueled Greene's desire to travel, as well as provided him with memorable and intriguing characters. Greene became obsessed with traveling to the "wild and remote" places of the world. His travels led him to François Duvalier's Haiti, where he set his 1966 novel, The Comedians. Greene became so well-known in Haiti that the proprietor of the Hotel Oloffson in Port-au-Prince, named a room in the hotel in honor of Greene. After the war ended, he continued to travel as a free-lance journalist. He spent a long period on the French Riviera, in particular, Nice. He also made several anti-American comments during his travels, thus opening doors to Communist leaders like Fidel Castro and Ho Chi Minh, whom he interviewed. Greene's close friend, Evelyn Waugh, wrote a letter in support of Greene as "a secret agent on our side and all his buttering up of the Russians is 'cover'."

There is so much weariness and disappointment in travel that people have to open up—in railway trains, over a fire, on the decks of steamers, and in the palm courts of hotels on a rainy day. They have to pass the time somehow, and they can pass it only with themselves. Like the characters of Anton Chekhov they have no reserves—you learn the most intimate secrets. You get an impression of a world peopled by eccentrics, of odd professions, almost incredible stupidities, and, to balance them, amazing endurances (Graham Greene, The Lawless Roads, 1939).

Final years and death

Greene published two volumes of his autobiography, A Sort of Life in 1971, and Ways of Escape in 1980.

In, J'Accuse—The Dark Side of Nice (1982), one of his last works, he wrote about the travesties he saw while living in Nice. He wrote specifically about the organized crime that corrupted the very foundations of the civic government and the severe judicial and police corruption abounding in the society. His writings were not ignored, and this led to a libel case, which he lost. Vindication came in 1994, three years after his death, when the former mayor of Nice, Jacques Médecin, was finally convicted and sentenced to jail for several counts of corrupt behavior and criminal actions.

Greene's affairs over the years were depicted in several novels, and in 1966, he had made a move to Antibes. His purpose was to be close to Yvonne Cloetta, a woman whom he had known for many years. This relationship, unlike many others, endured his travels and continued until his death. Nearing the end of his life, Greene moved to the small Swiss town of Vevey, on Lake Geneva. Even though he confessed to still being a Catholic, he had not practiced the religion since the 1950s. Towards the end of his life he made a point of attending Mass and honoring the sacraments.

On April 3, 1991, Graham Greene died of leukemia and was buried in Corseaux cemetery in the canton of Vaud, Switzerland. He was 86 years old.

In October 2004, a third volume of his life was published by Norman Sherry, The Life of Graham Greene. Sherry followed Greene's footsteps, traveling to the same countries, and even contracting several of the same diseases that Greene had been afflicted with. Sherry discovered that Greene had continued to submit reports to British intelligence until the end of his life. This led scholars and Greene's literary audience to entertain the provocative and necessary question: "Was Greene a novelist who was also a spy, or was his lifelong literary career the perfect cover?"

Legacy

Greene is regarded as a major twentieth-century novelist, and was praised by John Irving, prior to Greene's death, as "the most accomplished living novelist in the English language".[3] Novelist Frederick Buechner called Greene's novel The Power and the Glory a "tremendous influence."[4] By 1943, Greene had acquired the reputation of being the "leading English male novelist of his generation,"[5] and at the time of his death in 1991 had a reputation as a writer of both deeply serious novels on the theme of Catholicism,[6] and of "suspense-filled stories of detection."[7] Acclaimed during his lifetime, he was shortlisted for the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1967, Greene was among the final three choices, according to Nobel records unsealed on the 50th anniversary in 2017. The committee also considered Jorge Luis Borges and Miguel Ángel Asturias, with the latter the chosen winner.[8]

Greene collected several literary awards for his novels, including the 1941 Hawthornden Prize for The Power and the Glory and the 1948 James Tait Black Memorial Prize for The Heart of the Matter. As an author, he received the 1968 Shakespeare Prize and the 1981 Jerusalem Prize, a biennial literary award given to writers whose works have dealt with themes of human freedom in society. In 1986, he was awarded Britain's Order of Merit.

The Graham Greene International Festival is an annual four-day event of conference papers, informal talks, question and answer sessions, films, dramatized readings, music, creative writing workshops and social events. It is organized by the Graham Greene Birthplace Trust, and takes place in the writer's home town of Berkhamsted (about 35 miles northwest of London), on dates as close as possible to the anniversary of his birth (2 October). Its purpose is to promote interest in and study of the works of Graham Greene.[9]

He is the subject of the 2013 documentary film, Dangerous Edge: A Life of Graham Greene.[10]

His short story "The Destructors" was featured in the 2001 film Donnie Darko.[11]

Major works

Verse

- Babbling April (1925)

Novels

- The Man Within (1929) ISBN 0140185305

- The Name of Action (1930) (repudiated by author, never re-published)

- Rumour at Nightfall (1932) (repudiated by author, never re-published)

- Stamboul Train (1932) (also published as Orient Express) ISBN 0140185321

- It's a Battlefield (1934) ISBN 0140185410

- England Made Me (1935) ISBN 0140185518

- A Gun for Sale (1936) (also published as This Gun for Hire) ISBN 014303930X

- Brighton Rock (1938) ISBN 0142437972

- The Confidential Agent (1939) ISBN 0140185380

- The Power and the Glory (1940) (also published as The Labyrinthine Ways) ISBN 0142437301

- The Ministry of Fear (1943) ISBN 0143039113

- The Heart of the Matter (1948) ISBN 0140283323

- The Third Man (1949) (novella, as a basis for the screenplay} ISBN 0140286829

- The End of the Affair (1951) ISBN 0099478447

- The Quiet American (1955) ISBN 0143039024

- Loser Takes All (1955) ISBN 0140185429

- Our Man in Havana (1958) ISBN 0140184937

- A Burnt-Out Case (1960) ISBN 0140185399

- The Comedians (1966) ISBN 0143039199

- Travels with My Aunt (1969) ISBN 0143039008

- The Honorary Consul (1973) ISBN 0684871254

- The Human Factor (1978) ISBN 0679409920

- Doctor Fischer of Geneva (The Bomb Party) (1980)

- Monsignor Quixote (1982) ISBN 0671474707

- The Tenth Man (1985) ISBN 0671019090

- The Captain and the Enemy (1988) ISBN 014018855X

Autobiography

- A Sort of Life (1971) (autobiography) ISBN 0671210106

- Ways of Escape (1980) (autobiography) ISBN 0671412191

- A World of My Own (1992) (dream diary, posthumously published) ISBN 0670852791

- Getting to Know the General (1984) (A Story of An Involvement) ISBN 0671541609

Travel books

- Journey Without Maps (1936) ISBN 0140185798

- The Lawless Roads (1939) ISBN 0140185801

- In Search of a Character: Two African Journals (1961) ISBN 014018578X

Plays

- The Living Room (1953) ISBN 067043549X

- The Potting Shed (1957) ISBN 0670000949

- The Complaisant Lover (1959) ISBN 0670233730

- Carving a Statue (1964) ISBN 0370003365

- The Return of A.J.Raffles (1975) ISBN 0317039423

- The Great Jowett (1981) ISBN 037030439X

- Yes and No (1983)

- For Whom the Bell Chimes (1983) ISBN 037030988X

Screenplays

- The Future's in the Air (1937)

- The New Britain (1940)

- 21 Days (1940) (based on the novel The First and The Last by John Galsworthy)

- Brighton Rock (1947)

- The Fallen Idol (1948)

- The Third Man (1949)

- Loser Takes All (1956)

- Saint Joan (1957) (based on the play by George Bernard Shaw)

- Our Man in Havana (1959)

- The Comedians (1967)

Short stories (selected)

- Twenty-One Stories (1954) (originally "Nineteen Stories" [1947], the collection usually presents the stories in reverse chronological order) ISBN 0140185348

- "The End of the Party" (1929)

- "The Second Death" (1929)

- "Proof Positive" (1930)

- "I Spy" (1930)

- "A Day Saved" (1935)

- "Jubilee" (1936)

- "Brother" (1936)

- "A Chance For Mr Lever" (1936)

- "The Basement Room" (1936) (aka "The Fallen Idol," later turned into a film directed by Carol Reed)

- "The Innocent" (1937)

- "A Drive in the Country" (1937)

- "Across The Bridge" (1938)

- "A Little Place Off The Edgeware Road" (1939)

- "The Case for the Defence" (1939)

- "Alas, Poor Maling" (1940)

- "Men At Work" (1940)

- "Greek Meets Greek" (1941)

- "The Hint of an Explanation" (1948)

- The Third Man (1949) ISBN 0140286829

- "The Blue Film" (1954)

- "Special Duties" (1954)

- "The Destructors" (1954)

- A Sense of Reality (1963)

- "Under the Garden"

- "A Visit to Morin"

- "Dream of a Strange Land"

- "A Discovery in the Woods"

- "Church Militant" (1956)

- "Dear Dr Falkenheim" (1963)

- "The Blessing" (1966)

- May We Borrow Your Husband? (1967) ISBN 0140185372

- "May We Borrow Your Husband?"

- "Beauty"

- "Chagrin in Three Parts"

- "The Over-night Bag"

- "Mortmain"

- "Cheap in August"

- "A Shocking Accident"

- "The Invisible Japanese Gentlemen"

- "Awful When You Think of It"

- "Doctor Crombie"

- "The Root of All Evil"

- "Two Gentle People"

- The Last Word and Other Stories (1990) ISBN 0141181575

- "The Last Word"

- "The News in English"

- "The Moment of Truth"

- "The Man Who Stole the Eiffel Tower"

- "The Lieutenant Died Last"

- "A Branch of the Service"

- "An Old Man's Memory"

- "The Lottery Ticket"

- "The New House"

- "Work Not in Progress"

- "Murder for the Wrong Reason"

- "An Appointment With the General"

Children's books

- The Little Fire Engine (n.d., illus. Dorothy Craigie; 1973, illus. Edward Ardizzone) ISBN 0370020219

- The Little Horse Bus (1966, illus. Dorothy Craigie) ISBN 038509826X

- The Little Steamroller (1963, illus. Dorothy Craigie) ISBN 0385089171

- The Little Train (1957, illus. Dorothy Craigie; 1973, illus. Edward Ardizzone) ISBN 0370020200

Other

- An Impossible Woman: The Memories of Dottoressa Moor of Capri (ed. Greene, 1975)

- Introduction to My Silent War, by Kim Philby, 1968, British Intelligence double agent, mole for Soviets ISBN 0375759832

- J'Accuse—The Dark Side of Nice (1982)

- Lord Rochester's Monkey: Being the life of John Wilmot, Second Earl of Rochester (1974) ISBN 0140041974

- The Pleasure-Dome: The Collected Film Criticism, 1935–40 (ed. John Russell Taylor, 1980) ISBN 0436187981

- The Old School: Essays by Divers Hands (ed. Greene, 1974)

- Yours, etc.: Letters to the Press (1989)

- Why the Epigraph? (1989)

Notes

- ↑ Edward Short, The Catholic Novels of Graham Greene Crisis Magazine, April 1, 2005. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ Tom Miller, Sex, Spies and Literature The Washington Post, April 14, 1991. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ John Irving, The Imaginary Girlfriend: A Memoir (Ballantine Books, 2002, ISBN 978-0345458261).

- ↑ Brown W. Dale, Of Fiction and Faith: Twelve American Writers Talk About Their Vision and Work (Wm. B. Eerdmans-Lightning Source, 1997, ISBN 978-0802843135).

- ↑ Brian Diemert, Graham Greene's Thrillers and the 1930s (McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0773514331).

- ↑ Ian Thomson, More Sherry trifles The Observer, October 2, 2004. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ Lynette Kohn, Graham Greene: The Major Novels (Stanford University Press, 1961).

- ↑ Alison Flood, Nobel archives show Graham Greene might have won 1967 prize The Guardian, January 8, 2018. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ Graham Greene Birthplace Trust Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ Dangerous Edge: A Life of Graham Greene (2013) IMDb. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

- ↑ Donnie Darko and The Destructors Literature of the Spine. Retrieved July 23, 2022.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dale, Brown W. Of Fiction and Faith: Twelve American Writers Talk About Their Vision and Work. Wm. B. Eerdmans-Lightning Source, 1997. ISBN 978-0802843135

- Diemert, Brian. Graham Greene's Thrillers and the 1930s. McGill-Queen's University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0773514331

- Duran, Leopoldo. Graham Greene: Friend and Brother. translated by Euan Cameron. HarperCollins, 1994. ISBN 978-0006276609

- Irving, John. The Imaginary Girlfriend: A Memoir. Ballantine Books, 2002. ISBN 978-0345458261

- Kelly, Richard M. Graham Greene. Ungar, 1985. ISBN 0804424640

- Kelly, Richard M. Graham Greene: A Study of the Short Fiction. Twayne, 1992. ISBN 978-0805783421

- Kohn, Lynette. Graham Greene: The Major Novels. Stanford University Press, 1961.

- O'Prey, Paul. A Reader's Guide to Graham Greene. Thames and Hudson, 1988. ISBN 0500150192

- Shelden, Michael. Graham Greene: The Enemy Within. William Heinemann, 1994. ISBN 0679428836

- Sherry, Norman. The Life of Graham Greene: vol. 1 1904-1939. Random House UK, 1989. ISBN 0224026542

- Sherry, Norman. The Life of Graham Greene: vol. 2 1939-1955. Viking, 1994. ISBN 0670860565

- Sherry, Norman. The Life of Graham Greene: vol. 3 1955-1991. Viking, 2004. ISBN 0670031429

External links

All links retrieved July 23, 2022.

- Greeneland: the world of Graham Greene.

- Graham Greene The Literary Encyclopedia.

- A Tale of Two Writers.

- Graham Greene IMDb.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.