Continental shelf

The continental shelf is the extended perimeter of each continent and associated coastal plain, which, during interglacial periods (such as the current geological epoch), is covered by relatively shallow seas (known as shelf seas) and gulfs.

Topography

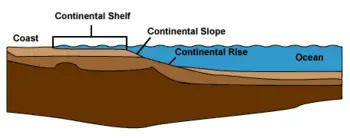

The continental shelf usually ends at a point of increasing slope (called the shelf break). The sea floor below the break is called the continental slope. Below the slope is the continental rise, which finally merges into the deep ocean floor, the abyssal plain. The continental shelf and the slope are part of the continental margin.

The shelf area is commonly subdivided into the inner continental shelf, mid-continental shelf, and outer continental shelf, each with its specific geomorphology and marine biology.

The character of the shelf changes dramatically at the shelf break, where the continental slope begins. With a few exceptions, the shelf break is located at a remarkably uniform depth of roughly 140 meters (m) (460 feet (ft)). This feature is likely a hallmark of past ice ages, when sea level was lower than what it currently is.[1]

The continental slope is much steeper than the shelf; the average angle is 3°, but it can be as low as 1° or as high as 10°.[2] The slope is often cut with submarine canyons, features whose origin was mysterious for many years.[3]

The continental rise is below the slope, but landward of the abyssal plains. Its gradient is intermediate between the slope and the shelf, on the order of 0.5-1°.[4] Extending as far as 500 kilometers (km) from the slope, it consists of thick sediments deposited by turbidity currents from the shelf and slope. Sediment cascades down the slope and accumulates as a pile of sediment at the base of the slope, called the continental rise.[5]

Geographical distribution

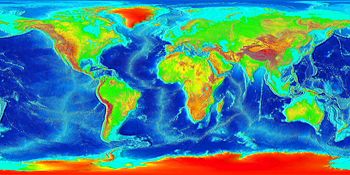

The width of the continental shelf varies considerably – it is not uncommon for an area to have virtually no shelf at all, particularly where the forward edge of an advancing oceanic plate dives beneath continental crust in an offshore subduction zone such as off the coast of Chile or the west coast of Sumatra. The largest shelf – the Siberian Shelf in the Arctic Ocean – stretches to 1500 kilometers (930 miles) in width. The South China Sea lies over another extensive area of continental shelf, the Sunda Shelf, which joins Borneo, Sumatra, and Java to the Asian mainland. Other familiar bodies of water that overlie continental shelves are the North Sea and the Persian Gulf. The average width of continental shelves is about 80 km (50 mi). The depth of the shelf also varies, but is generally limited to water shallower than 150 m (490 ft).[6] The slope of the shelf is usually quite low, on the order of 0.5°; vertical relief is also minimal, at less than 20 m (65 ft).[7]

Though the continental shelf is treated as a physiographic province of the ocean, it is not part of the deep ocean basin proper, but the flooded margins of the continent.[8] Passive continental margins, such as most of the Atlantic coasts, have wide and shallow shelves, made of thick sedimentary wedges derived from long erosion of a neighboring continent. Active continental margins have narrow, relatively steep shelves, due to frequent earthquakes that move sediment to the deep sea.[9]

Sediments

The continental shelves are covered by terrigenous sediments, that is, sediments derived from erosion of the continents. However, little of the sediment is from current rivers; some 60-70 percent of the sediment on the world's shelves is relict sediment, deposited during the last ice age, when sea level was 100-120 m lower than it is now.[10]

Sediments usually become increasingly fine with distance from the coast; sand is limited to shallow, wave-agitated waters, while silt and clays are deposited in quieter, deep water far offshore.[11] These shelf sediments accumulate at an average rate of 30 cm/1000 years, with a range from 15-40 cm.[12] Though slow by human standards, this rate is much faster than that for deep-sea pelagic sediments.

Biota

Combined with the sunlight available in shallow waters, the continental shelves teem with life compared to the biotic desert of the oceans' abyssal plain. The pelagic (water column) environment of the continental shelf constitutes the neritic zone, and the benthic (sea floor) province of the shelf is the sublittoral zone.[13]

Though the shelves are usually fertile, if anoxic conditions in the sedimentary deposits prevail, the shelves may in geologic time become sources of fossil fuels.

Economic significance

The relatively accessible continental shelf is the best understood part of the ocean floor. Most of the commercial exploitation of the sea—such as the extraction of metallic ore, nonmetallic ore, and hydrocarbons (petroleum)—takes place on the continental shelf. Sovereign rights over their continental shelves up to 350 nautical miles from the coast were claimed by the marine nations that signed the Convention on the Continental Shelf drawn up by the U.N. International Law Commission in 1958, which was partly superseded by the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.[14]

See also

- Land bridge

- Ocean

- Oceanography

- Territorial waters

Notes

- ↑ Gross 1972, p. 43.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 36; Gross 1972, p. 43.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 98; Gross 1972, p. 44.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 37.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 39; Gross 1972, p. 45.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, p. 37.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, pp. 36-37.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, pp. 90-93.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, pp. 84-86; Gross, 1972, p. 43.

- ↑ Gross 1972, pp. 121-22.

- ↑ Gross 1972, p. 127.

- ↑ Pinet 1996, pp. 316-17, 418-19.

- ↑ U.N. Convention on the Continental Shelf, 1958. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cook, Peter J., and Chris M. Carleton, eds. 2000. Continental Shelf Limits: The Scientific and Legal Interface. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195117824.

- Garrison, Tom S. 2007. Oceanography: An Invitation to Marine Science. Boston, MA: Brooks Cole. ISBN 049511913X.

- Gross, Grant M. 1972. Oceanography: A View of the Earth. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall. ISBN 0136296599.

- Pinet, Paul R. 1996. Invitation to Oceanography. 3rd ed. St. Paul, MN: West Publishing Co. ISBN 0763721360.

- Nordquist, Myron H., John Norton Moore, and Tomas H. Heidar. 2004. Legal and Scientific Aspects of Continental Shelf Limits. Center for Oceans Law and Policy, University of Virginia. Leiden: M. Nijhoff. ISBN 978-9004139121.

External links

- Ocean Regions: Ocean Floor - Continental Margin & Rise. Office of Naval Research. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

- UNEP Shelf Programme. UNEP/GRID-Arendal. Retrieved June 18, 2008.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.