Difference between revisions of "Brunhild" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m (→References) |

||

| Line 20: | Line 20: | ||

==Mythic Accounts== | ==Mythic Accounts== | ||

| − | + | ===Brynhildr in the Volsunga Saga=== | |

| + | {{main|Volsunga saga}} | ||

| + | :See also: [[Sigurd]] | ||

According to the Völungasaga, Brynhildr is the daughter of [[Budli]]. She was ordered to decide a fight between two kings: Hjalmgunnar and Agnar. The valkyrie knew that [[Odin]] himself preferred the older king, Hjalmgunnar, yet Brynhildr decided the battle for Agnar. For this [[Odin]] condemned the valkyrie to live the life of a mortal woman, and imprisoned her in a remote castle behind a wall of shields on top of mount ''Hindarfjall'' in the Alps, and cursed her to sleep until any man would rescue and marry her. The hero [[Sigurd|Sigurðr]] [[Sigmund]]son (''Siegfried'' in the Nibelungenlied), heir to the clan of [[Völsung]] and slayer of the dragon [[Fafnir]], entered the castle and awoke Brynhildr by removing her helmet and cutting off her chainmail armour. He immediately fell in love with the shieldmaiden and proposed to her with the magic ring [[Andvarinaut]]. Promising to return and make Brynhildr his bride, Sigurðr then left the castle and headed for the court of [[Gjuki]], the king of [[Burgundy]].<ref>Byock, Jesse L. ''The Saga of the Volsungs.'' London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044738-5.</ref> | According to the Völungasaga, Brynhildr is the daughter of [[Budli]]. She was ordered to decide a fight between two kings: Hjalmgunnar and Agnar. The valkyrie knew that [[Odin]] himself preferred the older king, Hjalmgunnar, yet Brynhildr decided the battle for Agnar. For this [[Odin]] condemned the valkyrie to live the life of a mortal woman, and imprisoned her in a remote castle behind a wall of shields on top of mount ''Hindarfjall'' in the Alps, and cursed her to sleep until any man would rescue and marry her. The hero [[Sigurd|Sigurðr]] [[Sigmund]]son (''Siegfried'' in the Nibelungenlied), heir to the clan of [[Völsung]] and slayer of the dragon [[Fafnir]], entered the castle and awoke Brynhildr by removing her helmet and cutting off her chainmail armour. He immediately fell in love with the shieldmaiden and proposed to her with the magic ring [[Andvarinaut]]. Promising to return and make Brynhildr his bride, Sigurðr then left the castle and headed for the court of [[Gjuki]], the king of [[Burgundy]].<ref>Byock, Jesse L. ''The Saga of the Volsungs.'' London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044738-5.</ref> | ||

Gjuki's wife, the sorceress [[Grimhild]], wanting Sigurðr married to her daughter [[Gudrun]] ([[Kriemhild]] in Nibelungenlied), prepared a magic potion that made Sigurðr forget about Brynhildr. Sigurðr soon married Gudrun. Hearing of Sigurðr's encounter with the valkyrie, Grimhild decided to make Brynhildr the wife of her son [[Gunnar]] ([[Gunther]] in the Nibelungenlied). Gunnar then sought to court Brynhild but was stopped by a ring of fire around the castle. He tried to ride through the flames with his own horse and then with Sigurðr's horse, [[Grani]], but still failed. Sigurðr then exchanged shapes with him and entered the ring of fire. Sigurðr (disguised as Gunnar) and Brynhildr married, and they stayed there three nights, but Sigurðr laid his sword between them (meaning that he did not take her virginity before giving her to the real Gunnar). Sigurðr also took the ring Andvarinaut from her finger and later gave it to Gudrun. Gunnar and Sigurðr soon returned to their true forms, with Brynhildr thinking she married Gunnar. However, Gudrun and Brynhild later quarreled over whose husband was greater, Brynhildr boasting that even Sigurðr was not brave enough to ride through the flames. Gudrun revealed that it was actually Sigurðr who rode through the ring of fire, and Brynhildr became enraged. Sigurðr, remembering the truth, tried to console her, but to no avail. Brynhildr plotted revenge by urging Gunnar to kill Sigurðr, telling him that he slept with her in Hidarfjall, which he swore not to do. Gunnar and his brother [[Hogni]] ([[Hagen]] in the [[Nibelungenlied]]) were afraid to kill him themselves, as they had sworn oaths of brotherhood to Sigurðr. They incited their younger brother, [[Gutthorm]] to kill Sigurðr, by giving him a magic potion that enraged him, and he mudered Sigurðr in his sleep. Dying, Sigurðr threw his sword at Gutthorm, killing him. <ref>Byock</ref>(some Eddic poems say Gutthorm killed him in the forest south of the [[Rhine]], also while resting)<ref>"Gudrunarkviða I" in Bellows, Henry Adams. (Trans.). (1923). ''The Poetic Edda: Translated from the Icelandic with an Introduction and Notes''. New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation. Reprinted Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellon Press. ISBN 0-88946-783-8. (Available at Sacred Texts: Sagas and Legends: The Poetic Edda. An HTML version transcribed with new annotations by Ari Odhinnsen is available at Northvegr: Lore: Poetic Edda - Bellows Trans..)</ref>. Brynhildr herself killed Sigurðr's three-year-old son, and then she willed herself to die. When Sigurðr's funeral pyre was aflame, she threw herself upon it – thus they passed on together to the realm of [[Hel (realm)|Hel]]. <ref>Byock</ref> | Gjuki's wife, the sorceress [[Grimhild]], wanting Sigurðr married to her daughter [[Gudrun]] ([[Kriemhild]] in Nibelungenlied), prepared a magic potion that made Sigurðr forget about Brynhildr. Sigurðr soon married Gudrun. Hearing of Sigurðr's encounter with the valkyrie, Grimhild decided to make Brynhildr the wife of her son [[Gunnar]] ([[Gunther]] in the Nibelungenlied). Gunnar then sought to court Brynhild but was stopped by a ring of fire around the castle. He tried to ride through the flames with his own horse and then with Sigurðr's horse, [[Grani]], but still failed. Sigurðr then exchanged shapes with him and entered the ring of fire. Sigurðr (disguised as Gunnar) and Brynhildr married, and they stayed there three nights, but Sigurðr laid his sword between them (meaning that he did not take her virginity before giving her to the real Gunnar). Sigurðr also took the ring Andvarinaut from her finger and later gave it to Gudrun. Gunnar and Sigurðr soon returned to their true forms, with Brynhildr thinking she married Gunnar. However, Gudrun and Brynhild later quarreled over whose husband was greater, Brynhildr boasting that even Sigurðr was not brave enough to ride through the flames. Gudrun revealed that it was actually Sigurðr who rode through the ring of fire, and Brynhildr became enraged. Sigurðr, remembering the truth, tried to console her, but to no avail. Brynhildr plotted revenge by urging Gunnar to kill Sigurðr, telling him that he slept with her in Hidarfjall, which he swore not to do. Gunnar and his brother [[Hogni]] ([[Hagen]] in the [[Nibelungenlied]]) were afraid to kill him themselves, as they had sworn oaths of brotherhood to Sigurðr. They incited their younger brother, [[Gutthorm]] to kill Sigurðr, by giving him a magic potion that enraged him, and he mudered Sigurðr in his sleep. Dying, Sigurðr threw his sword at Gutthorm, killing him. <ref>Byock</ref>(some Eddic poems say Gutthorm killed him in the forest south of the [[Rhine]], also while resting)<ref>"Gudrunarkviða I" in Bellows, Henry Adams. (Trans.). (1923). ''The Poetic Edda: Translated from the Icelandic with an Introduction and Notes''. New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation. Reprinted Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellon Press. ISBN 0-88946-783-8. (Available at Sacred Texts: Sagas and Legends: The Poetic Edda. An HTML version transcribed with new annotations by Ari Odhinnsen is available at Northvegr: Lore: Poetic Edda - Bellows Trans..)</ref>. Brynhildr herself killed Sigurðr's three-year-old son, and then she willed herself to die. When Sigurðr's funeral pyre was aflame, she threw herself upon it – thus they passed on together to the realm of [[Hel (realm)|Hel]]. <ref>Byock</ref> | ||

| + | ===Brynhildr in Other Eddic Poems=== | ||

However, in some [[Poetic Edda|Eddic]] poems such as [[Sigurðarkviða hin skamma]], Gunnar and Sigurðr lay siege to the castle of [[Atli]], Brynhildr's brother. Atli offers his sister's hand in exchange for a truce, which Gunnar accepts. However, Brynhildr has sworn to marry only Sigurðr, so she is deceived into believing that Gunnar is actually Sigurðr. <ref>Bellows</ref> | However, in some [[Poetic Edda|Eddic]] poems such as [[Sigurðarkviða hin skamma]], Gunnar and Sigurðr lay siege to the castle of [[Atli]], Brynhildr's brother. Atli offers his sister's hand in exchange for a truce, which Gunnar accepts. However, Brynhildr has sworn to marry only Sigurðr, so she is deceived into believing that Gunnar is actually Sigurðr. <ref>Bellows</ref> | ||

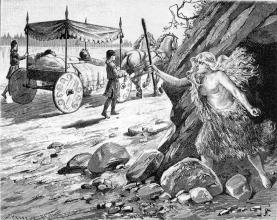

[[Image:Ed0039.jpg|right|thumb|Brynhild's hell-ride by [[Jenny Nyström]].]] | [[Image:Ed0039.jpg|right|thumb|Brynhild's hell-ride by [[Jenny Nyström]].]] | ||

| Line 73: | Line 76: | ||

==Notes== | ==Notes== | ||

<references /> | <references /> | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

| − | + | * Byock, Jesse L. ''The Saga of the Volsungs.'' London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044738-5. | |

* Davidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis. ''Gods and Myths of Northern Europe.'' Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964. ISBN 0317530267. | * Davidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis. ''Gods and Myths of Northern Europe.'' Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964. ISBN 0317530267. | ||

* DuBois, Thomas A. ''Nordic Religions in the Viking Age''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4. | * DuBois, Thomas A. ''Nordic Religions in the Viking Age''. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4. | ||

Revision as of 04:44, 25 March 2007

In Norse mythology, Brynhildr was a shield-maiden and a valkyrie. She is one of the main characters in the Völsunga saga and in some Eddic poems depicting the same events. Under the name Brünnhilde, she also appears in the Nibelungenlied and is therefore present in Richard Wagner's opera cycle Der Ring des Nibelungen.

Brynhildr was probably inspired by the Visigothic princess Brunhilda of Austrasia, who was married to the Merovingian king Sigebert I in 567. Whether this identification is historically accurate, it is compatible with the fact that that many of the valkyries featured in the Poetic Edda are described as mortal women (often of royal blood).

Brynhildr in a Norse Context

As a valkyrie, Brynhildr belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system shared by the Scandinavian and Germanic peoples. This mythological tradition, of which the Scandinavian (and particularly Icelandic) sub-groups are best preserved, developed in the period from the first manifestations of religious and material culture in approximately 1000 B.C.E. until the Christianization of the area, a process that occurred primarily from 900-1200 C.E..[1] The tales recorded within this mythological corpus tend to exemplify a unified cultural focus on physical prowess and military might.

Within this framework, Norse cosmology postulates three separate "clans" of deities: the Aesir, the Vanir, and the Jotun. The distinction between Aesir and Vanir is relative, for the two are said to have made peace, exchanged hostages, intermarried and reigned together after a prolonged war, which the Aesir had finally won. In fact, the most significant divergence between the two groups is in their respective areas of influence, with the Aesir representing war and conquest, and the Vanir representing exploration, fertility and wealth.[2] The Jotun, on the other hand, are seen as a generally malefic (though wise) race of giants who represented the primary adversaries of the Aesir and Vanir.

Valkyries

The primary role of the Valkyries was to swell the ranks of Odin's deathless army by spiriting the "best of the slain" from the battlefield, away to Valhalla. The term itself comes from the Old Norse valkyrja (plural "valkyrur"), which consists of the words val ("to choose") and kyrja ("slaughter"). Thus, the term literally means choosers of the slain. It is cognate to the Old English wælcyrige. The modern German Walküre, which was coined by Richard Wagner, was derived from the Old Norse.[3]

In the mythological poems of the Poetic Edda, the Valkyries are supernatural deities of unknown parentage; they are described as battle-maidens who ride in the ranks of the gods or serve the drinks in Valhalla; they are invariably given unworldly names like Skogul ("Shaker"), Hlok ("Noise", "Battle") and Gol ("Tumult").[4]

Conversely, in the Heroic lays section of the same text, the Valkyries are described as bands of warrior-women, of whom only the leader is ever named. She is invariably a human woman, the beautiful daughter of a great king, though she shares some of the supernatural abilities of her anonymous companions.[5] Brynhildr is the most famous example of this second type of valkyrie.

Mythic Accounts

Brynhildr in the Volsunga Saga

- See also: Sigurd

According to the Völungasaga, Brynhildr is the daughter of Budli. She was ordered to decide a fight between two kings: Hjalmgunnar and Agnar. The valkyrie knew that Odin himself preferred the older king, Hjalmgunnar, yet Brynhildr decided the battle for Agnar. For this Odin condemned the valkyrie to live the life of a mortal woman, and imprisoned her in a remote castle behind a wall of shields on top of mount Hindarfjall in the Alps, and cursed her to sleep until any man would rescue and marry her. The hero Sigurðr Sigmundson (Siegfried in the Nibelungenlied), heir to the clan of Völsung and slayer of the dragon Fafnir, entered the castle and awoke Brynhildr by removing her helmet and cutting off her chainmail armour. He immediately fell in love with the shieldmaiden and proposed to her with the magic ring Andvarinaut. Promising to return and make Brynhildr his bride, Sigurðr then left the castle and headed for the court of Gjuki, the king of Burgundy.[6]

Gjuki's wife, the sorceress Grimhild, wanting Sigurðr married to her daughter Gudrun (Kriemhild in Nibelungenlied), prepared a magic potion that made Sigurðr forget about Brynhildr. Sigurðr soon married Gudrun. Hearing of Sigurðr's encounter with the valkyrie, Grimhild decided to make Brynhildr the wife of her son Gunnar (Gunther in the Nibelungenlied). Gunnar then sought to court Brynhild but was stopped by a ring of fire around the castle. He tried to ride through the flames with his own horse and then with Sigurðr's horse, Grani, but still failed. Sigurðr then exchanged shapes with him and entered the ring of fire. Sigurðr (disguised as Gunnar) and Brynhildr married, and they stayed there three nights, but Sigurðr laid his sword between them (meaning that he did not take her virginity before giving her to the real Gunnar). Sigurðr also took the ring Andvarinaut from her finger and later gave it to Gudrun. Gunnar and Sigurðr soon returned to their true forms, with Brynhildr thinking she married Gunnar. However, Gudrun and Brynhild later quarreled over whose husband was greater, Brynhildr boasting that even Sigurðr was not brave enough to ride through the flames. Gudrun revealed that it was actually Sigurðr who rode through the ring of fire, and Brynhildr became enraged. Sigurðr, remembering the truth, tried to console her, but to no avail. Brynhildr plotted revenge by urging Gunnar to kill Sigurðr, telling him that he slept with her in Hidarfjall, which he swore not to do. Gunnar and his brother Hogni (Hagen in the Nibelungenlied) were afraid to kill him themselves, as they had sworn oaths of brotherhood to Sigurðr. They incited their younger brother, Gutthorm to kill Sigurðr, by giving him a magic potion that enraged him, and he mudered Sigurðr in his sleep. Dying, Sigurðr threw his sword at Gutthorm, killing him. [7](some Eddic poems say Gutthorm killed him in the forest south of the Rhine, also while resting)[8]. Brynhildr herself killed Sigurðr's three-year-old son, and then she willed herself to die. When Sigurðr's funeral pyre was aflame, she threw herself upon it – thus they passed on together to the realm of Hel. [9]

Brynhildr in Other Eddic Poems

However, in some Eddic poems such as Sigurðarkviða hin skamma, Gunnar and Sigurðr lay siege to the castle of Atli, Brynhildr's brother. Atli offers his sister's hand in exchange for a truce, which Gunnar accepts. However, Brynhildr has sworn to marry only Sigurðr, so she is deceived into believing that Gunnar is actually Sigurðr. [10]

According to the Völsunga saga, Brynhildr bore Sigurðr a daughter, Aslaug, who later married Ragnar Lodbrok.

In the Eddic poem Helreið Brynhildar (Bryndhildr's ride to Hel), Brynhildr on her journey to Hel encounters a gýgr (giantess) who blames her for an immoral livelihood. Brynhildr responds to her accusations:

|

|

In Nibelungenlied

In the Nibelungenlied, Brünnhilde is instead the queen of Isenland (Iceland). Gunther here overpowers her in three warlike games with the help of Siegfried – equipped with an invisibility cloak. Firstly, Brünnhilde throws a spear that three men only barely can lift towards Gunther, but the invisible Siegfried diverts it. Secondly, she throws twelve fathoms a boulder that requires the strength of twelve men to lift. Lastly, she leaps over the same boulder. Gunther, however, defeats her with Siegfried's help also in these games, and takes her as his wife.

The Nibelungenlied also differs from Scandinavian sources in its silence on Brünnhilde's fate; she fails to kill herself at Siegfied's funeral, and presumably survives Kriemhild and her brothers.

In Wagner's "Ring" cycle

Though the cycle of four operas is titled Der Ring des Nibelungen, Richard Wagner in fact took Brünnhilde's role from the Norse sagas rather than from the Nibelungenlied. Brünnhilde appears in the latter three operas (Die Walküre, Siegfried, and Götterdämmerung), playing a central role in the overall story of Wotan's downfall.

In Wagner's tale, Brünnhilde is one of Valkyries; but the latter are formed out of a union between Wotan and Erde, a personification of the earth. in Die Walküre Wotan initially commissions her to protect Sigmund, his son by a mortal mother. When Fricka protests and forces Wotan to have Sigmund die, Brünnhilde disobeys her father's change of orders and takes away Sigmund's wife (and sister) Siglinde and the shards of Sigmund's sword Nothung. She manages to hide them but must then face the wrath of her father, who is eventually persuaded to seal her in a ring of fire to await awakening by a hero who does not know fear.

Brünnhilde does not appear again until near the end of the third act of Siegfried. The title character is the son of Sigmund and Siglinde, born after Sigmund's death and raised by the dwarf Mime, the brother of Alberich who stole the gold and fashioned the ring around which the operas are centered. Having himself taken the ring from the giant-turned-dragon Fafner, Siegfried is guided to Brünnhilde's rock, where he awakens her.

Siegfried and Brünnhilde appear again at the beginning of Götterdämmerung, at which point he gives her the ring and they are separated. Here again Wagner chooses to follow the Norse story, though with substantial modifications. Siegfried does go to Gunther's Hall, where he is given a potion to cause him to forget Brünnhilde so that Gunther may marry her. All this occurs at the instigation of Hagen, Alberich's son and Gunther's half-brother. The plan is successful, and Siegfried leads Gunther to Brünnhilde's rock. In the meantime she has been visited by her sister valkyrie Waltraute, who warns her of Wotan's plans for self-immolation and urges her to give up the ring. Brünnhilde refuses, only to be overpowered by Siegfried who, disguised as Gunther, takes the ring from her by force.

As Siegfried goes to marry Gutrune, Gunther's sister, Brünnhilde sees that he has the ring and denounces him for his treachery. Still rejected, she joins Gunther and Hagan in a plot to murder Siegfried, telling Hagen that Siegfried can only be attacked from the back. So Gunther and Hagen take Siegfried on a hunting trip, in the course of which Hagen stabs Siegfried in the back with a spear. Upon their return, Brünnhilde takes charge, and has a pyre built in which she is to perish, cleansing the ring of its curse and returning it to the Rhinemaidens. Her pyre becomes the signal by which Valhalla also perishes in flame.

Notes

- ↑ Lindow, 6-8. Though some scholars have argued against the homogenizing effect of grouping these various traditions together under the rubric of “Norse Mythology,” the profoundly exploratory/nomadic nature of Viking society tends to overrule such objections. As Thomas DuBois cogently argues, “[w]hatever else we may say about the various peoples of the North during the Viking Age, then, we cannot claim that they were isolated from or ignorant of their neighbors…. As religion expresses the concerns and experiences of its human adherents, so it changes continually in response to cultural, economic, and environmental factors. Ideas and ideals passed between communities with frequency and regularity, leading to and interdependent and intercultural region with broad commonalities of religion and worldview.” (27-28).

- ↑ More specifically, Georges Dumézil, one of the foremost authorities on the Norse tradition and a noted comparitivist, argues quite persuasively that the Aesir / Vanir distinction is a component of a larger triadic division (between ruler gods, warrior gods, and gods of agriculture and commerce) that is echoed among the Indo-European cosmologies (from Vedic India, through Rome and into the Germanic North). Further, he notes that this distinction conforms to patterns of social organization found in all of these societies. See Georges Dumézil's Gods of the Ancient Northmen (especially pgs. xi-xiii, 3-25) for more details.

- ↑ "Valkyrie". Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved on 9 August 2006. See also: Orchard, 376.

- ↑ See Orchard's "Appendix D: Names of Troll-wives, Giantesses, and Valkyries" (421-423). For accounts of the valkyries in the Poetic Edda, see Voluspa or Grimnismol, both accessible online.

- ↑ These heroic lays are all found in the second half of the Poetic Edda, accessible online at sacred-texts.com.

- ↑ Byock, Jesse L. The Saga of the Volsungs. London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044738-5.

- ↑ Byock

- ↑ "Gudrunarkviða I" in Bellows, Henry Adams. (Trans.). (1923). The Poetic Edda: Translated from the Icelandic with an Introduction and Notes. New York: American-Scandinavian Foundation. Reprinted Lewiston, NY: Edwin Mellon Press. ISBN 0-88946-783-8. (Available at Sacred Texts: Sagas and Legends: The Poetic Edda. An HTML version transcribed with new annotations by Ari Odhinnsen is available at Northvegr: Lore: Poetic Edda - Bellows Trans..)

- ↑ Byock

- ↑ Bellows

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Byock, Jesse L. The Saga of the Volsungs. London: Penguin, 1990. ISBN 0-14-044738-5.

- Davidson, Hilda Roderick Ellis. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. Baltimore: Penguin Books, 1964. ISBN 0317530267.

- DuBois, Thomas A. Nordic Religions in the Viking Age. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1999. ISBN 0-8122-1714-4.

- Dumézil, Georges. Gods of the Ancient Northmen. Edited by Einar Haugen; Introduction by C. Scott Littleton and Udo Strutynski. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1973. ISBN 0-520-02044-8.

- Lindow, John. Handbook of Norse mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 1-57607-217-7.

- Munch, P. A. Norse Mythology: Legends of Gods and Heroes. In the revision of Magnus Olsen; translated from the Norwegian by Sigurd Bernhard Hustvedt. New York: The American-Scandinavian foundation; London: H. Milford, Oxford University Press, 1926.

- Orchard, Andy. Cassell's Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. London: Cassell; New York: Distributed in the United States by Sterling Pub. Co., 2002. ISBN 0-304-36385-5.

- The Poetic Edda. Translated and with notes by Henry Adams Bellows. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1936. 151-173. Accessed online at sacred-texts.com.

- Sturlson, Snorri. The Prose Edda of Snorri Sturluson: Tales from Norse Mythology. Introduced by Sigurdur Nordal; Selected and translated by Jean I. Young. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 1954. ISBN 0-520-01231-3.

- Sturluson, Snorri. The Prose Edda. Translated from the Icelandic and with an introduction by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. New York: American-Scandinavian foundation, 1916. Available online at http://www.northvegr.org/lore/prose/index.php.

- Turville-Petre, Gabriel. Myth and Religion of the North: The Religion of Ancient Scandinavia. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964. ISBN 0837174201.

Category; Religion

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.