Battle of Agincourt

| Battle of Agincourt | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Hundred Years' War | |||||||

The Battle of Agincourt, 15th century miniature | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Kingdom of England | Kingdom of France | ||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

| Henry V of England | Charles d'Albret | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| About 6,000 (but see Modern re-assessment). 5/6 longbowmen, 1/6 dismounted men-at-arms. | Between 20,000 and 30,000 (but see Modern re-assessment). Estimated to be 1/6 crossbowmen and archers, 1/2 dismounted men-at-arms, 1/3 mounted knights. | ||||||

| Casualties | |||||||

| 100-250 Casualties[1] | Around 6,000 | ||||||

| Hundred Years' War |

|---|

| Edwardian – Breton Succession – Castilian – Two Peters – Caroline – Lancastrian |

| Hundred Years' War (1415-1453) |

|---|

| Agincourt – Rouen – Baugé – Meaux – Cravant – Verneuil – Orléans – Jargeau – Meung-sur-Loire – Beaugency – Patay – Compiègne – Gerbevoy – Formigny – Castillon |

The Battle of Agincourt (IPA pronunciation: [/ɑːʒɪn'kuːʁ/]) was fought on October, 25 1415 (Saint Crispin's Day), in northern France as part of the Hundred Years' War.

The armies involved were those of the English King Henry V and Charles VI of France. Charles did not command his army himself, as he was incapacitated. The French were commanded by the Constable Charles d'Albret and various prominent French noblemen of the Armagnac party. The battle is notable for the use of the English longbow, which the English used in very large numbers, with long bowmen forming the vast majority of their army. The battle was also immortalized by William Shakespeare as the centerpiece of his play Henry V.

The campaign

Henry V invaded France for several reasons. He hoped that by fighting a popular foreign war, he would strengthen his position at home. He wanted to improve his finances by gaining revenue-producing lands. He also wanted to take nobles prisoner either for ransom or to extort money from the French king in exchange for their return. Evidence also suggests that several lords in the region of Normandy promised Henry their lands when they died, but the King of France confiscated their lands instead.

Henry's army landed in northern France on August, 13 1415 and besieged the port of Harfleur with an army of about 12,000. The siege took longer than expected. The town surrendered on 22 September, and the English army did not leave until 8 October. The campaign season was coming to an end, and the English army had suffered many casualties through disease. Henry decided to move most of his army (roughly 7,000) to the port of Calais, the only English stronghold in northern France, where they could re-equip over the winter.

During the siege, the French had been able to call up a large feudal army which d'Albret deployed between Harfleur and Calais, mirroring the English maneuvers along the river Somme, thus preventing them from reaching Calais without a major confrontation. The result was that d'Albret managed to force Henry into fighting a battle that, given the state of his army, he would have preferred to avoid. The English had very little food, had marched 260 miles in two and a half weeks, were suffering from sickness such as dysentery, and faced large numbers of experienced, well equipped Frenchmen.

However, the French suffered a catastrophic defeat, not just in terms of the sheer numbers killed, but because of the number of high-ranking nobles lost. Henry was able to fulfill all his objectives. He was recognized by the French in the Treaty of Troyes (1420) as the regent and heir to the French throne. This was cemented by his marriage to Catherine of Valois, the daughter of King Charles VI.

Despite this, Henry did not live to inherit the throne of France. In 1422, while securing his position against further French opposition, he died of dysentery at the age of 34. When Charles died, two months later, he was succeeded by Charles VII.

Henry was succeeded by his young son, Henry VI, under whose reign the English were expelled from all of France except Calais, by French forces inspired by Joan of Arc.

The battle

Situation

Henry and his troops were marching to Calais to embark for England when he was intercepted by French forces which outnumbered his.

The lack of reliable and consistent sources makes it very difficult to accurately estimate the numbers on both sides. Estimates vary from 6,000 to 9,000 for the English, and from about 15,000 to about 36,000 for the French. Some modern research has questioned whether the English were as outnumbered as traditionally thought (see below). The English were probably not outnumbered as badly as the legend would have it; however, most modern historians (for example, Juliet Barker, Christopher Hibbert) would accept that they were outnumbered by three to one or more.

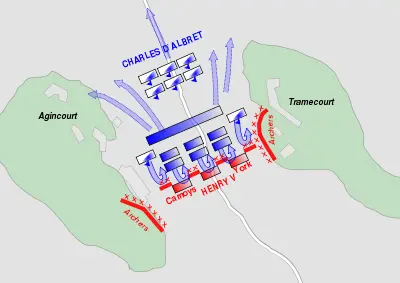

The battle was fought in the narrow strip of open land formed between the woods of Tramecourt and Agincourt (close to the modern village of Azincourt). The French army was positioned by d'Albret at the northern exit so as to bar the way to Calais. The night of 24 October was spent by the two armies on open ground, and the English had little shelter from the heavy rain.

Early on the 25th, Henry deployed his army (approximately 900 men-at-arms and 5,000 longbowmen) across a 750 yard part of the defile. It is likely that the English adopted their usual battle line of long bowmen on either flank, men-at-arms and knights in the center, and at the very center roughly 200 archers. The English men-at-arms in plate and mail were placed shoulder to shoulder four deep. The English archers on the flanks drove pointed wooden stakes called palings into the ground at an angle to force cavalry to veer off. It has been argued that fresh men were brought in after the siege of Harfleur; however, other historians argue that this is wrong, and that although 9,200 English left Harfleur, after more sickness set in, they were down to roughly 5,900 by the time of the battle.

French accounts state that, prior to the battle, Henry V gave a speech reassuring his nobles that if the French prevailed, the English nobles would be spared, to be captured and ransomed instead. However, the common soldier would have no such luck and therefore he told them they had better fight for their lives.

The French were arrayed in three lines called "battles", each with roughly 6,000; however, the first is thought to have swelled to nearly 9,000. Situated on each flank were smaller "wings" of mounted men-at-arms and French Nobles (probably 2,400 in total, 1,200 on each wing), while the centre contained dismounted men-at-arms, many of whom were French scions, including twelve princes of royal blood. The rear was made up of 6,000-9,000 (some sources estimate lower, some estimate higher) of late arriving men-at-arms and armed servants known as "gros varlets" . The 4,000-6,000 French crossbowmen and archers were posted in front of the men-at-arms in centre.

The terrain

Arguably, the deciding factor for the outcome was the terrain. The narrow field of battle, recently ploughed land hemmed in by dense woodland, favored the English.[2][3] Recent analysis (see Battlefield Detectives link) has looked at the crowd dynamics of the battlefield. The 900 English men-at-arms are described as shoulder to shoulder and four deep, which implies a tight line about 225 men long (perhaps split in two by a central group of archers). The remainder of the field would have been filled with the long bowmen behind their palings. The French first line contained between six and nine thousand men-at-arms, outnumbering the English men-at-arms more than six to one, but they had no way to outflank the English line. The French, divided into the three battles, one behind the other at their initial starting position, could not bring all their forces to bear: the initial engagement was between the English army and the first battle line of the French. When the second French battle line started their advance, the soldiers were pushed closer together and their effectiveness was reduced. Casualties in the front line from longbow fire would also have increased the congestion, as following men would have to walk around the fallen. The Battlefield Detectives state that when the density reached four men per square meter, soldiers would not even be able to take full steps forward, lowering the speed of the advance by 70percent. Accounts of the battle describe the French engaging the English men-at-arms before being rushed from the sides by the long bowmen as the melee developed. Engaging the English men-at-arms on the same frontage implies a group at least 25 deep, all trying to press forward into the battle. Although the French initially pushed the English back, they became so closely packed that they are described as having trouble using their weapons properly. In practice there was not enough room for all these men to fight, and they were unable to respond effectively when the English longbowmen joined the hand-to-hand fighting. By the time the second French line arrived, for a total of approximately 12,000 men, the crush would have been even worse. The press of men arriving from behind actually hindered those fighting at the front.

As the battle was fought on a recently plowed field, and there had recently been heavy rain leaving it very muddy, it proved very tiring to walk through in full plate armor. The deep, soft mud particularly favored the English force because, once knocked to the ground, the heavily armored French knights struggled to get back up to fight in the melee. Barker (2005) states that several knights, encumbered by their armor, actually drowned in it. Their limited mobility made them easy targets for the volleys from the English archers. The mud also increased the ability of the much more lightly armored English archers to join in hand-to-hand fighting against the heavily armed French men-at-arms.

The fighting

On the morning of the 25th the French were still waiting for additional troops to arrive. The Duke of Brabant, the Duke of Anjou and the Duke of Brittany, each commanding 1,000–2,000 fighting men, were all marching to join the army. This left the French with a question of whether or not to advance towards the English.

For three hours after sunrise there was no fighting, until Henry, finding that the French would not advance, moved his army further into the defile. Within extreme bowshot from the French line (300 yards), the archers dug in palings (long stakes pointed outwards toward the enemy), and opened the engagement with a barrage of arrows. The use of palings was an innovation: during the battles of Crécy and Poitiers, two similar engagements between the French and the English, the archers did not use them.

The French at this point lost some of their discipline and the mounted wings charged the long bowmen, but it was a disaster, with the French knights unable to outflank the long bowmen (because of the encroaching woodland) and unable to charge through the palings that protected the archers. Keegan (1976) argues that the longbows' main influence on the battle was at this point: only armored on the head, many horses would have become dangerously out of control when struck in the back or flank from the high-elevation shots used as the charge started. The effect of the mounted charge and then retreat was to further churn up the mud the French had to cross to reach the English. Barker (2005) quotes a contemporary account by a monk of St. Denis who reports how the panicking horses also galloped back through the advancing infantry, scattering them and trampling them down in their headlong flight.

Following the knights' charge, the constable himself then led the attack by the line of dismounted men-at-arms. They outnumbered the English men-at-arms by several times, but weighed down by armor and sinking deep into the mud with every step, they struggled to close the distance and reach their enemies. The mud was knee-deep or worse in places, and the French men-at-arms would have been very slow, and easy targets for the English bowmen. Armour technology at this stage in history had become more advanced than in the earlier medieval period but was still vulnerable to longbow arrows, especially at close ranges where the longbow was said to have penetrated plate visors and armor as if it were cloth. However, the archers quickly ran out of arrows and resorted to the daggers, or leaden mallets many of them carried to drive in the stakes, and engaged the French knights [4].

The thin line of English men-at-arms was pushed back and Henry himself was almost beaten to the ground. However, because of the number of men they had brought into the battlefield, and the fact that the battlefield narrowed towards the English end, the French found themselves far too closely packed, and had trouble using their weapons properly. (Keegan 1976) At this moment, the archers, using hatchets, swords and other weapons, attacked the now disordered and fatigued French, who could not cope with their unarmored assailants (who were much less hindered by the mud), and were slaughtered or taken prisoner. By this time the second line of the French had already attacked, only to be engulfed in the mêlée. Its leaders, like those of the first line, were killed or captured, and the commanders of the third line sought and found their death in the battle, while their men rode off to safety.

One of the best anecdotes of the battle involves Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, Henry V's youngest brother. According to the story, Henry, upon hearing that his brother had been wounded in the abdomen, took his household guard and cut a path through the French, standing over his brother and beating back waves of soldiers until Humphrey could be dragged to safety.

The only French success was a sally from Agincourt Castle behind the lines. Ysambart D'Agincourt with 1,000 peasants seized the King's baggage. Thinking his rear was under attack and worried that the prisoners would rearm themselves with the weapons strewn upon the field, Henry ordered their slaughter. The nobles and senior officers, wishing to ransom the captives (and perhaps from a sense of honor, having received the surrender of the prisoners), refused. The task fell to the common soldiers. It is believed more Frenchmen died in this slaughter than in the battle itself.

The aftermath

The next morning, Henry returned to the battlefield and ordered the killing of any wounded Frenchmen who had survived the night out in the open. All of the nobility had already been taken away. It is likely that any commoners left on the field were too badly injured to survive without medical care.

Due to a lack of reliable sources it is impossible to give a precise figure for the French and English casualties. However, it is clear that though the English were considerably outnumbered, their losses were much lower than those of the French.

Claims that the English lost only thirteen men-at-arms (including Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York, a grandson of Edward III) and about 100 foot soldiers are quite unlikely, given the ferocity of the fighting. Henry deliberately concealed the actual losses by paying the English retinues at their pre-battle strengths while quickly spreading the story of only minor losses which persists to this day. One fairly widely used estimate puts the English casualties at 450, not an insignificant number in an army of 6,000, but far less than the thousands the French lost.

The French suffered heavily, mainly because of the massacre of the prisoners. The constable, three dukes, five counts and 90 barons (see below) were among the dead, and a number of notable prisoners were taken, amongst them the Duke of Orléans (the famous poet Charles d'Orléans) and Jean Le Maingre, Marshal of France.

The Battle of Agincourt did not result in Henry conquering France, but it did allow him to escape and renew the war two years later.

Notable casualties

- Antoine of Burgundy, Duke of Brabant and Limburg (b. 1384)

- Philip of Burgundy, Count of Nevers and Rethel (b. 1389)

- Charles I d'Albret, Count of Dreux, the Constable of France

- John II, Count of Bethune (b. 1359)

- John I, Duke of Alençon (b. 1385)

- Frederick of Lorraine, Count of Vaudemont (b. 1371)

- Robert, Count of Marles and Soissons

- Edward III, Duke of Bar (the Duchy of Bar lost its independence as a consequence of his death)

- John VI, Count of Roucy

- Edward of Norwich, 2nd Duke of York (b. 1373)

- Earl of Suffolk

Sir Peers Legh

When Sir Peers Legh was wounded, his mastiff stood over him and protected him for many hours through the battle. Although Legh later died, the mastiff returned to Legh's home and became the forefather of the Lyme Park mastiffs. Five centuries later, this pedigree figured prominently in founding the modern English Mastiff breed.

Modern re-assessment of Agincourt

Were the English as outnumbered as traditionally thought?

Until recently, Agincourt has been feted as one of the greatest victories in English military history. But, in Agincourt, A New History (2005), Anne Curry makes the claim that the scale of the English triumph at Agincourt was overstated for almost six centuries.

According to her research, the French still outnumbered the English and Welsh but at worst only by a factor of three to two (12,000 Frenchmen against 8,000 Englishmen). According to Curry, the Battle of Agincourt was a "myth constructed around Henry to build up his reputation as a king". The legend of the English as underdogs at Agincourt was definitely given credence in popular English culture with William Shakespeare's Henry V in 1599. In the speech before the battle, Shakespeare puts in the mouth of Henry V the famous words, "We few, we happy few, we band of brothers," immediately after numbering English troops at twelve thousand, versus sixty thousand Frenchman. Furthermore, Shakespeare seriously overstated the French casualties and understated the English, even by the traditional count; at the end (Act IV, Scene 8), when Henry's herald delivers the death toll, the numbers are 10,000 French dead and just 29 English.

The primary sources themselves generally do not agree on the numbers of the combatants involved. For example, Enguerrand the Monstrelet, a chronicler writing thirty-eight years after the battle, gave a number of 13,000 archers and 2,000 men-at-arms for the English while the French first and second battles plus the two mounted wings added up to 25,000 men. He does not provide any numbers for the mounted reserve that made up the third battle, stating only that it ran away upon seeing the English victory over the first and second battles.

Juliet Barker in Agincourt: The King, the Campaign, the Battle, claims 6,000 English and Welsh fought against 36,000 French, from a French heraldic source.

Many documentaries about the Battle of Agincourt use the figures of about 6,000 English and 36,000 French, with a French superiority in numbers of 6–1. This is almost certainly an exaggeration; even Shakespeare only puts the odds at 5–1. The 1911 Encylopædia Britannica puts the English at 6,000 archers, 1,000 men-at-arms and "a few thousands of other foot", with the French outnumbering them by "at least four times". Other historians put the English numbers at 6,000 and the French numbers at 20,000–30,000, which would also be consistent with the English being outnumbered 4–1. Curry's research is currently alone in putting the odds at significantly less than this.

Fingering a popular myth

According to a popular myth the "two-fingers salute" and/or V sign derives from the gestures of long bowmen fighting in the English army at the battle of Agincourt. The myth claims that the French cut off two fingers on the right hand of captured archers and that the gesture was a sign of defiance by those who were not mutilated. (This false etymology has also given rise to an alternative name for the gesture, which can also be known as flicking an "Archers Salute" or just "Archers" as in "He just flicked me an Archers!") The website Snopes [1], however, shows that medieval warriors had no interest in capturing common archers that could not be held for ransom, preferring instead to simply kill such prisoners. Furthermore, mutilating a prisoner to stop them from using a bow would not make sense, since killing them would stop them from ever serving the enemy again. There is also the fact that contemporary accounts of the battle make no references to the French mutilating their prisoners by cutting off fingers from their hands.[2] (The first definitive known reference to the V sign is in the works of François Rabelais, a French satirist of the 1500s. [3])

The belief that the V sign originated among archers might have its origin in the work of the historian Jean Froissart (c. 1337–c. 1404), who died before the Battle of Agincourt took place. In his Chronicles, he recounts a story of the English waving their fingers at the French during a siege of a castle, however he makes no reference to which fingers were used meaning that this is not evidence of the origin of the V sign.

The "two-fingers salute" is certainly older than Agincourt. It appears in the Macclesfield Psalter MS 1-2005 Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, believed to be produced in about 1330, Folio 130 Recto, CDROM p261, being made by a glove on the extended nose of a marginalia depicting a human headed hybrid beast, ridden by a person playing the pipe and tabor. The Psalter marginalia have many absurdities and obscenities so the traditional meaning of this gesture would not be out of place here. As the gesture is made by a disembodied glove accidental positioning of the hand may be ruled out.

Notes

- ↑ Trevor Dupuy, Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. p. 450. However, "..it is likely that casualties were substantially greater than this."

- ↑ Wason, David (2004). Battlefield Detectives. London: Carlton Books, p74. ISBN 0233050833.

- ↑ Holmes, Richard (1996). War Walks. London: BBC Worldwide Publishing, p48. ISBN 0-563-38360-7.

- ↑ Barker, 2005

Bibliography

- Barker, Juliet (2005). Agincourt: The King, the Campaign, the Battle Pub: Little, Brown. ISBN 978-0-316-72648-1 (UK). ISBN 978-0-316-01503-5 (U.S.: Agincourt : Henry V and the Battle That Made England (2006)).

- Curry, Anne (2005). Agincourt: A New History. Pub: Tempus UK. ISBN 978-0-7524-2828-4

- "Battle of Agincourt" in Military Heritage, October 2005, Volume 7, No. 2, pp. 36 to 43). ISSN 1524-8666.

- Dupuy, Trevor N. (1993). Harper Encyclopedia of Military History. Pub: New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-270056-8

- Hibbert, Christopher (1971). Great Battles—Agincourt. London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson. ISBN 1842127187.

- Keegan, John (1976). The Face of Battle: A Study of Agincourt, Waterloo, and the Somme. Pub: Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-14-004897-1 (Penguin Classics Reprint)

- The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge Macclesfield Psalter CD, e-mail fitzmuseum-enquiries@lists.cam.ac.uk

External links

- Battlefield Detectives - Agincourt. Crowd Dynamics Ltd Battlefield Detectives - Agincourt. Retrieved September 9, 2005.

- Agincourt A fairly detailed treatment of the battle.

- The Battle of Agincourt Resource Site

- The Agincourt Honor Roll

- BBC - The Battle of Agincourt and English claims to the French Crown 1415 - 1422

- Agincourt with Anne Curry, Michael Jones and John Watts from In Our Time (BBC Radio 4)

- Agincourt 1415: Henry V, Sir Thomas Erpingham and the triumph of the English archers ed. Anne Curry, Pub: Tempus UK, 2000 ISBN 0752417800

- The Battle of Agincourt Bibliography

- The Azincourt Alliance, which arranges re-enactments of the battle at modern-day Azincourt

- The Battle of Agincourt by Steve Beck

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.