Difference between revisions of "Atum" - New World Encyclopedia

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) |

Chris Jensen (talk | contribs) m (→Creator) |

||

| Line 13: | Line 13: | ||

===Creator=== | ===Creator=== | ||

| − | In an early version of the Enneadic | + | In an early version of the Enneadic cosmogony, Atum was seen as the solitary, primordial living being, having arisen by his own force from the chaotic waters of Nun. Once he emerged onto the primordial mound (''benben''), he took it upon himself to create the cosmos (personalized as [[Shu]] (air) and [[Tefnut]] (moisture), and their children [[Geb]] (earth) and [[Nut]] (sky)). To accomplish this feat, the monadic deity proceeded to loose his vital fluids (either spittle, mucus, or semen) upon the waiting earth, from which sprang up the second generation of divinities.<ref>Wilkinson, 99; Zivie-Coche, 48, 55. See also: [http://www.philae.nu/akhet/NetjeruA.html#Atum Egyptian gods Atum] URL accessed August 16, 2007.</ref> Two early versions of the creation tale are found in the Pyramid Texts. In the first, creation occurs through masturbation; in the second, it happens through expectoration.<ref>Some sources argue that this second case of creation is actually a veiled reference to auto-fellatio. See, for example, Najovits, 104-105.</ref> |

:''Pyramid Texts (Utterance 527)'' | :''Pyramid Texts (Utterance 527)'' | ||

:To say: Atum created by his masturbation in Heliopolis. | :To say: Atum created by his masturbation in Heliopolis. | ||

| Line 24: | Line 24: | ||

:and didst shine as bnw of the ben (or, benben) in the temple of the "phoenix" in Heliopolis, | :and didst shine as bnw of the ben (or, benben) in the temple of the "phoenix" in Heliopolis, | ||

:and didst spew out as Shu, and did spit out as Tefnut, | :and didst spew out as Shu, and did spit out as Tefnut, | ||

| − | :(then) thou didst put thine arms about them, as the arm(s) of a ka, that thy ka might be in them.<ref>[http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/pyt43.htm Pyramid Texts] 600 (1652a-1653a). Retrieved August 16, 2007.</ref> | + | :(then) thou didst put thine arms about them, as the arm(s) of a ka, that thy ka might be in them.<ref>[http://www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/pyt43.htm Pyramid Texts] 600 (1652a-1653a). Retrieved August 16, 2007. This auto-creative process (coupled with the emergence of the primordial mound) is also described in Spell 80 B1C of the ''Coffin Texts'' (quoted in Zivie-Coche, 50-51).</ref> |

| + | An important religious theme, addressed for the first time in this text, is the idea that the actual substance (in this case, the soul or ''ka'') of the creator is passed onto and possessed by His creation. Such a [[monism|monistic]]/[[monotheism|monotheistic]] notion, which achieved fruition under [[Akhenaten]], was already implied by the etymological connection between the Atum's name and the notion of "completion" (described above).<ref>Wilkinson, 99.</ref> | ||

| − | + | a belief strongly associated with Atum's nature as an [[hermaphrodite]] (his name meaning ''completeness''). Strictly, the myth states that Atum [[ejaculation|ejaculated]] his Semen into his mouth, impregnating himself, possibly indicating [[autofellatio]], which has lead many to misinterpret ([[euphemism|euphemistically]]) the myth as indicating creation from [[mucus]]. | |

Later belief held that Shu and Tefnut were created by Atum having [[sex]] with his [[shadow]], which was referred to as '''''Iusaaset''''' (also spelt '''Juesaes''', '''Ausaas''', '''Iusas''', and '''Jusas''', and in Greek as '''Saosis'''), meaning ''(the) great (one who) comes forth''. Consequently, Iusaaset was seen as the mother and grandmother of the gods. The strength, [[Hardiness (plants)|hardiness]], [[Pharmaceutical chemistry|medical properties]], and [[edible|edibility]], lead the [[acacia]] tree to be considered the ''[[tree of life]]'', and thus the oldest, which was situated close to, and north of, [[Heliopolis (ancient)|Heliopolis]], was said to be the birthplace of the gods. Thus, as the mother, and grandmother, of the gods, Iusaaset was said to own this tree. | Later belief held that Shu and Tefnut were created by Atum having [[sex]] with his [[shadow]], which was referred to as '''''Iusaaset''''' (also spelt '''Juesaes''', '''Ausaas''', '''Iusas''', and '''Jusas''', and in Greek as '''Saosis'''), meaning ''(the) great (one who) comes forth''. Consequently, Iusaaset was seen as the mother and grandmother of the gods. The strength, [[Hardiness (plants)|hardiness]], [[Pharmaceutical chemistry|medical properties]], and [[edible|edibility]], lead the [[acacia]] tree to be considered the ''[[tree of life]]'', and thus the oldest, which was situated close to, and north of, [[Heliopolis (ancient)|Heliopolis]], was said to be the birthplace of the gods. Thus, as the mother, and grandmother, of the gods, Iusaaset was said to own this tree. | ||

Revision as of 20:10, 16 August 2007

Atum (alternatively spelled Tem, Temu, Tum, and Atem) is an early deity in Egyptian mythology, whose cult centred on the Ennead of Heliopolis. <etymology>

Atum in an Egyptian Context

| Atum in hieroglyphs | |||

|

As an Egyptian deity, Atum belonged to a complex religious, mythological and cosmological belief system developed in the Nile river basin from earliest prehistory to 525 B.C.E.[1] Indeed, it was during this relatively late period in Egyptian cultural development, a time when they first felt their beliefs threatened by foreigners, that many of their myths, legends and religious beliefs were first recorded.[2] The cults within this framework, whose beliefs comprise the myths we have before us, were generally fairly localized phenomena, with different deities having the place of honor in different communities.[3] Despite this apparently unlimited diversity, however, the gods (unlike those in many other pantheons) were relatively ill-defined. As Frankfort notes, “the Egyptian gods are imperfect as individuals. If we compare two of them … we find, not two personages, but two sets of functions and emblems. … The hymns and prayers addressed to these gods differ only in the epithets and attributes used. There is no hint that the hymns were addressed to individuals differing in character.”[4] One reason for this was the undeniable fact that the Egyptian gods were seen as utterly immanental—they represented (and were continuous with) particular, discrete elements of the natural world.[5] Thus, those who did develop characters and mythologies were generally quite portable, as they could retain their discrete forms without interfering with the various cults already in practice elsewhere. Also, this flexibility was what permitted the development of multipartite cults (i.e. the cult of Amun-Re, which unified the domains of Amun and Re), as the spheres of influence of these various deities were often complimentary.[6]

The worldview engendered by ancient Egyptian religion was uniquely appropriate to (and defined by) the geographical and calendrical realities of its believer’s lives. Unlike the beliefs of the Hebrews, Mesopotamians and others within their cultural sphere, the Egyptians viewed both history and cosmology as being well ordered, cyclical and dependable. As a result, all changes were interpreted as either inconsequential deviations from the cosmic plan or cyclical transformations required by it.[7] The major result of this perspective, in terms of the religious imagination, was to reduce the relevance of the present, as the entirety of history (when conceived of cyclically) was ultimately defined during the creation of the cosmos. The only other aporia in such an understanding is death, which seems to present a radical break with continuity. To maintain the integrity of this worldview, an intricate system of practices and beliefs (including the extensive mythic geographies of the afterlife, texts providing moral guidance (for this life and the next) and rituals designed to facilitate the transportation into the afterlife) was developed, whose primary purpose was to emphasize the unending continuation of existence.[8] Given these two cultural foci, it is understandable that the tales recorded within this mythological corpus tended to be either creation accounts or depictions of the world of the dead, with a particular focus on the relationship between the gods and their human constituents.

Mythological Accounts

In the archaic Egyptian pantheon, Atum was the chief god in the Ennead of Heliopolis (the capital of the Lower Kingdom). This place of primacy in early religious thought is attested to in the Pyramid Texts, where he receives more attention than many other gods combined.[9] In spite of his early prominence, the various roles originally filled by Atum were eventually assumed by other gods, including Horus (who eventually came to be seen as the preeminent god of kings), and Ra/Amun (both of whom inherited his solar and creative aspects). Despite the waning of his influence, Atum remained a vibrant part of Egyptian myth and religious observance throughout the dynastic history and into the Common Era.

Creator

In an early version of the Enneadic cosmogony, Atum was seen as the solitary, primordial living being, having arisen by his own force from the chaotic waters of Nun. Once he emerged onto the primordial mound (benben), he took it upon himself to create the cosmos (personalized as Shu (air) and Tefnut (moisture), and their children Geb (earth) and Nut (sky)). To accomplish this feat, the monadic deity proceeded to loose his vital fluids (either spittle, mucus, or semen) upon the waiting earth, from which sprang up the second generation of divinities.[10] Two early versions of the creation tale are found in the Pyramid Texts. In the first, creation occurs through masturbation; in the second, it happens through expectoration.[11]

- Pyramid Texts (Utterance 527)

- To say: Atum created by his masturbation in Heliopolis.

- He put his phallus in his fist,

- to excite desire thereby.

- The twins were born, Shu and Tefnut.[12]

- Pyramid Texts (Utterance 600)

- To say: O Atum-Khepri, when thou didst mount as a hill,

- and didst shine as bnw of the ben (or, benben) in the temple of the "phoenix" in Heliopolis,

- and didst spew out as Shu, and did spit out as Tefnut,

- (then) thou didst put thine arms about them, as the arm(s) of a ka, that thy ka might be in them.[13]

An important religious theme, addressed for the first time in this text, is the idea that the actual substance (in this case, the soul or ka) of the creator is passed onto and possessed by His creation. Such a monistic/monotheistic notion, which achieved fruition under Akhenaten, was already implied by the etymological connection between the Atum's name and the notion of "completion" (described above).[14]

a belief strongly associated with Atum's nature as an hermaphrodite (his name meaning completeness). Strictly, the myth states that Atum ejaculated his Semen into his mouth, impregnating himself, possibly indicating autofellatio, which has lead many to misinterpret (euphemistically) the myth as indicating creation from mucus.

Later belief held that Shu and Tefnut were created by Atum having sex with his shadow, which was referred to as Iusaaset (also spelt Juesaes, Ausaas, Iusas, and Jusas, and in Greek as Saosis), meaning (the) great (one who) comes forth. Consequently, Iusaaset was seen as the mother and grandmother of the gods. The strength, hardiness, medical properties, and edibility, lead the acacia tree to be considered the tree of life, and thus the oldest, which was situated close to, and north of, Heliopolis, was said to be the birthplace of the gods. Thus, as the mother, and grandmother, of the gods, Iusaaset was said to own this tree.

Solar Deity

Originally associated with the earth, Atum gradually became considered to be the sun, as it passes the horizon. The separateness of the two instances per day that this occurs, led to the aspect of Atum that was young, namely the rising sun, becoming considered a separate god, named Nefertum (literally meaning young Atum), and consequently Atum became mainly understood as the setting sun.

In later years, the Ennead mythos, and an alternative mythos, that of the Ogdoad, merged, and since Ra, from the Ogdoad, was also the creator (in that system), and a solar deity, their two identities merged, into Atum-Ra. But as Ra was the whole sun, and Atum just the sun when it sets, it was Atum who was thought of as an aspect of Ra, and eventually subsumed into him. When this happened, his shadow, Iusaaset, was described as Rat, which is simply the feminine form of Ra. As both the cosmogony associated with Ra and that of Atum said that the origin of each was the primordial waters, when, in later years, Neith came to embody these waters, Iusaaset became considered an aspect of Neith rather than Atum-Ra.

Atum and the Pharaohs

At one point Egyptians believed that Atum lifted the dead king's soul from his pyramid to the starry heavens.[15]

Iconography

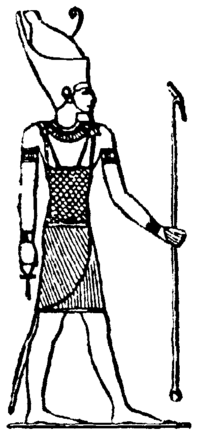

In art, Atum was always considered as a man, enthroned, or sometimes standing, and depicted wearing both the crown of Upper Egypt, and that of Lower Egypt. In his later form as the setting sun, as opposed to Nefertum, Atum was depicted in the same manner but as an aged man. However, it was sometimes said that Atum was originally a serpent, a form to which he was said to be destined to return when the world ends, only changing into a human during its existence.

Atum was represented as scarab.

Notes

- ↑ This particular "cut-off" date has been chosen because it corresponds to the Persian conquest of the kingdom, which marks the end of its existence as a discrete and (relatively) circumscribed cultural sphere. Indeed, as this period also saw an influx of immigrants from Greece, it was also at this point that the Hellenization of Egyptian religion began. While some scholars suggest that even when "these beliefs became remodeled by contact with Greece, in essentials they remained what they had always been" (Erman, 203), it still seems reasonable to address these traditions, as far as is possible, within their own cultural milieu.

- ↑ The numerous inscriptions, stelae and papyri that resulted from this sudden stress on historical posterity provide much of the evidence used by modern archeologists and Egyptologists to approach the ancient Egyptian tradition (Pinch, 31-32).

- ↑ These local groupings often contained a particular number of deities and were often constructed around the incontestably primary character of a creator god (Meeks and Meeks-Favard, 34-37).

- ↑ Frankfort, 25-26.

- ↑ Zivie-Coche, 40-41; Frankfort, 23, 28-29.

- ↑ Frankfort, 20-21.

- ↑ Assmann, 73-80; Zivie-Coche, 65-67; Breasted argues that one source of this cyclical timeline was the dependable yearly fluctuations of the Nile (8, 22-24).

- ↑ Frankfort, 117-124; Zivie-Coche, 154-166.

- ↑ For instance, Wilkinson notes that he is "one of the eight or nine most frequently mentioned gods in the Pyramid Texts" (99).

- ↑ Wilkinson, 99; Zivie-Coche, 48, 55. See also: Egyptian gods Atum URL accessed August 16, 2007.

- ↑ Some sources argue that this second case of creation is actually a veiled reference to auto-fellatio. See, for example, Najovits, 104-105.

- ↑ Pyramid Texts 527 (1248a-1248d). Retrieved August 16, 2007.

- ↑ Pyramid Texts 600 (1652a-1653a). Retrieved August 16, 2007. This auto-creative process (coupled with the emergence of the primordial mound) is also described in Spell 80 B1C of the Coffin Texts (quoted in Zivie-Coche, 50-51).

- ↑ Wilkinson, 99.

- ↑ [1] - Retrieved November 9, 2006.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

- Assmann, Jan. In search for God in ancient Egypt. Translated by David Lorton. Ithica: Cornell University Press, 2001. ISBN 0801487293.

- Breasted, James Henry. Development of religion and thought in ancient Egypt. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1986. ISBN 0812210454.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Book of the Dead. 1895. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Egyptian Heaven and Hell. 1905. Accessed at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/ehh.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Budge, E. A. Wallis. The gods of the Egyptians; or, Studies in Egyptian mythology. A Study in Two Volumes. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). Legends of the Gods: The Egyptian texts. 1912. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Budge, E. A. Wallis (translator). The Rosetta Stone. 1893, 1905. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dennis, James Teackle (translator). The Burden of Isis. 1910. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Dunand, Françoise and Zivie-Coche, Christiane. Gods and men in Egypt: 3000 B.C.E. to 395 C.E.. Translated from the French by David Lorton. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2004. ISBN 080144165X.

- Erman, Adolf. A handbook of Egyptian religion. Translated by A. S. Griffith. London: Archibald Constable, 1907.

- Frankfort, Henri. Ancient Egyptian Religion. New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1961. ISBN 0061300772.

- Griffith, F. Ll. and Thompson, Herbert (translators). The Leyden Papyrus. 1904. Accessed at sacred-texts.com.

- Klotz, David. Adoration of the Ram: Five Hymns to Amun-Re from Hibis Temple. New Haven, 2006. ISBN 0974002526.

- Larson, Martin A. The Story of Christian Origins. 1977. ISBN 0883310902.

- Meeks, Dimitri and Meeks-Favard, Christine. Daily life of the Egyptian gods. Translated from the French by G.M. Goshgarian. Ithaca, NY : Cornell University Press, 1996. ISBN 0801431158.

- Mercer, Samuel A. B. (translator). The Pyramid Texts. 1952. Accessed online at [www.sacred-texts.com/egy/pyt/index.htm sacred-texts.com].

- Pinch, Geraldine. Handbook of Egyptian mythology. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2002. ISBN 1576072428.

- Shafer, Byron E. (editor). Temples of ancient Egypt. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1997. ISBN 0801433991.

- Wilkinson, Richard H. The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames and Hudson, 2003. ISBN 0500051208.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.