Difference between revisions of "Alcuin" - New World Encyclopedia

({{Contracted}}) |

(→Notes) |

||

| Line 3: | Line 3: | ||

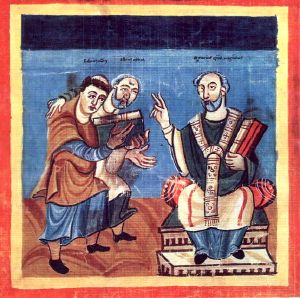

[[Image:Raban-Maur_Alcuin_Otgar.jpg|thumb|[[Rabanus Maurus]] (left), supported by '''Alcuin''' (middle), presents his work to Otgar of Mainz]] | [[Image:Raban-Maur_Alcuin_Otgar.jpg|thumb|[[Rabanus Maurus]] (left), supported by '''Alcuin''' (middle), presents his work to Otgar of Mainz]] | ||

| − | '''Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus''' or '''Ealhwine''' (c. 735 – May 19, [[804 in poetry|804]]) was a scholar, ecclesiastic, poet and teacher from [[York, England]]. He was born around 735 and became the student of Egbert at York. | + | '''Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus''' or '''Ealhwine''' (c. 735 – May 19, [[804 in poetry|804]]) was a scholar, ecclesiastic, poet, and teacher from [[York, England]]. He was born around 735 and became the student of Egbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure at court in the 780s and 790s. He wrote many theological and dogmatic treatises, as well as a few grammatical works and a number of poems. He was made abbot of Saint Martin's at Tours in 796, where he remained until his death. He is considered among the most important architects of the [[Carolingian Renaissance]]. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era. |

== Biography == | == Biography == | ||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

Alcuin came to the cathedral school of York in the golden age of [[Ecgbert, Archbishop of York|Egbert]] and [[Eadberht of Northumbria|Eadbert]]. Egbert had been a disciple of the Venerable [[Bede]] who urged him to have [[York]] raised to an [[archbishopric]]. Eadbert was the king and brother to Egbert. These two men oversaw the re-energizing and reorganization of the [[English church]] with an emphasis on reforming the clergy and on the tradition of learning begun under Bede. Alcuin thrived under Egbert’s tutelage who loved him especially. It was in York that he formed his love of classical poetry, though he was sometimes troubled by the fact that it was written by non-Christians. | Alcuin came to the cathedral school of York in the golden age of [[Ecgbert, Archbishop of York|Egbert]] and [[Eadberht of Northumbria|Eadbert]]. Egbert had been a disciple of the Venerable [[Bede]] who urged him to have [[York]] raised to an [[archbishopric]]. Eadbert was the king and brother to Egbert. These two men oversaw the re-energizing and reorganization of the [[English church]] with an emphasis on reforming the clergy and on the tradition of learning begun under Bede. Alcuin thrived under Egbert’s tutelage who loved him especially. It was in York that he formed his love of classical poetry, though he was sometimes troubled by the fact that it was written by non-Christians. | ||

| − | The York school was renowned as a center of learning not only in religious matters but also in the liberal arts, literature and science named ''the seven liberal arts''. | + | The York school was renowned as a center of learning not only in religious matters but also in the liberal arts, literature and science named ''the seven liberal arts''. It was from here that Alcuin drew inspiration for the school he would lead at the [[Frankish]] court. He revived the school with disciplines such as the [[Trivium (education)|trivium]] and the [[quadrivium]]. Two codices were written, by himself on the trivium, and by his student [[Rabanus Maurus|Hraban]]. |

| − | |||

| − | Alcuin graduated from student to teacher sometime in the 750s. His ascendancy to the headship of the [[York]] school began after [[Ethelbert of York|Aelbert]] became Archbishop of York in 767. | + | Alcuin graduated from student to teacher sometime in the 750s. His ascendancy to the headship of the [[York]] school began after [[Ethelbert of York|Aelbert]] became Archbishop of York in 767. Around the same time Alcuin became a deacon in the church. He was never ordained as a priest and there is no real evidence that he became an actual monk, but he lived his life like one. |

In 781, King [[Ælfwald I of Northumbria|Elfwald]] sent Alcuin to [[Rome]] to petition the [[Pope]] for official confirmation of York’s status as an archbishopric and to confirm the election of a new archbishop, [[Eanbald I]]. It was then, on his way home, that Alcuin met [[Charlemagne|Charles]], king of the [[Franks]]. | In 781, King [[Ælfwald I of Northumbria|Elfwald]] sent Alcuin to [[Rome]] to petition the [[Pope]] for official confirmation of York’s status as an archbishopric and to confirm the election of a new archbishop, [[Eanbald I]]. It was then, on his way home, that Alcuin met [[Charlemagne|Charles]], king of the [[Franks]]. | ||

| Line 19: | Line 18: | ||

Alcuin was reluctantly persuaded to join Charles's court. His love of the church and his intellectual curiosity made the offer one that he could not refuse. He was to join an already illustrious group of scholars that Charles had gathered around him like [[Peter of Pisa]], [[Paulinus]], [[Rado]], and [[Saint Fulrad|Abbot Fulrad]]. He would later write that "the Lord was calling me to the service of King Charles." | Alcuin was reluctantly persuaded to join Charles's court. His love of the church and his intellectual curiosity made the offer one that he could not refuse. He was to join an already illustrious group of scholars that Charles had gathered around him like [[Peter of Pisa]], [[Paulinus]], [[Rado]], and [[Saint Fulrad|Abbot Fulrad]]. He would later write that "the Lord was calling me to the service of King Charles." | ||

| − | Alcuin was welcomed at the [[Charlemagne's Palace in Aachen|Palace]] School of Charlemagne. The school had been founded under the king’s ancestors as a place for educating the royal children, mostly in manners and the ways of the court. However, King Charles wanted more than this – he wanted to include the [[liberal arts]] and, most importantly, the study of the religion that he held sacred. From 782 to 790, Alcuin had as pupils the Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, the young men sent for their education to the court, and the young [[cleric]]s attached to the [[Palatine Chapel in Aachen|palace chapel]]. Bringing with him from York his assistants Pyttel, Sigewulf and Joseph, Alcuin revolutionized the educational standards of the Palace School, introducing Charlemagne to the liberal arts and creating a personalized atmosphere of scholarship and learning to the extent that the institution came to be known as the "school of Master Albinus." | + | Alcuin was welcomed at the [[Charlemagne's Palace in Aachen|Palace]] School of Charlemagne. The school had been founded under the king’s ancestors as a place for educating the royal children, mostly in manners and the ways of the court. However, King Charles wanted more than this – he wanted to include the [[liberal arts]] and, most importantly, the study of the religion that he held sacred. From 782 to 790, Alcuin had as pupils the Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, the young men sent for their education to the court, and the young [[cleric]]s attached to the [[Palatine Chapel in Aachen|palace chapel]]. Bringing with him from York his assistants Pyttel, Sigewulf, and Joseph, Alcuin revolutionized the educational standards of the Palace School, introducing Charlemagne to the liberal arts and creating a personalized atmosphere of scholarship and learning to the extent that the institution came to be known as the "school of Master Albinus." |

| − | Charlemagne was master at gathering the best men of every nation in his court. He himself became far more than just the king at the center. It seems that Charlemagne made many of these men his closest friends and counselors. They referred to him as "David," a reference to the Biblical King [[David]]. | + | Charlemagne was master at gathering the best men of every nation in his court. He himself became far more than just the king at the center. It seems that Charlemagne made many of these men his closest friends and counselors. They referred to him as "David," a reference to the Biblical King [[David]]. Alcuin soon found himself on intimate terms with the king and with the other men at court to whom he gave nicknames to be used for work and play. Alcuin himself was known as "Albinus" or "Flaccus." Like many of his learned contemporaries, Alcuin was an [[astrologer]]. [[David Berlinski]], author of ''The Secrets of the Vaulted Sky: Astrology and the Art of Prediction'' (ISBN 0-15-100527-3) writes: "The ninth-century philosopher Alcuin, his voyages to the [[Middle East]] now abrogated, was an [[astrological]] adept, and it is widely claimed that he taught Charlemagne the principles of [[Western astrology|classical astrology]]" (pg. 116, 2003). |

| − | Alcuin’s friendships also extended to the ladies of the court, especially the queen mother and the daughters of the king. His relationships with these women, however, never reached the intense level of those with the men around him | + | Alcuin’s friendships also extended to the ladies of the court, especially the queen mother and the daughters of the king. His relationships with these women, however, never reached the intense level of those with the men around him. |

| − | In 790 Alcuin went back to England, to which he had always been greatly attached. He dwelt there for some time, but Charlemagne then invited him back to help in the fight against the [[Adoptionism|Adoptionist]] [[Christian heresy|heresy]] which was at that time making great progress in [[Toledo, Spain]], the old capital town of the [[Visigoths]] and still a major city for the Christians under [[Islamic]] rule in Spain. He is believed to have had contacts with [[Beatus of Liébana]], from the [[Kingdom of Asturias]], who fought against Adoptionism. At the [[Council of Frankfurt]] in 794, Alcuin upheld the orthodox doctrine, and obtained the condemnation of the heresiarch [[Felix, Bishop of Urgel|Felix of Urgel]] | + | In 790, Alcuin went back to England, to which he had always been greatly attached. He dwelt there for some time, but Charlemagne then invited him back to help in the fight against the [[Adoptionism|Adoptionist]] [[Christian heresy|heresy]] which was at that time making great progress in [[Toledo, Spain]], the old capital town of the [[Visigoths]] and still a major city for the Christians under [[Islamic]] rule in Spain. He is believed to have had contacts with [[Beatus of Liébana]], from the [[Kingdom of Asturias]], who fought against Adoptionism. At the [[Council of Frankfurt]] in 794, Alcuin upheld the orthodox doctrine, and obtained the condemnation of the heresiarch [[Felix, Bishop of Urgel|Felix of Urgel]]. |

| − | + | Having failed during his stay in England to influence King [[Æthelred_I_of_Northumbria|Aethelraed of Northumbria]] in the conduct of his reign, Alcuin never returned to live in England. Alcuin was back at Charlemagne's court by at least mid 792, writing a series of letters to Aethelraed of Northumbria, to [[Hygbald]], Bishop of [[Lindisfarne]], and [[Æthelhard|Aethelheard]], [[Archbishop of Canterbury]] in the succeeding months, which deal with the attack on Lindisfarne by [[Viking]] raiders in July 792. These letters, and Alcuin's poem on the subject ''De clade Lindisfarnensis monasterii'' provide the only significant contemporary account of these events. | |

| − | == As a Carolingian Renaissance figure == | + | In 796, Alcuin was in his sixties. He hoped to be free from court duties and was given the chance when [[Abbot Itherius]] of [[Saint Martin at Tours]] died. King [[Charlemagne|Charles]] gave the abbey into Alcuin's care with the understanding that he should be available if the king ever needed his counsel. |

| + | |||

| + | ==As a Carolingian Renaissance figure== | ||

He made the abbey school into a model of excellence, and many students flocked to it; he had many manuscripts copied, the [[calligraphy]] of which is of outstanding beauty. He wrote many letters to his friends in England, to [[Arno of Salzburg|Arno, bishop of Salzburg]], and above all to [[Charlemagne]]. These letters, of which 311 are extant, are filled mainly with pious meditations, but they further form a mine of information as to the literary and social conditions of the time, and are the most reliable authority for the history of [[humanism]] in the [[Carolingian]] age. He also trained the numerous monks of the abbey in piety, and it was in the midst of these pursuits that he died. | He made the abbey school into a model of excellence, and many students flocked to it; he had many manuscripts copied, the [[calligraphy]] of which is of outstanding beauty. He wrote many letters to his friends in England, to [[Arno of Salzburg|Arno, bishop of Salzburg]], and above all to [[Charlemagne]]. These letters, of which 311 are extant, are filled mainly with pious meditations, but they further form a mine of information as to the literary and social conditions of the time, and are the most reliable authority for the history of [[humanism]] in the [[Carolingian]] age. He also trained the numerous monks of the abbey in piety, and it was in the midst of these pursuits that he died. | ||

| + | Alcuin died on May 19, 804, some ten years before the emperor. He was buried at St. Martin’s Church under an epitaph that partly read: | ||

| + | {{cquote|Dust, worms, and ashes now...<br/> Alcuin my name, wisdom I always loved,<br/> Pray, reader, for my soul.}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Legacy== | ||

Alcuin is the most prominent figure of the [[Carolingian Renaissance]], in which three main periods have been distinguished: in the first of these, up to the arrival of Alcuin at the court, the [[Italy|Italians]] occupy the central place; in the second, Alcuin and the [[Anglo-Saxons]] are dominant; in the third, which begins in 804, the influence of [[Theodulf]] the Visigoth is preponderant. | Alcuin is the most prominent figure of the [[Carolingian Renaissance]], in which three main periods have been distinguished: in the first of these, up to the arrival of Alcuin at the court, the [[Italy|Italians]] occupy the central place; in the second, Alcuin and the [[Anglo-Saxons]] are dominant; in the third, which begins in 804, the influence of [[Theodulf]] the Visigoth is preponderant. | ||

| Line 38: | Line 43: | ||

Alcuin transmitted to the [[Franks]] the knowledge of Latin culture which had existed in England. We still have a number of his works. His letters have already been mentioned; his [[poetry]] is equally interesting. Besides some graceful epistles in the style of [[Fortunatus]], he wrote some long poems, and notably a whole history in verse of the church at York: ''Versus de patribus, regibus et sanctis Eboracensis ecclesiae''. | Alcuin transmitted to the [[Franks]] the knowledge of Latin culture which had existed in England. We still have a number of his works. His letters have already been mentioned; his [[poetry]] is equally interesting. Besides some graceful epistles in the style of [[Fortunatus]], he wrote some long poems, and notably a whole history in verse of the church at York: ''Versus de patribus, regibus et sanctis Eboracensis ecclesiae''. | ||

| − | Alcuin | + | Alcuin was an advocate on behalf of freedom of conscience. As chief adviser to Charles the Great, he bravely tackled the emperor over his policy of forcing pagans to be baptized on pain of death. He argued, “Faith is a free act of the will, not a forced act. We must appeal to the conscience, not compel it by violence. You can force people to be baptized, but you cannot force them to believe.” His arguments prevailed; Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in 797. (Needham, Dr. N.R., Two Thousand Years of Christ’s Power, Part Two: The Middle Ages, Grace Publications, 2000, page 52.) |

| − | |||

[[Alcuin College]], part of the [[University of York]], is named after him. The [[Alcuin Society]] brings together lovers of books and awards an annual prize for excellence in book design. | [[Alcuin College]], part of the [[University of York]], is named after him. The [[Alcuin Society]] brings together lovers of books and awards an annual prize for excellence in book design. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Further reading == | == Further reading == | ||

| − | *''Alcuin of York, his life and letters'', | + | *Allot, Stephen. ''Alcuin of York, his life and letters'', William Sessions Limited, 1974. ISBN 0-900657-21-9 |

| − | * | + | *Ganshof, F.L. ''The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy'', Longman, 1971. ISBN 0-582-48227-5 |

| − | + | *McGuire, Brian P. ''Friendship, and Community: The Monastic Experience'', Cistercian Publications, 2000. ISBN 0-87907-895-2 | |

| − | + | *West, Andrew Fleming. ''Alcuin and the Rise of the Christian Schools'', Greenwood Press, 1969. ISBN 0-8371-1635-X | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | * | ||

| − | |||

| − | *'' | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

*{{MacTutor Biography|id=Alcuin}} | *{{MacTutor Biography|id=Alcuin}} | ||

*[http://logica.rug.ac.be/albrecht/alcuin.pdf Alcuin's book, ''Problems for the Quickening of the Minds of the Young''] - Retrieved September 19, 2007. | *[http://logica.rug.ac.be/albrecht/alcuin.pdf Alcuin's book, ''Problems for the Quickening of the Minds of the Young''] - Retrieved September 19, 2007. | ||

| − | + | ||

[[Category:Biography]] | [[Category:Biography]] | ||

Revision as of 01:45, 27 November 2007

Flaccus Albinus Alcuinus or Ealhwine (c. 735 – May 19, 804) was a scholar, ecclesiastic, poet, and teacher from York, England. He was born around 735 and became the student of Egbert at York. At the invitation of Charlemagne, he became a leading scholar and teacher at the Carolingian court, where he remained a figure at court in the 780s and 790s. He wrote many theological and dogmatic treatises, as well as a few grammatical works and a number of poems. He was made abbot of Saint Martin's at Tours in 796, where he remained until his death. He is considered among the most important architects of the Carolingian Renaissance. Among his pupils were many of the dominant intellectuals of the Carolingian era.

Biography

Alcuin of York had a long career as a teacher and scholar, first at the school at York now known as St Peter's School, York (founded AD 627) and later as Charlemagne's leading advisor on ecclesiastical and educational affairs. From 796 until his death he was abbot of the great monastery of St. Martin of Tours.

Alcuin came to the cathedral school of York in the golden age of Egbert and Eadbert. Egbert had been a disciple of the Venerable Bede who urged him to have York raised to an archbishopric. Eadbert was the king and brother to Egbert. These two men oversaw the re-energizing and reorganization of the English church with an emphasis on reforming the clergy and on the tradition of learning begun under Bede. Alcuin thrived under Egbert’s tutelage who loved him especially. It was in York that he formed his love of classical poetry, though he was sometimes troubled by the fact that it was written by non-Christians.

The York school was renowned as a center of learning not only in religious matters but also in the liberal arts, literature and science named the seven liberal arts. It was from here that Alcuin drew inspiration for the school he would lead at the Frankish court. He revived the school with disciplines such as the trivium and the quadrivium. Two codices were written, by himself on the trivium, and by his student Hraban.

Alcuin graduated from student to teacher sometime in the 750s. His ascendancy to the headship of the York school began after Aelbert became Archbishop of York in 767. Around the same time Alcuin became a deacon in the church. He was never ordained as a priest and there is no real evidence that he became an actual monk, but he lived his life like one.

In 781, King Elfwald sent Alcuin to Rome to petition the Pope for official confirmation of York’s status as an archbishopric and to confirm the election of a new archbishop, Eanbald I. It was then, on his way home, that Alcuin met Charles, king of the Franks.

Alcuin was reluctantly persuaded to join Charles's court. His love of the church and his intellectual curiosity made the offer one that he could not refuse. He was to join an already illustrious group of scholars that Charles had gathered around him like Peter of Pisa, Paulinus, Rado, and Abbot Fulrad. He would later write that "the Lord was calling me to the service of King Charles."

Alcuin was welcomed at the Palace School of Charlemagne. The school had been founded under the king’s ancestors as a place for educating the royal children, mostly in manners and the ways of the court. However, King Charles wanted more than this – he wanted to include the liberal arts and, most importantly, the study of the religion that he held sacred. From 782 to 790, Alcuin had as pupils the Charlemagne himself, his sons Pepin and Louis, the young men sent for their education to the court, and the young clerics attached to the palace chapel. Bringing with him from York his assistants Pyttel, Sigewulf, and Joseph, Alcuin revolutionized the educational standards of the Palace School, introducing Charlemagne to the liberal arts and creating a personalized atmosphere of scholarship and learning to the extent that the institution came to be known as the "school of Master Albinus."

Charlemagne was master at gathering the best men of every nation in his court. He himself became far more than just the king at the center. It seems that Charlemagne made many of these men his closest friends and counselors. They referred to him as "David," a reference to the Biblical King David. Alcuin soon found himself on intimate terms with the king and with the other men at court to whom he gave nicknames to be used for work and play. Alcuin himself was known as "Albinus" or "Flaccus." Like many of his learned contemporaries, Alcuin was an astrologer. David Berlinski, author of The Secrets of the Vaulted Sky: Astrology and the Art of Prediction (ISBN 0-15-100527-3) writes: "The ninth-century philosopher Alcuin, his voyages to the Middle East now abrogated, was an astrological adept, and it is widely claimed that he taught Charlemagne the principles of classical astrology" (pg. 116, 2003).

Alcuin’s friendships also extended to the ladies of the court, especially the queen mother and the daughters of the king. His relationships with these women, however, never reached the intense level of those with the men around him.

In 790, Alcuin went back to England, to which he had always been greatly attached. He dwelt there for some time, but Charlemagne then invited him back to help in the fight against the Adoptionist heresy which was at that time making great progress in Toledo, Spain, the old capital town of the Visigoths and still a major city for the Christians under Islamic rule in Spain. He is believed to have had contacts with Beatus of Liébana, from the Kingdom of Asturias, who fought against Adoptionism. At the Council of Frankfurt in 794, Alcuin upheld the orthodox doctrine, and obtained the condemnation of the heresiarch Felix of Urgel.

Having failed during his stay in England to influence King Aethelraed of Northumbria in the conduct of his reign, Alcuin never returned to live in England. Alcuin was back at Charlemagne's court by at least mid 792, writing a series of letters to Aethelraed of Northumbria, to Hygbald, Bishop of Lindisfarne, and Aethelheard, Archbishop of Canterbury in the succeeding months, which deal with the attack on Lindisfarne by Viking raiders in July 792. These letters, and Alcuin's poem on the subject De clade Lindisfarnensis monasterii provide the only significant contemporary account of these events.

In 796, Alcuin was in his sixties. He hoped to be free from court duties and was given the chance when Abbot Itherius of Saint Martin at Tours died. King Charles gave the abbey into Alcuin's care with the understanding that he should be available if the king ever needed his counsel.

As a Carolingian Renaissance figure

He made the abbey school into a model of excellence, and many students flocked to it; he had many manuscripts copied, the calligraphy of which is of outstanding beauty. He wrote many letters to his friends in England, to Arno, bishop of Salzburg, and above all to Charlemagne. These letters, of which 311 are extant, are filled mainly with pious meditations, but they further form a mine of information as to the literary and social conditions of the time, and are the most reliable authority for the history of humanism in the Carolingian age. He also trained the numerous monks of the abbey in piety, and it was in the midst of these pursuits that he died.

Alcuin died on May 19, 804, some ten years before the emperor. He was buried at St. Martin’s Church under an epitaph that partly read:

| “ | Dust, worms, and ashes now... Alcuin my name, wisdom I always loved, Pray, reader, for my soul. |

” |

Legacy

Alcuin is the most prominent figure of the Carolingian Renaissance, in which three main periods have been distinguished: in the first of these, up to the arrival of Alcuin at the court, the Italians occupy the central place; in the second, Alcuin and the Anglo-Saxons are dominant; in the third, which begins in 804, the influence of Theodulf the Visigoth is preponderant.

We owe to him, too, some manuals used in his educational work; a grammar and works on rhetoric and dialectics. They are written in the form of dialogues, and in the two last the interlocutors are Charlemagne and Alcuin. He also wrote several theological treatises: a De fide Trinitatis, commentaries on the Bible, etc.

Alcuin transmitted to the Franks the knowledge of Latin culture which had existed in England. We still have a number of his works. His letters have already been mentioned; his poetry is equally interesting. Besides some graceful epistles in the style of Fortunatus, he wrote some long poems, and notably a whole history in verse of the church at York: Versus de patribus, regibus et sanctis Eboracensis ecclesiae.

Alcuin was an advocate on behalf of freedom of conscience. As chief adviser to Charles the Great, he bravely tackled the emperor over his policy of forcing pagans to be baptized on pain of death. He argued, “Faith is a free act of the will, not a forced act. We must appeal to the conscience, not compel it by violence. You can force people to be baptized, but you cannot force them to believe.” His arguments prevailed; Charlemagne abolished the death penalty for paganism in 797. (Needham, Dr. N.R., Two Thousand Years of Christ’s Power, Part Two: The Middle Ages, Grace Publications, 2000, page 52.)

Alcuin College, part of the University of York, is named after him. The Alcuin Society brings together lovers of books and awards an annual prize for excellence in book design.

Further reading

- Allot, Stephen. Alcuin of York, his life and letters, William Sessions Limited, 1974. ISBN 0-900657-21-9

- Ganshof, F.L. The Carolingians and the Frankish Monarchy, Longman, 1971. ISBN 0-582-48227-5

- McGuire, Brian P. Friendship, and Community: The Monastic Experience, Cistercian Publications, 2000. ISBN 0-87907-895-2

- West, Andrew Fleming. Alcuin and the Rise of the Christian Schools, Greenwood Press, 1969. ISBN 0-8371-1635-X

External links

- John J. O'Connor and Edmund F. Robertson. Alcuin at the MacTutor archive

- Alcuin's book, Problems for the Quickening of the Minds of the Young - Retrieved September 19, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.