AIDS

AIDS is an acronym for Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome. It is thought to have originated in sub-Saharan Africa during the twentieth century and is now a global pandemic. AIDS is a collection of symptoms and opportunistic infections resulting from the depletion of the immune system caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus or HIV.

The virus that causes AIDS is transmitted through sexual relationships, by sharing contaminated needles, through blood transfusions, mishandling contaminated blood as well as during pregnancy, childbirth and breastfeeding. But, primarily HIV is transmitted through sexual relationships with an infected partner. Therefore, HIV/AIDS is both a medical and a moral concern. Effective prevention strategies need to take into account both dimensions of the disease.

Global epidemic

The Joint United Nations Programme of HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that 40.3 million people (between 36.7 and 45.3 million people) around the world were living with HIV in December 2005 including 2.3 million children. [2]. It was estimated that during 2005, between 4.9 and 6.6 million people were newly infected with HIV and between 3.1 and 3.6 million people with AIDS died. The number of new infections is still far out-pacing the number of deaths and “the AIDS epidemic continues to outstrip global efforts to contain it” (UNAIDS_and_WHO, 2005).

Sub-Saharan Africa remains by far the worst-affected region, with approximately 25.8 million people living with HIV at the end of 2005. Two thirds of all people living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa, as are 77 percent of all women with HIV. South & South East Asia are the second most affected regions with about 18.4 percent of the total number of people living with HIV (approximately 7.4 million people).

| World region | Estimated adult prevalence of HIV infection (ages 15–49) |

Estimated adult and child deaths during 2005 |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 6.6% to 8.0% | 2.1 to 2.7 million |

| Caribbean | 1.1% to 2.7% | 16,000 to 40,000 |

| South and South-East Asia | 0.4% to 1.0% | 290,000 to 740,000 |

| East Asia | 0.05% to 0.2% | 20,000 to 68,000 |

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | 0.6% to 1.3% | 39,000 to 91,000 |

| Latin America | 0.5% to 0.8% | 52,000 to 86,000 |

| Oceania | 0.2% to 0.7% | 1,700 to 8,200 |

| North Africa and Middle East | 0.1% to 0.7% | 25,000 to 145,000 |

| North America | 0.4% to 1.1% | 9,000 to 30,000 |

| Western Europe and Central Europe | 0.2% to 0.4% | less than 15,000 |

Source: UNAIDS and the WHO 2005 estimates. The ranges define the boundaries within which the actual numbers lie, based on the best available information. [3]

Origin

The official date for the beginning of the AIDS epidemic is marked as June 18, 1981, when the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention reported a cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (now classified as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia) in five gay men in Los Angeles in the early 1980s. [4] Originally dubbed GRID, or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, health authorities soon realized that nearly half of the people identified with the syndrome were not gay. Reporter Randy Shilts discovered the name of an extremely sexually active man, Gaëtan Dugas, who epidemiologists at the time suspected to be the first carrier of what was first called "gay-plague", but later research failed to track the epidemic to any individual carrier. [5] In 1982, the CDC introduced the term AIDS to describe the newly recognized syndrome.

Three of the earliest known instances of HIV infection are as follows:

- A plasma sample taken in 1959 from an adult male living in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

- HIV found in tissue samples from an American teenager who died in St. Louis in 1969.

- HIV found in tissue samples from a Norwegian sailor who died around 1976.

Two species of HIV infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is more virulent and more easily transmitted. HIV-1 is the source of the majority of HIV infections throughout the world, while HIV-2 is less easily transmitted and is largely confined to West Africa. [6] Both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are of primate origin. The origin of HIV-1 is the Central Common Chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes troglodytes). The origin of HIV-2 has been established to be the Sooty Mangabey, an Old World monkey of Guinea Bissau, Gabon, and Cameroon.

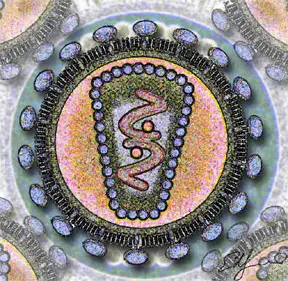

HIV

}}

Human immunodeficiency virus, commonly known by the initialism HIV, is a retrovirus that primarily infects vital components of the human immune system such as CD4+ T cells, macrophages and dendritic cells. It also directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells. As CD4+ T cells are required for the proper functioning of the immune system, when enough CD4+ T cells have been destroyed by HIV, the immune system functions poorly, leading to the syndrome known as AIDS. HIV also directly attacks organs, such as the kidneys, the heart and the brain leading to acute renal failure, cardiomyopathy, dementia and encephalopathy. Many of the problems faced by people infected with HIV result from failure of the immune system to protect from opportunistic infections and cancers.

Introduction of HIV

In 1983, scientists led by Luc Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute in France first discovered the virus that causes AIDS (Barré-Sinoussi et al., 1983). They called it lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV). A year later a team led by Robert Gallo of the United States confirmed the discovery of the virus, but they renamed it human T lymphotropic virus type III (HTLV-III) (Popovic et al., 1984). The dual discovery led to considerable scientific fall-out, and it was not until President Mitterand of France and President Reagan of the USA met that the major issues were ironed out. In 1986, both the French and the US names were dropped in favour of the new term human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Coffin, 1986).

HIV is a member of the genus lentivirus (ICTVdb, 61.0.6), part of the family of retroviridae (ICTVdb, 61). Lentiviruses have many common morphologies and biological properties. Many species are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long duration illnesses associated with a long period of incubation (Lévy, 1993). Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon infection of the target-cell, the viral RNA genome is converted to double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase which is present in the virus particle. This viral DNA is then integrated into the cellular DNA for replication using cellular machinery. Once the virus enters the cell, two pathways are possible: either the virus becomes latent and the infected cell continues to function or the virus becomes active, replicates and a large number of virus particles are liberated which can infect other cells.

Two species of HIV infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the more virulent and easily transmitted, and is the source of the majority of HIV infections throughout the world; HIV-2 is largely confined to west Africa (Reeves and Doms, 2002). Both species originated in west and central Africa, jumping from primates to humans in a process known as zoonosis. HIV-1 has evolved from a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIVcpz) found in the chimpanzee subspecies, Pan troglodytes troglodytes (Gao et al., 1999). HIV-2 crossed species from a different strain of SIV, found in sooty mangabey monkeys in Guinea-Bissau (Reeves and Doms, 2002).

Symptoms

Early symptoms

When first infected by HIV, most people will not have any symptoms. Within a month or two, a flu-like illness may appear, accompanied by fever, headache, tiredness, and/or enlarged lymph nodes. Usually these symptoms disappear within a week to a month, but during this period infected people are highly contagious.

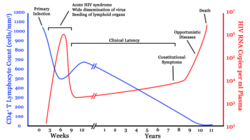

In most cases, HIV infections reduce the number of CD4 positive T (CD4+T) cells. These cells are our body’s main defense against infections and, without treatment, HIV slowly destroys these T-cells. When the T-cell count falls below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood, an HIV infected person is said to have ‘contracted’ AIDS. In a healthy adult the T-cell count is usually 1,000 or more.

- Infection with HIV-1 is associated with a progressive loss of CD4+ T-cells. This rate of loss can be measured and is used to determine the stage of infection. The loss of CD4+ T-cells is linked with an increase in viral load. The clinical course of HIV-infection generally includes three stages: primary infection, clinical latency and AIDS (Figure 1). HIV plasma levels during all stages of infection range from just 50 to 11 million virions per ml (Piatak et al., 1993).

Severe and persistent symptoms may not appear for more than 10 years. This “asymptomatic” period varies widely in duration between individuals. As complications begin to set in, the lymph nodes enlarge. This may last for more than three months and be accompanied with other symptoms including: loss of weight and energy, frequent fevers and sweats, persistent or frequent yeast infections, skin rashes, and short-term memory loss. (HIV Infection and AIDS: An Overview, 2005)

AIDS symptoms

In people living with AIDS (PLWA), the immune system is so ravaged by HIV, that the body can no longer defend itself. Bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites and other opportunistic infections go almost unchecked. Common symptoms of PLWA include:

- Coughing and shortness of breath

- Seizures and lack of coordination

- Mental confusion and forgetfulness

- Persistent diarrhea

- Fever

- Vision loss

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weight loss and extreme fatigue

- Severe headaches

- Coma

Many PLWA become debilitated and cannot hold a job or do work at home. However, a small number of people infected with HIV never develop AIDS. They are being studied by scientists to determine why, although they have HIV, their infection has not progressed into AIDS. (HIV Infection and AIDS: An Overview, 2005)

Prevention

As with all diseases, prevention is better than cure. This is all the more true for HIV/AIDS because, although treatments exist that will slow the progression from HIV to AIDS, there is currently no known cure or vaccine.

The most effective method for preventing HIV/AIDS requires a two pronged approach: strengthening moral values for the general population and targeting high risk groups (sex traffickers, drug uses and those likely to engage in non-marital sex) with barrier devices such as condoms.

ABC Model

According to a report from the U.S. Agency for International Development, there is only one country in the world that has substantially turned back the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

- Uganda is the standout among countries that have effectively responded to HIV/AIDS under the guidance of national leadership in both the political and religious realms. Uganda has experienced the most significant decline in HIV prevalence of any country in the world. (Green, 2003)

Uganda’s model, developed indigenously, is called the “ABC model.” Here “A” stands for Abstinence, “B” for Be faithful, and “C” for Condoms (used correctly and consistently). Importantly, equal emphasis was not given to each component. Ugandans put the primary emphasis on “A” and “B,” all the while condom distribution continued through the Ministry of Health, under a “Policy of Silent Promotion” (Dyer, 2003).

The Vatican and other religious groups oppose the use of condoms. Nonetheless, having a dual approach to HIV/AIDS prevention allows both the faith-based organizations and the medical community to work towards a common goal. This ABC model made it possible for the faith-based communities to be fully engaged in HIV/AIDS prevention without violating their theologies. Religious groups focused on “A” and “B” while health care professionals focused on “C.” Both benefited from this specialization.

Religious communities have vast networks that reach into the most rural areas, they can be powerful agents for behavioral and social change, they have resources to mobilize large numbers of volunteers, and they have experience in health care and education. Their full participation in HIV/AIDS prevention was essential in Uganda’s success.

It was important that the condom message be specifically targeted and not mass marketed. Separating “A” and “B” from “C” helped the condom message be “very effective” (Green, et al., 2005) in high-risk groups. By having a well-defined small target, condom use could be more effectively monitored, including the needed education and training. Importantly, this small focus did not undermine the message to the general population that human sexuality should be an exclusive act of marriage.

Uganda’s model has been heavily scrutinized and well documented. In a generalized heterosexual population HIV prevalence declined nearly 70 percent since the early 1990s. Importantly, it was accompanied with a 60 percent reduction in casual sex. The decline of HIV prevalence in 15- to 19-year-olds was 75 percent and was seen as a key to Uganda’s success. The annual cost was $1 per person aged 15 and above. If this ABC program been implemented throughout sub-Saharan Africa by 1996, it is estimated that there would be 6 million fewer persons infected with HIV and 4 million fewer children would have been orphaned (Green, et al., 2005).

CNN approach

Another widely used approach to HIV/AIDS prevention is the CNN Approach. This is:

- Condom use, for those who engage in risky behavior.

- Needles, use clean ones

- Negotiating skills; negotiating safer sex with a partner and empowering women to make smart choice

Thailand is seen as an example of a successful mass marketing strategy. Starting in the early 1990s, the Thai government implemented a tough policy which mandated condom use for all commercial sex workers. However, there was another behavior change working in tandem with the strong push from the government. The decline in HIV/AIDS in Thailand had two contributing factors: increased condom usage and the reduction in the number of sex partners. There was “a 60% decline in visits to sex workers” and “the proportion of men reporting casual sex during the past 12 months declined 46 percent, from 28 percent in 1990 to 15 percent in 1993.” (Green, et al., 2005)

Mother to child transmission

There is a 15–30% risk of transmission of HIV from mother to child during pregnancy, labor and delivery. A number of factors influence the risk of infection, particularly the viral load of the mother at birth (the higher the load, the higher the risk). Breastfeeding increases the risk of transmission by 10–15%. This risk depends on clinical factors and may vary according to the pattern and duration of breastfeeding.

Studies have shown that antiretroviral drugs, cesarean delivery and formula feeding reduce the chance of transmission of HIV from mother to child. (Sperlin et al., 1996)

When replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable and safe, HIV-infected mothers are recommended to avoid breast feeding their infant. Otherwise, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life and should be discontinued as soon as possible. [7]

Treatment

There is currently no cure or vaccine for HIV or AIDS.

The optimal treatment consists of a combination ("cocktail") consisting of at least three drugs belonging to at least two types, or "classes," of anti-retroviral agents. Typical regimens consist of two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus either a protease inhibitor or a non nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). This treatment is frequently referred to as HAART (highly-active anti-retroviral therapy). [8]

Anti-retroviral treatments, along with medications intended to prevent AIDS-related opportunistic infections, have played a part in delaying complications associated with AIDS, reducing the symptoms of HIV infection, and extending patients' life spans. Over the past decade the success of these treatments in prolonging and improving the quality of life for people with AIDS has improved dramatically.

Side effects

HAART is beneficial. But there are side effects, some severe, associated with the use of antiviral drugs. When taken in the later stages of the disease, some of the nucleoside RT inhibitors may cause a decrease of red or white blood cells. Some may also cause inflammation of the pancreas and painful nerve damage. There have been reports of complications and other severe reactions, including death, to some of the antiretroviral nucleoside analogs when used alone or in combination. Therefore, health care experts recommend that you be routinely seen and followed by your health care provider if you are on antiretroviral therapy.

The most common side effects associated with protease inhibitors include nausea, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In addition, protease inhibitors can interact with other drugs resulting in serious side effects. Fuzeon may also cause severe allergic reactions such as pneumonia, trouble breathing, chills and fever, skin rash, blood in urine, vomiting, and low blood pressure. Local skin reactions are also possible since it is given as an injection underneath the skin.

If you are taking HIV drugs, you should contact your health care provider immediately if you have any of these symptoms.

Transmission and infection

Patterns of HIV transmission vary in different parts of the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for an estimated 60% of new HIV infections worldwide, controversy rages over the respective contribution of medical procedures, heterosexual sex and the bush meat trade. In the United States, sex between men (35%) and needle sharing by intravenous drug users (15%) remain prominent sources of new HIV infections. [9] In January 2005, Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of NIAID said, "Individual risk of acquiring HIV and experiencing rapid disease progression is not uniform within populations". NIH press release Some epidemiological models suggest that over half of HIV transmission occurs in the weeks following primary HIV infection before antibodies to the virus are produced. [10] [11] Investigators have shown that viral loads are highest in semen and blood in the weeks before antibodies develop and estimated that the likelihood of sexual transmission from a given man to a given woman would be increased about 20-fold during primary HIV infection as compared with the same couple having the same sex act 4 months later. [12] Most people who are infected typically suffer from days to weeks of fever with or without muscle and joint aches, fatigue, headache, sore throat, swollen glands and sometimes rash. This "acute retroviral syndrome" is rarely diagnosed because it is difficult to distinguish from other very common ailments.

The Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in the United States reported a cluster of HIV infections in 13 of 42 young women who reported sexual contact with the same HIV infected man in a rural county in upstate New York between February and September 1996 [13]

The risk of oral sex has always been controversial. [14] Most of the early AIDS cases could be attributed to anal sex or vaginal sex. As the use of condoms became more widespread, there were reports of AIDS acquired by oral sex. [15] Unprotected oral sex is widely understood to be less risky than unprotected vaginal sex, which in turn is less risky than unprotected anal sex.

Heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 depends on the infectiousness of the index case and the susceptibility of the uninfected partner. Infectivity seems to vary during the course of illness and is not constant between individuals. Each 10 fold increment of seminal HIV RNA is associated with an 81% increased rate of HIV transmission. [16] During 2003 in the United States, 19% of new infections were attributed to heterosexual transmission [17]

The argument about the exact incidence of HIV transmission per act of intercourse is academic. Infectivity depends critically on social, cultural, and political factors as well as the biological activity of the agent. Whether the epidemic grows or slows depends on infectivity plus two other variables: the duration of infectiousness and the average rate at which susceptible people change sexual partners. [18]

Genetic susceptibility

CDC has released findings that genes influence susceptibility to HIV infection and progression to AIDS. HIV enters cells through an interaction with both CD4 and a chemokine receptor of the 7 Tm family. They first reviewed the role of genes in encoding chemokine receptors (CCR5 and CCR2) and chemokines (SDF-1). While CCR5 has multiple variants in its coding region, the deletion of a 32-bp segment results in a nonfunctional receptor, thus preventing HIV entry; two copies of this gene provide strong protection against HIV infection, although the protection is not absolute. This gene is found in up to 20% of Europeans but is rare in Africans and Asians; researchers and scientists believe that HIV had a similar viral shell as the bacteria which caused the black plague (1347-1350), leading to the decimation of one-third of the European population, possibly explaining why the CCR5-32 receptor gene is more prevalent in Europeans than Africans and Asians. Multiple studies of HIV-infected persons have shown that presence of one copy of this gene delays progression to the condition of AIDS by about 2 years. And it is possible that a person with the CCR5-32 receptor gene will not develop AIDS, although they will still carry HIV.

Template:AIDS

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Because of their length, the list of references used in developing this article are at AIDS/references

- Dyer, Emilie. (2003). And Banana Trees Provided the Shade. Kampala, Uganda: Ugandan AIDS Commission.

- Green, Edward C. (2003). Faith-Based Organizations: Contributions to HIV Prevention. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, The Synergy Project.

- Green, Edward C., Rand L. Stoneburner, Daniel Low-Beer, Norman Hearst and Sanny Chen. (2005). Evidence That Demands Action: Comparing Risk Avoidance and Risk Reduction Strategies for HIV Prevention. Austin, TX: The Medical Institute.

- HIV Infection and AIDS: An Overview. (2005, March). Washington, DC: Courtesy: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Retrieved Jan. 24, 2006, from http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/hivinf.htm.

- UNAIDS_and_WHO. (2005, December). AIDS epidemic update: December 2005. Joint United Nations Programme of HIV/AIDS and the World Health Organization. Retrieved January, from http://www.unaids.org/epi/2005/doc/EPIupdate2005_pdf_en/epi-update2005_en.pdf.

- Barré-Sinoussi, F., Chermann, J. C., Rey, F., Nugeyre, M. T., Chamaret, S., Gruest, J., Dauguet, C., Axler-Blin, C., Vezinet-Brun, F., Rouzioux, C., Rozenbaum, W. and Montagnier, L. (1983) Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science 220, 868-871 PMID 6189183

- Carr, J. K., Foley, B. T., Leitner, T., Salminen, M., Korber, B. and McCutchan, F. (1998) Reference Sequences Representing the Principal Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 in the Pandemic. In: Los Alamos National Laboratory (Ed) HIV Sequence Compendium, pp. 10-19

- Chan, D. C. and Kim, P. S. (1998) HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93, 681-684 PMID 9630213

- Coakley, E., Petropoulos, C. J. and Whitcomb, J. M. (2005) Assessing chemokine co-receptor usage in HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 18, 9-15. PMID 15647694

- Coffin, J., Haase, A., Levy, J. A., Montagnier, L., Oroszlan, S., Teich, N., Temin, H., Toyoshima, K., Varmus, H., Vogt, P. and Weiss, R. A. (1986) What to call the AIDS virus? Nature 321, 10. PMID 3010128.

- Gao, F., Bailes, E., Robertson, D. L., Chen, Y., Rodenburg, C. M., Michael, S. F., Cummins, L. B., Arthur, L. O., Peeters, M., Shaw, G. M., Sharp, P. M. and Hahn, B. H. (1999) Origin of HIV-1 in the chimpanzee Pantroglodytes troglodytes. Nature 397, 436-441 PMID 9989410

- Gelderblom, H. R. (1997) Fine structure of HIV and SIV. In: Los Alamos National Laboratory (Ed) HIV Sequence Compendium, 31-44.

- Gendelman, H. E., Phelps, W., Feigenbaum, L., Ostrove, J. M., Adachi, A., Howley, P. M., Khoury, G., Ginsberg, H. S. and Martin, M. A. (1986) Transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat sequences by DNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83, 9759-9763 PMID 2432602

- ICTVdB Descriptions. 61.0.6. Lentiviruses.

- ICTVdB Descriptions. 61. Retroviridae.

- Kahn, J. O. and Walker, B. D. (1998) Acute Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med 331, 33-39 PMID 9647878.

- Knight, S. C., Macatonia, S. E. and Patterson, S. (1990) HIV I infection of dendritic cells. Int Rev Immunol. 6,163-75 PMID 2152500

- Lévy, J. A. (1993) HIV pathogenesis and long-term survival. AIDS 7, 1401-1410 PMID 8280406

- Osmanov, S., Pattou, C., Walker, N., Schwardlander, B., Esparza, J. and the WHO-UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. (2002) Estimated global distribution and regional spread of HIV-1 genetic subtypes in the year 2000. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 29, 184-190 PMID 11832690

- Piatak, M., Jr, Saag, M. S., Yang, L. C., Clark, S. J., Kappes, J. C., Luk, K. C., Hahn, B. H., Shaw, G. M. and Lifson, J.D. (1993) High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR. Science 259, 1749-1754 PMID 8096089

- Pollard, V. W. and Malim, M. H. (1998) The HIV-1 Rev protein. Annu Rev Microbiol. 52, 491-532 PMID 9891806

- Popovic, M., Sarngadharan, M. G., Read, E. and Gallo, R. C. (1984) Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science 224, 497-500 PMID 6200935

- Reeves, J. D. and Doms, R. W. (2002) Human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J. Gen. Virol. 83, 1253-1265 PMID 12029140

- Siegfried N, Muller M, Deeks J, Volmink J, Egger M, Low N, Walker S, Williamson P. (2005) HIV and male circumcision—a systematic review with assessment of the quality of studies. Lancet Infect Dis 5, 165-173 PMID 15766651

- Tang, J. and Kaslow, R. A. (2003) The impact of host genetics on HIV infection and disease progression in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 17, S51-S60 PMID 15080180

- Thomson, M. M., Perez-Alvarez, L. and Najera, R. (2002) Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 genetic forms and its significance for vaccine development and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2, 461-71 PMID 12150845

- UNAIDS How can HIV be transmitted

- UNAIDS (2004) AIDS epidemic update December 2004

- WHO (2005) 26 July WHO/UNAIDS statement on South African trial findings regarding male circumcision and HIV

- Wyatt, R. and Sodroski, J. (1998) The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280, 1884-1888 PMID 9632381

- Zheng, Y. H., Lovsin, N. and Peterlin, B. M. (2005) Newly identified host factors modulate HIV replication. Immunol Lett. 97, 225-234 PMID 15752562

External links

- AIDS.ORG AIDS.ORG: Educating - Raising HIV Awareness - Building Community

- AIDSinfo 2002 The Glossary of HIV/AIDS-Related Terms 4th Edition

- AIDSmeds.com 2005 AIDSmeds.com: Comprehensive lessons on HIV/AIDS and their treatments

- Center for Disease Control (2005). Divisions of HIV/AIDS Prevention

- Health Action AIDS 2003 HIV Transmission in the Medical Setting

- NIAID/NIH 2003 Basic Information About AIDS and HIV

- NIAID/NIH 2003 Evidence That HIV causes AIDS

- NIAID/NIH 2004 How HIV Causes AIDS

- The Body 2005 The Body: The Complete HIV/AIDS Resource

- UNAIDS 2005 The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- Journal Watch 2005 AIDS Clinical Care

- UNAIDS Scenarios to 2025 Document regarding three scenarios for HIV/AIDS in Africa for the year 2025 (Large PDF file)

ar:متلازمة نقص المناعة المكتسب bg:СПИН bm:Sida bs:AIDS ca:SIDA cs:AIDS da:Aids de:Aids als:AIDS es:SIDA eo:Aidoso fa:ایدز fr:Syndrome d'immunodéficience acquise ko:에이즈 hi:एड्स he:איידס ku:AIDS lv:AIDS lt:AIDS hu:AIDS ms:AIDS nl:Aids ja:後天性免疫不全症候群 no:AIDS nn:HIV/AIDS pl:Zespół nabytego niedoboru odporności pt:Síndrome da imuno-deficiência adquirida qu:SIDA ru:СПИД sk:AIDS fi:AIDS sv:AIDS ta:எய்ட்ஸ் vi:AIDS tr:AIDS uk:СНІД zh:艾滋病 simple:AIDS

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.