Zhang Daoling

Zhang Daoling (ca. 34-156 C.E.)(张道陵; pinyin Zhāng Dàolíng, Wade-Giles Chang Tao-ling), also commonly called Zhang Ling, was a Daoist hermit who lived during the Eastern Han dynasty. Contrary to the antinomian/apolitical bent of many such renunciants, Zhang had a certain organizational genius, which was manifested in his founding of the theocratic and millennial Zhengyi Mengwei Tianshi Dao ("Tradition of the Celestial Master of the Mighty Commonwealth of Orthodox Oneness") sect (also known as the "Tianshi Dao" ("Way of the Celestial Masters") or the "Wudou Mi Dao" ("Five Pecks of Rice Movement"))—one of the earliest and most influential schools of institutional Daoism.

While few of the specifics of Zhang Daoling's life are definitively known, he remains a frequent player in Daoist and popular Chinese folklore, with tales describing both his earthly encounters with the divinized Laozi and his posthumous adventures as an immortal.

Biographical Sketch

- See also: Celestial Masters, Laozi, Yellow Turban Rebellion

Though little is definitively known about the life of Zhang Daoling, Chinese traditions of considerable antiquity offer glimpses into the details of his biography. He was born and raised in the province of Pei (modern Anhui/Kiangsi) in the first century of the Common Era (with traditional accounts placing the date of his birth at 34 C.E. and more skeptical sources listing it as 25 to 40 years later than that).[1][2] Though an intelligent youth, he was thoroughly influenced by his family's profound poverty, to the extent that he forswore any type of learning (i.e., traditional Confucian scholarship) that did not lead to the promise of immortality. To that end, he became a renunciant, abandoning family, friends, and mortal concerns in favor of private scholarship, meditation and alchemical practice. During his quest for immortality, he is reputed to have dwelt on various holy mountains and to have developed potent magical abilities as both a healer and an exorcist.[3]

Sometime during the first half of the second century, Zhang arrived in Sichuan province, where his intense personal charisma and purported spiritual abilities guaranteed a warm reception among the province's residents.[4] While there, he allegedly received a revelation from the divinized Laozi (Taishang Laojun), who provided him with the plan for a theocratic state, as well as a catalog of new religious practices, a divinely revealed scripture (describing the first authoritatively Daoist pantheon), and an arsenal of magico-spiritual tools for combating the forces of evil (ca. 142 C.E.).[5] After receiving this revelation (which is described in more detail below), he and a contingent of landowners (many of whom had been healed of their illnesses by Zhang) ensconced themselves in the mountains of their province and established a theocratic state:

- Their T'ai-shang Lao-chun [the apotheosized Laozi) was a celestial god who installed Chang Tao-ling as his terrestrial representative, a religious function which, as far as the secular reign is concerned, was merely intended to secure the interregnum until a new virtuous dynasty, worthy of the god's approval, would have succeeded to the Han and assumed political authority over the Taoist parishes of Szechwan.[6]

In addition to the Master's reputation for spiritual ability, his personal ethics (and those of the community that he founded) were instrumental to the movement's success. For instance, he banned the practice of animal sacrifice[7] and encouraged the confession of sins as a potent cure for various ailments.[8] Most influentially, he advocated a policy of redistributive ethics that required the financially able members of the congregation to pay a tithe of five pecks of rice for their participation, and then used these revenues to pay for the administration of the community and the care of its less fortunate members. He was aided in these tasks by a hierarchy of twenty-four "libationers" who each administered one of the districts in their kingdom's demesnes. After the foundation of this society, Zhang ruled over it for fifteen years before his death in 157 C.E.[9]

The piety and influence of Zhang Daoling have long been acknowledged throughout the Chinese socio-cultural sphere, to the extent that Emperor Taiwu Ti (r. 424-452) posthumously honored the Taoist sage by bestowing the title Tian Shi ("Heavenly Master") upon him. Since then, this is the moniker that the sect most often uses when describing themselves.[10]

Mythological and Religious Accounts

The Hierophany of Laozi

As mentioned above, the Celestial Masters aver that Laozi himself (in his apotheosized form) appeared to Zhang Daoling on Mount Heming, Sichuan, informing the hermit that the present social order was coming to an end and that it would be followed by an era of Great Peace. As a result, it was necessary for Zhang to establish a judicious and moral kingdom that would be able to usher in this joyous, millennial era:

Church founder Zhang Daoling's original vision was of Laozi, depicted in Daoist texts of the Han and Six Dynasties periods as a god who descends, messiah-like, at various critical points in China's history, generally to assist a sage-king to found a new dynasty. The crisis of the Han decline was described as a fall from a past golden age ("high antiquity") to the current disheartening state ("low antiquity"), an era when the "stale emanations of the six heavens" had supplanted the originally pure heavenly breaths. Celestial Masters adepts were characterized as "seed people," a Daoist elect saved through the good works of the Celestial Masters church, who would in turn repopulate a new world purged by the disasters of the "stale breaths." If the primary emphasis among early Celestial Masters was on church building and religious practice, it is nonetheless obvious that the elements of discourse were in place to permit an evolution toward a more stridently apocalyptic stance.[11][12]

To aid the hermit in achieving these goals, Laozi bequeathed numerous secrets and relics to him, including a revolutionary new scripture, various exorcistic techniques, and a demon vanquishing sword.

Fabulous Events in Zhang's Biography

In addition to the more credible events in Zhang Daoling's life story, the various tellings also include numerous references to the supramundane. For instance, virtually all versions suggest that the hermit discovered an elixir of immortality during one of his solitary sojourns in the mountains. In fact, one suggests that he did not wish to depart the physical world immediately, so he only consumed one half of the elixir—a choice that granted him numerous supernatural abilities, such as flight and co-location.[13] In another account, he was only able to achieve his earthly domain in Sichuan province after having bested all of their demons in spiritual and physical combat:

- After going through a thousand days of discipline, and receiving instructions from a certain goddess called Yünü, who taught him to walk among the stars, he proceeded to fight with the king of the demons, to divide mountains and seas, and to command the wind and thunder to come and go. All the demons fled before him, leaving not a trace of their retreating footsteps. On account of the prodigious slaughter of demons by this hero, the wind and thunder were reduced to subjection, and various divinities came with eager haste to acknowledge their faults.[14]

At the end of his life, it is thought that he rose bodily into the heavens and became an immortal.[15]

Zhang Daoling in Religious Practice

Zhang Daoling, in the guise of Zhang Tianshi, is a popular deity throughout the East Asian cultural sphere, where he is esteemed for his exorcistic abilities. These devotions are well summarized by Anne Goodrich:

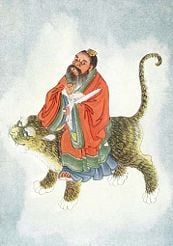

T'ien-shih [Tianshi in pinyin] is one of the most potent of exorcists. His picture or even the imprint of his seal, hung in the home, will protect it from all evil spirits. His charms will drive away, and keep away the demons of illness. He is prayed to in times of trouble. There are a number of special days to make petitions and offerings: the 28th of the 4th moon, the 15th day of the 1st month, and the 15th day of the 2nd month which is the birthday of T'ai-shang Lao-chün [the divinized Laozi). … He is portrayed as an old man in a scholar's gown, wearing a Taoist crown, … [and is often also] portrayed riding on the back of a tiger brandishing his sword.[16]

Further, Daoist adepts still trace their lineages back to Zhang Daoling, an unbroken line of succession that is now headquartered in Taiwan (following the Communist rise to power in 1949).[17][18]

Notes

- ↑ Howard S. Levy, "Yellow Turban Religion and Rebellion at the End of Han." Journal of the American Oriental Society 76(4) (October-December 1956: 215

- ↑ E.T.C. Werner ,"Jade Emperor" in A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology. (Wakefield, NH: Longwood Academic, 1990), 38.

- ↑ Werner, 38.

- ↑ Anna Seidel, "The Image of the Perfect Ruler in Early Taoist Messianism: Lao-tzu and Li Hung." History of Religions 9(2/3) (November 1969 - February 1970): 231.

- ↑ Isabella Robinet. Taoism: Growth of a Religion. (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997 (original French 1992), 55.

- ↑ Seidel (1969-1970), 227. Ownby provides a similar description: Zhang was a faith healer, visionary, and religious innovator who founded a Daoist church-the Way of the Celestial Masters-in western China during the waning years of the Han dynasty, following a religious vision he experienced in 142 C.E. The church functioned as a genuine theocracy, filling the void created by the fall of the Han and enrolling hundreds of thousands of members over several decades" 1517.

- ↑ Jeaneane Fowler. An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism. (Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press, 2005), 138.

- ↑ This development is outlined by Poo: "At the end of the Han dynasty in the late 2nd century C.E., the Five Pecks of Rice Sect founded by the Taoist Master Chang Taoling required its adepts to stay in a quiet room to repent for their wrong doings if they were caught by sickness. Yet this seemingly moral element in the early Taoist religion was not connected with the way to immortality. One of the earliest Taoist scriptures the T'ai P'ing Ching contains various moral advice to its readers, yet only rarely did these have to do with immortality" 18. See also Reiter: "though not directly tied to the pursuit of immortality, a major development pioneered by Zhang Daoling was the equation between guilt and sin (on one hand) and corporeal health and good fortune (on the other)" 352.

- ↑ Fowler, 139; Levy, 215-217; Werner, 38.

- ↑ Werner, 37.

- ↑ David Ownby, "Chinese Millenarian Traditions: The Formative Age." The American Historical Review 104(5) (December 1999): 1518

- ↑ See also Seidel (1984): "They believed that the Tao had manifested itself in the guise of Lao tzu, down through the ages, to teach the culture heroes of antiquity and to save mankind from the periodic cataclysms brought about by benighted rulers incapable of worshipping and serving the Tao. Now, at the end of the Han, the god appears again, but not any more to advise an emperor but to appoint the leader of this popular movement, Chang Tao-ling, as his successor. He conferred on Chang Tao-ling the hereditary title "Celestial Master" and the priestly function to guide the people through the chaos of the age until a new virtuous dynasty-worthy of the god's approval would have succeeded to the Han." Anna Seidel, "Taoist Messianism." Numen 31 (Fascicle 2) (December 1984): 167.

- ↑ Werner, 38-40.

- ↑ Werner, 40.

- ↑ Fowler, 139; Levy, 215-217; Werner, 38.

- ↑ Anne S. Goodrich. Peking Paper Gods: A Look at Home Worship. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series XXIII. (Nettetal: Steyler-Verlag, 1991), 161 and ff. 197

- ↑ Goodrich, 310

- ↑ Michael R. Saso, "The Taoist Tradition in Taiwan," The China Quarterly 41 (January - March, 1970): 83-102. 84.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fowler, Jeaneane. An Introduction to the Philosophy and Religion of Taoism. Portland, OR: Sussex Academic Press, 2005. ISBN 1845190866

- Goodrich, Anne S. Peking Paper Gods: A Look at Home Worship. Monumenta Serica Monograph Series XXIII. Nettetal: Steyler-Verlag, 1991. ISBN 380500284X.

- Levy, Howard S. "Yellow Turban Religion and Rebellion at the End of Han." Journal of the American Oriental Society 76(4) (October-December 1956): 214-227.

- Ownby, David. "Chinese Millenarian Traditions: The Formative Age." The American Historical Review 104(5) (December 1999): 1513-1530.

- Poo, Mu-chou. "The Images of Immortals and Eminent Monks: Religious Mentality in Early Medieval China (4-6 c. A.D.)." Numen 42(2) (May 1995): 172-196.

- Reiter, Florian C. "Conditions, Ways and Means of Healing in the Perspective of the Chinese Taoist." Oriens 33 (1992): 348-362.

- Robinet, Isabelle. Taoism: Growth of a Religion. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997 [original French 1992]. ISBN 0804728399.

- Saso, Michael R. "The Taoist Tradition in Taiwan," The China Quarterly 41 (January - March, 1970): 83-102

- Schipper, Kristopher. The Taoist Body. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993 [original French version 1982]. ISBN 0520082249.

- Seidel, Anna. "The Image of the Perfect Ruler in Early Taoist Messianism: Lao-tzu and Li Hung." History of Religions 9(2/3) (November 1969 - February 1970): 216-247.

- Seidel, Anna. "Taoist Messianism." Numen 31 (Fascicle 2) (December 1984): 161-174.

- Shuhmacher, Stephan and Gert Woerner (eds.). The Encyclopedia of Eastern Philosophy and Religion: Buddhism, Hinduism, Taoism, Zen. Boston: Shambala, 1994. ISBN 0877739803.

- Werner, E.T.C. "Jade Emperor" in A Dictionary of Chinese Mythology. Wakefield, NH: Longwood Academic, 1990. 341-352. ISBN 0893410349.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.