Shogi

Shogi (将棋 shōgi), or Japanese chess, is the most popular of a family of chess variants native to Japan. Shogi is said to be derived from the game of chaturanga, played in ancient India, which became the ancestor of chess in the West. The game is played by two players using a board with a rectangular grid. Each player has a set of twenty-seven pieces including kings, rooks, a bishop, gold and silver generals, knights, lances, and pawns. The pieces are differentiated by size and by Chinese characters painted on their backs. Pieces which are captured from an opponent during play can be “dropped” into empty spaces on the board and rejoin the game as part of the attacker’s forces.

The oldest document referring to shogi dates from the tenth century. Numerous variants to the game were played, sometimes with additional pieces such as a “drunken elephant.” In 1612, the shogunate passed a law giving endowments to top players of shogi, and they became 'iemoto', taking on the hereditary title of Meijin. After the Meiji Restoration, the title of Meijin was no longer hereditary, but was instead conferred by recommendation. In 1935, the title of Meijin began to be conferred based on ability demonstrated at tournaments. Shogi players are ranked in a system of dan and kyu similar to that used in the martial arts.

The fact that the shogi pieces are differentiated with Chinese characters has impeded the spread of the game to other countries, but it has recently become popular in the Peoples Republic of China.

History of Shogi

Ancient Shogi

Arrival in Japan

Shogi is said to be derived from the game of chaturanga played in ancient India, which spread throughout the continent of Eurasia, developing into a variety of related games. In the West, it became chess, in China xiangqi (象棋), on the Korean Peninsula as janggi (장기), and in Thailand as makruk.

It is not clear when shogi was brought to Japan. There are tales relating that it was invented by Yuwen Yong of Northern Zhou, and that Kibi no Makibi (吉備真備) brought it back after visiting the country of Tang, but both these tales are likely to have been invented at the start of the Edo period by those keen to make a name for themselves as authorities on shogi.

There are several theories about when shogi spread to Japan, but the earliest plausible date is around the sixth century. It is thought that the pieces used in the shogi of the time were not the current five-sided pieces, but three-dimensional figures, as were used in chaturanga. However, pieces in this form have never been found.

Another theory gives a later date, stating that shogi was brought to Japan after the start of the Heian period. According to this theory, games such as xiangqi from China and janggi from Korea came to Japan at this time. Doubts remain about this theory because these games are different from shogi; for example, the pieces are placed on the intersections of lines instead of in the spaces. The game of makluk from South-East Asia was a possible influence, as there is a piece in this game which moves in the same way as the silver general, but it is not clear how the game could have been spread along the coast to Japan given the shipbuilding technology of the time.

Shogi in the Heian Period

One of the oldest documents indicating the existence of shogi is Kirinshō (麒麟抄), written by Fujiwara Yukinari (藤原行成) (972 - 1027), a seven-volume work which contains a description of how to write the characters used for shogi pieces, but the most generally accepted opinion is that this section was added by a writer from a later generation. Shin Saru Gakuki (新猿楽記) (1058 - 1064), written by Fujiwara Akihira also has passages relating to shogi, and is regarded as the earliest document on the subject.

The oldest archaeological evidence is a group of 16 shogi pieces excavated from the grounds of Kōfuku-ji in Nara Prefecture, and as a wooden plaque inscribed in the sixth year of Tenki (1058) was found at the same time, the pieces are thought to be of the same period. The pieces of the time appear to have been simple ones made by cutting a wooden plaque and writing directly on the surface, but they have the same five-sided shape as modern pieces. As "Shin Saru Gakuki", mentioned above, is of the same period, this find is backed up by documentary evidence.

The dictionary of common folk culture, Nichūreki (二中歴), estimated to have been created between 1210 and 1221, a collection based on the two works Shōchūreki (掌中歴) and Kaichūreki (懐中歴), thought to have been written by Miyoshi Tameyasu (三善為康), describes two forms of shogi, large (dai) shogi and small (shō) shogi. So as not to confuse these with later types of shogi, in modern times these are called Heian shogi (or Heian small shogi) and Heian dai shogi. Heian shogi is the version on which modern shogi is based, but it is written that one wins if one's opponent is reduced to a single king, apparently indicating that at the time there was no concept of pieces in the hand.

The pieces used in these variants of shogi consist of those used in Heian shogi, king, gold general, silver general, knight, lance and pawn, and those used only in Heian great shogi, the copper general, iron general, side mover , wild tiger, flying dragon, free chariot and go between. The names of the Heian shogi pieces correspond faithfully to those in Chaturanga (general, elephant, horse, chariot and soldier), and add above them Japanese characters representing the five treasures of Buddhism, (jewel, gold, silver, Katsura tree and aroma), according to a theory by Kōji Shimizu, chief researcher at the Archaeological Institute of Kashihara, Nara Prefecture. There is also a theory by Yoshinori Kimura that while Chaturanga was from the start a game simulating war, with pieces being discarded after capture, Heian shogi involved pieces kept in the hand.

The Development of Shogi

In games around the world related to shogi, the rules have changed with the passage of time, increasing the abilities of the pieces or their numbers as winning strategies have been discovered. The Japanese game of shogi is no exception to this.

Around the thirteenth century, the game of dai shogi, created by increasing the number of pieces in Heian shogi, was played, as was the game of sho shogi, which adds the rook, bishop and drunken elephant from dai shogi to Heian shogi. Around the fifteenth century, as the rules of dai shogi had become too complicated, they were simplified, creating the game of chu shogi, which is close to the modern game. It is thought that the rules of modern shogi were fixed in the sixteenth century, when the drunken elephant was removed from the set of pieces. According to Shoshōgi Zushiki (諸象戯図式), a set of shogi rules published in 1696, during the Genroku period, it states that the drunken elephant piece was removed from the game of sho shogi by Emperor Go-Nara during the Tenmon period (1532 - 1555), but whether or not this is true is not clear.

As many as 174 shogi pieces have been excavated from the Ichijōdani Asakura Family Historic Ruins, which are thought to be from the latter half of the 16th century. Most of these pieces are pawns, but there is also one drunken elephant, leading to the hypothesis that in this period variations of shogi with and without the drunken elephant existed side by side.

One point of note in the history of this family of games is that it was during this period that the unique rule in Japanese shogi was developed whereby captured pieces (pieces in the hand) could be returned to the board. It is thought that the rule of pieces in the hand was proposed around the sixteenth century, but there is also a theory that this rule existed from the time of Heian sho shogi.

In the Edo period, more types of shogi with yet more pieces were proposed. Tenjiku shogi, dai dai shogi, maka dai dai shogi, tai shogi (also called "dai shogi", but termed "tai shogi" to avoid confusing the two) and taikyoku shogi. However, it is thought that these forms of shogi were only played to a very limited extent.

Modern Shogi

Castle Shogi and the Iemotos

Modern shogi (hon shogi), like go, was officially approved by the Tokugawa shogunate. In 1612, the shogunate passed a law giving endowments to shogi players including Kanō Sansa (加納算砂), Hon'inbō Sansa (本因坊算砂) and Shūkei (宗桂) (who was given the name Ōhashi Shūkei, 橋宗桂 after his death). These iemotos (families upholding the tradition of shogi) gave themselves the title of go-dokoro (碁所, places of go) and shogi-dokoro (将棋所), places of shogi. The first O-hashi Shu-kei received fifty koku of rice and five men. In the Kan'ei period (around 1630), the "castle shogi" (御城将棋) tournament, where games were played before a shogun, was held. During the time of the eighth shogun, Tokugawa Yoshimune, an annual castle shogi tournament, held on the 17th day of Kannazuki, was established, and today the corresponding day in the modern calendar, November 17, has been designated Shogi Day.

The iemotos of shogi who were paid endowments were called Meijin (|名人). During the reign of the shogunate, the title of Meijin became a hereditary title of the Ōhashi family and one of its branches, and the Itō family. Today the title of Meijin is still used, for the winner of the Meijin-sen competition. It became a tradition for shogi players inheriting the title of Meijin to present a collection of shogi puzzles to the shogunate government.

A number of genius shogi players emerged who were not hereditary Meijin. Itō Kanju (伊藤看寿) was born in the mid-Edo period, and showed promise as a potential Meijin, but died young and never inherited the title (which was bestowed on him posthumously). Kanju was a skilled composer of shogi puzzles, and even today his collection of puzzles "Shogi Zukō" (将棋図巧) is known as one of the greatest works of its kind. In the late Edo period, Amano Sōho (天野宗歩) came to prominence. As he was one of the "Arino group" of amateur shogi players, the rank of meijin was out of his reach, but he was feared for his skill and said to have "the ability of a 13-dan player;" he was later termed a kisei (棋聖, wise man or master of shogi). Sōho is considered one of the greatest shogi players in history.

Newspaper Shogi and the Formation of Shogi Associations

After the fall of the Tokugawa shogunate, the three shogi families were no longer paid endowments, and the iemoto system in shogi lost its power. The hereditary lines of the three families ended, and the rank of Meijin came to be bestowed by recommendation. The popularity of amateur shogi continued in the Meiji period, with shogi tournaments and events held all over Japan, and so called "front-porch shogi" (縁台将棋) played wherever people gathered, in bath houses or barber's shops. However, it is thought that, with the exception of a handful of high-ranking players at the end of the nineteenth century, it was impossible to make a living as a professional shogi player during this period.

From around 1899, newspapers began to publish records of shogi matches, and high-ranking players formed alliances with the aim of having their games published. In 1909, the Shogi Association (将棋同盟社) was formed, and in 1924, the Tokyo Shogi Association (東京将棋同盟社) was formed, with Sekine Kinjirō (関根金次郎), a thirteenth-generation meijin, at its head. This was a predecessor of the modern Japan Shogi Association (日本将棋連盟) which takes 1924 as the date of its foundation.

Trends in Modern Shogi

The Ability-based Meijin System and Developments in Title Matches

In 1935, Sekine Kinjiro stepped down from the rank of Meijin, which then came to be conferred based on ability as demonstrated during short term performance, rather than on recommendation. The shogi title matches began with the first Meijin title match (名人戦, meijin-sen), (known officially at the time as the Meijin Kettei Kisen (人決定大棋戦)), which was held over two years, with Yoshio Kimura (木村義雄) becoming the first Meijin in 1937.

Later, in 1950, the Kudan title match (九段戦, kudan-sen, 9-dan title match) (renamed the Jūdan title match, 十段戦, jūdan-sen (10-dan title match) in 1962) was founded, followed by the Ōshō title match (王将戦, ōshō-sen, King title match) in 1953. Initially, the Ōshō-sen was not an official title match, but it became one in 1983. In 1960 the Ōi title match (王位戦) ōi-sen was founded, and later the Kisei-sen (棋聖戦) in 1962, and the Kiō|棋王戦|kiō-sen in 1974. The Jūdan-sen became the Ryūō title match (竜王戦, ryūō-sen) in 1988, completing the modern line-up of seven title matches.

Ōyama and Habu

It was considered to be nearly impossible to hold all the titles at once, but in 1957, Kōzō Masuda took all three of the titles which existed at the time (Meijin, Kudan and Ōshō), to become a triple champion (三冠王). Yasuharu Ōyama (大山康晴) later took these three titles from Masuda, and went on in 1959 to take the newly founded titles of Ōi and Kisei, becoming a quintuple champion (五冠王). Ōyama defended these titles for six years, a golden age which became known as the "Ōyama age". Ōyama reached a total of 80 title holding periods, an unprecedented achievement at the time, when there were fewer titles than at present.

After the number of titles increased to seven in 1983, it was believed to be impossible to hold all of them at once, but in 1996, Yoshiharu Habu became the first septuple champion (七冠王), beginning an age known as the "Habu age". Since then, there has never been a time when he was without a title, and he has amassed a total of over 60 title holding periods.

Women’s Shogi

While there are both men and women among the ranks of professional shogi players, no woman player has yet won through the pro qualifier leagues (新進棋士奨励会, shinshin kishi shōreikai) to become an officially certified professional player (棋士, kishi). This inhibited the spread of the game among women, and to overcome the problem, the system of professional woman shogi players (女流棋士, joryū kishi) was introduced.

In 1966, Akiko Takojima(蛸島彰子) left the pro qualifier leagues at the 1-dan level and became the first professional woman shogi player. At that there were no women's contests, so her only work as a professional was giving shogi lessons. In 1974, the first women's contest, the Women's Meijin title match (女流名人位戦, joryū meijin-sen) was held, and won by Takojima, who became the first woman meijin. The Ladies’ Shogi Professional (女流棋士会, joryū kishi kai) organisation celebrates "anniversary parties" counting from 1974.

At present there are more than fifty professional women players, and six women’s competitions: the Women's Meijin title match, the Women's Ōshō title match (女流王将戦), the Women's Ōi title match (女流王位戦), the Ōyama Meijin Cup Kurashiki-Tōka title match (大山名人杯倉敷藤花戦), the Ladies' Open Tournament (レディースオープントーナメント) and the Kajima Cup Women's Shogi Tournament (鹿島杯女流将棋トーナメント). In addition, each of the standard professional tournaments has a women's section, in which the top women in each tournament compete.

Trends in the World of Amateur Shogi

Shogi has two different rating systems, based on dan and kyu ranks, one for amateurs and one for professionals, with the highest ranks at amateur level, 4-dan or 5-dan, being equivalent to 6-kyu at the professional level. In the past, there were games between amateurs and professionals, but these were generally special match-ups organized by newspapers or magazines, or instructional games at events or shogi courses. Some amateurs rival professionals in ability, and sometimes earn a living as shinken-shi (真剣師), gamblers playing for stakes. Motoji Hanamura (花村元司) lived on his winnings as a shinken-shi, before taking the entrance exam and turning professional in 1944. Jūmei Koike (小池重明) was another shinken-shi, who beat one professional after another in special matches, and won the title of amateur meijin twice in a row. A vote was held by the general assembly of the Japanese Shogi Association (棋士総会) on whether to accept Koike among their ranks, but there were concerns about his behavior, and the vote went against him. Although he never became a professional, after his death, television program and books told his story, and he now has more fans all over Japan than when he was alive.

In recent times, the gap in ability between strong amateurs and professionals continues to diminish, and there are even official professional tournaments in which those with the best results in amateur shogi contests(将棋のアマチュア棋戦) can participate. A number of players have left the pro qualifier leagues and gone on to have success as amateurs.

In 2006, the Shogi Association officially admitted amateurs and women professionals to the professional (正棋士) ranks, and announced details of an entrance exam for the 4-dan level and the third-level pro qualifier league (奨励会三段リーグ).

International Shogi

Because shogi developed independently inside Japan, and its pieces are differentiated by Japanese characters written on them, it has not spread internationally like the game of Go. In the 1990's, efforts to make shogi popular outside Japan began in earnest. It become particularly popular in the People's Republic of China, and especially Shanghai. The January 2006 edition of Kindai Shogi (近代将棋) states that Shanghai has a shogi population of 120,000 people. The game has been relatively slow to spread to countries where Chinese characters are not in common use, although attempts have been made to aid adoption by replacing the names of pieces with symbols indicating how they move.

Numbers of Shogi Players

According to the "Leisure White Paper" (レジャー白書) by the Japanese Productivity Center for Socio-Economic Development (財団法人社会経済生産性本部), the "shogi population" (the number of people of 15 years or over who play at least one game of shogi a year) fell from 16.8 million in 1985 to 9 million in 2004, and 8.4 million in 2006, and is continuing to fall gradually. Though shogi has often appeared in the media during these decades, the publicity has not led to a "shogi boom." In Japan, shogi is most popular among ten to nineteen-year-olds. Beginning around 1996, internet shogi programs such as Java Shogi (Java将棋) and The Great Shogi (ザ・グレート将棋), which allow users to play games over the internet without the need for an actual shogi set, have become popular.

Computer Shogi

Developments have been made in computer shogi, a field of artificial intelligence concerned with the creation of computer programs which can play shogi. The research and development of shogi software has been carried out mainly by freelance programmers, university research groups and private companies. As the game of shogi has the distinctive feature of allowing captured pieces to be reused, shogi playing programs require a far higher degree of sophistication than programs playing similar games such as chess. During the 1980s, due to the immaturity of technology, computer shogi programs achieved the level of an amateur of kyu rank. It is currently estimated that the strongest program is prefecture champion class (around amateur 5-dan). Computers are best suited to brute-force calculation, and far outperform humans at the task of finding ways of checkmating from a given position, which is simply information processing. In games with time limits of 10 seconds from the first move, computers are becoming a tough challenge for even professional shogi players.

In 2005, the Japan Shogi Association sent a communication to professional shogi players and women professionals, telling them that they should not compete against a computer in public without permission. The intention is to preserve the dignity of shogi professionals, and to make the most of computer shogi as a potential business opportunity.

Rules of the game

Objective

Technically the game is won when a king is captured, though in practice defeat is conceded at checkmate or when checkmate becomes inevitable.

Game Equipment

Two players, Black and White (or sente 先手 and gote 後手), play on a board composed of squares (actually rectangles) in a grid of nine ranks (rows) by nine files (columns). The squares are undifferentiated by marking or colour.

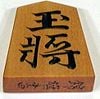

Each player has a set of twenty wedge-shaped pieces of slightly different sizes. Except for the kings, opposing pieces are differentiated only by orientation, not by marking or color. From largest to smallest (most to least powerful), the pieces are:

- 1 King (chess)|king

- 1 rook

- 1 bishop

- 2 gold generals

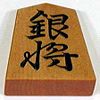

- 2 silver generals

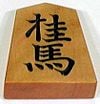

- 2 knights

- 2 lances

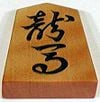

- 9 pawns

Several of these names were chosen to correspond to their rough equivalents in international chess and not as literal translations of the Japanese names.

Each piece has its name written on its surface in the form of two Japanese characters(kanji), usually in black ink. On the reverse side of each piece, other than the king and gold general, are one or two other characters, in amateur sets often in a different color (usually red); this side is turned face up during play to indicate that the piece has been promoted. The pieces of the two players do not differ in color, but instead each faces forward, toward the opposing side. This shows who controls the piece during play.

The Japanese characters deterred many foreigners from learning shogi. This has led to "Westernized" or "international" pieces, which replace the characters with iconic symbols. However, partially because the traditional pieces are already ranked by size, with more powerful pieces being larger, most Western players soon learn to recognize them, and Westernized pieces have never become popular.

Following is a table of the pieces with their Japanese representations and English equivalents. The abbreviations are used for game notation and often to refer to the pieces in speech in Japanese.

* The kanji 竜 is a simplified form of 龍.

English speakers sometimes refer to promoted bishops as horses and promoted rooks as dragons, after their Japanese names, and generally use the Japanese term tokin for promoted pawns. Silver generals and gold generals are commonly referred to simply as silvers and golds.

The characters inscribed on the reverse sides of the pieces to indicate promoted rank may be in red ink, and are usually cursive. The characters on the backs of the pieces that promote to gold generals are cursive variants of 金 'gold', becoming more cursive (more abbreviated) as the value of the original piece decreases. These cursive forms have these equivalents in print: 全 for promoted silver, 今 for promoted knight, 仝 for promoted lance, and 个 for promoted pawn (tokin). Another typographic convention has abbreviated versions of the unpromoted ranks, with a reduced number of strokes: 圭 for a promoted knight (桂), 杏 for a promoted lance (香), and the 全 as above for a promoted silver, but と for tokin.

Player Ranking

Shogi players use the same ranking system as martial arts. Players are ranked from 15 kyū to 1 kyū and then from 1 dan and upwards; the same terminology is used in go. Professional players operate with their own scale, from professional 4 dan and upwards to 9 dan for elite players. Amateur and professional ranks are offset.

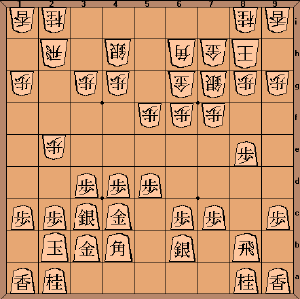

Setup

Each player places his pieces in the positions shown below, facing the opponent.

- In the rank nearest the player:

- The king is placed in the center file.

- The two gold generals are placed in the adjacent files to the king.

- The two silver generals are placed adjacent to each gold general.

- The two knights are placed adjacent to each silver general.

- The two lances are placed in the corners, adjacent to each knight.

That is, the first rank is

L N S G K G S N L

- or

香 桂 銀 金 玉 金 銀 桂 香

- In the second rank, each player places:

- The bishop in the same file as the left knight.

- The rook in the same file as the right knight.

- In the third rank, the nine pawns are placed one to each file.

Traditionally, even the order of placing the pieces on the board is determined. There are two recognized orders, ohashi and ito.

Placement sets pieces with multiples (generals, knights, lances) from left to right in all cases, and follows the order:

- king

- gold generals

- silver generals

- knights

- In ito, the player now places:

- 5. pawns (left to right starting from the leftmost file)

- 6. lances

- 7. bishop

- 8. rook

- In ohashi, the player now places:

- 5. lances

- 6. bishop

- 7. rook

- 8. pawns (starting from center file, then alternating left to right one file at a time)

Gameplay

The players alternate taking turns, with Black playing first. (The terms "Black" and "White" are used to differentiate the two sides, but there is no actual difference in the color of the pieces.) For each turn a player may either move a piece which is already on the board and potentially promote it, capture an opposing piece, or both; or "drop" a piece that has already been captured onto an empty square of the board. These options are detailed below.

Professional games are timed as in International Chess, but professionals are never expected to keep time in their games. Instead a timekeeper is assigned, typically an apprentice professional. Time limits are much longer than in International Chess (9 hours a side plus extra time in the prestigious Meijin title match), and in addition byōyomi ("second counting") is employed. This means that when the ordinary time has run out, the player will from that point on have a certain amount of time to complete every move (a byōyomi period), typically upwards of one minute. The final ten seconds are counted down, and if the time expires the player whose turn it is to move loses the game immediately. Amateurs often play with electronic clocks that beep out the final ten seconds of a byōyomi period, with a prolonged beep for the last five.

Movement and Capture

If an opposing piece occupies a legal destination for a friendly piece (that is, a piece belonging to the player whose turn it is to move), it may be captured by removing it from the board and replacing it with the friendly piece. It is not possible to move to or through a square occupied by another friendly piece, or to move through a square occupied by an opposing piece. It is common to keep captured pieces on a wooden stand (or komadai) which is traditionally placed so that its bottom left corner aligns with the bottom right corner of the board from the perspective of each player. It is not permissible to hide pieces from full view. This is because captured pieces, which are said to be in hand, have a crucial impact on the course of the game.

The knight jumps, that is, it passes over any intervening piece, whether friend or foe, without an effect on either. It is the only piece to do this.

The lance, bishop, and rook are ranging pieces: They can potentially move any number of squares along a straight line limited by the edge of the board. If an opposing piece intervenes, it may be captured by removing it from the board and replacing it with the moving piece. If a friendly piece intervenes, one is limited to a distance that stops short of that square; if the friendly piece is adjacent, one may not move in that direction at all.

All pieces but the knight move either orthogonally (that is, forward, backward, or to the side, in the direction of one of the arms of a plus sign, +), or diagonally (in the direction of one of the arms of a multiplication sign, ×).

King

A King can move one square in any direction, orthogonal or diagonal.

|

Rook

A rook can move any number of free squares along any one of the four orthogonal directions.

|

Bishop

A bishop can move any number of free squares along any one of the four diagonal directions.

|

Because they cannot move orthogonally, the opposing unpromoted bishops can only reach half the squares of the board.

Gold general

A gold general can move one square orthogonally, or one square diagonally forward, giving it six possible destinations. It cannot move diagonally backward.

|

Silver general

A silver general can move one square diagonally or one square directly forward, giving it five possibilities.

|

Because an unpromoted silver can retreat more easily than a promoted one (see below), it is very common to leave a silver unpromoted at the far side of the board.

Knight

A knight jumps at an angle intermediate between orthogonal and diagonal, amounting to one square forward plus one square diagonally forward, in a single motion. That is, it has a choice of two forward destinations. It cannot move to the sides or backwards.

|

The knight is the only piece that ignores intervening pieces on the way to its destination. It is not blocked from moving if the square in front of it is occupied, but neither can it capture a piece on that square.

It is often useful to leave a knight unpromoted (see below) at the far side of the board. However, since a knight cannot move backward or to the sides, it must promote when it lands on one of the two far ranks and would otherwise be unable to move further.

Lance

A lance can move any number of free squares directly forward. It cannot move backward or to the sides.

|

It is often useful to leave a lance unpromoted (see below) at the far side of the board. However, since a lance cannot move backward or to the sides, it must promote if it arrives at the far rank.

Pawn

A pawn can move one square directly forward. It cannot retreat.

|

Since a pawn cannot move backward or to the sides, it must promote (see below) if it arrives at the far rank. However, in practice, a pawn is promoted whenever possible.

Unlike the pawns of international chess, shogi pawns capture the same way they otherwise move, directly forward.

There are two restrictive rules for where a pawn may be dropped. (See below.)

Promotion

A player's promotion zone is the far third of the board, the three ranks occupied by the opposing pieces at setup. If a piece moves across the board and part of that path lies within the promotion zone, that is, if it moves into, out of, or wholly within the zone, but not if it is dropped (see below), then that player may choose to promote the piece at the end of the turn. Promotion is indicated by turning the piece over after it moves, revealing the character for the promoted rank.

| 歩 | 歩 | 歩 | 歩 | 歩 | 歩 | 歩 | 歩 | 歩 |

| 角 | 飛 | |||||||

| 香 | 桂 | 銀 | 金 | 王 | 金 | 銀 | 桂 | 香 |

When captured, pieces lose their promoted status. Otherwise promotion is permanent.

Promoting a piece has the effect of changing how that piece moves. Each piece promotes as follows:

- A silver general, knight, lance, or pawn replaces its normal power of movement with the power of a gold general.

- A rook or bishop keeps its original power of movement and gains the power to move one square in any direction, like a king. This means that a promoted bishop is able to reach any square on the board, given enough moves.

- A king or a gold general cannot promote, nor can pieces which are already promoted.

Promoted Rook

A promoted rook ("dragon") may move as a rook or as a king, but not as both on the same turn.

|

Promoted bishop

A promoted bishop ("horse") may move as a bishop or as a king, but not as both on the same turn.

|

Mandatory promotion

If a pawn or lance reaches the far rank or a knight reaches either of the two farthest ranks, it must promote, as it would otherwise have no legal move on subsequent turns. A silver never needs to promote, and it is often advantageous to keep a silver unpromoted.

Drops

| Piece | Init. | Max | Min |

|---|---|---|---|

| King | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Rook(s) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Bishop(s) | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Gold generals | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Silver generals | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Knights | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Lances | 2 | 4 | 0 |

| Pawns | 9 | 9 | 0 |

| Tokins | 0 | 18 | 0 |

Captured pieces are truly captured in shogi. They are retained "in hand", and can be brought back into play under the capturing player's control. On any turn, instead of moving a piece on the board, a player may take a piece that had been previously captured and place it, unpromoted side up, on any empty square, facing the opposing side. The piece is now part of the forces controlled by that player. This is termed dropping the piece, or just a drop.

A drop cannot capture a piece, nor does dropping within the promotion zone result in immediate promotion. However, either capture or promotion may occur normally on subsequent moves by the piece.

A pawn, knight, or lance may not be dropped on the far rank, since it would have no legal move on subsequent turns. Similarly, a knight may not be dropped on the penultimate rank.

There are two other restrictions when dropping pawns:

- A pawn cannot be dropped onto the same file (column) as another unpromoted pawn controlled by the same player. (A tokin does not count as a pawn.) A player who has an unpromoted pawn on every file is therefore unable to drop a pawn anywhere. For this reason it is common to sacrifice a pawn in order to gain flexibility for drops.

- A pawn cannot be dropped to give an immediate checkmate. However, other pieces may be dropped to give immediate checkmate, a pawn that is already on the board may be advanced to give checkmate, and a pawn may be dropped so that either it or another piece can give checkmate on a subsequent turn.

It is common for players to swap bishops, which face each other across the board. This leaves each player with a bishop "in hand" to be dropped later, and gives an advantage to the player with the stronger defensive position.

Check and Mate

When a player makes a move such that the opposing king could be captured on the following turn, the move is said to give check to the king; the king is said to be in check. If a player's king is in check and no legal move by that player will get the king out of check, the checking move is also checkmate (tsume 詰め or ōtedzume 王手詰め) and effectively wins the game.

To give the warning "check!" in Japanese, one says "ōte!" (王手). However, this is an influence of international chess and is not required, even as a courtesy.

A player is not allowed to give perpetual check.

Winning the Game

A player who captures the opponent's king wins the game. In practice this rarely happens, as a player will concede defeat when loss is inevitable.

In professional and serious amateur games, a player who makes an illegal move loses immediately.

There are two other possible, if uncommon, ways for a game to end: repetition (千日手 sennichite) and impasse (持将棋 jishōgi).

If the same game position occurs four (formerly three) times with the same player to play, the game is declared no contest. For two positions to be considered the same, the pieces in hand must be the same as well as the positions on the board. However, if this occurs with one player giving perpetual check, then that player loses.

The game reaches an impasse if both kings have advanced into their respective promotion zones and neither player can hope to mate the other or to gain any further material. If this happens, the winner is decided as follows: Each rook or bishop scores 5 points for the owning player, and all other pieces except kings score 1 point each. (Promotions are ignored for the purposes of scoring.) A player scoring less than 24 points loses. Jishōgi is considered an outcome in its own right rather than no contest, but there is no practical difference.

In professional tournaments the rules typically require drawn games to be replayed with colors (sides) reversed, possibly with reduced time limits. This is rare compared to chess and xiangqi, occurring at a rate of 1-2% even in amateur games. The 1982 Meijin title match between Nakahara Makoto and Kato Hifumi was unusual in this regard, with jishōgi in the first game (only the fifth draw in the then 40-year history of the tournament), a game which lasted for an unusual 223 moves (not counting in pairs of moves), with an astounding 114 minutes spent pondering a single move, and sennichite in the sixth and eighth games. Thus this best-of-seven match lasted ten games and took over three months to finish; Black did not lose a single game and the eventual victor was Katō at 4-3.

Handicaps

Games between players of disparate strengths are often played with handicaps. In a handicap game, one or more of White's pieces are removed from the setup, and in exchange White plays first. Note that the missing pieces are not available for drops and play no further part in the game. The imbalance created by this method of handicapping is not as strong as it is in international chess because material advantage is not as powerful in shogi.

Common handicaps, in increasing order of severity, include,

- Left lance

- Bishop

- Rook

- Rook and left lance

- Rook and bishop

- Four pieces: Rook, bishop, and both lances

- Six pieces: Rook, bishop, both lances and both knights

Other handicaps are also occasionally used. The relationship between handicaps and differences in rank is not universally agreed upon, with several systems in use.

Game Notation

The method used in English-language texts to express shogi moves was established by George Hodges in 1976. It is derived from the algebraic notation used for chess, but differs in several respects. It is not used in Japanese-language texts, as it is no more concise than kanji.

A typical move might be notated P-8f. The first letter represents the piece moved: P for Pawn. (There is also L lance, N knight, S silver, G gold, B bishop, R rook, K king, as above.) Promoted pieces are indicated by a + in front of the letter: +P is a tokin (promoted pawn).

Following the abbreviation for the piece is a symbol for the type of move: – for a simple move, x for a capture, or * for a drop. Next is the square on which the piece lands. This is indicated by a numeral for the file and a lowercase letter for the rank, with 1a being the top right corner (as seen by Black) and 9i being the bottom left corner. This is based on Japanese convention, which, however, uses Japanese numerals instead of letters. For example, square 2c is "2三" in Japanese.

If a move entitles the player to promote, then a + is added to the end if the promotion was taken, or an = if it was declined. For example, Nx7c= indicates a knight capturing on 7c without promoting.

In cases where the piece is ambiguous, the starting square is added to the letter for the piece. For example, at setup Black has two golds which can move to square 5h (in front of the king). These are distinguished as G6i-5h (from the left) and G4i-5h (from the right).

Moves are commonly numbered as in chess. For example, the start of a game might look like this:

1. P-7f P-3d

2. P-2f G-3b

3. P-2e Bx8h+

4. Sx8h S-2b

In handicap games White plays first, so Black's move 1 is replaced by an ellipsis.

Strategy and Tactics

Drops are the most serious departure from International Chess. They entail a different strategy, with a strong defensive position being much more important. A quick offense will leave a player's home territory open to drop attacks as soon as pieces are exchanged. Because pawns attack head on, and cannot defend each other, they tend to be lost early in the game, providing ammunition for such attacks. Dropping a pawn behind enemy lines, promoting it to a "tokin", and dropping a second pawn immediately behind the "tokin" so that they protect each other makes a strong attack; it threatens the opponent's entire defense, but provides little of value if the attack fails and the pieces are captured.

Players raised on International Chess often make poor use of drops, but in Shogi, dropping is half the game. If a player has more than two captured pieces in hand, it is an indication that he is overlooking dropping attacks. However, it is wise to keep a pawn in hand, and often to exchange pieces if necessary to get one.

A decision that will be made early in the game is whether to exchange bishops. If exchanged, it may be possible to drop a bishop behind poorly defended enemy territory for a fork attack, threatening two vital pieces at once. (Silvers are also commonly used this way.) Even if a dropped bishop immediately retreats, it may promote in doing so, and a promoted bishop can dominate the board — it is a particularly strong defensive piece.

Attacking pieces can easily become trapped behind enemy lines, as the opponent can often drop a pawn on a protected square to cut off the line of retreat. For this reason, rooks, which can retreat in only one direction, are commonly kept at a safe distance in the early parts of the game, and used to support attacks by weaker pieces. However, once the game has opened up, a promoted rook is an especially deadly piece behind enemy lines.

Many common opening attacks involve advancing a silver along a file protected by the rook. Because silvers have more possibilities for retreat, while golds better defend their sides, silvers are generally considered superior as attacking pieces, and golds superior as defensive pieces. It is common practice to defend the king with three generals, two golds and a silver.

There are various furibisha or "ranging rook" openings where the rook moves to the center or left of the board to support an attack there, typically with the idea of allowing the opponent to attack while arranging a better defense and aiming for a counterattack. However, as the most powerful piece on the board, the rook invites attack, and in most cases, especially for weaker players, it is a good idea to keep the king well away from the rook. Leaving a king on its original square (igyoku or a "sitting king") is a particularly dangerous position.

Advancing a lance pawn can open up the side of the board for attack. Therefore, when a player first advances a lance pawn, it is usual for the opponent to answer by advancing the opposing pawn, in order to avoid complications later in the game.

Because defense is so important, and because shogi pieces are relatively slow movers, the opening game tends to be much longer in shogi than in International Chess, commonly with a dozen or more moves to shore up defenses before the initial attack is made. There are several strong defensive fortifications known as castles.

The Yagura Castle

The Yagura castle is considered by many to be the strongest defensive position in shogi. It has a strongly protected king; a well fortified line of pawns; and the bishop, rook, and a pawn all support a later attack by the rook's silver or knight. It is notoriously difficult to break down with a frontal assault, though it is weaker from the side. It is typically used against ibisha or "static rook" openings, which involve advancing the rook's pawn. However, one's opponent may just as easily adopt this defense, giving neither side an advantage.

Instead of the rook's pawn being advanced two squares as shown in the diagram, the adjacent silver's pawn is often advanced one square, allowing both the rook's silver and knight to move forward. These offensive moves are not properly part of the castle, but the two-square pawn advance must be carried out early if there is to be room for it, and so it is often done while still castling.

There is a good deal of flexibility in the order of moves when building the Yagura defense, and the possibilities will not be listed here. The only point to keep in mind is that the generals should move diagonally, not directly forward. However, there is a strong intermediate position called the kani ("crab"). It has the three pawns on the left side advanced to their final Yagura positions, and on the second rank all four generals are lined up next to the bishop, which is still in its starting position: {{overline||B|G|S|G|S| bishop-gold-silver-gold-silver. The king is moved one square to the left, behind the middle silver.

A common attack against the Yagura defense is to advance the rook's knight directly forward, with a pawn in hand, to attack the fortifications on either side of the castled king. If the defender has answered a lance's pawn advance on that side, a pawn may be dropped where the edge pawn had been. If the defending silver has moved or is not yet in position, a pawn may be dropped there.

Professional players

- In Japan, about 200 professional shogi players who are members of Japan Shogi Association have games with each other for seven titles: Meijin (名人), Kisei (棋聖), Ōshō (王将), Ōza (王座), Ōi (王位), RyūŌ (竜王) and Kiō (棋王). The winner of previous year will have to defend the title from the challenger chosen from knockout or round matches. The latest, most famous champion, Yoshiharu Habu, is said to earn more than US$1,000,000 each year. He is also one of the best chess players in Japan and is ranked with FM level.

- Current title holders:

- 2006 64th Meijin: Moriuchi Toshiyuki (won over Tanigawa Koji 4-2)

- 2005 18th RyūŌ: Watanabe Akira (won over Kimura Kazuki 4-0)

- 2006 77th Kisei: Satō Yasumitsu (won over Suzuki Daisuke 3-0)

- 2006 47th Ōi: Habu Yoshiharu (won over Satō Yasumitsu 4-2)

- 2006 54th Ōza: Habu Yoshiharu (won over Satō Yasumitsu 3-0)

- 2006 55th Ōshō: Habu Yoshiharu (won over Satō Yasumitsu 4-3)

- 2006 31st Kiō: Moriuchi Toshiyuki (won over Habu Yoshiharu 3-1)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Fairbairn, J. Shogi for Beginners . Ishi Pr; 2nd ed edition, 1984. ISBN 4871872017

- Hosking, T. The Art of Shogi. Shogi Foundation, 1997. ISBN 0953108902

- Teruichi, A.; Fairbairn, J. (translator) Better Moves for Better Shogi. Masao Kawai, 1983.

- Habu, Y.; Takahashi, Y. (translator); Hoksing, T. (translator) Habu's Words. Shogi Foundation, 2000. ISBN 0953108929

- SHOGI Magazine (70 issues, January 1976 - November 1987) by The Shogi Association (edited by George Hodges)

External links

All links retrieved January 27, 2023.

Online games

- shogi online free - Shogi for playing online in real-time

Regional organizations

- Shogi.de - Japanese Chess in Germany

- Shogi.fr - Japanese Chess in France

- A.S.A. - Association Shogi d'Alsace

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- Much of the History section was translated from the section in the Japanese Wikipedia, as retrieved on September 17, 2006.