Shatt al-Arab

| Shatt al-Arab | |

|---|---|

| Shatt al-Arab near Basra, Iraq . | |

| Origin | TigrisâEuphrates confluence at Al-Qurnah |

| Mouth | Persian Gulf |

| Basin countries | Iran, Iraq |

| Length | 200Â km (120Â mi) |

| Source elevation | 4Â m (13Â ft) |

| Mouth elevation | 0Â m (0Â ft) |

| Avg. discharge | 1,750 m³/s (62,000 cu ft/s) |

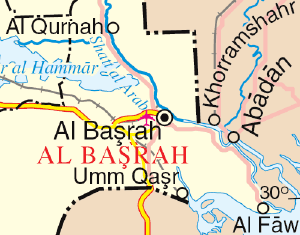

The Shatt al-Arab, known in Iran as the Arvand Rud, is a river in Southwest Asia stretching more than 200Â kilometers (124Â mi) in length. It is formed by the confluence of the Euphrates and the Tigris in the town of al-Qurnah in southern Iraq. The southern end of the river constitutes the border between Iraq and Iran to the mouth of the river where it discharges into the Persian Gulf. The river varies in width from about 232Â meters (760Â ft) at Basra to 800Â meters (2,600Â ft) at its mouth. It is thought that the waterway formed relatively recently in geologic time, with the Tigris River and Euphrates River originally emptying into the Persian Gulf via a channel farther to the west.

In Middle Persian literature and the Shahnama, the name Arvand is used for the Tigris, the confluent of the Shatt al-Arab. Iranians began using this name specifically to designate the Shatt al-Arab during the later Pahlavi period, and continued to do so after the Iranian Revolution of 1978â1979.

The area is judged to hold the largest date palm forest in the world. In the mid-1970s, the region included 17 to 18 million date palms, an estimated one-fifth of the world's 90 million palm trees. But by 2002, war, salt, and insects had wiped out more than 14 million of the palms, including around 9 million in Iraq and 5 million in Iran. Many of the remaining 3 to 4 million trees are in poor condition, though the forests are slowly being revived.

Geography

The general climate of the Shatt al-Arab region is subtropical, hot, and arid. At the northern end of the Persian Gulf is a vast floodplain formed by the Euphrates, Tigris, and Karun Rivers, featuring huge permanent lakes, marshes, and forest. The aquatic vegetation includes reeds, rushes, and papyrus, which support numerous species. The marshy land is home to water birds, some stopping here while migrating, and some spending the winter by feeding on lizards, snakes, frogs, and fish. Other animals found in these marshes are domestic water buffalo, two endemic rodent species, antelopes, gazelles, small animals such as the jerboa, and several other mammals.

Salinization of the soil that supported the date palm forest began emerging as a problem in the late 1960s. The situation rapidly deteriorated as dam construction intensified throughout the Tigris-Euphrates basin, considerably reducing freshwater flows and eliminating periodic flooding of the Shatt al-Arab that formerly washed out accumulated salts. In addition, with the outbreak of the Iran-Iraq War in 1980 the palm forest was caught in the prolonged and intense crossfire.

The date palms, whose botanical name is Phoenix dactylifera L., are named for the mythical Phoenix bird that sprang from the ashes; date palms are also able to regenerate from fire damage. The palm tree's fruit is one of the oldest cultivated tree crops, with a history of over 5,000 years. The nutritious and flavorful date is a traditional staple food of the Middle East and also the source of syrup, alcohol, and vinegar. Other date palm componentsâseeds, wood, and leavesâhave a wide diversity of applications, including: ground-up seedsâanimal feed and a coffee additive; oilâsoap and cosmetics; woodâposts and rafters; leaves, including the petiolesâmats, screens, fans, rope, and fuel.

Biotechnology may help replace the millions of palms that have been destroyed. Iran is using a new cloning technique to accelerate mass date production, as dates are naturally slow to propagate. Since 2002, thousands of palm plantlets have been introduced.[1] Date palms can take four to seven years after planting before they will bear fruit, and produce viable yields for commercial harvest when they reach between seven and ten years. Mature date palms can produce 176â264 pounds (80â120 kilograms) of dates per harvest season, although they do not all ripen at the same time so several harvests are required.

History

Conflicting territorial claims and disputes over navigation rights between Iran and Iraq were among the main factors for the Iraq-Iran War that lasted from 1980 to 1988, when the pre-1980 status quo was restored. The Iranian cities of Abadan and Khorramshahr and the Iraqi city and major port of Basra are situated along this river.

Territorial disputes

Control of the waterway and its use as a border have been a source of contention between the predecessors of the Iranian and Iraqi states since a peace treaty was signed in 1639 between the Persian and the Ottoman Empires. The treaty divided the territory according to tribal customs and loyalties, without attempting a rigorous land survey. The tribes on both sides of the lower waterway, however, are Marsh Arabs, and the Ottoman Empire claimed to represent them.

Tensions between the opposing empires that extended across a wide range of religious, cultural, and political conflicts, led to the outbreak of hostilities in the nineteenth century and eventually yielded the Second Treaty of Erzurum between the two parties in 1847, after protracted negotiations, which included British and Russian delegates. Even afterward, backtracking and disagreements continued, until the British Foreign Secretary, Lord Palmerston, was moved to comment in 1851 that "the boundary line between Turkey and Persia can never be finally settled except by an arbitrary decision on the part of Great Britain and Russia." A protocol between the Ottomans and the Persians was signed in Istanbul in 1913, but World War I canceled all plans.

The British advisers in Iraq were able to keep the waterway binational under the thalweg principle that has worked in Europe: the dividing line was a line drawn between the deepest points along the stream bed. All United Nations attempts to intervene as mediators were rebuffed. Under Saddam Hussein, Baathist Iraq claimed the entire waterway up to the Iranian shore as its territory. But in 1975, Iraq signed the Algiers Accord in which it recognized a series of straight lines closely approximating the thalweg of the waterway as the official border. In 1980, Hussein released a statement claiming to abrogate the treaty that he had signed, and Iraq invaded Iran. (International law holds that no bilateral or multilateral treaty can be abrogated by only one party.)

The main thrust of the military movements on the ground was across the waterway, which was the stage for most of the military battles between the two armies. The waterway was Iraq's only outlet to the Persian Gulf, and thus, its shipping lanes were greatly affected by continuous Iranian attacks. When the Al-Faw peninsula was captured by the Iranians in 1987, Iraq's shipping activities virtually came to a halt and had to be diverted to other Arab ports, such as Kuwait and even Aqaba, Jordan. At the end of the IranâIraq War both sides agreed to once again treat the Algiers Accord as binding.

Recent conflicts

In the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the waterway was a key military target for the Coalition Forces. Since it is the only outlet to the Persian Gulf, its capture was important in delivering humanitarian aid to the rest of the country, and also to stop the flow of illegal smuggling operations. British Royal Marines staged an amphibious assault to capture the key oil installations and shipping docks located at Umm Qasr on the al-Faw peninsula at the onset of the conflict.

Following the end of the war, the United Kingdom was given responsibility, subsequently mandated by United Nations Security Council Resolution 1723, to patrol the waterway and the area of the Persian Gulf surrounding the river mouth. They were tasked to make sure that ships in the area were not being used to transport munitions into Iraq. British forces also trained Iraqi naval units to take over the responsibility of guarding their waterways.

On two separate occasions, Iranian forces operating on the Shatt al-Arab captured British Royal Navy sailors who they claimed had trespassed into their territory.

- In June 2004, several British servicemen were held for two days after purportedly straying into the Iranian side of the waterway. After being initially threatened with prosecution, they were released after high-level conversations between the British Foreign Secretary, Jack Straw, and the Iranian Minister of Foreign Affairs, Kamal Kharrazi. The initial hard-line approach was put down to power struggles within the Iranian government. The British marines' weapons and boats were confiscated.

- In 2007, a seizure of 15 more British personnel became a major diplomatic crisis between the two nations. It was resolved after 13 days when the Iranians unexpectedly released the captives under an "amnesty."

Looking to the future

The Shatt al-Arab suffers from the religion and politics of the neighboring nations, Iran and Iraq, whose border falls in the river at its southern end. But control of the waterway and its use as a border have been a source of contention between the predecessors of the Iranian and Iraqi states since a peace treaty was signed in 1639 between the Persian and the Ottoman Empires. UnderSaddam Hussein, Iraq claimed the entire waterway up to the Iranian shore as its territory and invaded Iran in 1980 to back this up.

The waterway became the stage for most of the military battles between the two armies. Though in the end both parties agreed to the resumption of their original border, in the process a good part of the date palm forest on either side of the Shatt al-Arab had been destroyed and is slowly being revived.

The health of the Shatt al-Arab and its ecosystem will remain dependent upon the relationship between the nations through which it flows.

Notes

- â United Nations Environment Programme, Shatt al-Arab Retrieved September 12, 2015.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Elliott, M. "Modern Britain and shame in the Shatt al Arab waterway." TIME -New York- American Edition. 169 (17) (2007): 52-52. OCLC 207883715

- Kasheff, M. ARVAND-RĹŞD Iranica. Retrieved September 12, 2015.

- Penn, James R. Rivers of the world: a social, geographical, and environmental sourcebook. Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2001. ISBN 9781576070420

- Schofield, Richard N. Evolution of the Shatt al-ĘźArab boundary dispute. Wisbech, Cambridgeshire, England: Middle East & North African Studies Press, 1986. ISBN 9780906559253

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.