Raja Raja Chola I

Extent of the Chola Empire under Rajaraja the Great c.1014 C.E. | |

| Reign | 985 C.E. - 1014 C.E. |

| Title | Rajakesari |

| Capital | Thanjavur |

| Queen | Lokamahadevi Cholamahadevi Trailokyamahadevi Panchavanmahadevi Abhimanavalli Iladamadeviyar Prithivimahadevi |

| Children | Rajendra Chola I Kundavai Madevadigal |

| Predecessor | Uttama Chola |

| Successor | Rajendra Chola I |

| Father | Sundara Chola |

| Born | Unknown |

| Died | 1014 C.E. |

Rajaraja Chola I (Tamil: இராஜராஜ சோழன்), considered as the greatest king of the Chola Empire by many, ruled between 985 and 1014 C.E. He laid the foundation for the growth of the Chola kingdom into an empire, by conquering the kingdoms of southern India and the Chola Empire expanded as far as Sri Lanka in the south, and Kalinga (Orissa) in the northeast. He fought many battles with the Chalukyas in the north and the Pandyas in the south. By conquering Vengi, Rajaraja laid the foundations for the Chalukya Chola dynasty. He invaded Sri Lanka and started a century-long Chola occupation of the island.

He streamlined the administrative system with the division of the country into various districts and by standardizing revenue collection through systematic land surveys. He built the magnificent Brihadisvara Temple in Thanjavur and through it enabled wealth distribution among his subjects. His successes enabled the splendid achievements of his son Rajendra Chola I under whom the empire attained the greatest extent and carried its conquest beyond the seas.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Popular Prince

Rajaraja, the third child of Parantaka Sundara Chola and Vanavan Mahadevi, has also been known by his birth name Arulmozhivarman. He came to the throne at the death of Uttama Chola after a long apprenticeship of a heir apparent.[1] During the lifetime of his father Sundara Chola, Arulmozhi had carved a name for himself by his exploits in the battles against the Sinhala and Pandyan armies. Sundara Chola’s eldest son and heir apparent Aditya II had been assassinated under unclear circumstances.[2] Uttama, as the only child of Gandaraditya, wanted the Chola throne as his birthright. After the death of Aditya II, Uttama forced Sundara Chola to declare himself heir apparent ahead of the popular Arulmozhi.[3] Thiruvalangadu copper-plate inscriptions say:[4]

- "…Though his subjects … entreated Arulmozhivarman, he … did not desire the kingdom for himself even inwardly as long as his paternal uncle coveted [it] …".

Uttama made a compromise deal with Sundara Chola that Uttama will be succeeded not by his son but by Arulmozhi. Thiruvalangadu inscription again states:

- "Having noticed by the marks (on his body) that Arulmozhi was the very Vishnu, the protector of the three worlds, descended on earth, [Uttama] installed him in the position of yuvaraja (heir apparent) and himself bore the burden of ruling the earth … "

Military Conquests

Southern wars

The southern kingdoms of Pandyas, Cheras and the Sinhalas often allied against the Cholas. 'Rajaraja began his conquests by attacking the confederation between the rulers of the Pandya and Krala kingdoms and of Ceylon' [5] When Rajaraja came to the throne, he initially campaigned against the combined Pandya and Chera armies. No evidence exists of any military campaign undertaken by Rajaraja until the eighth year of his reign. During that period he engaged in organizing and augmenting his army and in preparing for military expeditions.[6][7]

Kandalur Salai

The campaign in the Kerala country c 994 C.E. marked the first military achievement of Rajaraja’s reign. Rajaraja’s early inscriptions use the descriptive ‘Kandalur salai kalamarutta’ (காந்தளுர் சாலைக் களமறுத்த). In that campaign Rajaraja reportedly destroyed a fleet in the port of Kandalur, situated in the dominions of the Chera King Bhaskara Ravi Varman Thiruvadi (c. 978 – 1036 C.E.).[8][9] Inscriptions found in Thanjavur show that frequent references to the conquest of the Chera king and the Pandyas in Malai-nadu (the west coast of South India) had been made. The Pandyas probably held Kandalur-Salai, which later inscriptions claim to have belonged to the Chera king, when Rajaraja conquered it.[10] The required a number of years before the conquest attained victory and the conquered country's administration could be properly organized.[11]

In the war against the Pandyas, Rajaraja seized the Pandya king Amarabhujanga and the Chola general captured the port of Virinam. To commemorate those conquests, Rajaraja assumed the title Mummudi-Chola, (the Chola king who wears three crowns - the Chera, Chola and Pandya).[12]

Malai Nadu

In a battle against the Cheras sometime before 1008 C.E., Rajaraja stormed and captured Udagai in the western hill country. Kalingattuparani, a war poem written during the reign of Kulothunga Chola I, hints at a slight on the Chola ambassador to the Chera court as the reason for that sacking of Udagai. Rajaraja’s son Rajendra served as the Chola general leading the army in that battle.[13][14] The Tamil poem Vikkirama Cholan ula mentions the conquest of Malai Nadu and the killing of eighteen princes in retaliation of the insult offered to an envoy.[15] [16]

Invasion of Lanka

To eliminate the remaining actor in the triumvirate, Rajaraja invaded Sri Lanka in 993 C.E. The copper-plate inscription mention that Rajaraja’s powerful army crossed the ocean by ships and burnt up the kingdom of Lanka. Mahinda V had been the king of Sinhalas. In 991 C.E. Mahinda’s army mutinied with help from mercenaries from Keralas. Mahinda had to seek refuge in the southern region of Rohana. Rajaraja utilized that opportunity and invaded the island. Chola armies occupied the northern half of Lanka and named the dominion ‘Mummudi Chola Mandalam’. Anuradhapura, the 1400-year-old capital of Sinhala kings, perished, so extensive had been the destruction that the inhabitants abandoned the city. Cholas made the city of Polonnaruwa as their capital and renamed it Jananathamangalam. The choice of that city demonstrates the desire of Rajaraja to conquer the entire island. Rajaraja also built a Temple for Siva in Pollonaruwa.[17]

Northern wars

Rajaraja also expanded his conquests in the north and northwest. The regions of Gangapadi (Gangawadi), Nolambapadi (Nolambawadi), Tadigaipadi came into Chola possession during Rajaraja.

Ganga wars

Before his 14th year c. 998 – 999 C.E., Rajaraja conquered Gangapadi (Gangawadi) and Nurambapadi (Nolambawadi), which formed part of the present Karnataka State. The Cholas never lost their hold of the Ganga country from the efforts of Sundara Chola, facilitating that conquest. Nolambas, the feudatories of Ganga, could have turned against their overlords and aided the Cholas to conquer the Gangas, the chief bulwark against the Chola armies in the northwest.

The invasion of the Ganga country proved a complete success and the entire Ganga country came under the Chola rule for the next century. The disappearance of Rashtrakutas c. 973 C.E., conquered by the western Chalukyas, aided the easy success against the Gangas. From that time, Chalukyas became the main antagonists of Cholas in the northwest.

Western Chalukya wars

C. 996 C.E. Satyasraya became the Chalukya king.

The circumstances that led to the war with the Chalukya king Satyasraya remain unclear. The conquest of Gangapadi and Nulambapadi must have brought the Cholas into direct contact with the Western Chalukyas. Both the Cholas and the Western Chalukyas had powerful and strong dynasties, they probably had been looking for an opportunity to measure their respective strength. Under those circumstances any slight could provoke a quarrel. The Chalukyas, pressed from the north by the hostile Paramaras of Malwa, must have found sustaining themselves against two powerful enemies attacking from two opposite directions difficult.

An inscription of Rajaraja from c. 1003 C.E. asserts that he captured Rattapadi by force. Rajendra led the Chola armies against the Western Chalukyas. According to the Hottur inscriptions of Satyasraya, dated 1007 – 1008 C.E., the Chola king with a force numbering nine hundred thousand had ‘pillaged the whole country, had slaughtered the women, the children and the Brahmans, and, taking the girls to wife, had destroyed their caste’. Rajaraja’s inscriptions indicate that the Chola army elephants wrought havoc on the banks of the river Tungabhadra. Rajaraja failed to capture the Western Chalukya capital Manyakheta. Though overwhelmed by the strength and rapidity of the Chola advance, Satyasraya soon recovered and, by hard fighting, rolled back the invasion.

Rajaraja evidently attached much importance to his victory over Satyasraya, as he reportedly presented gold flowers to the Rajarajesvara temple on his return from the expedition. At the end of that war, the southern banks of the Thungabadhra river became the frontier between those two empires.

War against Vengi

The Eastern Chalukya dynasty came into existence when Chalukya Pulakesi II conquered Vengi and installed his brother Kubja Vishnuvardhana as the king c 624 C.E. During the next three centuries of rule, marked by many wars with the Rashtrakutas, the dynasty had become old and dysfunctional, falling prey to disputed successions and anarchy. Although the Western Chalukyan Satyasraya tried to amalgamate the two dynasties, he failed due to the constant battles with the Paramaras and the Cholas.

Rajaraja, who aimed at capturing every province that had ever been held by Parantaka I and extend the empire still further, sent a northern expedition early in his reign. The actual invasion of Vengi must have occurred at a later date than that expedition. Perhaps the interference of Satyasraya in the Vengi kingdom provided the trigger.

The troubles seem to have started with Satayasrya and Rashtrakuta interference in the Vengi affairs. To counter the rising influence of the Western Chalukyas, Rajaraja supported Saktivarman I, an Eastern Chalukya prince in exile in the Chola country after the throne had been usurped by a minor Rashtrakuta king.

Rajaraja invaded Vengi in 999 C.E. to restore Saktivarman to the Eastern Chalukya throne. After many hard battles Saktivarman finally found his position secure on the throne in 1002 C.E. Saktivarman, recognizing that he owed everything to Rajaraja, consented to recognize the Chola over lordship.

Origins of the Chalukya Chola dynasty

Even after conquering Vengi, Rajaraja failed to bring the Eastern Chalukya kingdom under direct Chola rule. The Vengi kingdom remained independent of the Chola Empire. Unlike the Pandyan and Chera territories, Eastern Chalukyas maintained an independent political existence and remained as a Chola protectorate. A dynastic marriage between the Vengi prince Vimaladitya and Rajaraja’s daughter Kundavai sealed the alliance between the two ruling families.

Kalinga conquest

The invasion of the kingdom of Kalinga must have occurred subsequent to the conquest of Vengi.[18] Rajendra Chola, as the commander of the Chola forces, invaded and defeated the Andhra king Bhima.

The naval conquest of the ‘old islands of the sea numbering 12,000’, the Maldives marked one of the last conquests of Rajaraja.[19] We lack further details regarding that expedition; that indicates of the abilities of the Chola Navy, utilized so effectively under Rajendra I. Chola Navy also had played a major role in the invasion of Lanka.[20]

The increasing realization of the importance of a good Navy and the desire to neutralize the emerging Chera Naval power probably had been the underlying the reasons for the Kandalur campaign in the early days of Rajaraja’s reign.[21]

Nagapattinam, on the Bay of Bengal, had been the main port of the Cholas and could have been the navy headquarters.

Thanjavur Temple

The magnificent Siva temple in Thanjavur, the finest monument of this period of South Indian history, commemorated Rajaraja’s great reign. The temple, remarkable both for its massive proportions and for its simplicity of design, has been designated a World Heritage Site, forming part of the Great Living Chola Temples site.

The construction of the temple reportedly completed on the 275th day of the 25th year of his reign.[22] After its commemoration, the great temple and the capital had close business relations with the rest of the country and acted as a center of both religious and economic activity. Year after year villages from all over the country had to supply men and material for the temple maintenance.[23]

Administration

From the 23rd to the 29th year of Rajaraja’s rule his dominions enjoyed peace and the king devoted his energies to the task of internal administration. The building of the Rajarajesvara temple in Thanjavur and the various endowments and gifts to it occupied a prominent place in the king’s priorities during those years.

Rajaraja carried out a revenue and settlement during the final years of his reign. Inscriptions found in the Thanjavur temple bear testimony to the accuracy of that operation. He had land as small in extent as 1/52,428,800,000 of a ‘veli’ (a land measure) measured and assessed to revenue. The revenue survey enabled for the confiscation of lands of the defaulting landlords.[24]

Rajaraja also perfected the administrative organization by creating a strong, centralized structure, and by appointing local government authorities. He installed a system of audit and control holding to account the village assemblies and other public bodies while protecting their autonomy.

Military Organization

Rajaraja created a powerful standing army and a considerable navy which achieved even greater success under Rajendra than under himself. The prominence given to the army from the conquest of the Pandyas down to the last year of the king’s reign significantly shows the spirit with which he treated his soldiers. Evidently Rajaraja gave his army its due share in the glory derived from his extensive conquests. A number of regiments have been mentioned in the Tanjore inscriptions.

- Perundanattu Anaiyatkal.

- Pandita-Chola-Terinda-villigal.

- Uttama- Chola-terinda-Andalagattalar.

- Nigarili- Chola terinda-Udanilai-Kudiraichchevagar.

- Mummadi- Chola-terinda-Anaippagar.

- Vira- Chola-Anukkar.

- Parantaka-Kongavalar.

- Mummadi- Chola-terinda-parivarattar.

- Keralantaka-terinda-parivarattar.

- Mulaparivara-vitteru alias Jananatha-terinda-parivarattar.

- Singalantaka-terinda-parivarattar.

- Sirudanattu Vadugakkalavar.

- Valangai-Parambadaigalilar.

- Perundanattu-Valangai-Velaikkarappadaigal.

- Sirudanattu-Valangai-Velaikkarappadaigal.

- Aragiya- Chola-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Aridurgalanghana-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Chandaparakrama-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Ilaiya-Rajaraja-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Kshatriyasikhamani-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Murtavikramabharana-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Nittavinoda-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Rajakanthirava-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Rajaraja-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar

- Rajavinoda-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Ranamukha-Bhima-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Vikramabharana-terinda-Valangai-Velaikkarar.

- Keralantaka-vasal-tirumeykappar.

- Anukka-vasal-tirumeykappar.

- Parivarameykappargal.

- Palavagai-Parampadaigalilar.

In most of the foregoing names the first portion represents the surnames or titles of the king himself or of his son. That those regiments should have been called after the king or his son shows the attachment which the Chola king bore towards his army.

Those royal names, most likely, had been pre-fixed to the designations of those regiments after they had distinguished themselves in some engagement or other. Elephant troops, cavalry and foot soldiers comprise these regiments. The management of certain minor shrines of the temple had been entrusted to some of those regiments, with the expectation that they provide for the requirements of the shrine. Others among them took money from the temple on interest, which they agreed to pay in cash. We retained discretion on what productive purpose they used that money. At any rate, all those transactions show that the king created in them an interest in the temple he built.

Officials and Feudatories

Rajendra Chola became co-regent, as well as the Mahadandanayaka Panchavan Maharaya – supreme commander- of the northern and northwestern dominions during the last years of Rajaraja’s rule. Paluvettaraiyars, from the region of Thiruchirapalli, closely associated with the Cholas from the time of Parantaka I when he married a Paluvettaraiyar princess, occupying a high position in the Chola administration. They apparently enjoyed full responsibility and administration of the region of Paluvur. Adigal Paluvettaraiyar Kandan Maravan had been one of the names of those feudal chieftains found in inscriptions.

Gandaraditya’s son Madurantakan Gandaradityan served in Rajaraja’s court as an important official in the department of temple affairs. He conducted inquiries into temple affairs in various parts of the country, punishing defaulters. The other names of officials found in the inscriptions include the Bana prince Maravan Narasimhavarman, a general Senapathi Sri Krishnan Raman, the revenue official Irayiravan Pallavarayan and Kuruvan Ulagalandan who organized the country-wide land surveys.

Standardized Inscriptions

Rajaraja recorded his military achievements in every one of his inscriptions and thus handed down to posterity some of the important events of his life. Rajaraja had the first king of South India to introduce that innovation into his inscriptions. Before his time powerful kings of the Pallava, Pandya and Chola dynasties had reigned in the South, and some of them had made extensive conquests. But none of them seems to have thought of leaving a record on stone of his military achievements.

The idea of Rajaraja to add a short account of his military achievements at the beginning of every one of his inscriptions had been his own. His successors evidently followed his example and have left us more or less complete records of their conquests. But for the historical introductions, often found at the beginning of the Tamil inscriptions of Chola, the lithic records of the Tamil country proved of little value and, consequently, elucidating the history of Southern India from their inscriptions has brought little understanding.

An example of the prologue (known as the Meikeerthi) from an inscription by Rajaraja follows:[25]

ஸ்வஸ்திஸ்ரீ் திருமகள் போல பெருநிலச் செல்வியுந் தனக்கேயுரிமை பூண்டமை மனக்கொளக் காந்தளூர்ச் சாலைக் களமறூத்தருளி வேங்கை நாடும் கங்கைபாடியும் நுளம்பபாடியும் தடிகை பாடியும் குடமலை நாடும் கொல்லமும் கலிங்கமும் எண்டிசை புகழ்தர ஈழ மண்டலமும் இரட்டபாடி ஏழரை இலக்கமும் திண்டிறல் வென்றி தண்டால் கொண்டதன் பொழில் வளர் ஊழியுள் எல்லா யாண்டிலும் தொழுதகை விளங்கும் யாண்டே செழிஞரை தேசுகொள் ஸ்ரீ்கோவிராஜராஜகேசரி பந்மரான ஸ்ரீராஜராஜ தேவர்

Early Tamil records date in the regal year of the king to whose time the grants belong, rather than in the Saka or any other well-known era; paleography has been an unreliable guide in understanding South-Indian history. With the help of the names of contemporary kings of other dynasties mentioned in the historical introductions of the Tamil inscriptions, archaeologists can fix the approximate dates of most of the Chola kings. Consequently, the service, which Rajaraja has rendered to epigraphists in introducing a brief account of his military achievements at the beginning of his stone inscriptions, has been immense.

The historical side of Rajaraja’s intellectual nature has been further manifested in the order he issued to have all the grants made to the Thanjavur temple engraved on stone. Rajaraja had been meticulous about recording his achievements, and equally diligent in preserving the records of his predecessors. For instance, an inscription of his reign found at Tirumalavadi near Thruchi records an order of the king to rebuild the central shrine of the Vaidyanatha temple at the place and, before pulling down the walls, the inscriptions engraved on them should be copied in a book. He ordered the records re-engraved on the walls from the book after the rebuilding completion.

Religious Policy

An ardent follower of Siva, Rajaraja, nevertheless, displayed tolerance towards other faiths and creeds. He had several temples for Vishnu constructed. He also encouraged the construction of the Buddhist Chudamani Vihara at the request of the Srivijaya king Sri Maravijayatungavarman. Rajaraja dedicated the proceeds of the revenue from the village of Anaimangalam towards the upkeep of that Vihara.

Personal Life and Family

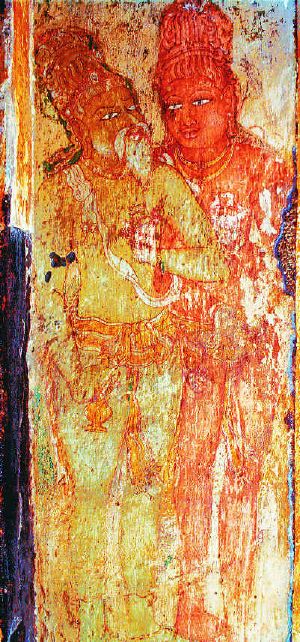

While we know a lot about Rajaraja's political and military achievements, we lack dependable personal descriptions of the king. Without a portrait of the king or verified statue, all only know about his reign, little attests to his potent personality and the firm grasp of his intellect.

Rajaraja had been born Arulmozhivarman, the third child of Parantaka Sundara Chola. His elder brother Aditya II died by assassination in c. 969 C.E. Rajaraja spent a lot of time in the company of Kundavai, his elder sister, and must have much admired her. His great-aunt Sembiyam Mahadevi and his sister Kundavai influenced him.[26] Kundavai married Vandiyadevar, a Bana prince. Kundavai spent her later life in Tanjore with her younger brother and she even survived him. We may suppose that Rajaraja entertained a high regard for her and that she exercised considerable influence over him and contributed in no small degree to the formation of his character.

Rajaraja had a number of wives, but apparently only a few children. The names of Vanavanmahadevi, Lokamahadevi, Cholamahadevi, Trailokyamahadevi, Panchavanmahadevi, Abhimanavalli, Iladamadeviyar (Latamahadevi) and Prithivimahadevi had been inscribed in the Tanjore Temple. Panchavanmahadevi assisted Rajaraja in day-to-day decision makings in the rule. Each of them set up a number of images in the Rajarajesvara temple and made gifts to them. Lokamahadevi probably had been the chief queen. She built the shrine called Uttara-Kailasa in the Panchanadesvara temple at Tiruvaiyaru near Thanjavur and made many gifts to it. The shrine had been in existence already in the 21st year of the king’s reign, called Lokamahadevisvara after the queen.

Vanavan Maha Devi, Princess of Velir, had been the mother of Rajendra I, the only known son of Rajaraja. Rajaraja must have had at least three daughters, of which two have been recorded: Kundavi, who married the Eastern Chalukya prince Vimaladitya and the second daughter Madevadigal, who embraced Buddhism and abstained from marriage. Rajaraja died in 1014 C.E., succeeded by Rajendra Chola I.

References in Popular Tamil Fiction

- Rajaraja Cholan - Drama, written by Kalaimamani Aru. Ramanathan, called as Kathal Ramanathan. (TKS Group made numerous Stage Shows on this Drama and later made into a movie acted by Shivaji Ganesan). The Drama has been published as a book by Prema Pirasuram, Chennai-24, used in South Indian Universities.

- Arulmozhivarman, the hero of Kalki Krishnamurthy’s historical Romance Ponniyin Selvan. The heart of the story revolves around the mysteries surrounding the assassination of Aditya II and the subsequent accession of Uttama to the Chola throne. Kalki imagines Arulmozhi sacrificing his rightful claim to the throne by crowning Uttama during his own coronation.

- Balakumaran has also written the story Udaiyar based on the life of Rajaraja Chola. While Kalki's novel describes his life at his youth at the time of the death of Aditya Karikala, Balakumaran deals with Rajaraja Chola's life after he becomes the emperor.

- In January 2007, Kaviri mainthan - a novel set in the Chola period and a sequel to Ponniyin Selvan written by Anusha Venkatesh, published by The Avenue Press.

- Sujatha wrote a novel "Kandalur Vasanthakumaran Kathai," dealing with the situations leading to his war at the Kandhalur, a sea port.

Notes

- ↑ KAN Sastri, A History of South India. (New Delhi: Oxford University Press, 2000), 163

- ↑ ibid. 163

- ↑ ibid., 163

- ↑ E. Hultzsch, "South Indian Inscriptions," Vol.III.[1]Archaeological Survey of India. accessdate 2007-05-18

- ↑ Sastri (2000), 164

- ↑ KAN Sastri. The Colas. (Madras: University of Madras, 1984)

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India. South Indian Inscriptions, Volume 2 1991 " … until the eighth year of his reign c. A.D. 994 he did not undertake any expedition. During this period he was probably engaged in recruiting an efficient army and otherwise preparing himself for the struggle, which he must have thought he should undertake before the Chola power and prestige could be restored." [2]accessdate 2007-05-24

- ↑ Sastri, (1984)

- ↑ Prithwis Chandra Chakravarti. "Naval Warfare in ancient India" The Indian Historical Quarterly 4 (December 1930)(4): 645-664 "The naval supremacy of the Colas continued under the immediate successors of Rajendra. Rajadhiraja, as stated above, not only defeated and destroyed the Cera fleet at Kandalur but sent out his squadrons on an expedition against Ceylon."

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India. South Indian Inscriptions, Volume 2. 1991. [3]www.whatisindia.com. accessdate 2007-05-24

- ↑ Sastri (2000)

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India. South Indian Inscriptions, Volume 2 1991. "Having already overcome the Chera king, probably while destroying the ships at Kandalur or in the war against the Pandyas, Rajaraja assumed the title Mummudi-Chola, i.e., “the Chola king who wears three crowns, viz., the Chera, Chola and Pandya crows” which occurs first in an inscription of the 14th year at Melpadi in the North Arcot district." [4] accessdate 2007-05-24

- ↑ Sastri, 1984

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India. South Indian Inscriptions, Volume 2. 1991. "A place named Udagai is mentioned in connection with the conquest of the Pandyas. The Kalingattu-Parani refers to the “storming of Udagai” in the verse, which alludes to the reign of Rajaraja. The Kulottunga-Soran-ula also mentions the burning of Udagai. This was probably an important stronghold in the Pandya country, which the Chola king captured." [5]www.whatisindia.com. accessdate 2007-05-24

- ↑ Sastri 1984

- ↑ Archaeological Survey of India. South Indian Inscriptions, Volume 2. 1991. "The Kulottunga-Soran-ula also refers to the same Chola king who “cut off eighteen heads and set fire to Udagai.” The conquest of Malai-nadu and the burning of Udagai refer evidently to the reign of Rajarajadeva, but it does not appear when he cut the heads of eighteen princes." [6]www.whatisindia.com. accessdate 2007-05-24

- ↑ Sastri (1984)

- ↑ Vincent Arthur Smith. The Early History of India. (The Clarendon press, 1904), 336-358

- ↑ 'Rajaraja is supposed to have conquered twelve thousand old isands... a phrase meant to indicate the Maldives -John Keay. India, a History. (London: Harper Collins Publishers, 2000), 215

- ↑ Kearney, 70

- ↑ Sastri, (1984)

- ↑ Geeta Vasudevan. Royal Temple of Rajaraja: An Instrument of Imperial Cola Power. (Abhinav Publications, 2003), 44

- ↑ Ibid., 46

- ↑ Ibid., 62-63

- ↑ varalaaru.com[7] www.varalaaru.com.

- ↑ Vasudevan (2003), 103

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Chakravarti, Prithwis Chandra. "Naval Warfare in ancient India" The Indian Historical Quarterly 4 (December 1930)(4)

- Kearney, Milo. 2003. The Indian Ocean in World History. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415312779

- Keay, John. 2000. India, a History. London: Harper Collins Publishers. ISBN 0006387845

- Nilakanta Sastri, K.A. 2000. A History of South India. New Delhi: Oxford University Press. ISBN 01956606868

- __________. 1984. The Colas. Madras: University of Madras, OCLC 2025491

- Smith, Vincent Arthur (1904). The Early History of India. The Clarendon press

- Vasudevan, Geeta. 2003. Royal Temple of Rajaraja: An Instrument of Imperial Cola Power. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 0006387845

External Links

All links retrieved December 7, 2022.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.