Ghaznavid Empire

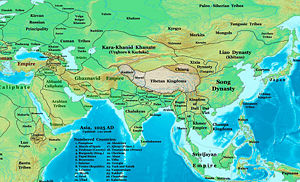

The Ghaznavid Empire was a KhorÄáčŁÄnian[1] founded by a dynasty of Turkic mamluk (soldier-slaves) origin, which existed from 975 to 1187. It was centered in Ghazni, a city in present day Afghanistan, and ruled much of Persia, Transoxania, and parts of present day Pakistan. Due to the political and cultural influence of their predecessors - that of the Persian áčąÄmÄnÄ« dynasty - the originally Turkic Ghaznavids had become thoroughly Persianized.[2][3][4][5][6].

Early History

The dynasty was founded by Sebuktigin when he succeeded to the ruler-ship of territories centered around the city of Ghazni from his father-in-law, Alp Tigin, a break-away ex-general of the áčąÄmÄnÄ« sultans. Sebuktigin's son, Shah Mahmoud, expanded the empire in the region that stretched from the Oxus river to the Indus Valley and the Indian Ocean; and in the west it reached Rayy and Hamadan. Under the reign of Mas'ud I it experienced major territorial losses. It lost its western territories to the Seljuqs in the Battle of Dandanaqan resulting in a restriction of its holdings to Afghanistan, Balochistan and the Punjab. In 1151, Sultan Bahram Shah lost Ghazni to Ala'uddin Hussain of Ghor and the capital was moved to Lahore until its subsequent capture by the Ghurids in 1186. For two centuries, the Ghaznavid Empire, the first significant Muslim power in Central Asia, deliberately propagated Islam among the peoples of the Indian sub-continent. Eventually, Muslims became the second-largest religious community. The nation-states of Pakistan and Bangladesh have their origins in the Ghaznavid legacy. For the people who lived under Ghaznavid rule, life was stable and secure. Maintaining strong links with the Abbasids in Baghdad, too, the Empire and its subjects were self-consciously part of a wider polity. Their purpose was to encourage obedience to God's will, so that the whole earth could become the "abode of peace," even if violence was used to establish their ideal social order.

Rise to Power

Two military families arose from the Turkic Slave-Guards of the Samanidsâthe Simjurids and Ghaznavidsâwho ultimately proved disastrous to the Samanids. The Simjurids received land grant awarded with a rank or title, called an appanage, in the Kohistan region of eastern Khorasan. Alp Tigin founded the Ghaznavid fortunes when he established himself at Ghazna (modern Ghazni, Afghanistan) in 962. He and Abu al-Hasan Simjuri, as Samanid generals, competed with each other for the governorship of Khorasan and control of the Samanid empire by placing on the throne emirs they could dominate when Abdul Malik I of Samanid died in 961. But when the Samanid Emir Abdul Malik I died in 961 C.E. it created a succession crisis between Abdul Malik's brothers. A court party instigated by men of the scribal classâcivilian ministers as contrasted with Turkic generalsârejected Alp Tigin's candidate for the Samanid throne. Mansur I was installed, and Alp Tigin prudently retired to his fief of Ghazna. The Simjurids enjoyed control of Khorasan south of the Oxus but were hard-pressed by a third great Iranian dynasty, the Buwayhids, and were unable to survive the collapse of the Samanids and the rise of the Ghaznavids.

The struggles of the Turkic slave generals for mastery of the throne with the help of shifting allegiance from the court's ministerial leaders both demonstrated and accelerated the Samanid decline. Samanid weakness attracted into Transoxania the Qarluq Turks, who had recently converted to Islam. They occupied Bukhara in 992 to establish in Transoxania the Qarakhanid, or Ilek Khanid, dynasty. Alp Tigin had been succeeded at Ghazna by SebĂŒktigin (died 997). SebĂŒktigin's son Mahmud made an agreement with the Qarakhanids whereby the Oxus was recognized as their mutual boundary.

Expansion and Golden Age

Saboktekin made himself lord of nearly all the present territory of Afghanistan and of the Punjab by conquest of Samanid and Shahi lands. In 997, Mahmud, the son of SebĂŒk Tigin, succeeded his father upon his death, and with him Ghazni and the Ghaznavid dynasty have become perpetually associated. He completed the conquest of Samanid, Shahi lands, the Ismaili Kingdom of Multan, Sindh as well as some Buwayhid territory. Under him all accounts was the golden age and the height of the Ghaznavid Empire. Mahmud carried out 17 expeditions through northern India establishing his control and setting up tributary states. His raids also resulted in the looting of a great deal of plunder. From the borders of Kurdistan to Samarkand, from the Caspian Sea to the Yamuna, he established his authority. Recognizing the authority of the Abbasid caliph, Mahmud used both titles "Emir" and "Sultan".[7] When he turned his attention towards India, he was encouraged by the caliph to spread Islam among its non-Muslim population. He vowed to raid India annually in order to spread Islam there. Thus, "the Ghaznavids are generally credited with launching Islam into Hindu-dominated India."[8]

The wealth brought back from the Indian expeditions to Ghazni was enormous, and contemporary historians (e.g. Abolfazl Beyhaghi, Ferdowsi) give glowing descriptions of the magnificence of the capital, as well as of the conqueror's munificent support of literature. Mahmud died in (1030). Even though there was some revival of importance under Ibrahim (1059-1099), the empire never reached anything like the same splendor and power. It was soon overshadowed by the Seljuqs of Iran.

Decline

Mahmud's son Mas'ud was unable to preserve the empire and following a disastrous defeat at the Battle of Dandanaqan in (1040) lost all the Ghaznavid lands in Iran and Central Asia to the Seljuks and plunged the realm into a "Time of troubles".[1] Mas'ud's son Ibrahim who re-established a truncated empire on a firmer basis by arriving at a peace agreement with the Seljuks and a restoration of cultural and political linkages.[1] Under Ibrahim and his successors the empire saw a period of peace and stability. The loss of its western land led to increased raids across Northern India to plunder the land, where it faced stiff resistance from Rajput rulers such as the Paramara of Malwa and the Gahadvala of Kannauj.[1] Signs of weakness in the state became apparent when Masud III died in 1115 with internal strife between his sons ending with the ascension of Sultan Bahram Shah as a Seljuk Vassal.[1] Sultan Bahram Shah, was the last Ghaznavid King ruling Ghazni, the first and main Ghaznavid capital. Ala'uddin Hussain, a Ghorid King, conquered the city of Ghazni in 1151, for the revenge of his brother's death. He razed all the city, and burned it for seven days, after which he got famous as "JahÄnsoz" (World Burner). Ghazni was restored to the Ghaznavids by the intervention of the Seljuks who came to Behram's aid.[1] Ghaznavid struggles with the Ghurids continued in the subsequent years as they nibbled away at Ghaznavid territory and Ghazni and Zabulistan was lost a group of Oghuz Turks before captured by the Gurids.[1] Ghaznavid power in northern India continued until the conquest of Lahore from Khusrau Malik in 1186.[1]

Legacy

The Ghaznavid Empire grew to cover much of present-day Iran, Afghanistan, and northwest India and Pakistan, and the Ghaznavids are generally credited with launching Islam into Hindu-dominated India. In addition to the wealth accumulated through raiding Indian cities, and exacting tribute from Indian Rajas the Ghaznavids also benefited from their position as an intermediary along the trade routes between China and the Mediterranean Sea. They were however unable to hold power for long and by 1040 the Seljuks had taken over their Persian domains and a century later the Ghurids took over their remaining sub-continental lands. The Ghaznavid Empire was the first significant Muslim power in Central Asia, responsible for spreading Islam into the Indian Sub-Continent. This permanently changed the dynamics of Indian society. Islam became India's second-largest religion. The modern nation-states of Pakistan and of Bangladesh can trace their Muslim heritage back to Ghaznavid raids into Indian territory.

Culture

Although the Ghaznavids were of Turkic origin and their military leaders were generally of the same stock, as a result of the original involvement of Sebuktigin and Mahmud of Ghazni in Samanid affairs and in the Samanid cultural environment, the dynasty became thoroughly Persianized, so that in practice one cannot consider their rule over Iran one of foreign domination. In terms of cultural championship and the support of Persian poets, they were far more Persian than the ethnically Iranian Buyids rivals, whose support of Arabic letters in preference to Persian is well known.[9]

- Alptigin (963-977)

- SebĂŒk Tigin, or Sebuktigin (Abu Mansur) (977-997)

- Ismail of Ghazni (997-998)

- Mahmud of Ghaznavid (Yamin ud-Dawlah) (998-1030)

- Mohammad Ghaznavi (Jalal ud-Dawlah) (1030-1031)

- Mas'ud I of Ghazni (Shihab ud-Dawlah) (1031â1041)

- Mohammad Ghaznavi (Jalal ud-Dawlah (second time) (1041)

- Maw'dud Ghaznavi (Shihab ud-Dawlah) (1041-1050)

- Mas'ud II (1050)

- Ali (Baha ud-Dawlah) (1050)

- Abd ul-Rashid (Izz ud-Dawlah) (1053)

- ToÄrĂŒl (Tughril) (Qiwam ud-Dawlah) (1053)

- Farrukhzad (Jamal ud-Dawlah) (1053-1059)

- Ibrahim (Zahir ud-Dalah) (1059-1099)

- Mas'ud III (Ala ud-Dawlah) (1099-1115)

- Shirzad (Kemal ud-Dawlah) (1115)

- Arslan Shah (Sultan ud-Dawlah) (1115-1118)

- Bahram Shah (Yamin ud-Dawlah ) (1118-1152)

- Khusrau Shah (Mu'izz ud-Dawlah) (1152-1160)

- Khusrau Malik (Taj ud-Dawlah) (1160-1187)

Notes

- â 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 Clifford Edmund Bosworth, 2006. Ghaznavids Encyclopaedia Iranica. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- â M.A. Amir-Moezzi, 2005. Shahrbanu. Encyclopaedia Iranica "⊠here one might bear in mind that non-Persian dynasties such as the Ghaznavids, Saljuqs and Ilkhanids were rapidly to adopt the Persian language and have their origins traced back to the ancient kings of Persia rather than to Turkish heroes or Muslim saints âŠ"

- â B. Spuler, 1970. "The Disintegration of the Caliphate in the East," 143-174 in P.M. Holt, Ann K.S. Lambton, and Bernard Lewis. 1970. Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. IA: The Central Islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521291354), 147: "One of the effects of the renaissance of the Persian spirit evoked by this work was that the Ghaznavids were also Persianized and thereby became a Persian dynasty."

- â Anatoly M. Khazanov, and AndrĂ© Wink. 2001. Nomads in the Sedentary World. (Richmond, VA: Curzon. ISBN 9780700713691), 12: "The Persianized Ghaznavids and some later dynasties, just like their mamluk-type elite troops, were of Turkic origin"

- â David Christian. 1998. A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia. (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing. ISBN 9780631208143), 370: "Though Turkic in origin and, apparently in speech, Alp Tegin, Sebuk Tegin and Mahmud were all thoroughly Persianized"

- â Robert L. Canfield, 1991. Turko-Persia in historical perspective. (Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521390941), 8: "The Ghaznavids (989-1149) were essentially Persianized Turks who in manner of the pre-Islamic Persians encouraged the development of high culture."

- â Emir is "commander"; Sultan implies that authority has been delegated.

- â The Islamic World to 1600. The University of Calgary. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

- â Ehsan Yarshater, 2006. Iran: Formation of Local Dynasties Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved September 18, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Bosworth, Clifford Ed. The Ghaznavids: Their Empire in Afghanistan and Eastern Iran 994â1040. Edinburgh, UK: Edinburgh University Press, 1963.

- Bosworth, Clifford Ed. The Later Ghaznavids: Splendour and Decay, The Dynasty in Afghanistan and Northern India 1040â1186. New York, NY: Columbia University Press, 1977. ISBN 978-0231044288.

- Canfield, Robert L. Turko-Persia in historical perspective. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 978-0521390941.

- Christian, David. A History of Russia, Central Asia and Mongolia. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing, 1998. ISBN 978-0631208143.

- Holt, P.M., Ann K.S. Lambton, and Bernard Lewis. Cambridge History of Islam, Vol. IA: The Central Islamic Lands from Pre-Islamic Times to the First World War. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1970. ISBN 978-0521291354.

- The Islamic World to 1600. The University of Calgary, 1998.

- Khazanov, Anatoly M., and André Wink. Nomads in the Sedentary World. Richmond, VA: Curzon, 2001. ISBN 978-0700713691.

- Marcinkowski, M. Ismail. Persian Historiography and Geography: Bertold Spuler on Major Works Produced in Iran, the Caucasus, Central Asia, India and Early Ottoman Turkey. Singapore, SG: Pustaka Nasional, 2003. ISBN 978-9971774882.

- This article incorporates text from the EncyclopĂŠdia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved May 21, 2024.

- Columbia Encyclopedia (Sixth Edition) - Mahmud of Ghazna.

- Encylopaedia Britannica (Online Edition) - Mahmud.

- Encyclopaedia Britannica (Online Edition) - Ghaznavid Dynasty.

- Afghan secrets revealed on Google Earth.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.