Benjamin Bloom

Benjamin Bloom (February 21, 1913 - September 13, 1999) was an American educational psychologist who made significant contributions to the classification of educational objectives and the theory of mastery learning. His research, which showed that educational settings and home environments can foster human potential, transformed education. Bloom developed a "taxonomy of educational objectives" which classified the different learning objectives and skills that educators set for students. Bloom divided educational objectives into three "domains:" Affective, Psychomotor, and Cognitive. It is hierarchical, like other taxonomies, meaning that learning at the higher levels is dependent on having attained prerequisite knowledge and skills at lower levels. Bloom intended that the Taxonomy motivate educators to focus on all three domains, creating a more holistic form of education.

Bloom also carried out significant research on mastery learning, showing that it is not innate giftedness that allows one to succeed, but rather hard work. His studies showed that the most successful in their fields all put in at least ten years of dedicated effort before achieving significant recognition. Bloom's work stressed that attainment was a product of learning, and learning was influenced by opportunity and effort. It was a powerful and optimistic conception of the possibilities that education can provide, and one that Bloom was able to bring into practice. Based on his efforts, evaluation methods and concepts were radically changed. His activism also supported the creation of the Head Start program that provides support to pre-school age children of low-income families, giving them opportunities to begin a life of learning and consequent achievement. However, his research led him to realize that early experiences within the family are the most significant in providing a good foundation for learning.

Life

Benjamin S. Bloom was born on February 21, 1913, in Lansford, Pennsylvania.

As a youth, Bloom had an insatiable curiosity about the world. He was a voracious reader and a thorough researcher. He read everything and remembered well what he read. As a child in Lansford, Pennsylvania, the librarian would not allow him to return books that he had checked out earlier that same day until he was able to convince her that he had, indeed, read them completely.

Bloom was especially devoted to his family (his wife, Sophie, and two sons), and his nieces and nephews. He had been a handball champion in college and taught his sons both handball and Ping-Pong, chess, how to compose and type stories, as well as to invent.

He received a bachelorâs and masterâs degree from Pennsylvania State University in 1935, and a Ph.D. in Education from the University of Chicago in March 1942. He became a staff member of the Board of Examinations at the University of Chicago in 1940 and served in that capacity until 1943, at which time he became university examiner, a position he held until 1959.

He served as educational adviser to the governments of Israel and India.[1]

What Bloom had to offer his students was a model of an inquiring scholar, someone who embraced the idea that education as a process was an effort to realize human potential, and even more, it was an effort designed to make potential possible. Education was an exercise in optimism. Bloomâs commitment to the possibilities of education provided inspiration for many who studied with him.[2]

Benjamin Bloom died Monday, Sept. 13, 1999 in his home in Chicago. He was 86.

Work

Benjamin Bloom was an influential academic educational psychologist. His main contributions to the area of education involved mastery learning, his model of talent development, and his Taxonomy of Educational Objectives in the cognitive domain.

He focused much of his research on the study of educational objectives and, ultimately, proposed that any given task favors one of three psychological domains: Cognitive, affective, or psychomotor. The cognitive domain deals with the ability to process and utilize (as a measure) information in a meaningful way. The affective domain is concerned with the attitudes and feelings that result from the learning process. Lastly, the psychomotor domain involves manipulative or physical skills.

Bloom headed a group of cognitive psychologists at the University of Chicago who developed a taxonomic hierarchy of cognitive-driven behavior deemed to be important to learning and measurable capability. For example, an objective that begins with the verb "describe" is measurable but one that begins with the verb "understand" is not.

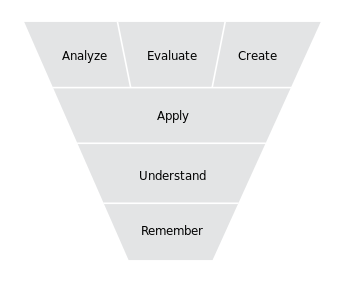

His classification of educational objectives, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain, published in 1956, addresses cognitive domain versus the psychomotor and affective domains of knowledge. It was designed to provide a more reliable procedure for assessing students and the outcomes of educational practice. Bloomâs taxonomy provides structure in which to categorize instructional objectives and instructional assessment. His taxonomy was designed to help teachers and Instructional Designers to classify instructional objectives and goals. The foundation of his taxonomy was based on the idea that not all learning objectives and outcomes are equal. For example, memorization of facts, while important, is not the same as the learned ability to analyze or evaluate. In the absence of a classification system (a taxonomy), teachers and Instructional Designers may choose, for example, to emphasize memorization of facts (which make for easier testing) than emphasizing other (and likely more important) learned capabilities.

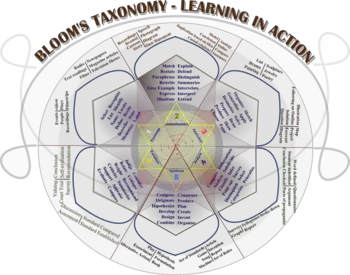

Taxonomy of educational objectives

Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives is a classification of the different objectives and skills that educators set for students (learning objectives). Bloom divided educational objectives into three "domains:" Affective, Psychomotor, and Cognitive. This taxonomy is hierarchical, meaning that learning at the higher levels is dependent on having attained prerequisite knowledge and skills at lower. Bloom intended that the Taxonomy motivate educators to focus on all three domains, creating a more holistic form of education.

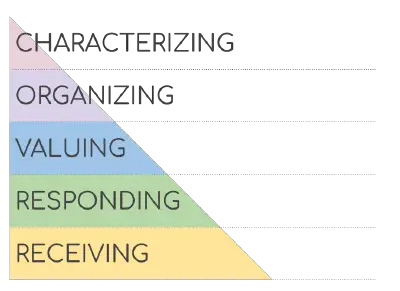

Affective

Skills in the affective domain describe the way people react emotionally and their ability to feel another living thing's pain or joy. Affective objectives typically target the awareness and growth in attitudes, emotion, and feelings. There are five levels in the affective domain moving through the lowest order processes to the highest:

- Receiving

- The lowest level; the student passively pays attention. Without this level no learning can occur.

- Responding

- The student actively participates in the learning process, not only attends to a stimulus, the student also reacts in some way.

- Valuing

- The student attaches a value to an object, phenomenon, or piece of information.

- Organizing

- The student can put together different values, information, and ideas and accommodate them within his/her own schema; comparing, relating, and elaborating on what has been learned.

- Characterizing

- The student has held a particular value or belief that now exerts influence on his/her behavior so that it becomes a characteristic.

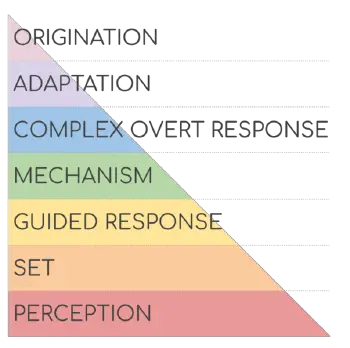

Psychomotor

Skills in the psychomotor domain describe the ability to physically manipulate a tool or instrument like a hand or a hammer. Psychomotor objectives usually focus on change and/or development in behavior and/or skills.

Bloom and his colleagues never created subcategories for skills in the psychomotor domain, but since then other educators have created their own psychomotor taxonomies.[3] For example, Harrow wrote of the following categories:

- Reflex movements

- Reactions that are not learned.

- Fundamental movements

- Basic movements such as walking, or grasping.

- Perception

- Response to stimuli such as visual, auditory, kinesthetic, or tactile discrimination.

- Physical abilities

- Stamina that must be developed for further development such as strength and agility.

- Skilled movements

- Advanced learned movements as one would find in sports or acting.

- No discursive communication

- Effective body language, such as gestures and facial expressions.[4]

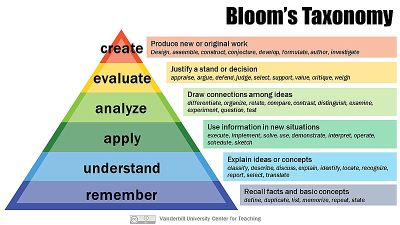

Cognitive

Skills in the cognitive domain revolve around knowledge, comprehension, and "thinking through" a particular topic. Traditional education tends to emphasize the skills in this domain, particularly the lower-order objectives. There are six levels in the taxonomy, moving through the lowest order processes to the highest:

- Knowledge

- Exhibit memory of previously-learned materials by recalling facts, terms, basic concepts and answers

- Knowledge of specificsâterminology, specific facts

- Knowledge of ways and means of dealing with specificsâconventions, trends and sequences, classifications and categories, criteria, methodology

- Knowledge of the universals and abstractions in a fieldâprinciples and generalizations, theories and structures

- Comprehension

- Demonstrative understanding of facts and ideas by organizing, comparing, translating, interpreting, giving descriptions, and stating main ideas

- Translation

- Interpretation

- Extrapolation

- Application

- Using new knowledge. Solve problems to new situations by applying acquired knowledge, facts, techniques, and rules in a different way

- Analysis

- Examine and break information into parts by identifying motives or causes. Make inferences and find evidence to support generalizations

- Analysis of elements

- Analysis of relationships

- Analysis of organizational principles

- Synthesis

- Compile information together in a different way by combining elements in a new pattern or proposing alternative solutions

- Production of a unique communication

- Production of a plan, or proposed set of operations

- Derivation of a set of abstract relations

- Evaluation

- Present and defend opinions by making judgments about information, validity of ideas or quality of work based on a set of criteria

- Judgments in terms of internal evidence

- Judgments in terms of external criteria

Some critics of Bloom's Taxonomy's (cognitive domain) admit the existence of these six categories, but question the existence of a sequential, hierarchical link.[5] Also, the revised edition of Bloom's taxonomy moved Synthesis to a higher position than Evaluation. Some consider the three lowest levels as hierarchically ordered, but the three higher levels as parallel. Others say that it is sometimes better to move to Application before introducing Concepts. This thinking would seem to relate to the method of Problem Based Learning.

Studies in early childhood

In 1964, Bloom published Stability and Change in Human Characteristics. That work, based on a number of longitudinal studies, led to an upsurge of interest in early childhood education, including the creation of the Head Start program. He was invited to testify to the Congress of the United States about the importance of the first four years of the childâs life as the critical time to promote cognitive development. His testimony had an impact in promoting and maintaining funding for this program. He argued that human performance was often a reflection of social privilege and social class. Children who enjoyed the benefits of habits, attitudes, linguistic skills, and cognitive abilities available to the more privileged members of society were likely to do well at school. To confer additional privileges on those who already had a head start was to create an array of inequities that would eventually exact extraordinary social costs. He further stated that since environment plays such an important role in providing opportunity to those already privileged, it seemed reasonable to believe that by providing the kind of support that the privileged already enjoyed to those who did not have it, a positive difference in their performance would be made.

Bloom showed that many physical and mental characteristics of adults can be predicted through testing done while they are still children. For example, he demonstrated that 50 percent of the variations in intelligence at age 17 can be estimated at age four. He also found that early experiences in the home have a great impact on later learning, findings that caused him to rethink the value of the Head Start program.

Bloom summarized his work in a 1980 book titled, All Our Children Learning, which showed from evidence gathered in the United States and abroad that virtually all children can learn at a high level when appropriate practices are undertaken in the home and school.

In the later years of his career, Bloom turned his attention to talented youngsters and led a research team that produced the book, Developing Talent in Young People, published in 1985.

Mastery learning

In 1985, Bloom conducted a study suggesting that at least ten years of hard work (a "decade of dedication"), regardless of genius or natural prodigy status, is required to achieve recognition in any respected field.[6] This shows starkly in Bloom's 1985 study of 120 elite athletes, performers, artists, biochemists, and mathematicians. Every single person in the study took at least a decade of hard study or practice to achieve international recognition. Olympic swimmers trained for an average of 15 years before making the team; the best concert pianists took 15 years to earn international recognition. Top researchers, sculptors, and mathematicians put in similar amounts of time.

Bloomâs research on giftedness undermines its typical conception. Giftedness typically connotes the possession of an ability that others do not have. A gift suggests something special that is largely the result of a genetically conferred ability. While Bloom recognized that some individuals had remarkable special abilities, the use of such a model of human ability converted the educatorsâ role from inventing ways to optimize human aptitude into activities mainly concerned with matters of identification and selection. The latter process was itself predicated on the notion that cream would rise to the top. The educatorâs mission, Bloom believed, was to arrange the environmental conditions to help realize whatever aptitudes individuals possessed. Bloom discovered that all children can learn at a high level when appropriate practice, attention, and support are undertaken in the home and school. Champion tennis players, for example, profited from the instruction of increasingly able teachers of tennis during the course of their childhood. Because of this and the amount of time and energy they expended in learning to play championship tennis, they realized goals born of guidance and effort rather than raw genetic capacity. Attainment was a product of learning, and learning was influenced by opportunity and effort. It was a powerful and optimistic conception of the possibilities that education can provide.

Bloomâs message to the educational world was to focus on target attainment and to abandon a horse-race model of schooling that has as its major aim the identification of those who are swiftest. Speed is not the issue, he argued, achievement or mastery is, and it is that model that should be employed in trying to develop educational programs for the young. Mastery learning was an expression of what Bloom believed to be an optimistic approach to the realization of educational goals. When well implemented, approximately 80 percent of the students in mastery learning classes earned As and Bs, compared with only 20 percent in control classes.[7]

Some of the effects of mastery learning include:

- Increased student self-assurance

- Reduced competition and encouraged cooperation among students;

that is, students were enabled to help one another

- Assessments as learning tools rather than official grades

- Second chance at success for students

Legacy

Bloom was considered a world guru of education. He was first involved in world education when the Ford Foundation sent him to India in 1957, to conduct a series of workshops on evaluation. This led to a complete revision of the examination system in India. It was also the beginning of his work as an educational adviser and consultant to countries around the world. He also served as educational adviser to the governments of Israel and numerous other nations. In the U.S. and abroad, Bloom was instrumental in shifting the instructional emphasis from teaching facts to teaching students how to use the knowledge they had learned. He revolutionized education through his thinking that, backed by significant research evidence, that what any person can learn, all can learn, except perhaps for the lowest one or two percent of students.

Bloomâs scholarship in education was complemented by his activism. He played a major role in creating the International Association for the Evaluation of Educational Achievement (IEA) and in organizing the International Seminar for Advanced Training in Curriculum Development, held in Granna, Sweden, in the summer of 1971. His work in the IEA, since its inception over thirty years ago, has had a significant impact on the efforts being made internationally to improve studentsâ learning in the dozens of countries that are members of the IEA.

In the Department of Education at the University of Chicago, he developed the MESA (Measurement, Evaluation, and Statistical Analysis) program. This program was designed to prepare scholars who had the quantitative and analytical skills to think through in great depth what needed to be addressed in order to design genuinely informative and educationally useful evaluation practices. His commitment to the possibilities and potential of education as an exercise in optimism infused his views about how young scholars should be prepared in the field of evaluation. He also served as chairman of the research and development committees of the College Entrance Examinations Board and was elected President of the American Educational Research Association in 1965. Scholars recognized the stature of this extraordinary man and honored him with appointments, honorary degrees, medals, and election to office. Elliot W. Eisner wrote of Benjamin Bloom:

The field of education, and more important, the lives of many children and adolescents are better off because of the contributions he made.[2]

Major publications

- Bloom, Benjamin S. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain. Addison-Wesley Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0582280106

- Bloom, Benjamin S. 1956. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals. Longman. ISBN 978-0679302094

- Bloom, Benjamin S. 1980. All Our Children Learning. New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 9780070061187

- Bloom, B. S., & Sosniak, L.A. 1985. Developing Talent in Young People. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 9780345319517

Notes

- â Kat Pugh, Benjamin Bloom's impact on education October 28, 2014. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- â 2.0 2.1 Elliot W. Eisner, Benjamin Bloom Prospects: The Quarterly Review of Comparative Education Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education, XXX(3) (September 2000). Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- â Donald R. Clark, Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning Domains Big Dog and Little Dog's Performance Juxtaposition, January 12, 2015. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- â Anita Harrow, A Taxonomy of Psychomotor Domain: A Guide for Developing Behavioral Objectives (New York: David McKay, 1972, ISBN 978-0679302124).

- â Richard W. Paul, Critical Thinking: What every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World (Rohnert Park, CA: Sonoma State University Press, 1993, ISBN 978-0944583074).

- â David Dobbs, How to be a genius The New Scientist Online Magazine, September 13, 2006. Retrieved April 24, 2023.

- â Thomas R. Guskey, Benjamin S. Bloom Portraits of an Educator (Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2005, ISBN 1578862434).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Anderson, Lorin W., and David R. Krathwohl (eds.). A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and AssessingâA Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Allyn & Bacon, 2000. ISBN 978-0321084057

- Guskey, Thomas R. Benjamin S. Bloom Portraits of an Educator. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Education, 2005. ISBN 1578862434

- Harrow, Anita. A Taxonomy of Psychomotor Domain: A Guide for Developing Behavioral Objectives. New York, NY: David McKay, 1972. ISBN 978-0679302124

- Paul, Richard W. Critical Thinking: What every Person Needs to Survive in a Rapidly Changing World. Rohnert Park, CA: Sonoma State University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0944583074

External links

All links retrieved September 27, 2023.

- Bloom's Taxonomy of Learning Domains

- Bloom, influential education researcher Obituary in The University of Chicago Chronicle.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.