Aikido

| Aikido | |

|---|---|

| Japanese Name | |

| Kanji | åæ°£é |

| Hiragana | ãããã©ã |

| |

Aikido is a modern Japanese budo (martial art), developed by Morihei Ueshiba between the 1920s and the 1960s. Ueshiba was religiously inspired to develop a martial art with a "spirit of peace." Aikido emphasizes using full body movement to unbalance and disable or dominate an attacking opponent. Aikido has a significant spiritual element; students are taught to center themselves and to strive for absolute unity between the mind and body. Training is often free-style and involves engagement with multiple attackers, so that the student learns concentration and fluidity of movement.

Aikido techniques can be practiced with or without weapons, in a variety of positions. Aikido training aims to achieve all-around physical fitness, flexibility, and relaxation. Students learn to face attacks directly, and the confidence which they acquire in doing so extends to many aspects of daily life. Most aikido schools do not hold competitions, because Ueshiba felt that competition was dangerous and detrimental to the development of character.

Ueshibaâs students developed several variations of aikido; the largest organization is still run by his family. Aikido was introduced in France in 1951, and in the United States in 1953. Today aikido is taught in dojos all over the world.

Spirit of Aikido

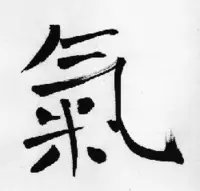

The name aikido is formed of three Japanese characters, ai (å) (union/harmony); ki (æ°) ( universal energy/spirit); and do (é) (way). It can be translated as "the way to union with universal energy" or "the way of unified energy." Another common interpretation of the characters is harmony, spirit and way, so aikido can also mean "the way of spiritual harmony" or "the art of peace." The Japanese word for 'love' is also pronounced ai, although a different Chinese character (æ) is used. In later life, Ueshiba emphasised this interpretation of ai.

Aikido was born out of three enlightenment experiences in which Ueshiba received a divine inspiration that led away from the violent nature of his previous martial training, and towards a "spirit of peace." Ueshiba ultimately said that the way of the warrior is the "way of divine love that nurtures and protects all things."

History

Morihei Ueshiba, also known by practitioners of aikido as O-Sensei ("Great Teacher"), developed aikido mainly from DaitÅ-ryÅ« Aiki-jÅ«jutsu, incorporating training movements such as those for the yari (spear), jo (a short quarterstaff), and perhaps also juken (bayonet). But the strongest influence is that of kenjutsu and in many ways, an aikido practitioner moves as an empty handed swordsman. The aikido strikes shomenuchi and yokomenuchi originated from weapon attacks, and response techniques from weapon disarms. Some schools of aikido do no weapons training at all; others, such as Iwama Ryu usually spend substantial time with bokken, jo, and tanto (knife). In some lines of aikido, all techniques can be performed with a sword as well as unarmed. Some believe there is a strong influence from YagyÅ« Shinkage-ryÅ« on Aikido.

Aikido was first brought to the West in 1951 by Minoru Mochizuki on a visit to France where he introduced aikido techniques to judoka there. He was followed in 1952 by Tadashi Abe, who came as the official Aikikai Honbu representative, remaining in France for seven years. In 1953, Kenji Tomiki toured with a delegation of various martial artists through 15 states in the United States. Later the same year, Koichi Tohei was sent by Aikikai Honbu to Hawaii to set up several dojo. This is considered the formal introduction of aikido to the United States. The United Kingdom followed in 1955, Germany and Australia in 1965. Today there are many aikido dojos offering training throughout the world.

Technique

Aikido incorporates a wide range of techniques which use principles of energy and motion to redirect, neutralize and control attackers.

There is no set form in Aikido. There is no set form, it is the study of the spirit. One must not get caught up in set form, because in doing so, one is unable to perform the function sensitively. In Aikido, first we begin with the cleansing of the ki of one's soul. Following this, the rebuilding of one's spirit is essential. Through the physical body, the performance of kata is that of haku (the lower self). We study kon (the higher self, or spirit). We must advance by harmoniously uniting the higher and lower selves. The higher self must make use of the lower self. (Morihei Ueshiba)

Training

Training is done through mutual technique, where the focus is on entering and harmonizing with the attack, rather than on meeting force with force. Uke, the receiver of the technique, usually initiates an attack against nage (also referred to as tori or shite depending on aikido style), who neutralizes this attack with an aikido technique.

Uke and nage have equally important roles. The role of uke is to be honest and committed in attack, to use positioning to protect himself, and to learn proper technique through the imbalanced feeling created by his attack and the response to it. The role of nage is to blend with and neutralize uke's attack without leaving an opening for further attacks. Simultaneously, the nage will be studying how to create a sense of being centered (balanced) and in control of the application of the aikido technique. Students must practice both uke and nage in order to learn proper technique.

One of the first things taught to new students is how to respond appropriately when an aikido technique is applied, and fall safely to the ground at the correct time. Both tumbling, and later, break-falls are an important part of learning aikido. This assures the uke's safety during class and permits sincere execution of the technique. The word for this skill is ukemi, ("receiving"). The uke actively receives the aikido technique, rather than simply being controlled by the nage.

Because the techniques of aikido can be very harmful if applied too strongly on an inexperienced opponent, the level of practice depends on the ability of uke to receive the technique, as much as it depends on the ability of nage to apply it. When the nage gains control and applies a technique, it is prudent for the uke to fall in a controlled fashion, both to prevent injury and to allow uke to feel the mechanics that make the technique effective. Similarly, it is the responsibility of nage to prevent injury to uke by employing a speed and force of application appropriate for the abilities of uke. Constant communication is essential so that both aikidoka may take an active role in ensuring safe and productive practice.

Movement, awareness, precision, distance and timing are all important to the execution of aikido techniques as students progress from rigidly defined exercises to more fluid and adaptable applications. Eventually, students take part in jiyu-waza (free technique) and randori (freestyle sparring), where the attacks are less predictable. Most schools employ training methods wherein the uke actively attempts to employ counter-techniques, or kaeshi-waza.

Ueshiba did not allow competition in training because some techniques were considered too dangerous and because he believed that competition did not develop good character in students. Most styles of aikido continue this tradition, although Shodokan Aikido began holding competitions shortly after its formation. In the Ki Society there are forms taigi (competitions) held from time to time.

Defense

Aikido techniques are largely designed to keep the attacker off balance and lead his mind. Manipulation of uke's balance by entering is often referred to as "taking the center." It is sometimes said that aikido techniques are only defense, and the attacks that are performed are not really aikido. This claim is debatable, but many aikidoka have the defense techniques as the focus of their training. Much of aikido's repertoire of defenses can be performed either as throwing techniques (nage-waza) or as pins (katame-waza), depending on the situation.

Each technique can be executed in many different ways. For example, a technique carried out in the irimi style consists of movements inward, toward the uke, while those carried out in the tenkan style use outward sweeping motions, and tenshin styles involve a slight retreat from or orbit around the point of attack. An uchi ("inside") style technique takes place towards the front of uke, whereas a soto ("outside") style technique takes place to his side; an omote version of a technique is applied in front of him, an ura version is applied using a turning motion; and most techniques can be performed when either uke or nage (or both) are kneeling. Using less than 20 basic techniques, there are thousands of possible actions depending on the attack and the situation. (Ueshiba claimed that there are 2,664 techniques.)

There are also atemi, or strikes employed during an aikido technique. The role and importance of atemi is a matter of debate in aikido, but it is clear that they were practiced by the founder. Some view atemi as strikes to "vital points" that can be delivered during the course of a technique's application, to increase its effectiveness. Others consider atemi to be methods of distraction, particularly when aimed at the face. For instance, if a movement would expose the aikido practitioner to a counter-blow, he or she may deliver a quick strike to distract the attacker or occupy the threatening limb. (Such a strike will also break the target's concentration, making them easier to throw than if they were able to focus on resisting.) Atemi can be interpreted as not only punches or kicks but also, for instance, striking with a shoulder or a large part of the arm. Some throws are carried out through an unbalancing or abrupt application of atemi.

The use of atemi depends on the aikido organization and the individual dojo. Some dojo teach the strikes that are integral to all aikido techniques as mere distractions, used to make the application of an aikido technique easier; others teach that strikes are to be used for more destructive purposes. Ueshiba himself wrote, while describing the aikido technique shomenuchi ikkyo (the first immobilization technique), "â¦first smash the eyes." Thus, one possible opening movement for ikkyo is a knife-hand thrust towards the face, as though moving to smash uke's eyes, to make the uke block and thus expose his or her arm to a joint control. Whether the intent is to disable or merely to distract, a sincere atemi should force uke to respond in a manner that makes the application of the technique more effective.

Kiai (audible exhalations of energy) were also used and taught by Ueshiba and are used in most traditional aikido schools.

Attacks

When Ueshiba first began teaching the public, most of his students were proficient in another martial art and it was not necessary to teach them attack techniques. For this reason, contemporary aikido dojos do not focus on attacks, though students will learn the various attacks from which an aikido technique can be practiced. Good attacks are needed in order to study correct and effective application of aikido technique. It is important that the attacks be âhonest;â attacks with full intention or a strong grab or immobilizing hold. The speed of an attack may vary depending on the experience and ranking of the nage.

Aikido attacks used in normal training include various stylized strikes and grabs such as shomenuchi (a vertical strike to the head), yokomenuchi (a lateral strike to the side of the head and/or neck), munetsuki (a punch to the stomach), ryotedori (a two handed grab) or katadori (a shoulder grab). Many of the -uchi strikes resemble blows from a sword or other weapon.

Randori

One of the central martial principles of aikido is to be able to handle multiple attackers fluidly. Randori, or jiyuwaza (freestyle) practice against multiple opponents, is a key part of the curriculum in most aikido schools and is required for the higher level belts. Randori is mostly intended to develop a person's ability to perform without thought, and with their mind and body coordinated. The continued practice of having one opponent after another coming at you without rest develops your awareness and the connection between mind and body.

Shodokan Aikido randori differs in that it is not done with multiple attackers, but between two people with both participants able to attack, defend and resist at will. In this case, as in judo, the roles of uke and nage do not exist.

Another tenet of aikido is that the aikidoka should gain control of his opponent as quickly as possible, while causing the least amount of damage possible to either party.

Weapons

Weapons training in aikido usually consists of jo (a staff approximately fifty inches long), bokken (wooden sword), and wooden tanto (knife). Both weapons-taking and weapons-retention are sometimes taught, to integrate the armed and unarmed aspects of aikido.

Many schools use versions of Morihiro Saito's weapons system: aiki-jo and aiki-ken.

Clothing

The aikidogi used in aikido is similar to the keikogi used in most other modern budo (martial) arts; simple trousers and a wraparound jacket, usually white.

To the keikogi, some systems add a traditional hakama. The hakama is usually black or dark blue, and in most dojo is reserved for practitioners with dan (black belt) ranks.

Although some systems use many belt colors similar to the system in judo, the most common version is that dan ranks wear black belt, and kyu ranks white, sometimes with an additional brown belt for the highest kyu ranks.

"Ki"

The Japanese character for ki (Qi in Chinese) is a symbolic representation of a lid covering a pot full of rice. The steam being contained within is ki. This same word is applied to the ability to harness one's own 'breath power,' 'power,' or 'energy'. Teachers describe ki as coming from the hara, situated in the lower abdomen, about two inches below and behind the navel. In training these teachers emphasize that one should remain centered. Very high ranking teachers are said to sometimes reach a level of ki that enables them to execute techniques without touching their opponent's body.

The spiritual interpretation of ki depends very much on what school of aikido one studies; some emphasize it more than others. Ki Society dojos, for example, spend much more time on ki-related training activities than do, for example, Yoshinkan dojos. The importance of ki in aikido cannot be denied, but the definition of ki is debated by many within the discipline. Morihei Ueshiba himself appears to have changed his views over time. Yoshinkan Aikido, which largely follows Ueshibaâs teachings from before the war, is considerably more martial in nature, reflecting a younger, more violent and less spiritual nature. Within this school, ki could be considered to have its original Chinese meaning of "breath," and aikido as coordination of movement with breath to maximize power. As Ueshiba evolved and his views changed, his teachings took on a much more spiritual element, and many of his later students (almost all now high ranking sensei within the Aikikai) teach about ki from this perspective.

Body

Aikido training is for all-around physical fitness, flexibility, and relaxation. The human body in general can exert power in two ways: contractive and expansive. Many fitness activities, for example weight-lifting, emphasize the contractive, in which specific muscles or muscle groups are isolated and worked to improve tone, mass, and power. The disadvantage is that whole body movement and coordination are rarely emphasized, and that this type of training tends to increase tension, decrease flexibility, and stress the joints. The second type of power, expansive, is emphasized in activities such as dance or gymnastics, where the body must learn to move in a coordinated manner and with relaxation. Aikido emphasizes this type of training. While both types of power are important, a person who masters expansive power can, in martial arts, often overcome a person who is much bigger or stronger, because movement involves the whole body and starts from the center, where the body is most powerful.

Aikido develops the body in a unique manner. Aerobic fitness is obtained through vigorous training, and flexibility of the joints and connective tissues is developed through various stretching exercises and through practicing the techniques themselves. Relaxation is learned automatically, since the techniques cannot be performed without it. A balanced use of contractive and expansive power is mastered, enabling even a small person to pit the energy of his entire body against an opponent.

Mind

Aikido training does not consider the body and mind as independent entities. The condition of one affects the other. The physical relaxation learned in aikido also becomes a mental relaxation; the mental confidence that develops is manifested in a more confident style. The psychological or spiritual insight learned during training must become reflected in the body, or it will vanish under pressure, when more basic, ingrained patterns and reflexes take over. Aikido training requires the student to squarely face conflict, not to run away from it. Through this experience, an Aikido student learns to face other areas of life with confidence rather than avoidance and fear.

Ranking

The vast majority of aikido styles use the kyu (dan) ranking system common to gendai budo; however the actual requirements for each belt level differs between styles, so they are not necessarily comparable or interchangeable. Some organizations of aikido use colored belts for kyu levels, and some do not.

Styles

The major styles of aikido each have their own Hombu Dojo in Japan, have an international breadth and were founded by former students of Morihei Ueshiba. Although there has been an explosion of "independent styles" generally only six are considered major.

- Aikikai is the largest aikido organization, and is led by the family of the Ueshiba. Numerous sub-organizations and teachers affiliate themselves with this umbrella organization, which therefore encompasses a wide variety of aikido styles, training methods and technical differences. The sub-organizations are often centered around prominent Shihan and are usually organized at the national level.

- Yoshinkan, founded by Gozo Shioda, has a reputation for being the most rigidly precise school. Students of Yoshinkan aikido practice basic movements as solo kata, and this style has been popular among the Japanese police. The international organization associated with the Yoshinkan style of aikido is known as the Yoshinkai, and has active branches in many parts of the world.

- Yoseikan was founded by Minoru Mochizuki, an early student of Ueshiba and also of Jigoro Kano at the Kodokan. This style includes elements of aiki-budo together with aspects of karate, judo and other arts. It is now carried on by his son, Hiroo Mochizuki, the creator of Yoseikan Budo.

- Shodokan Aikido (often called Tomiki Aikido, after its founder) uses sparring and rule based competition in training, unlike most other schools of aikido. Kenji Tomiki, an early student of Uebashi and also of judo's Jigoro Kano, believed that introducing an element of competition would serve to sharpen and focus the practice since it was no longer tested in real combat. This view caused a split with Ueshibaâs family, who firmly believed that there was no place for competition in aikido training.

- The Ki Society, founded by former chief instructor of the Aikikai Hombu dojo, Koichi Tohei, emphasizes very soft flowing techniques and has a special program for the development of ki. It also has a special system of ki-ranks alongside the traditional kyu and dan system. This style is also called Shin Shin Toitsu Aikido (or Ki-Aikido).

- Iwama style emphasizes the relation between weapon techniques and barehand techniques (riai). Since the death of its founder Morihiro Saito, the Iwama style has been practiced by clubs within the Aikikai and an independent organization headed by Hitohiro Saito. Morihiro Saito was a long time uchideshi of Ueshiba, from 1946 until his death. Morihiro Saito said he was trying to preserve and teach the art exactly as the founder of aikido taught it to him. Technically, Iwama-ryu resembles the aikido Ueshiba taught in the early 1950s at the Iwama dojo and has a large technical repertoire.

Aikidoka

It is sometimes said that in Japan the term aikidoka (åæ°é家) mainly refers to a professional, while in the West, anyone who practices aikido may call themselves an aikidoka. The term aikidoist is also used as a more general term, especially by those who prefer to maintain the more restricted, Japanese, meaning of the term aikidoka.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Crum, Thomas F. Journey to Center: Lessons in Unifying Body, Mind, and Spirit. Fireside, 1997. ISBN 978-0684839226

- Ueshiba, Kisshomaru. The Art Of Aikido: Principles And Essential Techniques. Japan: Kodansha International (JPN), 2004. ISBN 978-4770029454

- Ueshiba, Kisshomaru and Moriteru Ueshiba. Best Aikido: The Fundamentals, translated by John Stevens, (Illustrated Japanese Classics) Japan: Kodansha International (JPN), 2002. ISBN 978-4770027627

- Ueshiba, Morihei and John Stevens. The Essence of Aikido: Spiritual Teachings of Morihei Ueshiba. Kodansha International (JPN), 1999. ISBN 978-4770023575

- Westbrook, Adele and Oscar Ratti. Aikido and the Dynamic Sphere: An Illustrated Introduction. Tuttle Publishing, 2001. ISBN 978-0804832847

External links

All links retrieved June 16, 2023.

- Aikikai Foundation

- Aikidosphere

- Aikido.com

- AikiWeb Aikido Information is a comprehensive site on aikido, with essays, forums, gallery, reviews, columns, wiki and other information.

- Aikido Journal Website An extensive source of aikido historical information.

- International Aikido Federation

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.