African wild ass

| African wild ass | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Somali Wild Ass (Equus africanus somalicus)

| ||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Equus africanus Linnaeus, 1758 | ||||||||||||||||

|

E. a. africanus |

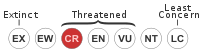

African wild ass is the common name for a wild member of the horse family, Equus africanus (sometimes E. asinus), characterized by long legs, long ears, erect mane, and a stripe down the back and some members with leg stripes. This odd-toed ungulate is believed to be the ancestor of the domestic donkey, which is usually placed within the same species. African wild asses live in the deserts and other arid areas of northeastern Africa, in Eritrea, Ethiopia, and Somalia; it formerly had a wider range north and west into Sudan, Egypt, and Libya. Classified as Critically Endangered, about 570 individuals exist in the wild.

African wild asses have had a long association with people, being used for food and traditional medicine. They also have been captured for domestication, and it is believed domesticated members were used for pulling wagons in ancient Sumer about 2600 B.C.E. and appear on the Standard of UR, a Sumerian artifact, dating to around 2600 to 2400 B.C.E. Donkeys may have been first domesticated from the African wild ass as early as 4000 B.C.E.

Overview and description

The African wild ass is a member of the Equidae, a family of odd-toed ungulate mammals of horses and horse-like animals. There are three basic groups recognized in Equidae‚ÄĒhorses, asses, and zebras‚ÄĒalthough all extant equids are in the same genus of Equus. The African wild ass is one of three or four extant species of asses, which are placed together in the subgenus Asinus. The other species known as asses are the donkey or ass (E. asinus), onager (E. hemionus), and kiang (E. kiang). The African wild ass typically is classified as E. africanus, but the species name is sometimes designated as asinus. The domesticated donkey often is placed as a subspecies of its presumed wild ancestor, the African wild ass. Some taxonomic schemes list the donkey as its own species, E. asinus, and the African wild ass as E. africanus.

The African wild ass is a medium-sized ungulate, about 2 meters (6.5 feet) in body length and 1.25 to 1.45 meters (4.1250-4.785 feet) tall at the shoulders, with a tail 30 to 50 centimeters (12-20 inches) long. It weighs between 230 and 280 kilograms (507-615 pounds). The legs are long. The ears are large with black margins. The tail terminates with a black brush. The hooves are slender and approximately the diameter of the legs.

The short, smooth, shiny coat is a light gray to fawn or tan color, fading to white on the undersides and legs. There is a slender, dark dorsal stripe in all subspecies, while in the Nubian wild ass subspecies (E. a. africanus), as well as the domestic donkey, there is a stripe across the shoulder. The legs of the Somali wild ass subspecies (E. a. somalicus) are horizontally striped with black, resembling those of a zebra. The stripe patterns on the legs make it possible to distinguish individuals (Moehlman 2004). The Somali subspecies may occasionally also have a shoulder stripe; the Nubian subspecies does not have leg stripes (Grzimek et al. 2004). On the nape of the neck there is a stiff, upright mane, the hairs of which are tipped with black.

Distribution and habitat

The historic range of the African wild ass has been greatly reduced‚ÄĒby more than ninety percent‚ÄĒin just the last couple of decades. Today, it is found in low density in Eritrea and Ethiopia, with a small population in Somalia (Grzimek et al. 2004).

African wild asses live in extreme desert conditions where there is less than 200 millimeters (7.8 inches) of annual rainfall. They are well suited to life in a desert or semi-desert environment. They have tough digestive systems, which can break down desert vegetation and extract moisture from food efficiently. They can also go without water for a fairly long time. Their large ears give them an excellent sense of hearing and help in cooling.

Behavior

Because of the sparse vegetation in their environment wild asses live somewhat separated from each other (except for mothers and young), unlike the tightly grouped herds of wild horses. They tend to live in temporary groups of less than five individuals, with the only stable groups that of a female and her offspring (Grzimek et al. 2004). Some temporary herds can be larger, even up to fifty animals, although these last no more than a few months (ARKive). They have very loud voices, which can be heard for over 3 kilometers (2 miles), which helps them to keep in contact with other asses over the wide spaces of the desert.

Mature males defend large territories around 23 square kilometers in size, marking them with dung heaps‚ÄĒan essential marker in the flat, monotonous terrain. Due to the size of these ranges, the dominant male cannot exclude other males. Rather, intruders are tolerated, recognized, treated as subordinates, and kept as far away as possible from any of the resident females. In the presence of estrous females, the males bray loudly.

The African wild ass is primarily active in the cooler hours between late afternoon and early morning, seeking shade and shelter among the rocky hills during the day. Swift and sure-footed in their rough, rocky habitat, the African wild ass has been clocked at 50 kilometers per hour (30 miles per hour).

Although wild asses can run swiftly, almost as fast as a horse, unlike most hoofed mammals, their tendency is to not flee right away from a potentially dangerous situation, but to investigate first before deciding what to do. When they need to, they can defend themselves with kicks from both their front and hind legs.

Equids were used in ancient Sumer to pull wagons around 2600 B.C.E., and then chariots as reflected on the Standard of Ur artifact around the same time period. These have been suggested to represent onagers, but are now thought to have been domestic asses (Clutton-Brock 1992).

Diet

As equids, the African wild ass is a herbivore, that feeds primarily on tough, fibrous food. In particular, the diet of the African wild ass consists of grasses, bark, and leaves. Despite being primarily adapted for living in an arid climate, African wild asses are dependent on water, and when not receiving the needed moisture from vegetation, they must drink at least once every three days. However, they can survive on a surprisingly small amount of liquid, and have been reported to drink salty or brackish water. As with other equids, cellulose is broken down in the "hindgut" or cecum, a part of the colon, a process known as hindgut fermentation.

Conservation status

Though the species itself is under no threat of extinction, due to abundant domestic stock (donkey and burros), the two extant wild subspecies are both listed as Critically Endangered. There are now only a few hundred individuals left in the wild. A noted above, there has been a ninety percent reduction in their range in the last 20 years (Grzimek et al. 2004).

Among pressures put on populations of African wild asses is the fact that they have been captured for domestication for centuries and there also have been interbreeding between wild and domestic animals. Other major threats include being hunted for food and for traditional medicine in both Ethiopia and Somalia, as well as competition with domestic livestock for water and forage. Agricultural development also has resulted in restricted access to water (ARKive; Grzimek et al. 2004).

The African wild ass is legally protected in its range. However, these protective measures are difficult to force and interbreeding and habitat loss remain concerns. The Yotvata Hai-Bar Nature Reserve in Israel, to the north of Eilat, was established in 1968 and offers protection for a population of the Somali wild ass. If the species if properly protected, it is possible it can recover from its current low, as evidenced by the resiliency of populations of horses and asses (ARKive).

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ARKive. n.d. African wild ass (Equus africanus). ARKive. Retrieved Janury 6, 2009.

- Clutton-Brock, J. 1992. Horse Power: A History of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674406469.

- Grzimek, B., D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade, Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale, 2004. ISBN 0307394913.

- Moehlman, P. D. 2004. Equidae. In B. Grzimek, D. G. Kleiman, V. Geist, and M. C. McDade, Grzimek's Animal Life Encyclopedia. Detroit: Thomson-Gale, 2004. ISBN 0307394913.

- Moehlman, P. D., H. Yohannes, R. Teclai, and F. Kebede. 2008. Equus africanus. In IUCN, 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved January 6, 2009.

- Savage, R. J. G., and M. R. Long. 1986. Mammal Evolution: An Illustrated Guide. New York: Facts on File. ISBN 081601194X.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.