Difference between revisions of "Mary I of Scotland" - New World Encyclopedia

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) |

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 23: | Line 23: | ||

'''Mary I of Scotland ''' ('''Mary Stuart''', popularly known as '''Mary, Queen of Scots'''); (December 8, 1542 – February 8, 1587) was the Queen of Scots (the monarch of the Kingdom of Scotland) from December 14, 1542 to July 24, 1567. She also sat as Queen Consort of [[France]] from July 10, 1559 to December 5, 1560. Because of her tragic life, she is one of the best-known Scottish monarchs. | '''Mary I of Scotland ''' ('''Mary Stuart''', popularly known as '''Mary, Queen of Scots'''); (December 8, 1542 – February 8, 1587) was the Queen of Scots (the monarch of the Kingdom of Scotland) from December 14, 1542 to July 24, 1567. She also sat as Queen Consort of [[France]] from July 10, 1559 to December 5, 1560. Because of her tragic life, she is one of the best-known Scottish monarchs. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==Early Life== | ==Early Life== | ||

| Line 85: | Line 81: | ||

Following the birth of their son, James, in 1566, a plot was hatched to remove Darnley, who was already ill. He was recuperating in a house in Edinburgh where Mary visited him frequently. In February 1567, an explosion occurred in the house, and Darnley was found dead in the garden, apparently of strangulation. This event, which should have been Mary's salvation, only harmed her reputation. James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, an adventurer who would become her third husband, was generally believed to be guilty of the assassination, and was brought before a mock trial but acquitted. Mary attempted to regain support among her Lords while Bothwell got some of them to sign the Ainslie Tavern Bond, in which they agreed to support his claims to marry Mary. | Following the birth of their son, James, in 1566, a plot was hatched to remove Darnley, who was already ill. He was recuperating in a house in Edinburgh where Mary visited him frequently. In February 1567, an explosion occurred in the house, and Darnley was found dead in the garden, apparently of strangulation. This event, which should have been Mary's salvation, only harmed her reputation. James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, an adventurer who would become her third husband, was generally believed to be guilty of the assassination, and was brought before a mock trial but acquitted. Mary attempted to regain support among her Lords while Bothwell got some of them to sign the Ainslie Tavern Bond, in which they agreed to support his claims to marry Mary. | ||

| − | == Abdication | + | == Abdication and imprisonment == |

| − | On April 24 Mary visited her son at Stirling for the last time. On her way back to Edinburgh Mary was abducted, willingly or not, by Bothwell and his men and taken to Dunbar Castle. On May 6 | + | On April 24 Mary visited her son at Stirling for the last time. On her way back to Edinburgh Mary was abducted, willingly or not, by Bothwell and his men and taken to Dunbar Castle. On May 6 they returned to Edinburgh and on May 15, at Holyrood Palace, Mary and Bothwell were married according to [[Protestant]] rites. |

The Scottish nobility turned against Mary and Bothwell and raised an army against them. The Lords took Mary to Edinburgh and imprisoned her in Loch Leven Castle. On July 24, 1567, she was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favor of her one-year-old son James. | The Scottish nobility turned against Mary and Bothwell and raised an army against them. The Lords took Mary to Edinburgh and imprisoned her in Loch Leven Castle. On July 24, 1567, she was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favor of her one-year-old son James. | ||

| Line 95: | Line 91: | ||

On May 2, 1568, Mary escaped from Loch Leven and once again managed to raise a small army. After her army's defeat at the Battle of Langside on May 13, she fled to England. When Mary entered England on May 19, she was imprisoned by Elizabeth's officers at Carlisle. | On May 2, 1568, Mary escaped from Loch Leven and once again managed to raise a small army. After her army's defeat at the Battle of Langside on May 13, she fled to England. When Mary entered England on May 19, she was imprisoned by Elizabeth's officers at Carlisle. | ||

| − | + | Elizabeth ordered an inquiry into Darnley's murder which was held in York. Mary refused to acknowledge the power of any court to try her since she was an anointed Queen, and the man ultimately in charge of the prosecution, James Stewart, Earl of Moray, was ruling Scotland in Mary's absence. His chief motive was to keep Mary out of Scotland and her supporters under control. Mary was not permitted to see them or to speak in her own defense at the tribunal. She refused to offer a written defense unless Elizabeth would guarantee a verdict of not guilty, which Elizabeth would not do. | |

| − | |||

| − | Mary refused to acknowledge the power of any court to try her since she was an anointed Queen, and the man ultimately in charge of the prosecution, | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | The inquiry hinged on the "The Casket Letters"—eight letters purportedly from Mary to Bothwell, reported by [[James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton]] to have been found in Edinburgh in a silver box engraved with an F (supposedly for Francis II), along with a number of other documents, including the Mary/Bothwell marriage certificate. The authenticity of the Casket Letters has been the source of much controversy among historians. Mary argued that her handwriting was not difficult to imitate, and it has frequently been suggested either that the letters are complete forgeries, that incriminating passages were inserted before the inquiry, or that the letters were written to Bothwell by some other person. Comparisons of writing style have often concluded that they were not Mary's work. | |

| − | + | Elizabeth considered Mary's designs on the English throne to be a serious threat, and so eighteen years of confinement followed. Bothwell was imprisoned in [[Denmark]], became insane, and died in 1578, still in prison. | |

| − | + | In 1570, Elizabeth was persuaded by representatives of [[Charles IX of France]] to promise to help Mary regain her throne. As a condition, she demanded the ratification of the Treaty of Edinburgh, something Mary would still not agree. Nevertheless, William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, continued negotiations with Mary on Elizabeth's behalf. | |

| − | Mary | + | The Ridolfi Plot, which attempted to unite Mary and the Duke of Norfolk in marriage, caused Elizabeth to reconsider. With the queen's encouragement, Parliament introduced a bill in 1572 barring Mary from the throne. Elizabeth unexpectedly refused to give it the royal assent. The furthest she ever went was in 1584, when she introduced a document (the "Bond of Association") aimed at preventing any would-be successor from profiting from her murder. It was not legally binding, but was signed by thousands, including Mary herself. |

| − | + | Mary eventually became a liability that Elizabeth could no longer tolerate. Elizabeth did ask Mary's final custodian, Amias Paulet, if he would contrive some accident to remove Mary. He refused on the grounds that he would not allow such "a stain on his posterity." Mary was implicated in several plots to assassinate Elizabeth and put herself on the throne, possibly with French or Spanish help. The major plot for the political takeover was the Babington Plot, but some of Mary's supporters believed it and other plots to be either fictitious or undertaken without Mary's knowledge. | |

| − | Mary | + | [[Image:Mary Queen of Scots.jpg|thumb|left|One of The London Dungeon's exhibitions is about Mary, Queen of Scots]] |

| − | + | ==Trial and execution== | |

| + | Mary was put on trial for treason by a court of about 40 noblemen, including Catholics, after being implicated in the Babington Plot and after having allegedly sanctioned the assassination of Elizabeth. Mary denied the accusation and was spirited in her defense. She drew attention to the fact that she was denied the opportunity of reviewing the evidence or her papers that had been removed from her, that she had been denied access to legal counsel and that she had never been an English subject and thus could not be convicted of treason. The extent to which the plot was created by Sir Francis Walsingham and the English Secret Services will always remain open to conjecture. | ||

| − | + | In a trial presided over by England's Chief of Justice, Sir John Popham, Mary was ultimately convicted of treason, and was beheaded at Fotheringay Castle, Northamptonshire on February 8, 1587. She had spent the last hours of her life in prayer and also writing letters and her will. She expressed a request that her servants should be released. She also requested that she should be buried in France. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

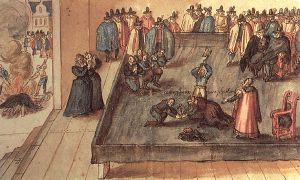

[[Image:Maria_Stuart_Execution.jpg|thumb|right|The execution of Mary Stuart drawn by a Dutch artist]] | [[Image:Maria_Stuart_Execution.jpg|thumb|right|The execution of Mary Stuart drawn by a Dutch artist]] | ||

| − | |||

In response to Mary's death, the [[Spanish Armada]] sailed to England to depose Elizabeth, but it lost a considerable number of ships in the [[Spanish_Armada#Battle_of_Gravelines|Battle of Gravelines]] and ultimately retreated without touching English soil. | In response to Mary's death, the [[Spanish Armada]] sailed to England to depose Elizabeth, but it lost a considerable number of ships in the [[Spanish_Armada#Battle_of_Gravelines|Battle of Gravelines]] and ultimately retreated without touching English soil. | ||

Mary's body was [[embalm]]ed and left unburied at her place of execution for a year after her death. Her remains were placed in a secure lead coffin (thought to be further signs of fear of relic hunting). She was initially buried at [[Peterborough Cathedral]] in 1588, but her body was exhumed in 1612 when her son, King [[James I of England]], ordered she be reinterred in [[Westminster Abbey]]. It remains there, along with at least 40 other descendants, in a chapel on the other side of the Abbey from the grave of her cousin Elizabeth. In the 1800s her tomb and that of Elizabeth I were opened to try to ascertain where James I was buried; he was ultimately found buried with Henry VII. | Mary's body was [[embalm]]ed and left unburied at her place of execution for a year after her death. Her remains were placed in a secure lead coffin (thought to be further signs of fear of relic hunting). She was initially buried at [[Peterborough Cathedral]] in 1588, but her body was exhumed in 1612 when her son, King [[James I of England]], ordered she be reinterred in [[Westminster Abbey]]. It remains there, along with at least 40 other descendants, in a chapel on the other side of the Abbey from the grave of her cousin Elizabeth. In the 1800s her tomb and that of Elizabeth I were opened to try to ascertain where James I was buried; he was ultimately found buried with Henry VII. | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

Revision as of 18:55, 18 March 2007

| Mary I of Scotland | ||

|---|---|---|

| Queen of Scots | ||

| ||

| Reign | December 14, 1542 – July 24, 1567 | |

| Coronation | September 9, 1543 | |

| Born | December 8, 1542 1:12pm LMT | |

| Linlithgow Palace, West Lothian | ||

| Died | February 8, 1587 | |

| Fotheringhay Castle, Northamptonshire | ||

| Buried | Peterborough Cathedral Westminster Abbey | |

| Predecessor | James V | |

| Successor | James VI/James I of England | |

| Consort | François II of France Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell | |

| Royal House | Stewart | |

| Father | James V | |

| Mother | Marie of Guise | |

Mary I of Scotland (Mary Stuart, popularly known as Mary, Queen of Scots); (December 8, 1542 – February 8, 1587) was the Queen of Scots (the monarch of the Kingdom of Scotland) from December 14, 1542 to July 24, 1567. She also sat as Queen Consort of France from July 10, 1559 to December 5, 1560. Because of her tragic life, she is one of the best-known Scottish monarchs.

Early Life

Princess Mary Stuart was born at Linlithgow Palace, Linlithgow, West Lothian, Scotland to King James V of Scotland and his French wife, Marie de Guise. In Falkland Palace, Fife, her father heard of the birth and prophesied, "The devil go with it! It came with a lass, it will pass with a lass!" James truly believed that Mary's birth marked the end of the Stuarts' reign over Scotland. Instead, through Mary's son, it was the beginning of their reign over both the Kingdom of Scotland and the Kingdom of England.

The six-day-old Mary became Queen of Scotland when her father died at the age of thirty. James Hamilton, 2nd Earl of Arran was the next in line for the throne after Mary; he acted as regent for Mary until 1554, when he was succeeded by the Queen's mother, who continued as regent until her death in 1560.

In July 1543, when Mary was six months old, the Treaties of Greenwich promised Mary to be married to Edward, son of King Henry VIII of England in 1552, and for their heirs to inherit the Kingdoms of Scotland and England. Mary's mother was strongly opposed to the proposition, and she hid with Mary two months later in Stirling Castle, where preparations were made for Mary's coronation.

When Mary was only nine months old she was crowned Queen of Scotland in the Chapel Royal at Stirling Castle on September 9, 1543. Because the Queen was an infant and the ceremony unique, Mary's coronation was the talk of Europe. She was magnificently dressed for the occasion in an elaborate satin jeweled gown beneath a red velvet mantle, trimmed with ermine. Unable to yet walk she was carried by Lord Livingston in solemn procession to the Chapel Royal. Inside, Lord Livingston brought Mary forward to the altar, put her gently in the throne set up there, and stood by holding her to keep her from rolling off.

Quickly, Cardinal David Beaton put the Coronation Oath to her, which Lord Livingston answered for her. The Cardinal immediately unfastened Mary's heavy robes and began anointing her with the holy oil. The Sceptre was brought forth and placed it in Mary's hand, and she grasped the heavy shaft. Then the Sword of State was presented by the Earl of Argyll, and the Cardinal performed the ceremony of girding the three-foot sword to the tiny body.

The Earl of Arran delivered the royal Crown to Cardinal Beaton who placed it gently onto the child's head. The Cardinal steadied the crown as the kingdom came up and knelt before the tiny queen placing their hands on her crown and swearing allegiance to her.

The "rough wooing"

The Treaties of Greenwich fell apart soon after Mary's coronation. The betrothal did not sit well with the Scots, especially since King Henry VIII suspiciously tried to change the agreement so that he could possess Mary years before the marriage was to take place. He also wanted them to break their traditional alliance with France. Fearing an uprising among the people, the Scottish Parliament broke off the treaty and the engagement at the end of the year.

Henry VIII then began his "rough wooing" designed to impose the marriage to his son on Mary. This consisted of a series of raids on Scottish territory and other military actions. It lasted until June 1551, costing over half a million pounds and many lives. In May of 1544, the English Earl of Hertford (later created Duke of Somerset by Edward VI) arrived in the Firth of Forth hoping to capture the city of Edinburgh and kidnap Mary, but Marie de Guise hid her in the secret chambers of Stirling Castle.

On September 10, 1547, known as "Black Saturday", the Scots suffered a bitter defeat at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh. Marie de Guise, fearful for her daughter, sent her temporarily to Inchmahome Priory, and turned to the French ambassador Monsieur D'Oysel.

The French, remaining true to the Auld Alliance, came to the aid of the Scots. The new French King, Henri II, was now proposing to unite France and Scotland by marrying the little Queen to his newborn son, the Dauphin François. This seemed to Marie to be the only sensible solution to her troubles. In February 1548, hearing that the English were on their way back, Marie moved Mary to Dumbarton Castle. The English left a trail of devastation behind once more and seized the strategically located town of Haddington. By June, the much awaited French help had arrived. On July 7, the French Marriage Treaty was signed at a nunnery near Haddington.

Childhood in France

With her marriage agreement in place, five-year-old Mary was sent to France in 1548 to spend the next ten years at the French court. Henri II had offered to guard her and raise her. On August 7, 1548, the French fleet sent by Henri II sailed back to France from Dumbarton carrying the five-year-old Queen of Scotland on board. She was accompanied by her own little court consisting of two lords, two half brothers, and the "four Marys", four little girls her own age, all named Mary, and the daughters of the noblest families in Scotland: Beaton, Seton, Fleming, and Livingston.

Vivacious, pretty, and clever, Mary had a promising childhood. While in the French court, she was a favorite. She received the best available education, and at the end of her studies, she had mastered French, Latin, Greek, Spanish and Italian in addition to her native Scots. She also learned how to play two instruments and learned prose, horsemanship, falconry, and needlework.

On April 24, 1558 she married the dauphin François at Notre Dame de Paris. When Henri II died on July 10, 1559, Mary became Queen Consort of France; her husband became François II of France.

Claim to the English throne

Under the ordinary laws of succession, Mary was also next in line to the English throne after her cousin, Queen Elizabeth I, who was childless. In the eyes of many Catholics Elizabeth was illegitimate, making Mary the true heir.

The anti-Catholic Act of Settlement was not passed until 1701, but the last will and testament of Henry VIII had excluded the Stuarts from succeeding to the English throne. Mary's troubles were still further increased by the Huguenot rising in France, called le tumulte d'Amboise (March 6–17, 1560), making it impossible for the French to succor Mary's side in Scotland. The question of the succession was therefore a real one.

François died on December 5, 1560. Mary's mother-in-law, Catherine de Medici, became regent for the late king's brother Charles IX, who inherited the French throne. Under the terms of the Treaty of Edinburgh, signed by Mary's representatives on July 6, 1560 following the death of Marie of Guise, France undertook to withdraw troops from Scotland and recognize Elizabeth's right to rule England. The eighteen-year-old Mary, still in France, refused to ratify the treaty.

Religious divide

Mary returned to Scotland soon after her husband's death and arrived in Leith on August 19, 1561. Despite her talents, Mary's upbringing had not given her the judgment to cope with the dangerous and complex political situation in the Scotland of the time.

Mary, being a devout Roman Catholic, was regarded with suspicion by many of her subjects as well as by Elizabeth, who was her father's cousin and the monarch of the neighboring Protestant country. Scotland was torn between Catholic and Protestant factions, and Mary's illegitimate half-brother, James Stewart, 1st Earl of Moray, was a leader of the Protestant faction. The Protestant reformer John Knox also preached against Mary, condemning her for hearing Mass, dancing, dressing too elaborately, and many other things, real and imagined.

To the disappointment of the Catholic party, however, Mary did not hasten to take up the Catholic cause. She tolerated the newly-established Protestant ascendancy, and kept James Stewart as her chief advisor. In this, she may have had to acknowledge her lack of effective military power in the face of the Protestant Lords. She joined with James in the destruction of Scotland's leading Catholic magnate, Lord Huntly, in 1562.

Mary was also having second thoughts about the wisdom of having crossed Elizabeth, and she attempted to make up the breach by inviting Elizabeth to visit Scotland. Elizabeth refused, and the bad blood remained between them.

Marriage to Darnley

At Holyrood Palace on July 29, 1565, Mary married Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley, a descendant of King Henry VII of England and Mary's first cousin. The union infuriated Elizabeth, who felt she should have been asked permission for the marriage to even take place, as Darnley was an English subject. Elizabeth also felt threatened by the marriage, because Mary's and Darnley's Scottish and English royal blood would produce children with extremely strong claims to both Mary's and Elizabeth's thrones.

Following the birth of their son, James, in 1566, a plot was hatched to remove Darnley, who was already ill. He was recuperating in a house in Edinburgh where Mary visited him frequently. In February 1567, an explosion occurred in the house, and Darnley was found dead in the garden, apparently of strangulation. This event, which should have been Mary's salvation, only harmed her reputation. James Hepburn, 4th Earl of Bothwell, an adventurer who would become her third husband, was generally believed to be guilty of the assassination, and was brought before a mock trial but acquitted. Mary attempted to regain support among her Lords while Bothwell got some of them to sign the Ainslie Tavern Bond, in which they agreed to support his claims to marry Mary.

Abdication and imprisonment

On April 24 Mary visited her son at Stirling for the last time. On her way back to Edinburgh Mary was abducted, willingly or not, by Bothwell and his men and taken to Dunbar Castle. On May 6 they returned to Edinburgh and on May 15, at Holyrood Palace, Mary and Bothwell were married according to Protestant rites.

The Scottish nobility turned against Mary and Bothwell and raised an army against them. The Lords took Mary to Edinburgh and imprisoned her in Loch Leven Castle. On July 24, 1567, she was forced to abdicate the Scottish throne in favor of her one-year-old son James.

On May 2, 1568, Mary escaped from Loch Leven and once again managed to raise a small army. After her army's defeat at the Battle of Langside on May 13, she fled to England. When Mary entered England on May 19, she was imprisoned by Elizabeth's officers at Carlisle.

Elizabeth ordered an inquiry into Darnley's murder which was held in York. Mary refused to acknowledge the power of any court to try her since she was an anointed Queen, and the man ultimately in charge of the prosecution, James Stewart, Earl of Moray, was ruling Scotland in Mary's absence. His chief motive was to keep Mary out of Scotland and her supporters under control. Mary was not permitted to see them or to speak in her own defense at the tribunal. She refused to offer a written defense unless Elizabeth would guarantee a verdict of not guilty, which Elizabeth would not do.

The inquiry hinged on the "The Casket Letters"—eight letters purportedly from Mary to Bothwell, reported by James Douglas, 4th Earl of Morton to have been found in Edinburgh in a silver box engraved with an F (supposedly for Francis II), along with a number of other documents, including the Mary/Bothwell marriage certificate. The authenticity of the Casket Letters has been the source of much controversy among historians. Mary argued that her handwriting was not difficult to imitate, and it has frequently been suggested either that the letters are complete forgeries, that incriminating passages were inserted before the inquiry, or that the letters were written to Bothwell by some other person. Comparisons of writing style have often concluded that they were not Mary's work.

Elizabeth considered Mary's designs on the English throne to be a serious threat, and so eighteen years of confinement followed. Bothwell was imprisoned in Denmark, became insane, and died in 1578, still in prison.

In 1570, Elizabeth was persuaded by representatives of Charles IX of France to promise to help Mary regain her throne. As a condition, she demanded the ratification of the Treaty of Edinburgh, something Mary would still not agree. Nevertheless, William Cecil, 1st Baron Burghley, continued negotiations with Mary on Elizabeth's behalf.

The Ridolfi Plot, which attempted to unite Mary and the Duke of Norfolk in marriage, caused Elizabeth to reconsider. With the queen's encouragement, Parliament introduced a bill in 1572 barring Mary from the throne. Elizabeth unexpectedly refused to give it the royal assent. The furthest she ever went was in 1584, when she introduced a document (the "Bond of Association") aimed at preventing any would-be successor from profiting from her murder. It was not legally binding, but was signed by thousands, including Mary herself.

Mary eventually became a liability that Elizabeth could no longer tolerate. Elizabeth did ask Mary's final custodian, Amias Paulet, if he would contrive some accident to remove Mary. He refused on the grounds that he would not allow such "a stain on his posterity." Mary was implicated in several plots to assassinate Elizabeth and put herself on the throne, possibly with French or Spanish help. The major plot for the political takeover was the Babington Plot, but some of Mary's supporters believed it and other plots to be either fictitious or undertaken without Mary's knowledge.

Trial and execution

Mary was put on trial for treason by a court of about 40 noblemen, including Catholics, after being implicated in the Babington Plot and after having allegedly sanctioned the assassination of Elizabeth. Mary denied the accusation and was spirited in her defense. She drew attention to the fact that she was denied the opportunity of reviewing the evidence or her papers that had been removed from her, that she had been denied access to legal counsel and that she had never been an English subject and thus could not be convicted of treason. The extent to which the plot was created by Sir Francis Walsingham and the English Secret Services will always remain open to conjecture.

In a trial presided over by England's Chief of Justice, Sir John Popham, Mary was ultimately convicted of treason, and was beheaded at Fotheringay Castle, Northamptonshire on February 8, 1587. She had spent the last hours of her life in prayer and also writing letters and her will. She expressed a request that her servants should be released. She also requested that she should be buried in France.

In response to Mary's death, the Spanish Armada sailed to England to depose Elizabeth, but it lost a considerable number of ships in the Battle of Gravelines and ultimately retreated without touching English soil.

Mary's body was embalmed and left unburied at her place of execution for a year after her death. Her remains were placed in a secure lead coffin (thought to be further signs of fear of relic hunting). She was initially buried at Peterborough Cathedral in 1588, but her body was exhumed in 1612 when her son, King James I of England, ordered she be reinterred in Westminster Abbey. It remains there, along with at least 40 other descendants, in a chapel on the other side of the Abbey from the grave of her cousin Elizabeth. In the 1800s her tomb and that of Elizabeth I were opened to try to ascertain where James I was buried; he was ultimately found buried with Henry VII.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Dunn, Jane. Elizabeth and Mary: cousins, rivals, queens. New York: Alfred A. Knopf 2004. ISBN 9780375408984

- Lewis, Jayne Elizabeth. Mary Queen of Scots: romance and nation. London: Routledge 1998. ISBN 9780415114813

- Plaidy, Jean. Mary Queen of Scots: the fair devil of Scotland London : R. Hale; New York : G.P. Putnam, 1975. ISBN 9780399115813

- Schaefer, Carol. Mary Queen of Scots. New York, NY: Crossroad Pub 2002. ISBN 9780824519476

- Warnicke, Retha M. Mary Queen of Scots. Routledge historical biographies. London: Routledge 2006. ISBN 9780415291828

External links

- "MARY, QUEEN OF SCOTS (r. 1542-67)"History of the Monarchy observed March 15, 2007.

- "There's Something About Mary" History House observed March 18, 2006.

- "The Letters In The Casket"Ladyhedgehog observed March 18, 2007.

- "Mary, Queen of Scots" Clan Crests observed March 18, 2007.

- "Philip II, Mary Stuart, and Elizabeth" THE ONLINE LIBRARY OF LIBERTY observed March 18, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.