Hildegard of Bingen

| Hildegard of Bingen |

|---|

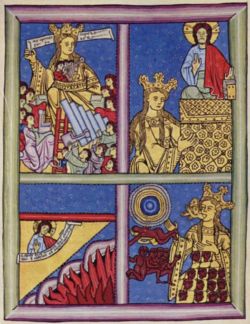

A medieval illumination showing Hildegard von Bingen and the monk Volmar.

|

| Born |

| 1098 at Böckelheim on the Nahe |

| Died |

| 17 September, 1179 Rupertsberg near Bingen |

Hildegard of Bingen (German: Hildegard von Bingen; Latin: Hildegardis Bingensis; 1098 – September 17 1179), also known as Blessed Hildegard and Saint Hildegard, was a German magistra and an abbess. Yet at a time when women were often not recognized in the public and religious sphere she was also an author, counselor, artist, physician, healer, dramatist, linguist, naturalist, philosopher, poet, political consultant, visionary, and composer of music. She wrote theological, naturalistic, botanical, medicinal, and dietary texts, also letters, liturgical songs, poems, and the first surviving morality play, while supervising brilliant miniature illuminations.[1] She was also called, the "Sibyl of the Rhine" for her prophetic visions and received many notables asking for her guidance.

Biography

Hildegard was born into a family of free nobles in the service of the counts of Sponheim, close relatives of the Hohenstaufen emperors. She was the tenth child, (the 'tithe' child) sickly from birth. From the time she was very young, Hildegard later wrote, she experienced visions. The only surviving tale of Hildegard's childhood involves a conversation that she held with her nurse, where she described an unborn calf as "white... marked with different colored spots on its forehead, feet and back." The nurse, amazed with the detail of the young child's account, told Hildegard's mother, who later rewarded her daughter with the calf, whose appearance Hildegard had accurately predicted. (Hildegard of Bingen: A Visionary Life, by Sabina Flanagan).

Perhaps due to Hildegard's visions, or as a method of political positioning, Hildegard's parents, Hildebert and Mechthilde, offered her as a tithe to the Church at the age of eight. Hildegard was placed in the care of Jutta, a wealthy anchoress (one who shuns the world and lives away from society in a closed room dedicated to religious life), the sister of Count Meinhard of Sponheim, just outside the Disibodenberg monastery in the Bavarian region now known as Germany. Jutta was enormously popular and acquired many followers, such that a small nunnery sprang up around her. Upon Jutta's, a death in 1136, Hildegard was unanimously elected as "magistra," or leader of her sister community. The election would lead to the significant move, amid great opposition, of twenty members of her community to her newly-formed monastery, St. Rupertsberg at Bingen on the Rhine in 1150, where she became abbess.

Hildegard realized that keeping her visions to herself was a wise choice, and confided them only to Jutta, who in turn told Volmar, Hildegard's tutor and, later, scribe. Throughout her life, she continued to have many visions. In 1141, she received a call from God, "Write down that which you see and hear." She was hesitant to record her visions, and soon became physically ill. In her first theological text, 'Scivias, or "Know the Ways," Hildegard describes her struggle within:

I didn’t immediately follow this command. Self-doubt made me hesitate. I analyzed others’ opinions of my decision and sifted through my own bad opinions of myself. Finally, one day I discovered I was so sick I couldn’t get out of bed. Through this illness, God taught me to listen better. Then, when my good friends Richardis and Volmar urged me to write, I did. I started writing this book and received the strength to finish it, somehow, in ten years. These visions weren’t fabricated by my own imagination, nor are they anyone else’s. I saw these when I was in the heavenly places. They are God’s mysteries. These are God’s secrets. I wrote them down because a heavenly voice kept saying to me, 'See and speak! Hear and write!' (Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader).

Hildegard's vivid description of the physical sensations which accompanied her visions have been diagnosed by neurologists, including popular author Oliver Sacks, as symptoms of migraine, although no evidence that her migraines could have produced such vast and acceptable visions is present.

The 12th century was a time of schisms and religious foment, when controversies attracted followings. Hildegard preached against schizmatics, especially the Cathars. Yet she knew her visions needed to be approved by the Catholic Church. To this end she wrote to St. Bernard, and asked for his blessing. He brought her request to the attention of Pope Eugenius (1145-53), who encouraged Hildegard to finish her writings. With papal support, Hildegard was able to finish her first work Scivias ("Know the Ways of the Lord") in ten years and thus her importance spread throughout the region.

A vita of Hildegard was written by two monks, Godfrid and Theodoric (PL vol. 197).

Works

Attention in recent decades to women of the medieval Church has led to a re-popularization of Hildegard, particularly of her music. Approximately eighty compositions have survived, which is one of the largest repertoires among medieval composers. Among her better known works, 'Ordo Virtutum',' or "Play of the Virtues," is a morality play and an example of a rare and early oratorio for women's voices, with one male part, that of the Devil, who, because of his corrupted nature, cannot sing. The play has served as an inspiration and foundation to what later became known as opera. The oratorio was created, like much of Hildegard's music, for religious ceremonial performance by the nuns of her convent. Hildegard's music is described as monophonic; that is, designed for limited instrumental accompaniment and characterized by soaring soprano vocalizations. Hildegard, in fact, remains the first composer whose biography is known.[2]

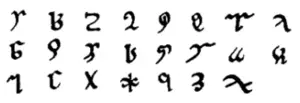

In addition to music, Hildegard also wrote medical, botanical and geological treatises, and she even invented an alternative alphabet. The text of her writing and compositions reveals Hildegard's use of this form of modified medieval Latin, encompassing many invented, conflated and abridged words. Due to her inventions of words for her lyrics and a constructed script, many conlangers (people who are immersed in specialized forms of symbolic communication) look upon her as a medieval precursor.

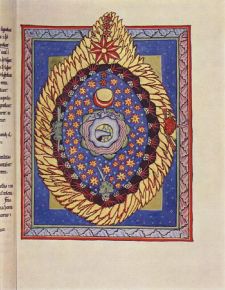

She collected her visions into three books. The first and most important Scivias ("Know the Way") was completed in 1151. Liber vitae meritorum ("Book of Life's Merits") and De operatione Dei ("Of God's Activities") also known as Liber divinorum operum ("Book of Divine Works") followed. In these volumes, written over the course of her life until her death in 1179, she first describes each vision, then interprets them. The narrative of her visions was richly decorated under her direction, presumably drawn by other nuns in the convent, while transcription assistance was provided by the monk Volmar with pictures of the visions (see him portrayed on the right of the illustration at the top of the article). Her interpretations are usually quite traditionally Catholic in nature. The book was celebrated in the Middle Ages and printed for the first time in Paris in 1513.

In her work Scivias, the visionary saint Hildegard of Bingen was one of the first to interpret the beast in the Book of Revelation as the Antichrist, a figure whose rise to power would parallel Christ's own life, but in a demonic form. For Hildegard, the source of the Antichrist's evil power lay in Judaism.

Hildegard's visionary writings maintain that virginity is the highest level of the spiritual life. She is the first woman to record a treatise of feminine sexuality, providing scientific accounts of the female orgasm.

"When a woman is making love with a man, a sense of heat in her brain, which brings with it sensual delight, communicates the taste of that delight during the act and summons forth the emission of the man's seed. And when the seed has fallen into its place, that vehement heat descending from her brain draws the seed to itself and holds it, and soon the woman's sexual organs contract, and all the parts that are ready to open up during the time of menstruation now close, in the same way as a strong man can hold something enclosed in his fist."

In addition, there are many instances, both in her letters and visions, which decry the misuse of carnal pleasures. In Scivias Book II Vision Six.78,

"God united man and woman, thus joining the strong to the weak, that each might sustain the other. But these perverted adulterers change their virile strength into perverse weakness, rejecting the proper male and female roles, and in their wickedness they shamefully follow Satan, who in his pride sought to split and divide Him Who is indivisible. They create in themselves by their wicked deeds a strange and perverse adultery, and so appear polluted and shameful in My sight..."

"...a woman who takes up devilish ways and plays a male role in coupling with another woman is most vile in My sight, and so is she who subjects herself to such a one in this evil deed..."

"...And men who touch their own genital organ and emit their semen seriously imperil their souls, for they excite themselves to distraction; they appear to Me as impure animals devouring their own whelps, for they wickedly produce their semen only for abusive pollution..."

"...When a person feels himself disturbed by bodily stimulation let him run to the refuge of continence, and seize the shield of chastity, and thus defend himself from uncleanness." (translation by Mother Columba Hart and Jane Bishop).

Significance

Hildegard was a powerful woman, who communicated with Popes such as Eugene III and Anastasius IV, statesmen such as Abbot Suger, German emperors such as Frederick I Barbarossa, and others such as Saint Bernard of Clairvaux, who advanced her work, at the behest of her abbot, Kuno, at the Synod of Trier 1147 and 1148.

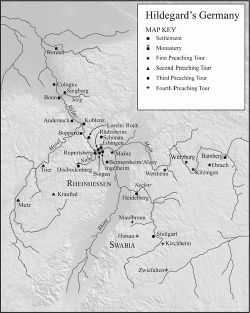

Many abbots and abbesses asked her for prayers and opinions on various matters. She traveled widely during her four preaching tours, the only woman to have done so during the Middle Ages (see Scivias, tr. Hart, Bishop, Newman).

Hildegard was one of the first souls for which the canonization process was officially applied, but the process took so long that four attempts at canonization (the last was in 1244, under Pope Innocent IV) were not completed, and she remained at the level of her beatification. She has been referred to as a saint by some, nonetheless, particularly in contemporary Rhineland, Germany.

Hildegard's name was taken up in the Roman martyrology at the end of the sixteenth century. Her feast day is September 17. Hildegard’s Parish and Pilgrimage Church house the relics of Hildegard, including an altar encasing her earthly remains, in Eibingen near Rüdesheim (on the Rhine).

As Sister Judith Sutera, O.S.B., of Mount St. Scholastica explains:

For the first centuries, the ‘naming’ and veneration of saints was an informal process, occurring locally and operating locally. . . . When they began to codify, between the thirteenth and sixteenth centuries, they did not go back and apply any official process to those persons who were already widely recognized and venerated. They simply ‘grandfathered in’ anyone whose cult had been flourishing for 100 years or more. So many quite famous, ancient, and even non-existent saints who have had feast days and devotions since the apostolic era were never canonized per se.[3]

Further reading

Selected English Translations of Hildegard

- Baird, Joseph L. and Radd K. Ehrman, trans. The Letters of Hildegard of Bingen. Vol. I, 1994, II, 1998, and III, 2004. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994.

- Butcher, Carmen Acevedo. Incandescence: 365 Readings with Women Mystics. Brewster, MA: Paraclete Press, 2005.

- Feiss, Hugh, trans. Explanation of the Rule of St. Benedict by Hildegard of Bingen. Peregrina Translation Series. 1990. Toronto: Peregrina, 1996.

- Führkötter, Adelgundis, and James McGrath. The Life of Holy Hildegard by the Monks Gottfried and Theodoric. Collegeville, MN: The Liturgical Press, 1980.

- Hart, Columba and Jane Bishop, trans. Scivias. Classics of Western Spirituality. New York: Paulist Press, 1990.

- Hozeski, Bruce W., trans. The Book of the Rewards of Life (Liber vitae meritorum). New York: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Media

"O frondens virga" From Ordo Virtutum Problems listening to this file? See media help. Notes

- ↑ For more information on Hildegard as polymath, see Carmen Acevedo Butcher's Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader (Paraclete Press, 2007).

- ↑ http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/med/hildegarde.html

- ↑ See Carmen Acevedo Butcher's Hildegard of Bingen: A Spiritual Reader (Paraclete Press, 2007), p. 160.

References

ISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Sweet, Victoria. Rooted in the Earth, Rooted in the Sky: Hildegard of Bingen and Premodern Medicine. New York: Routledge Press, 2006. ISBN 0-415-97634-0

- Baird, Joseph L. (trans.), Radd K. Ehrman. The letters of Hildegard of Bingen. New York : Oxford University Press, 3 vols., 1994-2004. ISBN 0-19-508937-5

- Baird, Joseph L. The Personal Correspondence of Hildegard of Bingen. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-19-530823-9

- Hart, Mother Columba and Bishop, Jane. (1990). Scivias:The Classics of Western Spirituality. New York/Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1990. ISBN 0-8091-3130-7

- Ekdahl Davidson, Audrey, ed. (1992). The "Ordo virtutum" of Hildegard of Bingen : critical studies. Kalamazoo, Mich.: Medieval Institute Publications, Western Michigan University, 1992. ISBN 1-879288-17-6

- Sweet, Victoria. Hildegard of Bingen and the Greening of Medieval Medicine. Bulletin of the History of Medicine, 1999, 73:381-403.

- Flanagan, Sabina. Hildegard of Bingen, a Visionary Life. Routledge, London, 1989. ISBN 0-7607-1361-8

- Fox, Matthew. Illuminations of Hildegard of Bingen. Santa Fe, N.M. : Bear & Co., 1985. ISBN 1-879181-97-5

- Hozeski, Bruce W., trans. Hildegard of Bingen : the Book of the rewards of life (Liber vitae meritorum). New York : Garland Pub., 1994. ISBN 0-19-511371-3

- Newman, Barbara. Sister of wisdom : St. Hildegard's theology of the feminine. Berkeley : University of California Press, 1987. ISBN 0-520-06615-4

- Newman, Barbara. God and the Goddesses. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 0-8122-1911-2

- Ulrich, Ingeborg. Hildegard von Bingen: Mystikerin, Heilerin, Gefahrtin der Engel. Munich: Kosel, 1990. (German) ISBN 3-466-34254-6

- Weeks, Andrew. German mysticism from Hildegard of Bingen to Ludwig Wittgenstein : a literary and intellectual history. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1993. ISBN 0-7914-1419-1

- Burnett McInerney, Maud, ed. Hildegard of Bingen: A Book of Essays. New York: Garland Pub., 1998. ISBN 0-8153-2588-6

- Chadwick, Whitney. Women, Art, and Society, Thames and Hudson, London, 1990. ISBN 0-500-20354-7

- Harris, Anne Sutherland and Linda Nochlin, Women Artists: 1550-1950, Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Knopf, New York, 1976. ISBN 0-394-73326-6

- Silvas, Anna. (trans). Jutta and Hildegard: the Biographical Sources (Brepols Medieval Women Series). Penn State University Press, 1999. ISBN 0-271-01954-9

- Boyce-Tillman, June. The Creative Spirit: Harmonious Living with Hildegard of Bingen, Harrisburg, PA: Morehouse Publishing, 2000. ISBN 0-8192-1882-0

External links

- Hildegard of Bingen website at Johannes Gutenburg University, www.hildegard.org.. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- New Advent's article on Hildegard of Bingen, www.newadvent.org.. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- The Life and Works of Hildegard von Bingen, www.fordham.edu. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- Biography and Prayers of Hildegard, www.poetseers.org. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- Discography, www.medieval.org. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- Church of St. Hildegard in Eibingen, www.eibingen.de (German). Retrieved April 21, 2007.

This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.