Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Frida Kahlo" - New World

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

==The End and The Legacy== | ==The End and The Legacy== | ||

| − | During Frida Kahlo's life she had three exhibitions: one in New York in 1938, one in Paris in 1939, and finally one in Mexico City in 1953. But by the time of her final exhibition, Kahlo's injuries were catching up to her. Her health was so bad doctors advised her not to attend. But Kahlo would not be dissuaded. Minutes after the exhibition started, a wail of sirens filled the air and an ambulance arrived. Kahlo | + | During Frida Kahlo's life she had three exhibitions: one in New York in 1938, one in Paris in 1939, and finally one in Mexico City in 1953. But by the time of her final exhibition, Kahlo's injuries were catching up to her. Her health was so bad doctors advised her not to attend. But Kahlo would not be dissuaded. Minutes after the exhibition started, a wail of sirens filled the air and an ambulance arrived. Kahlo emerged on a stretcher and was placed in the center of the gallery where she held court all evening. [http://www.myhero.com/myhero/hero.asp?hero=f_kahlo] |

In July 1954, Frida made her last public appearance when she participated in a Communist demonstration protesting the U.S. subversion of the left-wing Guatemalan government and the overthrow of its president, Jacobo Arbenz. Soon afterwards, she died in her sleep, apparently as the result of an embolism, though there was a suspicion among those close to her that she had found a way to commit suicide. Her last diary entry read: "I hope the end is joyful - and I hope never to come back - Frida." [http://www.artchive.com/artchive/K/kahlo.html] | In July 1954, Frida made her last public appearance when she participated in a Communist demonstration protesting the U.S. subversion of the left-wing Guatemalan government and the overthrow of its president, Jacobo Arbenz. Soon afterwards, she died in her sleep, apparently as the result of an embolism, though there was a suspicion among those close to her that she had found a way to commit suicide. Her last diary entry read: "I hope the end is joyful - and I hope never to come back - Frida." [http://www.artchive.com/artchive/K/kahlo.html] | ||

| Line 88: | Line 88: | ||

Feminists might celebrate Kahlo's ascent to greatness, if only her fame were related to her art. Instead, her fans are largely drawn by the story of her life, for which her paintings are often presented as simple illustration. Her admirers are inspired by Kahlo's tragic tale of physical suffering and fascinated with her glamorous friends and lovers, among them photographer and Soviet spy Tina Modotti and Leon Trotsky. | Feminists might celebrate Kahlo's ascent to greatness, if only her fame were related to her art. Instead, her fans are largely drawn by the story of her life, for which her paintings are often presented as simple illustration. Her admirers are inspired by Kahlo's tragic tale of physical suffering and fascinated with her glamorous friends and lovers, among them photographer and Soviet spy Tina Modotti and Leon Trotsky. | ||

| − | Since her rediscovery in the 1970s, one of the few people to openly criticize Kahlo for her politics was her fellow countryman, the late Nobel laureate Octavio Paz. In ''Essays on Mexican Art'', he questions whether someone could be both a great artist and "a despicable cur." In the end, he says they can, but suggests that, because of the way they embraced Stalin, "Diego and Frida ought not to be subjects of beatification but objects of study—and of repentance . . . the weaknesses, taints, and defects that show up in the works of Diego and Frida are moral in origin. The two of them betrayed their great gifts, and this can be seen in their painting. An artist may commit political errors and even common crimes, but the truly great artists—Villon or Pound, Caravaggio or Goya—pay for their mistakes and thereby redeem their art and their honor." [http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2001/0206.mencimer.html]<ref>Paz, Octavio ''Essays on Mexican Art'', NY: Harcourt, 1995 ISBN 015600061X </ref>. | + | Since her rediscovery in the 1970s, one of the few people to openly criticize Kahlo for her politics was her fellow countryman, the late Nobel laureate Octavio Paz. In ''Essays on Mexican Art'', he questions whether someone could be both a great artist and "a despicable cur." In the end, he says they can, but suggests that, because of the way they embraced Stalin, <blockquote>"Diego and Frida ought not to be subjects of beatification but objects of study—and of repentance . . . the weaknesses, taints, and defects that show up in the works of Diego and Frida are moral in origin. The two of them betrayed their great gifts, and this can be seen in their painting. An artist may commit political errors and even common crimes, but the truly great artists—Villon or Pound, Caravaggio or Goya—pay for their mistakes and thereby redeem their art and their honor." [http://www.washingtonmonthly.com/features/2001/0206.mencimer.html] <ref>Paz, Octavio ''Essays on Mexican Art'', NY: Harcourt, 1995 ISBN 015600061X </ref>. </blockquote> |

== External links == | == External links == | ||

Revision as of 21:46, 2 September 2006

Magdalena Carmen Frida Kahlo y Calderón de Rivera, better known as Frida Kahlo (July 6, 1907 to July 13, 1954), was a Mexican painter of the indigenous culture of her country in a style combining Realism, Symbolism and Surrealism. She was the wife of the Mexican muralist and cubist painter Diego Rivera.

Kahlo's life was one marked by suffering, heroism, and genius. Stricken with polio as a child, then nearly crippled in a bus accident at the age of eighteen, Kahlo defied the odds, not only by learning to walk again, but by taking the world by storm with her unique artistic vision.[1]

During her life, Kahlo was recognized primarily by the intellectual elite, both in Mexico and internationally, but was not well known among ordinary Mexicans, particularly because she worked in mediums that did not lend themselves to mass distribution. [2]

A child during the Mexican Revolution, Kahlo grew up in an era of social change. In the 1920s Frida espoused a Communist, anti-capitalist, philosophy, She befriended the famed Bolshevik revolutionary and Marxist theorist, Leon Trostky, who was assassinated in her home country of Mexico.

Known for her unconventional appearance and flamboyant Mexican clothing, Ms. Kahlo accomplished much in her short tragic life. To the public she was a high spirited rebellious woman. Her creative style was breathtaking yet bewildering. She was possibly the most idolized woman artist of her time. [3]

Today, she is a figure eliciting widely contrasting opinions. To some, she was a woman of legendary power who overcame incredible odds, whose work inspires excitement and awe. To others, she was a public figure of highly questionable morals and politics who betrayed her gifts and celebrity.

Family and Childhood

Kahlo was born Magdalena Carmen Frieda Kahlo y Calderón in her parents' house in Coyoacán, which at the time was a small town on the outskirts of Mexico City.

Heritage

Frida's father, of Hungarian Jewish descent, was born Wilhelm Kahlo in Baden-Baden, Germany, in 1872. At the age of nineteen he moved to Mexico City and began a new life by changing his name to its Spanish equivalent - Guillermo. He never returned to Germany.

In 1898 Guillermo married Matilde Calderon, a woman of Spanish and Native American descent. Frida was the third of four daughters born of their marriage. [4]

Frida later claimed she was born in 1910 in order to affiliate herself further with being a product of the Mexican Revolution, which began in 1910. [5]

Health

Kahlo's life was marked by tragedy. At the age of seven she was stricken with polio and was left with one leg being smaller and thinner than the other. Still, with her father's encouragement and with the feisty and brash personality that she kept throughout her life, she overcame her disability.

At the age of 18 Kahlo was involved in a horrendous streetcar - bus accident. Not only was her lower body impaled on a metal rod, she broke her collarbone, her pelvis, several ribs and also her spine in three places. Her right leg had eleven fractures and her right foot was crushed and dislocated. For the second time in her life, she had to re-learn to walk.

Throughout her life she was plagued by relapses of extreme pain, often leaving her hospitalized and/or in bed for months at a time, agonized and miserable. Frida would undergo as many as thirty-five operations in her life as a result of the accident, mainly on her back and her right leg or foot.

During her life she suffered three miscarriages, thought to be caused by her prior injuries. Later in life she developed more severe complications and suffered a gangrenous leg, which had to be amputated. [6]

Casa Azul

Frida Kahlo was born, lived, and died in her Casa Azul (Blue House) in Coyoacán, Mexico. The valley of Mexico is very fertile, therefore her house was filled with flora, trees, and cacti. [7]

A cheerful home populated by pre-Columbian idols and luxuriant tropical plantings, painted inside and out in cobalt blue with bright yellow floors, the family home provided a cheerful backdrop for a child with much physical suffering. This is the home where she was born, grew up and later lived with her husband Diego Rivera, from 1941 until her death at age 47 in 1954.

After Frida's death, Rivera gave the Casa Azul and its contents to the Mexican people, it opened as a museum four years later, in 1958. Now known as the Frida Kahlo Museum, this bit of pure Mexicanista is hidden behind high cobalt blue walls in a charming southwestern suburb of Mexico City, Ms. Kahlo's birthplace. [8]

The Adult Frida

It is impossible to study Frida Kahlo's artistry, marriage, morals and politics in separate veins. These aspects of her life were intricately intermingled, each affecting the other.

The Artist

During Kahlo's long recuperation from the bus accident, she discovered her love for painting. Using a lap easel her mother gave her and a mirror she'd had hung in the canopy above her bed, Kahlo produced some of her earliest self-portraits. [9]

Before this time, Kahlo had planned on a medical career, but gave it up for a full-time career in painting. Drawing on her personal experiences such as her troubled marriage, her painful miscarriages and her numerous operations, her works are often shocking in their stark portrayal of pain.

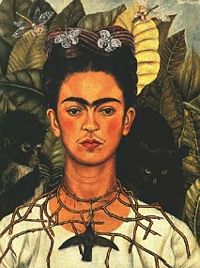

Fifty-five of Kahlo's 143 paintings are self-portraits, often incorporating symbolic portrayal of her physical and psychological wounds. She was deeply influenced by indigenous Mexican culture, which surfaced in her paintings' bright colors, dramatic symbolism, and unapologetic rendering of often harsh and gory content.

Frida, the person and her art, defy easy definition. Rather, they lend themselves to ambiguous description. Often volatile and obsessive, Frida was alternately hopeful and despairing. [10] Although her work is sometimes classified as surrealist, and she did exhibit several times with European surrealists, she did not consider herself one. "They thought I was a Surrealist, but I wasn't. I never painted dreams. I painted my own reality." she once said.

Like much of Mexican art, Frida's paintings "interweave fact and fantasy as if the two were inseparable and equally real," Hayden Herrera, her principal biographer stated. [11]

Gregorio Luke, Director of the Museum of Latin American Art, explained, "Her work was very inclusive. She was able to incorporate elements of pop culture, Indian, Aztec mythology, surrealism, a whole variety of things in which many people can identify. She is the multicultural artist par excellence." [12]

Kahlo's preoccupation with female themes and the figurative candor with which she expressed them made her something of a feminist cult figure in the last decades of the 20th century, though she was little known outside the world of art until the 1990's.

Married Life

Frida married the famed artist Diego Rivera in August 1929. She was 22 years old and he was 42. Rivera's second marriage had recently disintegrated, and the two found that they had much in common, not least from a political point of view, since both were now communist militants. [13]

While they remained residents of Mexico City, because Rivera was commissioned to do murals in the United States, they lived in San Francisco, Detroit, and New York while he worked on those commissions. [14] When they finally returned to Mexico in 1935, Rivera embarked on an affair with Kahlo's younger sister Cristina. Though they finally made up their quarrel, this incident marked a turning point in their relationship. Rivera had never been faithful to any woman; Kahlo now embarked on a series of affairs with both men and women which were to continue for the rest of her life. Rivera tolerated her lesbian relationships better than he did the heterosexual ones, which made him violently jealous. One of Kahlo's more serious early love affairs was with the Russian revolutionary leader Leon Trotsky, now being hounded by his triumphant rival Stalin, and who had been offered refuge in Mexico in 1937 on Rivera's initiative. [15]

Needless to say, theirs was an unconventional and problematic, if passionate, union that survived numerous affairs on both their parts, separations and even a divorce in 1939 and subsequent remarriage in 1940. Frida's hold on Diego as a husband was tenuous. Diego's incorrigible philandering only exacerbated her pain. "I suffered two grave accidents in my life," she once said, "One in which a streetcar knocked me down … The other accident is Diego."

As a couple, the Riveras remained childless; this, as much as Diego's infidelities, was a source of great anguish for Frida for whom Diego was everything: "my child, my lover, my universe."

As individual artists, the pair was wildly productive. Each regarded the other as Mexico's greatest painter. Frida referred to Diego as the "architect of life." Each took a deep, proprietary pride in the other's creations, drastically different as they were in habit and style. [16]

Frida Kahlo was described as a vibrant, extroverted character whose everyday speech was filled with profanities. She had been a tomboy in her youth and carried her fervor throughout her life. She was a heavy smoker, drank liquor (especially tequila) in excess, was openly bisexual, sang off-color songs, and told equally ribald jokes to the guests of the wild parties that she hosted.

Politics

Both Kahlo and Rivera were active in the Communist Party and Mexican politics. More importantly, when Kahlo met Rivera, he was a leading proponent of a post-revolutionary movement known as Mexicanidad, which rejected Western European influences and the "easel art" of the aristocracy in favor of all things considered "authentically" Mexican, such as peasant handicrafts and pre-Columbian art. Kahlo also became a diehard adherent, adopting her now-famous traditional Mexican costumes—long skirts and dresses, which also had the practical effect of covering up her polio-withered leg. Rejecting, too, conventional standards of beauty, Kahlo not only didn't pluck her heavy eyebrows or mustache, she groomed them with special tools and even penciled them darker.

More importantly, though, Kahlo's Communism—now treated as somehow sort of quaint—led her to embrace some unforgivable political positions. In 1936, Rivera, a dedicated Trotskyite, used his clout to petition the Mexican government to give Trotsky and his wife asylum after they were forced out of Norway. Rivera and Kahlo put up the Trotskys in Kahlo's family home, where Kahlo seduced the older man.

After Trotsky was assassinated, however, Kahlo turned on her old lover with a vengeance, claiming in an interview that Trotsky was a coward and had stolen from her while he stayed in her house (which wasn't true). Rarely is this unflattering detail included in the condensed Kahlo story. Nor is the fact that Kahlo turned on Trotsky because she had become a devout Stalinist. Kahlo continued to worship Stalin even after it had become common knowledge that he was responsible for the deaths of millions of people, not to mention Trotsky himself. One of Kahlo's last paintings was called "Stalin and I," and her diary is full of her adolescent scribblings ("Viva Stalin!") about Stalin and her desire to meet him. [17]

The End and The Legacy

During Frida Kahlo's life she had three exhibitions: one in New York in 1938, one in Paris in 1939, and finally one in Mexico City in 1953. But by the time of her final exhibition, Kahlo's injuries were catching up to her. Her health was so bad doctors advised her not to attend. But Kahlo would not be dissuaded. Minutes after the exhibition started, a wail of sirens filled the air and an ambulance arrived. Kahlo emerged on a stretcher and was placed in the center of the gallery where she held court all evening. [18]

In July 1954, Frida made her last public appearance when she participated in a Communist demonstration protesting the U.S. subversion of the left-wing Guatemalan government and the overthrow of its president, Jacobo Arbenz. Soon afterwards, she died in her sleep, apparently as the result of an embolism, though there was a suspicion among those close to her that she had found a way to commit suicide. Her last diary entry read: "I hope the end is joyful - and I hope never to come back - Frida." [19]

Frida Kahlo leaves behind a mixed legacy: she is both greatly admired and starkly criticized.

Feminists might celebrate Kahlo's ascent to greatness, if only her fame were related to her art. Instead, her fans are largely drawn by the story of her life, for which her paintings are often presented as simple illustration. Her admirers are inspired by Kahlo's tragic tale of physical suffering and fascinated with her glamorous friends and lovers, among them photographer and Soviet spy Tina Modotti and Leon Trotsky.

Since her rediscovery in the 1970s, one of the few people to openly criticize Kahlo for her politics was her fellow countryman, the late Nobel laureate Octavio Paz. In Essays on Mexican Art, he questions whether someone could be both a great artist and "a despicable cur." In the end, he says they can, but suggests that, because of the way they embraced Stalin,

"Diego and Frida ought not to be subjects of beatification but objects of study—and of repentance . . . the weaknesses, taints, and defects that show up in the works of Diego and Frida are moral in origin. The two of them betrayed their great gifts, and this can be seen in their painting. An artist may commit political errors and even common crimes, but the truly great artists—Villon or Pound, Caravaggio or Goya—pay for their mistakes and thereby redeem their art and their honor." [20] [1].

External links

- The Life and Art of Frida Kahlo

- "The Frida Kahlo Museum", by Gale Randall

- Exhibition guide from Tate Modern

- Frida's House Yahoo! group

- "Frida Kahlo & contemporary thought"

- "Frida by Kahlo"

- "Frida Kahlo" at ArtCyclopedia

- "Dolor y arte: Frida Kahlo" from Psikeba Magazine

- Ten Dreams Galleries

- Photos

Notes

- ↑ Paz, Octavio Essays on Mexican Art, NY: Harcourt, 1995 ISBN 015600061X

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.