Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Alice Paul" - New World

Laura Brooks (talk | contribs) (→Career) |

|||

| Line 6: | Line 6: | ||

==Early Life== | ==Early Life== | ||

| − | Alice was born to William and Tacie Paul on January 11, 1885. They were a Quaker family living on the family farm in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. In 1901, she graduated first in her class from the Moorestown Friends School. She later attended Swarthmore College (BA, 1905), the New York School of Philanthropy (social work), and the University of Pennsylvania (MA, sociology). In 1907, Paul moved to [[United Kingdom|England]] where she attended the University of Birmingham and the London School of Economics (LSE). Returning to the [[United States]] in 1910, she attended the University of Pennsylvania, completing a PhD in political science in 1912. Her dissertation topic was: ''The Legal Position of Women in Pennsylvania''. In 1927, she received an LLM followed by a Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1928, both from American University's Washington College of Law. | + | Alice was born to William and Tacie Paul on January 11, 1885. They were a Quaker family living on the family farm in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. William was a banker and businessman, serving as president of the Burlington County Trust Company. Alice had two brothers, William Jr. and Parry, and a sister, Helen. As Hixsite Quakers, the family believed in gender equality, education for women, and working for the betterment of society. Tacie often brought Alice to her women's suffrage meetings. |

| + | |||

| + | In 1901, she graduated first in her class from the Moorestown Friends School. She later attended Swarthmore College (BA, 1905), the New York School of Philanthropy (social work), and the University of Pennsylvania (MA, sociology). In 1907, Paul moved to [[United Kingdom|England]] where she attended the University of Birmingham and the London School of Economics (LSE). Returning to the [[United States]] in 1910, she attended the University of Pennsylvania, completing a PhD in political science in 1912. Her dissertation topic was: ''The Legal Position of Women in Pennsylvania''. In 1927, she received an LLM followed by a Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1928, both from American University's Washington College of Law. | ||

==Career== | ==Career== | ||

| − | While she was in England in 1908, Paul heard | + | While she was in [[United Kingdom|England]] in 1908, Paul heard Christabel Pankhurst speak at the University of Birmingham. Inspired, Paul joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), where she met fellow American Lucy Burns. Her activities with the WSPU led to her arrest and imprisonment three times. Along with other suffragists she went on hunger strike and was force-fed. |

| − | In 1912, Alice Paul joined the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and was appointed Chairman of their Congressional Committee in Washington, DC. | + | In 1912, Alice Paul joined the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and was appointed Chairman of their Congressional Committee in Washington, DC. After months of fundraising and raising awareness for the cause, membership numbers went up and, in 1913, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns formed the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage. Their focus was lobbying for a constitutional amendment to secure the right to vote for women. Such an amendment had originally been sought by suffragists [[Susan B. Anthony]] and [[Elizabeth Cady Stanton]] in 1878. However, by the early twentieth century, attempts to secure a federal amendment had ceased. The focus of the suffrage movement had turned to securing the vote on a state-by-state basis.[[Image:alice_paul.jpg|thumb|left|205px|Alice Paul]] |

| − | When their lobbying efforts proved fruitless, Paul and her colleagues formed the | + | When their lobbying efforts proved fruitless, Paul and her colleagues formed the National Woman's Party (NWP) in 1916 and began introducing some of the methods used by the suffrage movement in Britain. |

| + | Alice organized the largest parade ever seen on March 3, 1913, the eve of President [[Woodrow Wilson]]’s inauguration. About 8,000 college, professional, middle- and working-class women dressed in white suffragist costumes marched in units with banners and floats down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the White House. The goal was to gather at the Daughters of the American Revolution's Constitution Hall. The crowd was estimated at half a million people, with many verbally harassing the marchers while police stood by. Troops finally had to be called to restore order and help the suffragists get to their destination — it took six hours. | ||

| − | In the election of 1916, Paul and the NWP campaigned against the continuing refusal of President [[Woodrow Wilson]] and other incumbent [[United States Democratic Party|Democrats]] to actively support the Suffrage Amendment. In January 1917, the NWP staged the first political protest ever to [[picketing|picket]] the [[White House]]. The picketers, known as "Silent Sentinels," held banners demanding the right to vote. This was an example of a | + | The parade generated more publicity than Alice could have hoped for. Newspapers carried articles for weeks, with politicians demanding investigations into police practices in Washington, and commentaries on the bystanders. The publicity opened the door for the Congressional Committee to lobby congressmen, and the president. On March 17, Alice and other suffragists met with President Wilson, who appeared mildly interested but feigned ignorance and said the time was not right yet. They met two more times that month. She organized another demonstration on April 7, opening day of the new Congress. Also in April, Alice established the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CUWS), sanctioned by NAWSA and dedicated to achieving the federal amendment. By June, the Senate Committee on Women's Suffrage reported favorably on the amendment and senators prepared to debate the issue for the first time since 1887. |

| + | |||

| + | In the election of 1916, Paul and the NWP campaigned against the continuing refusal of President [[Woodrow Wilson]] and other incumbent [[United States Democratic Party|Democrats]] to actively support the Suffrage Amendment. In January 1917, the NWP staged the first political protest ever to [[picketing|picket]] the [[White House]]. The picketers, known as "Silent Sentinels," held banners demanding the right to vote. This was an example of a non-violent civil disobedience campaign. In July 1917, picketers were arrested on charges of "obstructing traffic." Many, including Paul, were convicted and incarcerated at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia (now the Lorton Correctional Complex) and the District of Columbia Jail. | ||

In protest of the conditions in Occoquan, Paul commenced a hunger strike. This led to her being moved to the prison’s psychiatric ward and force-fed. Other women joined the strike, which combined with the continuing demonstrations and attendant press coverage, kept the pressure on the Wilson administration. In January, 1918, the president announced that women's suffrage was urgently needed as a "war measure." | In protest of the conditions in Occoquan, Paul commenced a hunger strike. This led to her being moved to the prison’s psychiatric ward and force-fed. Other women joined the strike, which combined with the continuing demonstrations and attendant press coverage, kept the pressure on the Wilson administration. In January, 1918, the president announced that women's suffrage was urgently needed as a "war measure." | ||

| − | [[Image:Alice Paul stamp.gif|thumb|175px|Alice Paul depicted on a United States stamp. See | + | [[Image:Alice Paul stamp.gif|thumb|175px|Alice Paul depicted on a United States stamp. See Great Americans series.]] |

| − | In 1920 the | + | In 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution secured the vote for women. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Paul was the original author of a proposed [[Equal Rights Amendment]] to the Constitution in 1923. She opposed linking the ERA to [[abortion]] rights, as did most early feminists. It has been widely reported that Paul called abortion "the ultimate exploitation of women." However, there appears to be no record of her making this statement. On the other hand, there is documentation that strongly suggests that although she did not want the ERA to be linked with abortion, it was for political, rather than ideological or moral, reasons. An article in ''The Touchstone'' (2000) provides the following commentary on the relationship between the ERA and her views on abortion: | |

| − | + | <blockquote>Alice Paul did oppose the linkage between the ERA and abortion, but that was because of her political astuteness rather than any disagreement with abortion. Paul felt that by linking the ERA with abortion, the ERA would not pass through Congress. Willis wrote, "She did not address issues of birth control, i.e., abortion, or even women's sexuality, and was concerned that the radical women of the 1960's might alienate support by emphasizing these issues...[S]he said that even if women did want to do many things that she wished they would not do with their freedom, it was not her business to tell them what to do with it, but to see that they had it."</blockquote> | |

| − | + | Although no documentation of Alice Paul's actual views exist apart from the Suffragist Oral History Project, according to Pat Goltz, Feminists for Life cofounder, who spoke with her in the late seventies, and Evelyn Judge, a life long friend, Alice Paul did indeed oppose abortion, and even referred to it once as "killing unborn women." | |

| − | + | In 2004, HBO Films broadcast "Iron Jawed Angels," chronicling the struggle of Alice Paul (portrayed by Hilary Swank) and other suffragists. In 2005, her alma mater, Swarthmore College, named its newest student dormitory in honor of Alice Paul after a donor agreed to select one of the top few student-provided suggestions. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

*Raum, Elizabeth ''Alice Paul'' (American Lives) NY: Heinemann, 2004 ISBN 1403457034 | *Raum, Elizabeth ''Alice Paul'' (American Lives) NY: Heinemann, 2004 ISBN 1403457034 | ||

* Butler, Amy E''Two Paths to Equality: Alice Paul and Ethel M Smith'', Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002 ISBN 0791453200 | * Butler, Amy E''Two Paths to Equality: Alice Paul and Ethel M Smith'', Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002 ISBN 0791453200 | ||

| − | + | * Commire, Anne, editor. Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, Conn.: Yorkin Publications, 1999-2000 ISBN 078764062X | |

| + | * Evans, Sara M. Born for Liberty. The Free Press: Macmillan, N.Y. 1989 ISBN 0029029902 | ||

| + | * Scott, Anne Firor and Andrew MacKay Scott. One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage. Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA. 1975 ISBN 0397473338 | ||

| + | * Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill, editor. One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. NewSage Press: Troutdale, OR. 1995 ISBN 0939165260 | ||

Revision as of 20:50, 13 December 2006

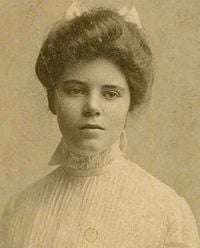

Alice Stokes Paul (January 11, 1885 – July 9, 1977) was an American suffragist leader. Along with Lucy Burns (a close friend) and others, she led a successful campaign for women's suffrage that resulted in granting the right to vote to women in the U.S. federal election in 1920.

Early Life

Alice was born to William and Tacie Paul on January 11, 1885. They were a Quaker family living on the family farm in Mount Laurel, New Jersey. William was a banker and businessman, serving as president of the Burlington County Trust Company. Alice had two brothers, William Jr. and Parry, and a sister, Helen. As Hixsite Quakers, the family believed in gender equality, education for women, and working for the betterment of society. Tacie often brought Alice to her women's suffrage meetings.

In 1901, she graduated first in her class from the Moorestown Friends School. She later attended Swarthmore College (BA, 1905), the New York School of Philanthropy (social work), and the University of Pennsylvania (MA, sociology). In 1907, Paul moved to England where she attended the University of Birmingham and the London School of Economics (LSE). Returning to the United States in 1910, she attended the University of Pennsylvania, completing a PhD in political science in 1912. Her dissertation topic was: The Legal Position of Women in Pennsylvania. In 1927, she received an LLM followed by a Doctor of Civil Law degree in 1928, both from American University's Washington College of Law.

Career

While she was in England in 1908, Paul heard Christabel Pankhurst speak at the University of Birmingham. Inspired, Paul joined the Women's Social and Political Union (WSPU), where she met fellow American Lucy Burns. Her activities with the WSPU led to her arrest and imprisonment three times. Along with other suffragists she went on hunger strike and was force-fed.

In 1912, Alice Paul joined the National American Women's Suffrage Association (NAWSA) and was appointed Chairman of their Congressional Committee in Washington, DC. After months of fundraising and raising awareness for the cause, membership numbers went up and, in 1913, Alice Paul and Lucy Burns formed the Congressional Union for Women Suffrage. Their focus was lobbying for a constitutional amendment to secure the right to vote for women. Such an amendment had originally been sought by suffragists Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton in 1878. However, by the early twentieth century, attempts to secure a federal amendment had ceased. The focus of the suffrage movement had turned to securing the vote on a state-by-state basis.

When their lobbying efforts proved fruitless, Paul and her colleagues formed the National Woman's Party (NWP) in 1916 and began introducing some of the methods used by the suffrage movement in Britain. Alice organized the largest parade ever seen on March 3, 1913, the eve of President Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. About 8,000 college, professional, middle- and working-class women dressed in white suffragist costumes marched in units with banners and floats down Pennsylvania Avenue from the Capitol to the White House. The goal was to gather at the Daughters of the American Revolution's Constitution Hall. The crowd was estimated at half a million people, with many verbally harassing the marchers while police stood by. Troops finally had to be called to restore order and help the suffragists get to their destination — it took six hours.

The parade generated more publicity than Alice could have hoped for. Newspapers carried articles for weeks, with politicians demanding investigations into police practices in Washington, and commentaries on the bystanders. The publicity opened the door for the Congressional Committee to lobby congressmen, and the president. On March 17, Alice and other suffragists met with President Wilson, who appeared mildly interested but feigned ignorance and said the time was not right yet. They met two more times that month. She organized another demonstration on April 7, opening day of the new Congress. Also in April, Alice established the Congressional Union for Woman Suffrage (CUWS), sanctioned by NAWSA and dedicated to achieving the federal amendment. By June, the Senate Committee on Women's Suffrage reported favorably on the amendment and senators prepared to debate the issue for the first time since 1887.

In the election of 1916, Paul and the NWP campaigned against the continuing refusal of President Woodrow Wilson and other incumbent Democrats to actively support the Suffrage Amendment. In January 1917, the NWP staged the first political protest ever to picket the White House. The picketers, known as "Silent Sentinels," held banners demanding the right to vote. This was an example of a non-violent civil disobedience campaign. In July 1917, picketers were arrested on charges of "obstructing traffic." Many, including Paul, were convicted and incarcerated at the Occoquan Workhouse in Virginia (now the Lorton Correctional Complex) and the District of Columbia Jail.

In protest of the conditions in Occoquan, Paul commenced a hunger strike. This led to her being moved to the prison’s psychiatric ward and force-fed. Other women joined the strike, which combined with the continuing demonstrations and attendant press coverage, kept the pressure on the Wilson administration. In January, 1918, the president announced that women's suffrage was urgently needed as a "war measure."

In 1920 the Nineteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution secured the vote for women.

Paul was the original author of a proposed Equal Rights Amendment to the Constitution in 1923. She opposed linking the ERA to abortion rights, as did most early feminists. It has been widely reported that Paul called abortion "the ultimate exploitation of women." However, there appears to be no record of her making this statement. On the other hand, there is documentation that strongly suggests that although she did not want the ERA to be linked with abortion, it was for political, rather than ideological or moral, reasons. An article in The Touchstone (2000) provides the following commentary on the relationship between the ERA and her views on abortion:

Alice Paul did oppose the linkage between the ERA and abortion, but that was because of her political astuteness rather than any disagreement with abortion. Paul felt that by linking the ERA with abortion, the ERA would not pass through Congress. Willis wrote, "She did not address issues of birth control, i.e., abortion, or even women's sexuality, and was concerned that the radical women of the 1960's might alienate support by emphasizing these issues...[S]he said that even if women did want to do many things that she wished they would not do with their freedom, it was not her business to tell them what to do with it, but to see that they had it."

Although no documentation of Alice Paul's actual views exist apart from the Suffragist Oral History Project, according to Pat Goltz, Feminists for Life cofounder, who spoke with her in the late seventies, and Evelyn Judge, a life long friend, Alice Paul did indeed oppose abortion, and even referred to it once as "killing unborn women."

In 2004, HBO Films broadcast "Iron Jawed Angels," chronicling the struggle of Alice Paul (portrayed by Hilary Swank) and other suffragists. In 2005, her alma mater, Swarthmore College, named its newest student dormitory in honor of Alice Paul after a donor agreed to select one of the top few student-provided suggestions.

External links

- The Alice Paul Institute

- Alice Paul at Lakewood Public Library: Women In History

- The Sewall-Belmont House & Museum—Home of the historic National Woman's Party]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Lunardini, Christine A From Equal Suffrage to Equal Rights: Alice Paul and the National Woman's Party, 1910-1928, Lincoln, NE: iUniverse, 2000 ISBN 059500055X

- Raum, Elizabeth Alice Paul (American Lives) NY: Heinemann, 2004 ISBN 1403457034

- Butler, Amy ETwo Paths to Equality: Alice Paul and Ethel M Smith, Albany: State University of New York Press, 2002 ISBN 0791453200

- Commire, Anne, editor. Women in World History: A Biographical Encyclopedia. Waterford, Conn.: Yorkin Publications, 1999-2000 ISBN 078764062X

- Evans, Sara M. Born for Liberty. The Free Press: Macmillan, N.Y. 1989 ISBN 0029029902

- Scott, Anne Firor and Andrew MacKay Scott. One Half the People: The Fight for Woman Suffrage. Lippincott: Philadelphia, PA. 1975 ISBN 0397473338

- Wheeler, Marjorie Spruill, editor. One Woman, One Vote: Rediscovering the Woman Suffrage Movement. NewSage Press: Troutdale, OR. 1995 ISBN 0939165260

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.