Yurt

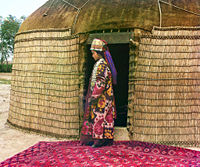

A Yurt or Ger is a portable, felt-covered, wood lattice-framed dwelling structure used by nomads in the steppes of Central Asia.

Origin

The word Yurt is originally from the Turkic word meaning "dwelling place" in the sense of "homeland"; the term came to be used in reference to the physical tent-like structures only in other languages. In Russian the structure is called yurta (юрта), whence the word came into English.

In Kazakh (and Uyghur) the term for the structure is kiyiz üy (киіз үй, lit. "felt home"). In Kyrgyz the term is boz üý (боз үй), literally "grey house," because of the color of the felt used in its construction. In Mongolian it is called a ger (гэр). Afghans call them "Kherga"/"Jirga" or "ooee." In Pakistan it is also known as gher (گھر). In Hindi, it is called ghar (घर). The original word for nomad came from a word for felt, making them the "felt people."[1]

The similarly structured Yaranga is a traditional mobile home of some nomadic Chukchi and Siberian Yupik in the Northern part of Russia. The word yaranga comes from the Chukchi language. In Russian use, the terms chum (a tent-like structure similar to Native American tipis used by Nenets people in Russia), Yurt, and Yaranga may be used indiscriminately.

Early people living in harsh climates developed the yurt from the materials available to them. Their sheep's wool was worked into felt mats which were tied to the roof and walls, made from saplings, with ropes made from animal hair. Extra mats could be added in winter for additional warmth; they could be removed in summer to allow airflow in hot weather.[1]

Construction

Traditional yurts consist of a circular wooden frame carrying a felt cover. The felt is made from the wool of the flocks of sheep that accompany the pastoralists. The timber to make the external structure is not to be found on the treeless steppes, and must be traded for in the valleys below.

The frame consists of one or more lattice wall-sections, a door-frame, roof poles and a crown. Some styles of yurt have one or more columns to support the crown. The (self-supporting) wood frame is covered with pieces of felt. Depending on availability, the felt is additionally covered with canvas and/or sun-covers. The frame is held together with one or more ropes or ribbons. The structure is kept under compression by the weight of the covers, sometimes supplemented by a heavy weight hung from the center of the roof. They vary regionally, with straight or bent roof-poles, different sizes, and relative weight.

Out of necessity, the yurt was made from locally available wool felt and designed to be dismantled and the parts carried on camels or yaks to be rebuilt on another site.

The yurt is distinguished by its unique roof construction. The wood frame consists of long spans that have no immediate support, creating an open, airy space and the hole or skylight in the center of the roof allows sunlight to enter.[1]

The circular design of the yurt is perfect for nomadic lifestyles, encompassing the maximum amount of internal space for the amount of materials used to construct it. It also leaves the least amount of exterior surface exposed to the elements, making it the most efficient to heat and the best able to withstand strong winds and storms safely.[1]

Modern fabric-covered yurts are simple to construct with a few common wood-working tools. They are easy to erect and can be taken down in an hour. They are also low-impact causing no permanent damage to the land on which they are erected.[2]

Use

For centuries, people throughout Central Asia used yurts as their homes. They are cool in summer and with a stove are easily warmed in winter. Humanitarian aid organizations provide yurts to families suffering from inadequate shelter due to extreme poverty. A ger protects a family in Mongolia from the cold temperatures and icy winds that whip across their barren homeland better than western-style rectangular shacks.[3]

One of the oldest forms of indigenous shelter still in use today, yurts have been modernized to become available and popular for a variety of uses in the twenty-first century. From campgrounds in national parks to modern offices and homes, even restaurants, contemporary uses of the versatile yurt are still evolving:

The yurt is a gift, an ancient nomadic shelter only recently available to modern culture. Versatile, beautiful and spiritual, both ancient and contemporary versions provide an option for shelter that is affordable, accessible and gentle to the earth. By its very existence, the yurt calls forth life in simplicity, in community, and in harmony with the planet.[1]

Symbolism

- Coat of arms of Kazakhstan (flat).svg

Kazakh coat of arms

The wooden lattice crown of the yurt, the shangrak (Mongolian: тооно, toono; Kazakh: Шаңырақ, shangyraq; Kyrgyz: түндүк, tunduk) is itself emblematic in many Central Asian cultures. In old Kazakh communities, the yurt itself would often be repaired and rebuilt, but the shangrak would remain intact, passed from father to son upon the father's death. A family's length of heritage could be measured by the accumulation of stains on the shangrak from generations of smoke passing through it. A stylized version of the crown is in the center of the Coat of arms of Kazakhstan, and forms the main image on the flag of Kyrgyzstan.

The Yurt is more than just a means of shelter for Mongolian tribes. They are sacred places, expressing the world views of people living in close connection with the cycles of life. The embrace of the round space gives a sense of well-being and wholeness. Bringing people together in a circle fosters connection and equality.[1]

Variations

The traditional yurt or ger continues to be commonly used in many parts of Central Asia and northern Europe. Additionally, enthusiasts in other countries have taken the visual idea of the yurt—a round, semi-permanent tent—and have adapted it to their cultural needs. Although those structures may be copied to some extent from the originals found in Central Asia, they have been greatly changed and adapted and are in most cases very different.

Yaranga

Yaranga is a tent-like traditional mobile home of some nomadic Northern indigenous peoples of Russia, such as Chukchi and Siberian Yupik. They are built of a light wooden frame, cone-shaped or rounded, and covered with reindeer hides sewn together.[4] A medium-size yaranga requires about 50 skins. A large yaranga is hard to heat completely in winter; there is a smaller cabin, a polog, built inside, that can be kept warm where people sleep.[5]

The Chapline Eskimos (Ungazigmit), Siberian Yupik peoples, also use yarangas for winter. They have a framework made of posts and covered with canvas.[6] The yaranga was surrounded by sod or planking at the lower part. There was a smaller cabin inside it at the backt, used for sleeping and living. It was separated from the outer, cooler parts of the yaranga with haired reindeer skins and grass, supported by a cage-like framework. The household work was done in the main section of the yaranga in front of this inner building, and many household utensils were kept there; during winter storms and at night the dogs were also kept there.[7]

Mongolian gers

The Mongolian roof poles are straight, with separate poles for the walls. A tono or central ring for the roof is carefully crafted by a skilled artisan and very heavy, often requiring supports, bagana.[1]

The doors to the ger are heavy and made of wood. They are considered a symbol of status.[1]

For Mongolians, a ger is not just a shelter it represents their whole world view. The floor is based on the four directions: the door opens to the south; the sacred space is oppposite the door to the north; the western half is the yang or masculine area with men's possessions (hunting and riding gear) and seating for the men; the eastern side is the yin or feminine area for the women and their household equipment. The ger holds the balance and flow of yang and yin, of the worlds above and below, centered around the sacred fire in a circle that balances all aspects of life.[1]

Turkic yurts

The Turkic yurts are constructed from bent poles that serve both as walls and roof. The roof ring is light and simple to make, requiring no additional support.

Turkic yurts may have double doors that open inward, but more commonly the doorways are covered with colorful flaps or felt or rugs. These are artistic creations with beautiful designs appliqued on them.[1]

Western yurts

In the United States and Canada, yurts are made using modern materials. They are highly engineered and built for extreme weather conditions. In addition, erecting one can take days and they are not intended to be moved often. Often the designs of these North American yurts barely resemble the originals; they are better named yurt derivations, because they are no longer round felt homes that are easy to mount, dismount, and transport.

There are three North American variants, the portable fabric yurt, the tapered wall yurt created by Bill Coperthwaite, and the frame panel yurt designed by David Raitt.[1]

North American yurts and yurt derivations were pioneered by William Coperthwaite in the 1960s, after he was inspired to build them by an article about Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas's visit to Mongolia.[8] The photographs of Mongolian gers inspired him and he began designing wooden yurts. Over the years he became involved in hundreds of educational and community projects involving the building of yurts. One of Coperthwaite's students David Raitt, also went on to pursue yurt design and building.[9] Their yurts are made of wood and set on permanent foundations, unlike the original portable structures.

Another of Coperthwaite's students, Chuck Cox, built a canvas-covered yurt as a student project at Cornell University. His subsequent designs became the basis of canvas yurt design that became popular throughout North America.[1] Different groups and individuals use yurts for a variety of purposes, from full-time housing to school rooms, offices, shops, and studios. In some provincial parks in Canada, and state parks in several US states, permanent yurts are available for camping. Yurts have also been used to house migrant workers in Napa Valley, California.

In Europe, a closer approximation to the Mongolian and Central Asian yurt is in production in several countries. These tents use local hardwood, and often are adapted for a wetter climate with steeper roof profiles and waterproof canvas. In essence they are yurts, but some lack the felt cover that is present in traditional yurt.

Notes

- ↑ 1.00 1.01 1.02 1.03 1.04 1.05 1.06 1.07 1.08 1.09 1.10 1.11 Becky Kemery, 2006. Yurts: Living in the Round. Gibbs Smith, Publisher. ISBN 978-1586858919

- ↑ Paul King, 2002

- ↑ World Vision Protection from exposure and cold. Gift Catalog, 2008. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ↑ Countries and Their Cultures, Living Conditions World Cultures: Norway to Russia, 2007. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ↑ Vladimir Dinets, Chukchi art Vladimir Dinets website, 2006. Retrieved November 17, 2008.

- ↑ Рубцова 1954: 515

- ↑ Рубцова 1954: 100–101

- ↑ Becky Kemery, 2001, Yurts - Round and Unbound. Alternatives Magazine 18. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- ↑ David Raitt, History. Vital Designs, 2006. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Kemery, Becky. 2001. Yurts - Round and Unbound. Alternatives Magazine 18. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- Kemery, Becky. 2006. Yurts: Living in the Round. Gibbs Smith, Publisher. ISBN 978-1586858919

- King, Paul. 2002. The Complete Yurt Handbook. Eco-Logic Books. ISBN 1899233083

- Kuehn, Dan Frank. 2006. Mongolian Cloud Houses: How to Make a Yurt and Live Comfortably. Shelter Publications. ISBN 978-0936070391

- Raitt, David. 2006. History. Vital Designs. Retrieved November 16, 2008.

- Рубцова (Rubcova), Е. С. 1954. Материалы по языку и фольклору эскимосов (чаплинский диалект) (Materials on the Language and Folklore of the Eskimos, Vol. I: Chaplino Dialect). Москва: Российская академия наук (Moscow: Russian Academy of Sciences).

External links

- Yurt FAQ

- yurtinfo.org A comprehensive resource for yurts and related structures

- Simply Differently.org Yurt building resources

- Build your own Yurt

- DEC n' NRT Build a YURT

- Kazakh Yurt Set-Up video from Kazakh community in northwestern China.

- Chukchi art

- Winter yaranga in Ungazik village

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.