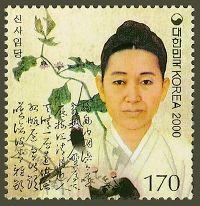

Shin Saimdang

| Shin Saimdang | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Biosite shin.JPG | ||||||||

| Korean name | ||||||||

|

Shin Saimdang (1504-1551) Shin Saimdang was a famous Joseon Dynasty (1392-1910) Korean painter and calligraphist. She was also known as Eojin Eomeoni (어진 어머니; Wise Mother) and for over 500 years has been a model of both excellent mothering skills and filial piety.

Family and Early Years

Sin Saimdang (1504-1551) was born in the village of Pukp’yong, Kangnŭng, Kangwon Province. She was a descendant of the Sin family from P’yŏngsan. The P’yŏngsan Sin clan founder was General Sin Sung-gyeom. Kong Taejo of Goryeo granted Sin Sung-gyeom 300 gyul of land for his hunting skills and the clan name Pyeongsang Sin for his loyalty and bravery in battle.

Saimdang’s father, Sin Myŏnghwa (1476-1522), was a scholar and had earned the Chinsa (presented scholar) title in 1516, but did not serve at the court of King Jungjong because of political conflicts. Saimdang's father taught her the classics and gave her the name Saimdang in honor of Tairen (T’aeim in Korean) the mother of King Wen of China (Western Zhou Dynasty), who was revered as a good mother and good wife. In Lenü zhuan, translated as Biographies of Exemplary Women, the author, Lui Xiang, mentions that Tairen was capable in fetal instruction; meaning that she refused foods that might disturb the fetus, and she was careful not to see or hear disturbing sights or sounds. Tairen also had blind musicians chant odes at night, much like mothers in the twenty first century play Mozart for their fetuses. Like Confucius, Tairen aligned herself with Li Rites as outlined in the Book of Rites. By doing these things Tairen gave birth to healthy children who were gifted; superior in talent and virtue.[1] Tairen was credited with the rise of the Zhou dynasty, because she was the mother of the founder, Wen.)[2]

Saimdang’s mother was from the Yi clan of Yong’in in Kyŏnggi province that developed a base in Kangnŭng. Saimdang’s mother was the only daughter of scholar, Yi Saon. Yi Saon educated Saimdang’s mother in the classics.

Saimdang married Yi Wǒnsu (1501-1562) of the Toksu Yi clan in 1522 at the age of nineteen. Yi Won-su was a descendant of the famous naval Admiral, Yi Sun-shin. The Toksu Yi clan had established their home town in Yul-gok village, P’aju, Kyonggi Province (Yul-gok means Chestnut Valley, and is the pen name chosen by her son, the Confucian scholar, Yi Yi.) Yi Won-su was a scholar and governmental official. The tombs of Saimdang, Yul-gok and several family members are located in the village.

Ojukheon

Saimdang had seven children. She lived with her parents at their Kangwon Province ancestral home, Ojukheon, until the birth of her first son, Yul-gok. Ojukheon was built during King Jungjong’s reign. The house and property was named, Ojukheon, after the back bamboo that grew prolifically upon the grounds. Twenty First Century Ojukheon is a large complex of yangban houses of exquisite architecture, a small park and two museums. Ojukheon was originally owned by Choi Chi Wun (1390-1440) and was bequeathed to his son Eung Hyeon. Yi Saon, inherited the property from Eung Hyeon, his father-in-law. In turn, Yi Saon bequeathed the property to his son-in-law, Shin Myeong Hwa, Saimdang’s father. Saimdang’s father gave the property to his son-in-law Gweon Hwa. When Saimdang’s widowed mother died, she distributed her property to her 5 daughters.

Shin Saimdang's artistic work

Paintings

Although Confucianism had replaced Buddhism during the Choson Dynasty, Buddhist symbolism (like the “Four Gentlemen; bamboo, plum orchid and chrysanthemum),[3] was still popular in art forms. Animals and insects held to a certain order of behavior in nature, just as human relationships did in Confucian Choson society and the paintings attributed to Saimdang reflect the natural affinity and order between insect and plant life.[4]

Saimdang painted landscapes, and garden scenes of insects, vegetation and flowers. She was known for her calligraphic style monochrome grapevine renderings in ink; painted in literati style. These were contemplated in the sarangbang, the study and living quarters of male heads of yangban households.[5]

Saimdang is perhaps best known and loved for the colorful and realistic genre paintings attributed to her. These mimetic paintings, studies of nature scenes most probably from her own gardens, were called Chochoongdo, comprise one form of Min hwa or Korean Folk Painting.[6] Legendary tales arose about realism of Saimdang’s paintings; chickens mistook her painted insects for real ones and pecked holes in one painted screen, only where the insects were painted.[7]

In all, some 40 paintings have been attributed to Saimdang. Proving what Saimdang actually painted is more difficult. Attribution of several paintings may have been given granted to Saimdang in order to help establish political legitimacy for the Neo-Confucian order that her son, Yul-gŏk, initiated. Song Si-yǒl (1607-1689), a disciple of the Yul-gok’s Soin faction, wrote about the painting, Autumn Grasses and Multitude of Butterflies:

“This painting was done by Mr. Yi [Wonsu]”s wife. What is in the painting looks as if created by heaven; no man can surpass [this]. She is fit for being the mother of Master Yul-gŏk."[8]

Song’s main disciple, Kwŏn Sangha, wrote his own colophon in 1718 about a set of four ink paintings (flowers, grasses, fish and bamboo) that he attributed to Saimdang (that are now in the Pang Iryŏng Collection). The variety of technique and style of the later genre paintings attributed to Saimdang can thus be explained. By inference, the mythological proportions of the legends surrounding Saimdang, may have actually originated with Song and Kwon, in order to elevate Yul-gŏk and his philosophy by “creating the myth of an exceptional woman worthy of being his mother.”[9]

Historical records that discuss Saimdang’s paintings are scarce, but two sources remain. Firstly, mention of her work by her son, Yul-gŏk, and his contemporaries. Secondly, the colophons about the paintings that were written later.[10]Yul-gŏk wrote about her in his biographical obituary, Sonbi Haengjang (Biography of My Deceased Mother):

- When she was young, she mastered the classics. She had talent in writing and in the use of the brush. In sewing and embroidery, she displayed exquisite skills…From the age of seven, she painted landscapes after Kyon (active ca. 1440-1470), and also painted ink grapes. There were so wondrous that no one could dare imitate them. Screens and scrolls [she painted] are around today.[11]

O Sukkwon (court translator and author of the P’aegwan Chapgi, wrote of her paintings: “Today there is Madam Sin of Tongyang, who excelled in painting since her childhood. Her paintings of landscapes and grapes are so excellent that people say there come only next to those by An Kyon. How can one belittle her paintings just because they were done by a woman, and how can we scold her for doing what a woman is not supposed to do?”[12] Unlike many artists, Saimdang was famous in her own time. Her painting,” Autumn Grass,” was so popular that it was used as a pattern for court ceramics.[13]

Embroidery

Embroidery was a popular art form in Choson Korea. All items of wearing apparel were embroidered, even table coverings. Pojagi, cloths used by both yangban and peasant women for wrapping and carrying items, were also embroidered; as were silk screens. Yi Sŏng-Mi, suggests an embroidered screen in Tong’a University Museum in Pusan, South Kyŏngsang Province may have been done by Saimdang.[14]

Poetry

Saimdang transcribed poems into calligraphic Hanja art forms and wrote her own poetry. Two of her poems are left to us and are about her parents. "Yu Daegwallyeong Mangchin Jeong"(Looking Homeward From a Mountain Pass) and "Sajin"(Yearning for Parents). [15] Daegwallyeong Pass along the old Daegwallyeong Road is mentioned in the first poem.[16]

- Looking Homeward From a Mountain Pass

- Leaving my old mother in the seaside town,

- Alas! I am going alone up to Seoul,

- As I turn, once in a while, to look homeward on my way,

- White clouds rush down the darkening blue mountains.[17]

Calligraphy

Very few examples of Saimdang’s calligraphy remain. The most significant is a large paneled screen, a Gangwon Province Tangible Cultural Property. Transcribed poems from the Tang dynasty are written in quatrains with 5 Chinese characters to each line, in cursive style. The screen was given to the son of Saimdang’s fourth sister, Gwon Cheongyun. One of his daughters inherited it upon her marriage to Ghoe Daehae and remained in the family for generations. It was donated to Ganneung City in 1972 and is currently on display at Ojukheon Museum.[18]

Legacy

Saimdang’s artistic legacy extended to 3 generations. Her first daughter, Maech’ang, was known for her paintings of bamboo and plum in ink. Her youngest son, Oksan Yi Wu (1542-1609), was a talented musician, poet, calligrapher and painter who specialized in painting the four gentlemen (bamboo, plum, orchid and chrysanthemum), and grapes in ink. Oksan’s daughter, Lady Yi (1504-1609), was recognized for her ink bamboo paintings.

Siamdang's intellectual and moral legacy has survived more than 500 years and is immeasurable. Just as Tairen was credited with the rise of the Zhou dynasty because she mothered its founder, Wen,

Saimdang can be given credit for the rise of the Kiho hakp'a tradition of Confucianism, because she mothered Yul-gŏk. Yul-gŏk became an eminent Confucian scholar and held royal appointments as minister of war and rector of the national academy. (Tairen is hailed as one of the ancient practioners of tai jiao, instruction of the embryo.) [20] Fetal Education was an act of filial piety toward Heaven.

Even with the introduction of Christian equality before Father God, Confucian ideals permeate Twenty-first century Korean society. Ancestor worship, respect for elders, filial piety; arranged marriages and the subordination of women are still Korean cultural norms. Saimdang, who lived in a much more restrictive environment, managed to become so successful that her name is legendary some 500 years later. How did Saimdang fulfill the pharisaic and scribian rules that Confucian society metted out to women and still become successful as an artist?

Siamdang lived in her parents home, performing the duties of an absent son. When her husband took a mistress/concubine, she went to Mt. Kumgang to meditate.

The thinker who stressed the primacy of Li was ToeGye (1501 1570), and the one who gave emphasis to Ki was YulGok(1536 1584). They became a foundation for much of later Korean idealism and empiricism. [22]

Gallery

See also

- List of Korea-related topics

- History of Korea

- Korean painting

Notes

- ↑ Anne Behnke Kinney. Representations of Childhood and Youth in Early China (Stanford University Press, 2004, ISBN 9780804747318),165

- ↑ Susan Mann, Yi Yin Ching; editors. Under Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 9780520222762),66

- ↑ The Metropolitan Museum of Art © 2000-2007 http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ho/08/eak/hod_1994.439.htm

- ↑ Saehyang P. Chung,Turning Toward Each Other: Warmth and Intimacy In Chosŏn-Dynasty Animal Paintings (Pohang University of Science and Technology.)[1]

- ↑ Chung

- ↑ http://park.org/Korea/Pavilions/PublicPavilions/KoreaImage/e-information/culture/tra-003.html

- ↑ Jung Yeon Ma, The Virtuality and Reality of Augmented RealityDept of Image Engineering, GSAIM, Chungang University, Seoul, Korea. [2]

- ↑ Yi Sŏng-Mi. Sin Saimdang: The Foremost Woman Painter of the Chosŏn Dynasty. Creative Women Of Korea. The Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Centuries, edited by Young-Key Kim-Reynaud, (Armonk & London: M.E. Sharpe, 2004. ISBN 9780765611888)72,

- ↑ Yi Sŏng-Mi,70-73

- ↑ Yi Sŏng-Mi,60

- ↑ Yi Sŏng-Mi,60

- ↑ Ibid pg 60-61

- ↑ Tongil Korea http://www.tongilkorea.net/?action=fullnews&showcomments=1&id=4785

- ↑ Yi Sŏng-Mi. Sin Saimdang: The Foremost Woman Painter of the Chosŏn Dynasty. Creative Women Of Korea. The Fifteenth Through the Twentieth Centuries, edited by Young-Key Kim-Reynaud, (Armonk & London: M.E. Sharpe, 2004, ISBN 9780765611888),61

- ↑ http://world.kbs.co.kr/english/news/news_newissue_detail.htm?No=145

- ↑ The Old Road of Daegwallyeong http://www.gntour.go.kr/CMSViewContent.do?pid=1221&print=1

- ↑ Peter H. Lee. The Columbia anthology of traditional Korean poetry. Translations from the Asian classics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2002, ISBN 9780231111133.

- ↑ http://www.gntour.go.kr/english/CMSView.do?pid=1147&cpage=1

- ↑ Susan Mann, Yi Yin Ching; editors. "Under Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History" (University of California Press) pg 66 ISBN 0620-22276-8

- ↑ David R.Knechtges 2002. Court culture and literature in early China. Variorum collected studies series. (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2002, ISBN 9780860788843)

- ↑ Stuart J. Foster, Keith A. Crawford, "What do we tell the children? National Perspective on school History Textbooks", (South Korea text books. In his Sunbihangjang, yulgok wrote about his mohter; "she was not eager to educate her children or support her husband, but she was not a bad mother.”

- ↑ [3]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Kinney, Anne Behnke . Representations of Childhood and Youth in Early China. Stanford University Press, 2004, ISBN 9780804747318

- Mann, Susan & Yi Yin Ching; editors. Under Confucian Eyes: Writings on Gender in Chinese History , Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2001, ISBN 9780520222762

External Links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.