Difference between revisions of "Sea turtle" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 33: | Line 33: | ||

Extant sea turtles are placed into two families within the superfamily Chelonioidea. | Extant sea turtles are placed into two families within the superfamily Chelonioidea. | ||

| − | '''Cheloniidae''' includes six species in five genera: [[Flatback Sea Turtle|flatback]] ''(Natator depressus)'', [[Green Sea Turtle|green sea turtle]] ''(Chelonia mydas)'', [[Hawksbill turtle|hawksbill]] ''( Eretmochelys imbricata)'', [[Kemp's Ridley]] ''((Lepidochelys kempii))'', [[Olive Ridley Sea Turtle|olive Ridley]] ''(Lepidochelys olivacea)'', and [[Loggerhead Sea Turtle|loggerhead]] ''(Caretta caretta)''. The East Pacific subpopulation of the green turtle was previously classified as a separate [[species]], the [[Black Sea Turtle|black turtle]], but [[DNA]] evidence indicates that it is not sufficiently distinct from the [[green turtle]] (Karl and Bowen 1999). These species are all characterized by a streamlined shell that is low and covered with scutes | + | '''Cheloniidae''' includes six species in five genera: [[Flatback Sea Turtle|flatback]] ''(Natator depressus)'', [[Green Sea Turtle|green sea turtle]] ''(Chelonia mydas)'', [[Hawksbill turtle|hawksbill]] ''( Eretmochelys imbricata)'', [[Kemp's Ridley]] ''((Lepidochelys kempii))'', [[Olive Ridley Sea Turtle|olive Ridley]] ''(Lepidochelys olivacea)'', and [[Loggerhead Sea Turtle|loggerhead]] ''(Caretta caretta)''. The East Pacific subpopulation of the green turtle was previously classified as a separate [[species]], the [[Black Sea Turtle|black turtle]], but [[DNA]] evidence indicates that it is not sufficiently distinct from the [[green turtle]] (Karl and Bowen 1999). These species are all characterized by a streamlined shell that is low and covered with scutes (external plates derived from the epidermis), paddle-like forelimbs, a large head that cannot be retracted into the shell, and a skull with a solid, bony roof (Iverson 2004a). Different species are distinguished by varying anatomical aspects: for instance, the prefrontal scales on the head, the number of and shape of [[scutes]] on the [[carapace]], and the type of inframarginal scutes on the [[plastron]]. Species generally range from two to four feet in length (0.5 to 1 meters) and proportionally narrower (WWF 2009). |

| − | '''Dermochelyidae''' includes one extant species, the leatherback sea turtle (''Dermochelys coriacea''). The [[leatherback sea turtle|leatherback]] is the only sea turtle that does not have a hard shell, instead carrying a mosaic of hundreds of bony plates just beneath its leathery skin. It is characterized by a smooth, streamlined carapace that is teardrop shaped, seven longitudinal ridges, no epidermal scutes, no scales on the head, and a prominent tooth-like cusp on both sides of the upper jaw (Iverson 2004b). The paddle-like forearms lack claws (Iverson 2004b). The leatherback is the largest of the sea turtles, measuring six or seven feet (2 meters) in length at maturity, and three to five feet (1 to 1.5 m) in width, weighing up to 1300 pounds (650 kg). | + | '''Dermochelyidae''' includes one extant species, the leatherback sea turtle (''Dermochelys coriacea''). The [[leatherback sea turtle|leatherback]] is the only sea turtle that does not have a hard shell, instead carrying a mosaic of hundreds of bony plates just beneath its leathery skin. It also is characterized by a smooth, streamlined carapace that is teardrop shaped, seven longitudinal ridges, no epidermal scutes, no scales on the head, and a prominent tooth-like cusp on both sides of the upper jaw (Iverson 2004b). The paddle-like forearms lack claws (Iverson 2004b). The leatherback is the largest of the sea turtles, measuring six or seven feet (2 meters) in length at maturity, and three to five feet (1 to 1.5 m) in width, weighing up to 1300 pounds (650 kg). |

[[Image:Chelonia mydas got to the surface to breath.jpg|250px|thumb|left|Green turtle breaks the surface to breathe.]] | [[Image:Chelonia mydas got to the surface to breath.jpg|250px|thumb|left|Green turtle breaks the surface to breathe.]] | ||

| Line 42: | Line 42: | ||

Sea turtles possess a salt excretory gland at the corner of the eye, in the nostrils, or in the tongue, depending upon the species; chelonian salt glands are oriented in the corner of the eyes in leatherback turtles. Due to the iso-osmotic makeup of jellyfish and other gelatinous prey upon which sea turtles subsist, sea turtle diets are high in salt concentrations and chelonian salt gland excretions are almost entirely composed of sodium chloride at approximately 1500-1800 mosmoll-1 (Marshall and Cooper 1988; Nicolson and Lutz 1989; Reina and Cooper 2000). | Sea turtles possess a salt excretory gland at the corner of the eye, in the nostrils, or in the tongue, depending upon the species; chelonian salt glands are oriented in the corner of the eyes in leatherback turtles. Due to the iso-osmotic makeup of jellyfish and other gelatinous prey upon which sea turtles subsist, sea turtle diets are high in salt concentrations and chelonian salt gland excretions are almost entirely composed of sodium chloride at approximately 1500-1800 mosmoll-1 (Marshall and Cooper 1988; Nicolson and Lutz 1989; Reina and Cooper 2000). | ||

| − | + | Turtles can rest or sleep underwater for several hours at a time but submergence time is much shorter while diving for food or to escape predators. Breath-holding ability is affected by activity and stress, which is why turtles drown in shrimp trawls and other fishing gear within a relatively short time (MarineBio). | |

| − | |||

| − | Turtles can rest or sleep underwater for several hours at a time but submergence time is much shorter while diving for food or to escape predators. Breath-holding ability is affected by activity and stress, which is why turtles drown in shrimp trawls and other fishing gear within a relatively short time | ||

| − | |||

==Distribution== | ==Distribution== | ||

| Line 183: | Line 180: | ||

Richard D. Reina1,*, T. Todd Jones2 and James R. Spotila | Richard D. Reina1,*, T. Todd Jones2 and James R. Spotila | ||

The Journal of Experimental Biology 205, 1853-1860 (2002) | The Journal of Experimental Biology 205, 1853-1860 (2002) | ||

| + | |||

| + | <ref name="MarBioCmydas">{{cite web | title =Green Sea Turtle | publisher =MarineBio.org | date =[[2007-05-21]] | url =http://marinebio.org/species.asp?id=51 Chelonia mydas | ||

| + | Green Sea Turtle. n.d. | accessdate = 2008-10-09 }}</ref> | ||

Marshall, A. T. and Cooper, P. D. (1988). Secretory capacity of the lachrymal salt gland of hatchling sea turtles, Chelonia mydas. J. Comp. Physiol. B 157,821 -827. | Marshall, A. T. and Cooper, P. D. (1988). Secretory capacity of the lachrymal salt gland of hatchling sea turtles, Chelonia mydas. J. Comp. Physiol. B 157,821 -827. | ||

Revision as of 23:16, 20 January 2009

| Sea Turtle | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hawaiian green sea turtle

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

|

Sea turtle (or seaturtle) is the common name for any of the large marine turtles comprising the superfamily Chelonioidea, characterized by forelimbs in the form of large flippers or paddles. There are two extant families, Cheloniidae and Dermochelyidae. Members of the family Cheloniidae are characterized by a lightweight, low shell covered with scutes, while the sole extant species in Dermochelyidae, the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea), is characterized by a teardrop shaped carapace lacking epidermal shutes and covered with a leathery skin. Members of both families have a large head that cannot be retracted into the shells. There are seven living species, arranged into six genera. Three extinct genera also are recognized. Sea turtles are found in all the world's oceans except the Arctic Ocean.

Overview and description

Although sea turtles have been around for tens of millions of years since the Mesozoic, the body plan of sea turtles has remained relatively constant. Sea turtles possess dorsoventrally-flattened bodies with two hind legs and highly-evolved paddle-like front arms (Lutz and Musick 1996).

Extant sea turtles are placed into two families within the superfamily Chelonioidea.

Cheloniidae includes six species in five genera: flatback (Natator depressus), green sea turtle (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill ( Eretmochelys imbricata), Kemp's Ridley ((Lepidochelys kempii)), olive Ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), and loggerhead (Caretta caretta). The East Pacific subpopulation of the green turtle was previously classified as a separate species, the black turtle, but DNA evidence indicates that it is not sufficiently distinct from the green turtle (Karl and Bowen 1999). These species are all characterized by a streamlined shell that is low and covered with scutes (external plates derived from the epidermis), paddle-like forelimbs, a large head that cannot be retracted into the shell, and a skull with a solid, bony roof (Iverson 2004a). Different species are distinguished by varying anatomical aspects: for instance, the prefrontal scales on the head, the number of and shape of scutes on the carapace, and the type of inframarginal scutes on the plastron. Species generally range from two to four feet in length (0.5 to 1 meters) and proportionally narrower (WWF 2009).

Dermochelyidae includes one extant species, the leatherback sea turtle (Dermochelys coriacea). The leatherback is the only sea turtle that does not have a hard shell, instead carrying a mosaic of hundreds of bony plates just beneath its leathery skin. It also is characterized by a smooth, streamlined carapace that is teardrop shaped, seven longitudinal ridges, no epidermal scutes, no scales on the head, and a prominent tooth-like cusp on both sides of the upper jaw (Iverson 2004b). The paddle-like forearms lack claws (Iverson 2004b). The leatherback is the largest of the sea turtles, measuring six or seven feet (2 meters) in length at maturity, and three to five feet (1 to 1.5 m) in width, weighing up to 1300 pounds (650 kg).

Sea turtles spend almost all their lives submerged but must breathe air for the oxygen needed to meet the demands of vigorous activity. With a single explosive exhalation and rapid inhalation, sea turtles can quickly replace the air in their lungs. The lungs are adapted to permit a rapid exchange of oxygen and to prevent gasses from being trapped during deep dives. The blood of sea turtles can deliver oxygen efficiently to body tissues even at the pressures encountered during diving. During routine activity, green and loggerhead turtles dive for about 4 to 5 minutes and surface to breathe for 1 to 3 seconds.

Sea turtles possess a salt excretory gland at the corner of the eye, in the nostrils, or in the tongue, depending upon the species; chelonian salt glands are oriented in the corner of the eyes in leatherback turtles. Due to the iso-osmotic makeup of jellyfish and other gelatinous prey upon which sea turtles subsist, sea turtle diets are high in salt concentrations and chelonian salt gland excretions are almost entirely composed of sodium chloride at approximately 1500-1800 mosmoll-1 (Marshall and Cooper 1988; Nicolson and Lutz 1989; Reina and Cooper 2000).

Turtles can rest or sleep underwater for several hours at a time but submergence time is much shorter while diving for food or to escape predators. Breath-holding ability is affected by activity and stress, which is why turtles drown in shrimp trawls and other fishing gear within a relatively short time (MarineBio).

Distribution

The superfamily Chelonioidea has a worldwide distribution; sea turtles can be found in all oceans except for in the polar regions.[citation needed] Some species travel between oceans. The Flatback turtle is found solely on the northern coast of Australia.

Ecology and life history

Sea turtles are highly sensitive to the Earth's magnetic field and use it to navigate. The longevity of sea turtles has been speculated at 80 years. The fact that most species return to nest at the locations where they were born seems to indicate an imprint of that location's magnetic features. The Ridley turtles are especially peculiar because instead of nesting individually like the other species, they come ashore in one mass arrival known as an "arribada" (arrival). With the Kemp's Ridley this occurs during the day. Their numbers used to range in the thousands but due to the effects of extensive egg poaching and hunting in previous years the numbers are now in the hundreds.

After about 30 years of maturing, adult female sea turtles return to the land to nest at night, usually on the same beach from which they hatched. This can take place every two to four years in maturity. They make from four to seven nests per nesting season.

All sea turtles generally employ the same methods when making a nest. A mature nesting female hauls herself onto the beach until she finds suitable sand on which to create a nest. Using her hind flippers, the female proceeds to dig a circular hole 40 to 50 centimeters deep. After the hole is dug, the female then starts filling the nest with a clutch of soft-shelled eggs one by one until she has deposited around 150 to 200 eggs, depending on the turtle's species. The nest is then re-filled with loose sand by the female, re-sculpting and smoothing the sand over the nest until it is relatively undetectable visually. The whole process takes around thirty minutes to a little over an hour. After the nest is laid, the female then returns to the ocean.[1]

Some of the eggs are unfertilized and the rest contain young turtles. Incubation takes about two months. The length of incubation and the gender of the hatchling depends on the temperature of the sand. Darker sands maintain higher temperatures, decreasing incubation time and increasing the frequency of female hatchlings. When the time comes, these hatchlings tear their way out of their shells with their snout and once they have reached the surface of the sand, they will instinctively head towards the sea. Only a very small proportion of them (usually .01%) will be successful, as many predators wait to eat the steady stream of new hatched turtles (since many sea turtles lay eggs en masse, the eggs also hatch en masse).[citation needed]

The hatchlings then proceed into the open ocean, borne on oceanic currents that they often have no control over. While in the open ocean, it used to be the case that what happened to sea turtle young during this stage in their lives was unknown. However in 1987, it was discovered that the young of Chelonia mydas and Caretta caretta spent a great deal of their pelagic lives in floating sargassum beds - thick mats of unanchored seaweed floating in the middle of the ocean. Within these beds, they found ample shelter and food. In the absence of sargassum beds, turtle young feed in the vicinity of upwelling "fronts".[2] In 2007, it was verified that green turtle hatchlings spend the first three to five years of their lives in pelagic waters. Out in the open ocean, pre-juveniles of this particular species were found to feed on zooplankton and smaller nekton before they are recruited into inshore seagrass meadows as obligate herbivores.[3][4]

Instinctive protections

Like many other animals in the world, sea turtles have predators. An example of natural protection is their shell. Other protections include the ability of some species' massive jaws to suddenly snap shut, and to stay underwater for hours on end; these are both instinctual and natural. Turtles have many senses to aid them in the sea. Sea turtle ears have a single bone in the middle ear that conducts vibrations to the inner ear. Researchers have found that sea turtles respond to low frequency sounds and vibrations. Sea turtles have an extremely good eyesight in water but are shortsighted on land. Under experimental conditions, the loggerhead and green sea turtle hatchlings showed a preference for ultraviolet, blue-green and violet light. Sea turtles are touch-sensitive on the soft parts of their flippers and on their shell. Most researchers' theories portray that sea turtles have an acute sense of smell in the water. Their experiments showed that the hatchlings reacted to the scent of shrimp. This sense allows sea turtles to locate food in deep and murky water. Sea turtles open their mouths a bit and draw in water through the nose, then immediately empty it out again through the mouth. Pulsating movements of the throat are thought to be associated with smelling. Sea turtles have very hard shells. Sea turtles are many different colors like blue green and light violet. Sea turtles flippers are very soft and sensitive.

Importance to humans

Marine turtles are caught worldwide, despite it being illegal to hunt most of the species in many countries.[5][6]

A great deal of intentional marine turtle harvests worldwide are for the food industry. In many parts of the world, the flesh of sea turtles are considered fine dining. Texts dating back to the fifth century B.C.E. describes sea turtles as exotic delicacies in ancient China.[7] Historically, many coastal communities around the world have depended on sea turtles as a source of protein. Several turtles could be harvested at once and kept alive on their backs for months until needed. The skin of the flippers are also prized for use as shoes and assorted leather-goods.

To a much lesser extent, specific species of marine turtles are targeted not for their flesh, but for their shells. Tortoiseshell, a traditional decorative ornamental material used in Japan and China, is derived from the carapace scutes of the hawksbill turtle.[8][9] The use of marine turtle shells for decorative purposes is by no means limited to the orient. Since ancient times, the shells of sea turtles (primarily the hawksbill) have been used by the ancient Greeks and ancient Romans. Various articles and ornaments used by the elite of these societies, such as combs and brushes, were from processed turtle scutes.[10] The Moche people of ancient Peru worshipped the sea and its animals. They often depicted sea turtles in their art.[11]

Conservation

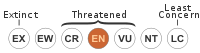

All species of sea turtles are listed as threatened or endangered. The leatherback, Kemp's ridley, and hawksbill turtles are listed as critically endangered. The olive ridley and green turtles are considered endangered, and the loggerhead is a threatened species.[12] The flatback's conservation status is unclear due to a lack of research data.

Sea turtles used to be hunted on a large scale in the whaling days for their meat, fat and shells. Coastal peoples have also been known to gather turtle eggs for consumption.[13] One of their most significant threats now comes from bycatch due to various fishing methods, long-line fishing has been blamed as one of the causes of accidental sea turtle deaths,[14] and the black market demand for tortoiseshell for both decoration and supposed health benefits.[15]

Nets used in shrimp trawling and fishing have been known to cause the accidental deaths of sea turtles. The turtles, as air-breathing reptiles, must surface to breathe. Caught in a fisherman's net, they are unable to go to the surface to breathe and suffocate to death in the net. In early 2007, almost a thousand sea turtles were killed inadvertently in the Bay of Bengal over the course of a few months as a result of becoming trapped in fishing nets.[16]

However some relatively inexpensive changes to fishing techniques, such as slightly larger hooks and traps from which sea turtles can escape, can dramatically cut the mortality rate.[17] Turtle Excluder Devices (TEDS) have reduced sea turtle bycatch in shrimp nets by 97 percent. Another danger comes from marine debris, especially from abandoned fishing nets in which they can become entangled.

Beach development is another area which poses threats to sea turtles. Since sea turtles return to the same beach locations to nest, if these areas are developed they may be left with nowhere to nest, or their nesting locations may be threatened by human activity. Therefore, there has been a movement to protect these areas, in some cases by special police. In some areas, such as the east coast of Florida, after the adult turtles lay their eggs, they are dug up and relocated to special fenced nurseries where they can be protected from beach traffic. This is not the best thing to do, as many turtle species return to the beach on which they were born. Hatchlings find their way to the ocean by crawling towards the brightest horizon, but often become disoriented on developed stretches of coastline. Special lighting ordinances may also be enforced to prevent lights from shining on the beach and confusing young hatchlings, causing them to crawl towards the light and away from the water, usually crossing a road. A turtle-safe lighting system uses red light in place of white light as sea turtles can't see red light.

Another major threat to sea turtles is the black market trade in eggs and meat. This is a pervasive problem throughout the world, but especially a concern in the Philippines, India, Indonesia and throughout the coastal nations of Latin America. Estimates are as high as 35,000 turtles killed a year in Mexico and the same number in Nicaragua. Conservationists in Mexico and the United States have launched "Don't Eat Sea Turtle" campaigns in order to reduce the urban black market trade in sea turtle products. These campaigns have involved figures such as Pope John Paul II, Dorismar, Los Tigres del Norte and Mana. Sea turtles are often consumed during the Catholic holiday, Lent, even though they are reptiles, not fish. Conservation organizations have written letters to the Pope asking that he declare turtles meat.

Moreover, global warming may also cause a threat to sea turtles. Since temperatures in the sands define the sex of the turtle while developing in the egg, many feared rising temperatures would only produce one sex, but more research remains to be done in order to understand how climate change might affect sea turtle gender distribution.

Sea turtles can also be affected by Fibropapillomatosis, a disease that has been found amongst sea turtle populations and causes tumors.

Injured sea turtles are sometimes able to be rescued and rehabilitated by professional organizations such as the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota, Florida, the Marine Mammal Center in Northern California, and the ClearWater Marine Aquarium in Clearwater Florida.[18] and the Sea Turtle Inc. organization in South Padre Island, TX.[19] One such turtle, named Nickel for the coin that was found lodged in her throat, lives at the Shedd Aquarium in Chicago.

In the Caribbean, reserchers are having some success in assisting a comeback.[20]

On September 2007, Corpus Christi, Texas wildlife officials found a record of 128 Kemp's ridley sea turtle nests on Texas beaches, including 81 on North Padre Island (Padre Island National Seashore) and 4 on Mustang Island. Wildlife officials released 10,594 Kemp's ridleys hatchlings along the Texas coast this year. The turtles are endangered due to shrimpers' nets and they are popular in Mexico as boot material and food.[21]

In 2007, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and the National Marine Fisheries Service finished a joint study assessing the worldwide populations of all sea turtle species. It was determined that the leatherback, the hawksbill and the Kemp's Ridley populations were endangered while that of green turtles and olive ridleys were threatened.[22]

In Southeast Asia, the Philippines has had several initiatives dealing with the issue of turtle conservation. In 2007, the province of Batangas in the Philippines declared the catching and eating of Pawikans illegal. However, the law seems to have little effect as Pawikan eggs are still in demand in Batangan markets. Today, one can easily purchase three Pawikan eggs for a mere PhP20.[citation needed] On January 23, 2008, the Coastal Resource Management Coordinator arrested and detained fisherman Israel Jimenez, 40, from Poblacion, Bacuag, Surigao del Norte who slaughtered an endangered sea turtle, pending the filing of case by the Bureau of Fisheries and Aquatic Resources.[23]

In September 2007, several Chinese poachers were apprehended off the Turtle Islands in the country's southernmost province of Tawi-Tawi. The poachers were discovered to have collected more than a hundred sea turtles, along with 10,000 turtle eggs.[24]

Fragile ecosystems

Sea turtles play key roles in two ecosystems that are critical to them as well as to humans—the oceans and beaches/dunes. If sea turtles were to become extinct, the negative impact on beaches and the oceans would potentially be significant.

In the oceans, for example, sea turtles, especially green sea turtles, are one of the very few creatures (manatees are another) that eat a type of vegetation called sea grass that grows on the sea floor. Sea grass must be kept short to remain healthy, and beds of healthy sea grass are essential breeding and development areas for many species of fish and other marine life. A decline or loss of sea grass beds would mean a loss of the marine species that directly depend on the beds, which would trigger a chain reaction and negatively impact marine and human life. When one part of an ecosystem is destroyed, the other parts will follow.

Beaches and dunes are a fragile ecosystem that does not get many nutrients to support its vegetation, which is needed to help prevent erosion. Sea turtles contribute nutrients to dune vegetation from their eggs. Every year, sea turtles lay countless numbers of eggs in beaches during nesting season. Along one twenty-mile (32 km) stretch of beach in Florida alone, for example, more than 150,000 pounds of eggs are laid each year. Nutrients from hatched eggs as well as from eggs that never hatch and from hatchlings that fail to make it into the ocean are all sources of nutrients for dune vegetation. A decline in the number of sea turtles means fewer eggs laid, less nutrients for the sand dunes and its vegetation, and a higher risk for beach erosion.

Taxonomy and classification

Sea turtles, along with other turtles and tortoises, are part of the Order Testudines.

Seven distinct species of sea turtles grace our oceans today; they constitute a single radiation that was distinct from all other turtles at least 110 million years ago. During that radiation, sea turtles split into two main subgroups, which still exist today: the unique family Dermochelyidae, which consists of a single species, the leatherback; and the six species of hard-shelled sea turtle, in the family Cheloniidae. From SWOT Report, vol. 1.

- Family Cheloniidae

- Chelonia mydas

- Eretmochelys imbricata

- Natator depressus

- Caretta caretta

- Lepidochelys kempii

- Lepidochelys olivacea

- Family Dermochelyidae

- Dermochelys coriacea

Additional reading

- Davidson, Osha Gray. (2001.) "Fire in the Turtle House: The Green Sea Turtle and the Fate of the Ocean." United States: United States of Public Affairs. ISBN 1-5864-8199-1.

- Sizemore, Evelyn (2002). The Turtle Lady: Ila Fox Loetscher of South Padre. Plano, Texas: Republic of Texas Press, 220. ISBN 1556228961.

- Spotila, James R. (2004). "Sea Turtles: A Complete Guide to Their Biology, Behavior, and Conservation." Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8007-6.

- Witherington, Blair E. (2006). “Sea Turtles: An Extraordinary Natural History of Some Uncommon Turtles.” St. Paul: Voyageur Press. ISBN 0-7603-2644-4.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Iverson, J. B. 2004. Cheloniidae. In

- Iverson, J. B. 2004. Dermochelyidae. In

.[26]

.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag

Marshall, A. T. and Cooper, P. D. (1988). Secretory capacity of the lachrymal salt gland of hatchling sea turtles, Chelonia mydas. J. Comp. Physiol. B 157,821 -827. Nicolson, S. W. and Lutz, P. L. (1989). Salt gland function in the green sea turtle Chelonia mydas. J. Exp. Biol. 144,171 -184 Reina, R. D. and Cooper, P. D. (2000). Control of salt gland activity in the hatchling green sea turtle, Chelonia mydas.J. Comp. Physiol. B 170,27 -35

External links

- SWOT - The State of the World's Sea Turtles - up-to-date information on global sea turtle populations

- Oceana - scientists are tracking turtles in the Mediterranean and the Atlantic to find out more about their habits in the deep sea

- Conserving Turtles on a Global Scale

- - Save the Turtles - Non-profit organization protecting endangered sea turtles by supporting community-based conservation projects and developing international education programs. Teachers around the world invited to participate in collaborative conservation project: [*- Ride the Turtle Education Rainbow

- Underwater video of turtles in the Red Sea, Egypt

- Preserving Turtles

- Seaturtle.org - dedicated to providing online resources and solutions in support of sea turtle conservation and research

- EuroTurtle - European sea turtle conservation and education

- ASUPMATOMA - dedicated to providing public education and awareness about the endangered sea turtles and environmental issues impacting Southern Baja California, Mexico

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.

- ↑ Audubon, Maria R. (1897/1986). Audubon and His Journals: Dover Publications Reprint. New York: Scribner's Sons, 373–375. ISBN 978-0486251448.

- ↑ Carr, Archie (August 1987). New Perspectives on the Pelagic Stage of Sea Turtle Development. Conservation Biology 1 (2): 103–121.

- ↑ Reich, Kimberly J. and Karen A. Bjorndal & Alan B. Bolten (2007-09-18). The ‘lost years’ of green turtles: using stable isotopes to study cryptic lifestages. Biology Letters 6 (in press): 712.

- ↑ Brynner, Jeanna, "Sea Turtles' Mystery Hideout Revealed", LiveScience, Imaginova Corp., 2007-09-19. Retrieved 2007-09-20. (written in English)

- ↑ CITES (2006-06-14). Appendices (SHTML). Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Flora and Fauna. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ↑ UNEP-WCMC. Eretmochelys imbricata. UNEP-WCMC Species Database: CITES-Listed Species. United Nations Environment Programme - World Conservation Monitoring Centre. Retrieved 2007-02-05.

- ↑ Schafer, Edward H. (1962). Eating Turtles in Ancient China. Journal of the American Oriental Society 82 (1): 73–74.

- ↑ Heppel, Selina S. and Larry B. Crowder (June 1996). Analysis of a Fisheries Model for Harvest of Hawksbill Sea Turtles (Eretmochelys imbricata). Conservation Biology 10 (3): 874–880.

- ↑ Strieker, Gary, "Tortoiseshell ban threatens Japanese tradition", CNN.com/sci-tech, Cable News Network LP, LLLP., 2001-04-10. Retrieved 2007-03-02. (written in english)

- ↑ Casson, Lionel (1982). Periplus Maris Erythraei: Notes on the Text. The Journal of Hellenic Studies 102: 204–206.

- ↑ Berrin, Katherine & Larco Museum. The Spirit of Ancient Peru:Treasures from the Museo Arqueológico Rafael Larco Herrera. New York: Thames and Hudson, 1997.

- ↑ US Fish and Wildlife Services. "Species Profile: Loggerhead sea turtle." 2007. February 22, 2007. [1]

- ↑ Sam Settle, 1995. Marine Turtle Newsletter 68:8-13 [2]

- ↑ Smith, Tim, "Turtles and birdlife at risk from long-line fishing, claim campaigners", News, The Royal Gazette Ltd., 2007-02-03. Retrieved 2007-02-06. (written in english)

- ↑ Atlantic Hawksbill Sea Turtle Fact Sheet. Endangered Species Unit. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

- ↑ "Fishermen blamed for turtle deaths in Bay of Bengal", Yahoo! Science News, Yahoo! Inc., 2007-02-05. Retrieved 2007-02-06. (written in english)

- ↑ Irene Kinan . 2006. Marine Turtle Newsletter 113:13-14 [3]

- ↑ The Marine Mammal Center . "Volunteer Opportunities." 2007. February 22, 2007.[4]

- ↑ Sea Turtle, Inc[5]

- ↑ Clarren, Rebecca, "Night Life", Nature Conservancy 58 (4): 32-43

- ↑ Yahoo.com, Endangered turtle nests found in Texas

- ↑ "Sea turtles still endangered, threatened", Yahoo! News, Yahoo! Inc., 2007-09-08. Retrieved 2007-09-07. (written in English)

- ↑ Abs-Cbn Interactive, Sea turtle killer falls

- ↑ Adraneda, Katherine, "WWF urges RP to pursue case vs turtle poachers", Headlines, The Philippine Star, 2007-09-12. Retrieved 2007-09-12. (written in English)

- ↑ Karl, Stephen H. and Brian W. Bowen (1999). Evolutionary Significant Units versus Geopolitical Taxonomy: Molecular Systematics of an Endangered Sea Turtle (genus Chelonia). Conservation Biology 13 (5): 990–999.

- ↑ Lutz, Peter L. and John A. Musick (1996). The Biology of Sea Turtles. CRC PRess, 432pp.. ISBN 0849384222.