Difference between revisions of "Rotifer" - New World Encyclopedia

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

Rick Swarts (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 50: | Line 50: | ||

==Taxonomy== | ==Taxonomy== | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | Rotifers are typically divided into three classes, Monogononta, Bdelloidea, and Seisonidea, although Acanthocephala | ||

| + | (spiny-headed worms, thorny-headed worms) are sometimes placed with Rotifera as well (. '''Monogononta''' has about 1,500 species, '''Bdelloidea''' has about 350 species comprising four families and 19 [[genus|genera]], and '''Seisonidea''' has two known species (Baqai et al. 2000, Meselson 2007)). Bdelloid rotifers are small, freshwater invertebrates. | ||

| + | |||

There are about 2000 [[species]], divided into two [[class (biology)|class]]es. The parasitic [[Acanthocephala]] may belong among the rotifers as well. These phyla belong in a group called the [[Platyzoa]]. | There are about 2000 [[species]], divided into two [[class (biology)|class]]es. The parasitic [[Acanthocephala]] may belong among the rotifers as well. These phyla belong in a group called the [[Platyzoa]]. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | |||

| + | *Habrotrochidae | ||

| + | Habrotrocha | ||

| + | Otostephanos | ||

| + | Scepanotrocha | ||

| + | *Philodinavidae | ||

| + | Abrochtha | ||

| + | Henoceros | ||

| + | Philodinavus | ||

| + | *Philodinidae | ||

| + | Anomopus | ||

| + | Ceratotrocha | ||

| + | Didymodactylus | ||

| + | Dissotrocha | ||

| + | Embata | ||

| + | Macrotrachela | ||

| + | Mniobia | ||

| + | Philodina | ||

| + | Pleuretra | ||

| + | Rotaria | ||

| + | Zelinkiella | ||

| + | *Adinetidae | ||

| + | Adineta | ||

| + | Bradyscela | ||

| + | |||

| + | Tree of Life Web Project. 2006. Bdelloidea. Version 27 July 2006 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Bdelloidea/20454/2006.07.27 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/ | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

Revision as of 00:43, 1 May 2007

| Rotifers | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

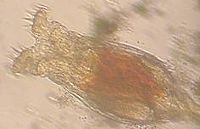

Philodina, feeding

| ||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||

| ||||||||

|

Rotifers comprise a phylum, Rotifera, of microscopic and near-microscopic, multicellular aquatic animals. They are pseudocoelomate invertebrates—that is, they have a fluid filled "false body cavity" that is only partly lined by mesoderm rather than a cavity within the mesoderm.

The name rotifer is derived from the Latin word for "wheel-bearer," referring to a characteristic crown of cilia surrounding the mouth of most rotifers, with the cilia movement in some species appearing under the microscope to whirl like a wheel (Baqai et al. 2000).

Rotifers were first described by John Harris in 1696 (Hudson and Gosse 1886). Leeuwenhoek is mistakenly given credit for being the first to describe rotifers, but Harris had produced sketches in 1703. There are over 1,800 known species of rotifers.

Description

Most rotifers are around 0.1-0.5 mm long (Towle 1989), but a few species, such as Rotaria neptunia, may exceed a millimeter (Baqau et al. 2000, Orstan 1999).

Rotifers are common in freshwater throughout the world, with a few saltwater species. They can be found in both still water (lake bottoms) and flowing water (rivers and streams) environments, as well as in moist soil in the films of water around soil particles, on mosses and lichens, in rain gutters and puddles, in leaf litter, on mushrooms, and even on freshwater crustaceans and larvae of aquatic insects (Baqai et al. 2000; Orstan 1999).

Most rotifers are free swimming, but others move by inchworming along the substrate, and some are sessile, living inside tubes or gelatinous holdfasts. About 25 species are colonial (i.e. Sinantherina semibullata), either sessile or planktonic.

In addition to their name meaning "wheel-bearer," rotifers also have been called wheel animalcules) from the corona (crown), which is composed of several ciliated tufts around the mouth that in motion resemble a wheel. These create a current that sweeps food into the mouth, where it is chewed up by a characteristic pharynx (mastax) containing tiny jaws. It also pulls the animal, when unattached, through the water. Most free-living forms have pairs of posterior toes to anchor themselves while feeding.

Rotifers feed on unicellular algae, bacteria, protozoa, and dead and decomposing organic materials, and are preyed upon by shrimp and crabs, among other secondary consumers (Towle 1989; Baqai et al. 2000).

Rotifers have Bilateral symmetry. They lack any skeleton (Towle 1989); however, they have a variety of different shapes because of a well-developed cuticle and hydrostatic pressure within the pseudocoelom. This cuticle may be thick and rigid, giving the animal a box-like shape, or flexible, giving the animal a worm-like shape; such rotifers are respectively called loricate and illoricate.

Rotifers have specialized organ systems. The rotifer nervous system is composed of anterior ganglia, two anterior eyespots, and two long nerves that transverse the length of the body (Towle 1989). Rotifers have a complete digestive tract with a mouth and anus.

Like many other microscopic animals, adult rotifers frequently exhibit eutely: They have a fixed number of cells within a species, usually on the order of one thousand.

Reproduction

Rotifers have the ability to alternate reproduction by sexual or asexual means, depending on their class and the varied conditions of their environment. In the Class Monogononta, rotifers reproduce by alternating means, though most times asexually.

Males in the Class Monogononta may be either present or absent depending on the species and environmental conditions. In the absence of males, reproduction is by parthenogenesis and results in clonal offspring that are genetically identical to the parent. Individuals of some species form two distinct types of parthenogenetic eggs; one type develops into a normal parthenogenetic female, while the other occurs in response to a changed environment and develops into a degenerate male that lacks a digestive system, but does have a complete male reproductive system that is used to inseminate females thereby producing fertilized 'resting eggs'. Resting eggs develop into zygotes that are able to survive extreme environmental conditions such as may occur during winter or when the pond dries up. These eggs resume development and produce a new female generation when conditions improve again. The life span of monogonont females varies from a couple of days to about three weeks.

Bdelloid rotifers are unable to produce resting eggs, but many can survive prolonged periods of adverse conditions after desiccation. This facility is termed anhydrobiosis, and organisms with these capabilities are termed anhydrobionts. Under drought conditions, bdelloid rotifers contract into an inert form and lose almost all body water; when rehydrated, however, they resume activity within a few hours. Bdelloids can survive the dry state for prolonged periods, with the longest well-documented dormancy being nine years. While in other anhydrobionts, such as the brine shrimp, this desiccation tolerance is thought to be linked to the production of trehalose, a non-reducing disaccharide (sugar), bdelloids apparently lack the ability to synthesise trehalose.

Bdelloid rotifer genomes contain two or more divergent copies of each gene, suggesting a long term asexual evolutionary history (Welch etal 2004). Four copies of hsp82 are, for example, found. Each is different and found on a different chromosome excluding the possibility of homozygous sexual reproduction.

Taxonomy

Rotifers are typically divided into three classes, Monogononta, Bdelloidea, and Seisonidea, although Acanthocephala (spiny-headed worms, thorny-headed worms) are sometimes placed with Rotifera as well (. Monogononta has about 1,500 species, Bdelloidea has about 350 species comprising four families and 19 genera, and Seisonidea has two known species (Baqai et al. 2000, Meselson 2007)). Bdelloid rotifers are small, freshwater invertebrates.

There are about 2000 species, divided into two classes. The parasitic Acanthocephala may belong among the rotifers as well. These phyla belong in a group called the Platyzoa.

- Habrotrochidae

Habrotrocha Otostephanos Scepanotrocha

- Philodinavidae

Abrochtha Henoceros Philodinavus

- Philodinidae

Anomopus Ceratotrocha Didymodactylus Dissotrocha Embata Macrotrachela Mniobia Philodina Pleuretra Rotaria Zelinkiella

- Adinetidae

Adineta Bradyscela

Tree of Life Web Project. 2006. Bdelloidea. Version 27 July 2006 (temporary). http://tolweb.org/Bdelloidea/20454/2006.07.27 in The Tree of Life Web Project, http://tolweb.org/

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

J.L.M. Welch, D.B.M Welch, and M. Meselson. Cytogenic evidence for asexual evolution of bdelloid rotifers. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci., Feb. 2004 vol. 101, no. 6, pp.1618-1621

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.