Presbyopia

Presbyopia (Greek word "presbys" (πρέσβυς), meaning "old person") describes the condition where the eye exhibits a progressively diminished ability to focus on near objects with age. Presbyopia's exact mechanisms are not known with certainty, however, the research evidence most strongly supports a loss of elasticity of the crystalline lens, although changes in the lens's curvature from continual growth and loss of power of the ciliary muscles (the muscles that bend and straighten the lens) have also been postulated as its cause.

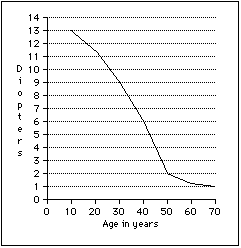

Similar to gray hair and wrinkles, presbyopia is a symptom caused by the natural course of aging. The first symptoms (described below) are usually first noticed between the ages of 40-50. The ability to focus on near objects declines throughout life, from an accommodation of about 20 dioptres (ability to focus at 50 mm away) in a child to 10 dioptres at 25 (100 mm) and leveling off at 0.5 to 1 dioptre at age 60 (ability to focus down to 1-2 meters only).

Overview

The lens is a transparent, biconvex (lentil-shaped) structure in the eye that, along with the cornea, helps to refract light to be focused on the retina. The lens, by changing shape, functions to change the focal distance of the eye so that it can focus on objects at various distances, thus allowing a sharp real image of the object of interest to be formed on the retina. The lens is also known as the crystalline lens.

The lens is flexible and its curvature is controlled by ciliary muscles through the zonules. By changing the curvature of the lens, one can focus the eye on objects at different distances from it. This process is called accommodation. At short focal distance the ciliary muscles contract, zonule fibers loosen, and the lens thickens, resulting in a rounder shape and thus high refractive power. Changing focus to an object at a distance requires the stretching of the lens by the ciliary muscles, which flattens the lens and thus increases the focal distance.

Symptoms

The first symptoms most people notice are, difficulty reading fine print, particularly in low light conditions, eyestrain when reading for long periods, blur at near or momentarily blurred vision when transitioning between viewing distances. Many advanced presbyopes complain that their arms have become "too short" to hold reading material at a comfortable distance.[1]

Presbyopia, like other focus defects, becomes much less noticeable in bright sunlight. This is a result of the iris closing to a pinhole, so that depth of focus, regardless of actual ability to focus, is greatly enhanced, as in a pinhole camera which produces images without any lens at all. Another way of putting this is to say that the circle of confusion, or blurredness of image, is reduced, without improving focusing.

A delayed onset of seeking correction for presbyopia has been found among those with certain professions and those with miotic pupils.[2] In particular, farmers and housewives seek correction later, whereas service workers and construction workers seek eyesight correction earlier.

Focusing mechanism of the eye

In optics, the closest point at which an object can be brought into focus by the eye is called the eye's near point. A standard near point distance of 25 cm is typically assumed in the design of optical instruments, and in characterizing optical devices such as magnifying glasses.

There is some confusion in articles and even textbooks over how the focusing mechanism of the eye actually works. In the classic book, 'Eye and Brain' by Gregory, for example, the lens is said to be suspended by a membrane, the 'zonula', which holds it under tension. The tension is released, by contraction of the ciliary muscle, to allow the lens to fatten, for close vision. This would seem to imply that the ciliary muscle, which is outside the zonula must be circumferential, contracting like a sphincter, to slacken the tension of the zonula pulling outwards on the lens. This is consistent with the fact that our eyes seem to be in the 'relaxed' state when focusing at infinity, and also explains why no amount of effort seems to enable a myopic person to see further away. Many texts, though, describe the 'ciliary muscles' (which seem more likely to be just elastic ligaments and not under any form of nervous control) as pulling the lens taut in order to focus at close range.[citation needed] This has the counterintuitive effect of steepening the lens centrally (increasing its power) and flattening peripherally.

Presbyopia and the 'payoff' for the nearsighted

Many people with myopia are able to read comfortably without eyeglasses or contact lenses even after age 40. However, their myopia does not disappear and the long-distance visual challenges will remain. Myopes with astigmatism will find near vision better though not perfect without glasses or contact lenses once presbyopia sets in, but the greater the amount of astigmatism the poorer their uncorrected near vision. Myopes considering refractive surgery are advised that surgically correcting their nearsightedness may actually be a disadvantage after the age of 40 when the eyes become presbyopic and lose their ability to accommodate or change focus because they will then need to use glasses for reading. A surgical technique offered is to create a "reading eye" and a "distance vision eye", a technique commonly used in contact lens practice, known as monovision.

Treatment

Template:Cleanup-section Template:Advert Presbyopia is not routinely curable - though tentative steps toward a possible cure suggest that this may be possible - but the loss of focusing ability can be compensated for by corrective lenses including eyeglasses or contact lenses. In subjects with other refractory problems, Convex lenses are used. In some cases, the addition of bifocals to an existing lens prescription is sufficient. As the ability to change focus worsens, the prescription needs to be changed accordingly.

In order to reduce the need for bifocals or reading glasses, some people choose contact lenses to correct one eye for near and one eye for far with a method called "monovision". Monovision sometimes interferes with depth perception. There are also newer bifocal or multifocal contact lenses that attempt to correct both near and far vision with the same lens.

[3].

Controversially, eye exercises have been quoted as a way to delay the onset of Presbyopia [1].

- Nutrition

At least one scientific study reported that taking lutein supplements or otherwise increasing the amount of lutein in the diet resulted in an improvement in visual acuity,[4] while another study suggested that lutein supplementation might slow aging of the lens.[5] Lutein is found naturally in both the lens of the eye and the macula, the central area of the retina.

Surgery

New surgical procedures may also provide solutions for those who do not want to wear glasses or contacts, including the implantation of accommodative intraocular lenses (IOLs). Scleral expansion bands, which increase the space between the ciliary body and lens, have not been found to provide predictable or consistent results in the treatment of presbyopia.[6]

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ Robert Abel, The Eye Care Revolution: Prevent and Reverse Common Vision Problems, Kensington Books, 2004.

- ↑ Garcia Serrano JL, Lopez Raya R, Mylonopoulos Caripidis T. "Variables related to the first presbyopia correction." Arch Soc Esp Oftalmol. 2002 Nov;77(11):597-604. PMID 12410405.

- ↑ Guoqiang Li et al, Switchable electro-optic diffractive lens with high efficiency for ophthalmic applications", Proceedings of National Academy of Sciences USA, V103, 6100-6104 (2006).

- ↑ Nutrition Volume 19, Issue 1, pp. 21-24. Retrieved 2008-04-14.

- ↑ Lens Aging in Relation to Nutritional Determinants and Possible Risk Factors for Age-Related Cataract. Retrieved 2008-04-15.

- ↑ Malecaze FJ, Gazagne CS, Tarroux MC, Gorrand JM. "Scleral expansion bands for presbyopia." Ophthalmology. 2001 Dec;108(12):2165-71. PMID 11733253.

- Souder, E. 2002. Trachoma. Pages 2713 to 2715 in J.L. Longe (ed.), The Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine, 2nd edition, volume 4. Detroit: Gale Group/Thomson Learning. ISBN 0787654930.

External links

- Correct presbyopia using Conductive Keratoplasty (CK)

- Eyes over 40

- Presbyopia

- Options for today's Presbyopes

- Vision Over 40

- Presbyopia at MedLinePlus Medical Encyclopedia

| Pathology of the eye (primarily H00-H59) | |

|---|---|

| Eyelid, lacrimal system and orbit | Stye - Chalazion - Blepharitis - Entropion - Ectropion - Lagophthalmos - Blepharochalasis - Ptosis - Xanthelasma - Trichiasis - Dacryoadenitis - Epiphora - Exophthalmos - Enophthalmos |

| Conjunctiva | Conjunctivitis - Pterygium - Subconjunctival hemorrhage |

| Sclera and cornea | Scleritis - Keratitis - Corneal ulcer - Snow blindness - Thygeson's superficial punctate keratopathy - Fuchs' dystrophy - Keratoconus - Keratoconjunctivitis sicca - Arc eye - Keratoconjunctivitis - Corneal neovascularization - Kayser-Fleischer ring - Arcus senilis |

| Iris and ciliary body | Iritis - Uveitis - Iridocyclitis - Hyphema - Persistent pupillary membrane |

| Lens | Cataract - Aphakia |

| Choroid and retina | Retinal detachment - Retinoschisis - Hypertensive retinopathy - Diabetic retinopathy - Retinopathy - Retinopathy of prematurity - Macular degeneration - Retinitis pigmentosa - Macular edema - Epiretinal membrane - Macular pucker |

| Ocular muscles, binocular movement, accommodation and refraction | Strabismus - Ophthalmoparesis - Progressive external ophthalmoplegia - Esotropia - Exotropia - Refractive error - Hyperopia - Myopia - Astigmatism - Anisometropia - Presbyopia - Fourth nerve palsy - Sixth nerve palsy - Kearns-Sayre syndrome - Esophoria - Exophoria - Duane syndrome - Convergence insufficiency - Internuclear ophthalmoplegia - Aniseikonia |

| Visual disturbances and blindness | Amblyopia - Leber's congenital amaurosis - Subjective (Asthenopia, Hemeralopia, Photophobia, Scintillating scotoma) - Diplopia - Scotoma - Anopsia (Binasal hemianopsia, Bitemporal hemianopsia, Homonymous hemianopsia, Quadrantanopia) - Color blindness (Achromatopsia) - Nyctalopia - Blindness/Low vision |

| Commonly associated infectious diseases | Trachoma - Onchocerciasis |

| Other | Glaucoma - Floater - Leber's hereditary optic neuropathy - Red eye - Argyll Robertson pupil - Keratomycosis - Xerophthalmia - Aniridia |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.