Orinoco River

| Orinoco | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Bridge over the Orinoco at Ciudad Bolívar, Venezuela

| |||

| Countries | Venezuela, Colombia | ||

| Length | 2,410 km (1,498 miles) | ||

| Watershed | 880,000 km² (339,770 miles²) | ||

| Discharge | mouth | ||

| - average | 33,000 meters³/sec. (1,165,384 feet³/sec.) | ||

| Source | |||

| - location | Cerro Delgado-Chalbaud, Parima, Venezuela + Brazil | ||

| - coordinates | coord}}{{#coordinates:02|19|05|N|63|21|42|W|landmark | name=

}} | |

| - elevation | 1,047 meters (3,435 feet) | ||

| Mouth | Delta Amacuro | ||

| - location | Atlantic Ocean, Venezuela | ||

| - elevation | 0 meters (0 feet) | ||

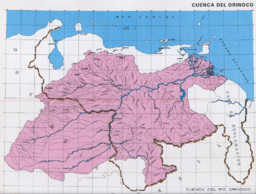

The Orinoco is one of the longest rivers in South America at 1,497.5 miles (2,410 km²) and one of the largest river systems in the world. Its vast drainage basin, sometimes called the Orinoquia (especially in Colombia) covers over 340,000 square miles (880,000 km²), 76.3% in Venezuela with the remainder in Colombia and Brazil. The name Orinoco means “a place to paddle” in the language of the Warao, an indigenous people inhabiting eastern Venezuela and western Guyana. Alternate common spellings of Warao are Waroa, Guarauno, Guarao, and Warrau. The term Warao translates as "the boat people", styling after the Warao's lifelong and intimate connection to water. The Orinoco and its thousands of tributaries are the major transportation system for eastern and interior Venezuela and the llanos of Colombia. However, since river navigation is declining in every country, many of the old waterways along the Orinoco watershed are now an obstacle to land communications more than a useful commercial route.

Geography

Forming part of the border between Venezuela and Colombia, the Orinoco course flows in a wide ellipsoidal arc, surrounding the Guiana Shield, then entering the Atlantic Ocean near the island of Trinidad. It is divided in four stretches of unequal length that roughly correspond to the longitudinal zonation of a typical large river:

- Upper Orinoco, 144 miles (242 km) long, from its headwaters to the rapids Raudales de Guaharibos, a narrow river with waterfalls that flows through mountainous landscape in a northwesterly direction

- Middle Orinoco, 450 miles (750 km) long, divided into two sectors, the first of which is about 280 miles (480 km) long and has a general westward direction down to the confluence with the Atabapo and Guaviare rivers at San Fernando de Atabapo; the second flows northward, for about 168 miles (270 km), along the Venezuelan–Colombian border, flanked on both sides by the westernmost granitic upwellings of the Guiana Shield which impede the development of a flood plain, to the Atures rapids near the confluence with the Meta River at Puerto Carreño

- Lower Orinoco, 596 miles (959 km) long with a well-developed alluvial plain, flows in a northeast direction, from Atures rapids down to Piacoa in front of Barrancas

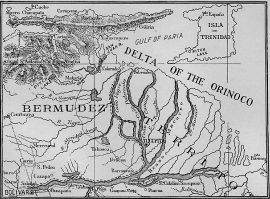

- Delta Amacuro, 124 miles (200 km) long that empties into the Gulf of Paría and the Atlantic Ocean, a very large delta (some 8.7 square miles (22.500 km²) and 230 miles (370 km) at its widest).

At its mouth it forms a wide delta that branches off into hundreds of rivers and waterways that flow through 15,830 square miles (41,000 km²) of swampy forests. In the rainy season the Orinoco can swell to a breadth of nearly 14 miles (22 km) and a depth of 328 feet (100 meters).

Most of the important Venezuelan rivers are tributaries of the Orinoco, the largest being the Caroní, which joins it at Puerto Ordaz, close to the Llovizna Falls. A peculiarity of the Orinoco river system is the Casiquiare canal, which starts as an arm of the Orinoco, and finds its way to the Rio Negro, a tributary of the Amazon, thus forming a “natural canal” between Orinoco and Amazon.

Climate

The Orinoco basin has a tropical climate with only slight changes in average temperatures throughout the year. However, unlike the temperatures, rainfall varies considerably and divides the year into only two seasons—a rainy winter season that runs from April through October or November and a dry summer season that is from November through March or April. The precipitation in the entire basin area varies greatly with the coastal regions receiving less than 20 inches and some inland areas enough rainfall to be considered a rain forest. The Llanos, a treeless savanna, will be extremely dry from January through April with temperatures rising above 95° (35°C), then experience flooding from June to October. Villavicencio, Colombia, an area near the Andes, receives the highest precipitation with 180 inches annually. Puerto de Nutrias, Venezuela, toward the central plains receives less, about 45 inches.

Flora and fauna

Many of the natural trees in the region have been reduced greatly by deforestation. Surviving in the open savanna are mainly trees that have adapted to the dry conditions, such as the chaparro (scrub oak) and the dwarf palm, as well as sedges and swamp grasses. Along the river growing in rich alluvial soil are the morichales, named for the miriti or moriche palm.

There are over 1,000 species of birds found in the region, such as the scarlet ibis, umbrella bird, bellbird, flamingos, and colorful parrots. Fish are plentiful as well with electric eels, catfish often weighing over 200 pounds, and the Caribe Piranha or Pygocentrus cariba. It is the most aggressive piranha of the Characidae family.[citation needed]. The Boto, also known as the Amazon River Dolphin that can grow up to nine feet in length, boa constrictors, and caimans are also known to inhabit the Orinoco River system. The Orinoco Crocodile, reaching more than 20 feet, is one of the rarest reptiles in the world, with fewer than 250 specimens remaining in the wild. Its present-day range in the wild is restricted to the Orinoco River Basin.

Major rivers in the Orinoco Basin

- Apure: from Venezuela through the east into the Orinoco

- Arauca: from Colombia to Venezuela east into the Orinoco

- Atabapo: from the Guiana Highlands of Venezuela north into the Orinoco

- Caroní: from the Guiana Highlands of Venezuela north into the Orinoco

- Casiquiare canal: in SE Venezuela, a distributary from the Orinoco flowing west to the Negro River, a major afluent to the Amazon

- Caura: from eastern Venezuela (Guiana Highlands) north into the Orinoco

- Guaviare: from Colombia east into the Orinoco

- Inírida: from Colombia northeast into the Guaviare.

- Meta: from Colombia, border with Venezuela east into the Orinoco

- Ventuari: from eastern Venezuela (the Guiana Highlands) southwest into the Orinoco

- Vichada: from Colombia east into the Orinoco

History

Although the mouth of the Orinoco in the Atlantic Ocean was discovered by Columbus on his third voyage (1498-08-01), its source at the Cerro Delgado-Chalbaud, in the Parima range, on the Venezuelan-Brazilian border, at 1,047 m of elevation ({{#invoke:Coordinates|coord}}{{#coordinates:02|19|05|N|63|21|42|W| | |name= }} ), was only explored in 1951, 453 years later, by a joint Venezuelan-French team.

The delta of the Orinoco, and tributaries in the eastern llanos such as the Apure and Meta, were explored in the 16th Century by German expeditions under Ambrosius Ehinger and his successors. In 1531 Diego de Ordaz, starting at the principal outlet in the delta, the Boca de Navios, sailed up the river to the Meta, and Antonio de Berrio sailed down the Casanare, to the Meta, and then down the Orinoco and back to Coro.

Alexander von Humboldt explored the basin in 1800, reporting on the pink river dolphins, and publishing extensively on the flora and fauna.[1]

Prior to the mid-1900s, mainly small villages, missionary stations, and ranches, better known as hatos (haciendas), existed along the rivers of the region. Industrial and urban development came about in 1937 at El Tigre and in 1948 in Barinas when oil and gas were struck.

Agriculture began to increase and expand in the 1950s and a concentration of small farms developed around Barinas, Guanare, San Fernando de Apure, and Acarigua in Venezuela. Built on higher ground to escape the seasonal flooding, towns in the Venezuelan Llanos were built similar to those in Spain with the streets in a grid pattern surrounding the central plaza. Populations often rose to over 10,000. The Colombian Llanos region was not as populated except in the area near Ciudad Guayana in the Guiana Highlands.

Indigenous Peoples

Most of the indigenous population lives within the Orinoco River Basin, with the exception of the Guajiros of Lake Maracaibo. The groups include the Warrau (Waroa) who live in the delta region in palaftos, small wooden structures built on stilts over water, the Guaica (Waica) and the Maquiritare (Makiritare) who live in the southern uplands, the Guahibo and the Yaruro who live in the western Llanos, and the Yanomami who live in round wood and thatch houses called shabonos. These indigenous tribes have lived in union with the rivers relying on them for food, transportation, and communication for centuries.

Economy

The river is navigable for most of its length. Large river steamers carry cargo as far as Puerto Ayacucho and the Atures Rapids, a distance of 700 miles (1,127 km) from the delta. Dredging enables ocean vessels to travel 270 miles (435 km) upstream as far as the commercial port and industrial city of Ciudad Bolívar, the confluence of the Caroní River, in order to mine iron ore deposits. The Orinoco river deposits contain extensive tar sands in the Orinoco oil belt, which may be a source of future oil production.[2]

Since World War II many roads have been constructed in the Venezuelan Llanos and two important bridges. The mile-long bridge across the Orinoco River at Ciudad Bolívar connecting the Llanos and the Guiana region and a bridge connecting the old Orinoco port of San Félix with the new industrial town of Puerto Ordaz. The bridges were completed in the 1960s.

Concerns

The vast tropical grasslands of the Llanos have been used mainly for cattle farming, but soil degradation resulting from overgrazing has become a major concern. Major change in industrial growth was made possible by the building of the Macagua and Guri dams and has made Ciudad Guayana a center for the production of aluminum, paper, and steel, causing concerns about pollution to the region.

On an international level of concern is the control over Venezuela’s last privately run oil fields in May 2007 by President Hugo Chavez’s government. The Orinoco River Basin is the world’s largest known single petroleum deposit with a potential of holding 1.2 trillion barrels of extra-heavy crude. Chavez claims that for Venezuela to be a socialist state it must have control over its natural resources. Outside companies believe they still have some leverage due to the fact that without their experience, Venezuela’s inefficient state oil company cannot transform Orinoco’s tar-like crude into oil that is marketable.

Notes

- ↑ Helferich. Gerard (2004) Humboldt's cosmos : Alexander von Humboldt and the Latin American journey that changed the way we see the world Gotham Books, New York, ISBN 1-59240-052-3 ;

- ↑ Forero, Juan (1 June 2006) "For Venezuela, A Treasure In Oil Sludge" New York Times Vol. 155 Issue 53597, pC1-C6;

Sources and Further Reading

- Stark, James Henry. 1897. Stark's guide-book and history of Trinidad including Tobago, Granada, and St. Vincent; also a trip up the Orinoco and a description of the great Venezuelan pitch lake. Boston: J.H. Stark.

- MacKee, Edwin D. 1989. Sedimentary structures and textures of Río Orinoco channel sands, Venezuela and Columbia. [Washington, D.C.]: United States government printing office.

- Weibezahn, Franz H., Haymara Alvarez, and William M. Lewis. 1990. El Rio Orinoco como ecosistema = The Orinoco River as an ecosystem. Caracas: Electrificación del Caroní. ISBN 9802370347 and ISBN 9789802370344

- Rawlins, Carol. 1999. The Orinoco River. Watts library. New York: Franklin Watts. ISBN 0531117405 and ISBN 9780531117408

External Links

- Hamre, Bonnie. Orinoco River. About: South America for Visitors. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Orinoco River & Flooded Forests - A Global Ecoregio. World Wildlife Foundation. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Acebes, See H. Orinoco. Info Please. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

- Hydrology. Geo-Enviornmental Characterization of the Delta del Orinoco. Retrieved May 15, 2007.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.