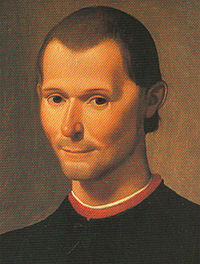

Niccolo Machiavelli

- Niccolo (Nick)Machiavelli redirects here. For the card game, see Citadels.

Niccolò di Bernado dei Machiavelli (May 3, 1469 – June 21, 1527) was a political philosopher, musician, poet, and romantic comedic playwright. Machiavelli is a key figure of the Renaissance, most known for his treatises on realist political theory (The Prince) on the one hand and idealistic Republicanism (Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio) on the other.

Life

Machiavelli was born into a tumultuous era, one that saw Popes leading armies and wealthy city-states of Italy falling one after another into the hands of foreign powers — France, Spain, the Holy Roman Empire. It was a time of constantly shifting alliances, mercenaries who changed sides without warning, governments rising and falling in the space of a few weeks, and on top of all of this the rise of Lutheranism, culminating in the sack of Rome at the hands of rampaging German soldiers in 1527, the first time in nearly twelve centuries. Machiavelli did not live to see this final humiliation but steeped as he was in the Byzantine politics of the age, it is no wonder that he turned his intelligence to analyzing the successes and failures he saw around him.

Machiavelli was born in Florence, the second son of Bernardo di Niccolò Machiavelli and his wife Bartolommea di Stefano Nelli. His father was a well-known lawyer who belonged to an impoverished branch of an influential old Florentine family. After receiving an education that allowed him to cultivate a good grasp of the Latin and Italian classics he entered government service as a clerk in 1494.

That same year, Florence expelled the Medici family, who had ruled the city for nearly sixty years, and restored the republic. Machiavelli was named as a member of the Council responsible for diplomatic negotiations and military matters. From 1499 to 1512, he was sent on a number of diplomatic missions to the court of Louis XII in France, Ferdinand II of Spain, and the Papacy in Rome. From 1502 to 1503, Machiavelli was a witness to the effective statebuilding methods of the soldier/churchman Cesare Borgia, an immensely capable general and statesman who was at that time engaged in enlarging his holdings in central Italy through a mixture of audacity, prudence, self-reliance, firmness and, not infrequently, cruelty.

From 1503 to 1506, Machiavelli was responsible for the Florentine militia including the defense of the city. Machiavelli distrusted mercenaries (a philosophy expounded at length in the Discorsi) and much preferred a citizen militia.

In August 1512, following a tangled series of battles, treaties, and alliances, the Medici with the help of Pope Julius II regained power in Florence and the republic was dissolved. Machiavelli, having played a significant role in the republic's anti-Medici government, was removed from office and in 1513 he was accused of conspiracy and arrested. Although tortured on the rack he denied his involvement and was eventually released. He retired to his estate at San Casciano near Florence and began writing the treatises that would ensure his place in the development of political philosophy.

In a famous letter to his friend Francesco Guicciardini, historian and Florentine diplomat, Machiavelli described how he spent his days:

"When evening comes, I return home [from work and from the local tavern] and go to my study. On the threshold I strip naked, taking off my muddy, sweaty workaday clothes, and put on the robes of court and palace, and in this graver dress I enter the courts of the ancients and am welcomed by them, and there I taste the food that alone is mine, and for which I was born. And there I make bold to speak to them and ask the motives of their actions, and they, in their humanity reply to me. And for the space of four hours I forget the world, remember no vexation, fear poverty no more, tremble no more at death; I pass indeed into their world." (The Literary Works of Machiavelli, trans. Hale. Oxford 1961, page 139)

Machiavelli died in Florence in 1527. His resting place is unknown; however a cenotaph in his honor was placed at the Church of Santa Croce in Florence.

Works

The Prince

Machiavelli's best known work is The Prince, in which he describes the arts by which a Prince can retain control of his kingdom. He focuses primarily on what he calls the principe nuovo or "new prince," under the assumption that a hereditary prince has an easier task since the people are accustomed to him. All a hereditary prince need do is carefully maintain the institutions that the people are used to; a new prince has a much more difficult task since he must stabilize his newfound power and build a structure that will endure. This task requires the Prince to be publicly above reproach but privately may require him to do things that are evil in order to achieve the greater good.

A careless reading of The Prince could easily lead one to believe that its central argument is "the ends justify the means," that any evil action can be justified if it is done for a good purpose. This is a limited interpretation, however, because Machiavelli placed a number of restrictions on evil actions. First, he specified that the only acceptable end was the stabilization and health of the state; individual power for its own sake is not an acceptable end and does not justify evil actions. Second, Machiavelli does not dispense entirely with morality nor advocate wholesale selfishness or degeneracy. Instead he clearly lays out his definition of, for example, the criteria for acceptable cruel actions (it must be swift, effective, and short-lived). Notwithstanding the mitigating themes in The Prince, the Catholic church put the work in its Index Librorum Prohibitorum and it was viewed in a negative light by many Humanists such as Erasmus.

The term "Machiavellian" was adopted by some of Machiavelli's contemporaries, often used in the introductions of political tracts of the sixteenth century that offered more 'just' reasons of state, most notably those of Jean Bodin and Giovanni Botero. The pejorative term Machiavellian as it is used today is thus a misnomer, as it describes one who deceives and manipulates others for gain; whether the gain is personal or not is of no relevance, only that any actions taken are only important insofar as they affect the results. It fails to include some of the more moderating themes found in Machiavelli's works and the name is now associated with the extreme viewpoint.

Discorsi

If The Prince was Machiavelli's textbook on a monarchy, his Discourse on the First Ten Books of Titus Livy (which comprise the early history of Rome) is a paean to the Republic. The Discorsi is a series of lessons on how a republic should be started, structured and maintained. Each one begins with a principle, supports it with examples from Livy's history of Rome or other ancient models, and then gives what would be for Machiavelli a contemporary example from 15th or 16th century Italy. Many of the ideas set forth in the Discorsi, including the concept of checks and balances, the strength of a tripartite structure, and the superiority of a republic over a principality, are as valid today as they were six centuries ago and clear applications of his practical political philosophy can be found in the governments of many democracies today including the United States.

Other works

Machiavelli also wrote plays (Clizia, Mandragola), poetry (Sonetti, Canzoni, Ottave, Canti carnascialeschi) and novels (Belfagor arcidiavolo) as well as translating classical works.

- Discorso sopra le cose di Pisa, 1499

- Del modo di trattare i popoli della Valdichiana ribellati, 1502

- Del modo tenuto dal duca Valentino nell' ammazzare Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, etc., 1502 (Description of the Methods Adopted by the Duke Valentino when Murdering Vitellozzo Vitelli, Oliverotto da Fermo, the Signor Pagolo, and the Duke di Gravina Orsini)

- Discorso sopra la provisione del danaro, 1502

- Decennale primo (poem in terza rima), 1506

- Ritratti delle cose dell'Alemagna, 1508-1512

- Decennale secondo, 1509

- Ritratti delle cose di Francia, 1510

- Discorsi sopra la prima deca di Tito Livio, 3 vols., 1512-1517 (Discourses on Livy)

- Il Principe, 1513 (The Prince)

- Andria, comedy translated from Terence, 1517

- Mandragola, prose comedy in five acts, with prologue in verse, 1518 (The Mandrake)

- Della lingua (dialogue), 1514

- Clizia, comedy in prose, 1525

- Belfagor arcidiavolo (novel), 1515

- Asino d'oro (poem in terza rima, a new version of the classic work by Apuleius), 1517 (The Golden Ass)

- Dell'arte della guerra, 1519-1520 (The Art of War)

- Discorso sopra il riformare lo stato di Firenze, 1520

- Sommario delle cose della citta di Lucca, 1520

- Vita di Castruccio Castracani da Lucca, 1520 (The Life of Castruccio Castracani of Lucca)

- Istorie fiorentine, 8 books, 1520-1525 (Florentine Histories - commissioned by Giulio di Giuliano de' Medici who went on to become Pope Clement VII).

- Frammenti storici, 1525.

Machiavelli in popular culture

- The Japanese Rock band Dir en grey featured a song on their 2005(Japan)/2006(US) album "Withering to death" titled "Machiavellism".

- Machiavelli was ranked #79 on Michael H. Hart's list of the most influential figures in history.

- In his book Warrior Politics, author and journalist Robert D. Kaplan cites Machiavelli as a proponent of a "pagan ethos", which Kaplan feels is preferable to Judeo-Christian morality in decision-making by politicians and businessmen. It would not, however, be correct to assume that he believed in immoral acts such as genocide despite the fact that he did not always condemn them.

- The late Tupac Shakur took on the alter-ego of "Makaveli", a modified form of Machiavelli's name, shortly before his death in 1996. Later, an album was released under the alias "Makaveli", The Don Killuminati: 7 Day Theory, which sold over 7 million copies.

- In comedian Jon Stewart's satirical America: The Book, Machiavelli is listed as having "No Impact" on American Democracy.

- In her book In the Footsteps of Mr. Kurtz, journalist Michela Wrong writes that Zairian dictator Mobutu Sese Seko read Machiavelli's writings and considered him, as well as Winston Churchill and Charles de Gaulle, one of the greatest influences on his thinking.

- The satirical business book, What Would Machiavelli Do? (title a take-off of the phrase 'What would Jesus do?') by 'Stanley Bing'.

See also

- Renaissance Philosophy

- Political Philosophy

- Philosophy of war

- Francesco Guicciardini

- Republicanism

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Wootton, David. Selected political writings of Niccolò Machiavelli. Indianapolis : Hackett Pub. Co., c1994.

- Magee, Brian. The Story of Philosophy. New York : DK Publishing, Inc., c2001, pp. 72 and 73.

- Baron, Hans. "Machiavelli: the Republican Citizen and Author of 'The Prince'" in Machiavelli by Dunn and Harris, 1997.

Further reading

- Bock, Gisela; Skinner, Quentin; and Viroli, Maurizio, ed. Machiavelli and Republicanism. Cambridge University Press, 1990. 316 pp.

- Donaldson, Peter S. Machiavelli and Mystery of State. Cambridge University Press, 1989. 227 pp.

- Najemy, John M. "Baron's Machiavelli and Renaissance Republicanism." American Historical Review 1996 101(1): 119-129. Issn: 0002-8762 Fulltext: in Jstor and Ebsco

- Pocock, J. G. A. The Machiavellian Moment: Florentine Political Thought and the Atlantic Republican Tradition (2003)

- Soll, Jacob. Publishing The Prince: History, Reading and the Birth of Political Criticism. U. of Michigan Press, 2005. 202 pp.

- Sullivan, Vickie B., ed. The Comedy and Tragedy of Machiavelli: Essays on the Literary Works. Yale U. Press, 2000. 238 pp.

- Sullivan, Vickie B. Machiavelli's Three Romes: Religion, Human Liberty, and Politics Reformed. Northern Illinois U. Press, 1996. 235 pp.

- Viroli, Maurizio. Niccolò's Smile: A Biography of Machiavelli Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2000. 288 pp.

- Whelan, Frederick G. Hume and Machiavelli: Political Realism and Liberal Thought Lexington, 2004. 416 pp.

External links

- eMachiavelli.com, The official site for the works and summaries of Machiavelli

- Works by Machiavelli. Project Gutenberg

- "The Seven Books on the Art of War" at the Marxists Internet Archive

- Works by Niccolò Machiavelli: text, concordances and frequency list

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Niccolò Machiavelli |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | Niccolo Machiavelli |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | Italian politician and political theorist |

| DATE OF BIRTH | 3 May, 1469 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Florence |

| DATE OF DEATH | 21 June, 1527 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Florence |

ar:نيكولو مكيافيلي bn:নিকোলো মাকিয়াভেলি bs:Niccolò Machiavelli bg:Николо Макиавели ca:Nicolau Maquiavel cs:Niccolò Machiavelli cy:Niccolò Machiavelli da:Niccolò Machiavelli de:Niccolò Machiavelli et:Niccolò Machiavelli es:Nicolás Maquiavelo eo:Makiavelo fr:Nicolas Machiavel ga:Niccolò Machiavelli gl:Nicolau Maquiavel ko:니콜로 마키아벨리 hr:Niccolò Machiavelli id:Niccolò Machiavelli is:Niccolò Machiavelli it:Niccolò Machiavelli he:ניקולו מקיאוולי ku:Niccolò Machiavelli la:Nicolaus Machiavellus lv:Nikolo Makjavelli lt:Nikolas Makiavelis hu:Niccolò Machiavelli mk:Николо Макијавели nl:Niccolò Machiavelli ja:ニッコロ・マキャヴェッリ no:Niccolò Machiavelli nn:Niccolò Machiavelli pl:Niccolò Machiavelli pt:Nicolau Maquiavel ro:Niccolò Machiavelli ru:Макиавелли, Никколо sq:Nikolo Makiaveli scn:Niccolò Machiavelli simple:Niccolo Machiavelli sk:Niccolò Machiavelli sl:Niccolo Machiavelli sr:Николо Макијавели fi:Niccolò Machiavelli sv:Niccolò Machiavelli tr:Niccolò Machiavelli uk:Макіавеллі Нікколо zh:尼可罗·马基亚维利

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.