Difference between revisions of "Mikhail Lermontov" - New World Encyclopedia

(Lermontov article) |

(Lermontov article) |

||

| Line 12: | Line 12: | ||

The family estate of Lermontov's father was much more modest than his mother's, so his father, Yuri Lermontov, like his father before him, entered military service. Having moved up the ranks of captain, he married the sixteen year old Mariya Arsenyeva, to the great dismay of her mother, Elizabeth Alekseevna. A year later after the marriage, on the night of October 3rd, 1814, Mariya Arsenieva gave birth to Mikhail Lermontov. Tension between Yuri and his maternal grandmother persisted. Soon after, Mariya Arsenieva fell ill and died in 1817 soon after Lermontov' birth. After her daughter's death, Elizabeth Alekseevna devoted all her care and attention to the child and his education, all the time fearing that his father might sooner or later run off with him. In this environment of his grandmother's pampering and continuing family tension, Lermontov developed into a precocious, sensitive youth with a fearful temper, which he proceeded to take out on the servants and the bushes in his grandmother's garden. | The family estate of Lermontov's father was much more modest than his mother's, so his father, Yuri Lermontov, like his father before him, entered military service. Having moved up the ranks of captain, he married the sixteen year old Mariya Arsenyeva, to the great dismay of her mother, Elizabeth Alekseevna. A year later after the marriage, on the night of October 3rd, 1814, Mariya Arsenieva gave birth to Mikhail Lermontov. Tension between Yuri and his maternal grandmother persisted. Soon after, Mariya Arsenieva fell ill and died in 1817 soon after Lermontov' birth. After her daughter's death, Elizabeth Alekseevna devoted all her care and attention to the child and his education, all the time fearing that his father might sooner or later run off with him. In this environment of his grandmother's pampering and continuing family tension, Lermontov developed into a precocious, sensitive youth with a fearful temper, which he proceeded to take out on the servants and the bushes in his grandmother's garden. | ||

| − | The intellectual atmosphere in which he was raised differed little from that of [[Aleksandr Pushkin|Pushkin]], though the domination of [[French language|French]] | + | The intellectual atmosphere in which he was raised differed little from that of [[Aleksandr Pushkin|Pushkin]], though the domination of [[French language|French]], the language of the Russian aristocracy, receded in favor of a growing interest in [[English language|English]], while [[Alphonse de Lamartine|Lamartine]] shared his interest with [[Lord Byron|Byron]]. In his early childhood Lermontov was educated by a certain Frenchman named Gendrot; but Gendrot was a poor pedagogue, so Elizabeth Alekseevna decided to take Lermontov to Moscow to prepare him better for the [[gymnasium (school)|gymnasium]]. In Moscow, Lermontov was introduced to Goethe and Schiller by a German pedagogue, Levy, and a short time after, in 1828, he entered the gymnasium. He showed himself to be an incredibly talented student, once completely stealing the show at an exam by, first, impeccably reciting some poetry, and second, successfully performing a violin piece. At the gymnasium he also became acquainted with the poetry of Pushkin and [[Vasily Zhukovsky|Zhukovsky]], and one of his friends, Catherine Hvostovaya, later described him as "''married to a hefty volume of Byron''". This friend had at one time been an object of Lermontov's affection, and to her he dedicated some of his earliest poems, one of the most remarkable ones being "''Нищий (У врат обители святой)''" (''The Beggar''). At that time, together with Lermontov's poetic passion, there also awoke an inclination for poisonous wit and cruel and sardonic humor. His ability to draw caricatures was matched by his ability to shoot someone down with a well aimed epigram or nickname. |

| − | + | After the academic gymnasium Lermontov entered [[Moscow University]] in August of [[1830]]. That same summer the final, tragic act of the family discord played out. Having been struck deep by his son's alienation, Yuri Lermontov left the Arseniev house for good, only to die a short time later. His father's death was a terrible loss for Lermontov, as is evidenced by a few of his poems: "''Forgive me, Will we Meet Again?''" and "''The Terrible Fate of Father and Son''". | |

| − | Lermontov's career at the University was very abrupt. While there, he was remembered for his aloofness and arrogant disposition; he attended the lectures rather faithfully, often reading a book in the corner of the auditorium, but rarely took part in student life. | + | Lermontov's career at the University was very abrupt. He spent two years there but received no degree. While there, he was remembered for his aloofness and arrogant disposition; he attended the lectures rather faithfully, often reading a book in the corner of the auditorium, but rarely took part in student life. |

| − | + | Like his father before him, he decided to enter the military. From [[1832]] to [[1834]] he attended the School of Calvary Cadets at [[Saint Petersburg]], receiving his commission in the hussars of the guard after graduation. By all accounts for the next several years he lived a dissolute life. His poetry was imitative of Pushkin and Byron. He also took a keen interest in Russian history and medieval epics, which would be reflected in ''[[the Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov]]'', his long poem ''Borodino'', poems addressed to the city of [[Moscow]], and a series of popular [[ballads]]. | |

==Fame and exile== | ==Fame and exile== | ||

| − | To his own and the nation's anger at the loss of Pushkin (1837) the young soldier gave vent in a passionate poem addressed to the [[Nicholas I of Russia|tsar]], | + | To his own and the nation's anger at the loss of Pushkin (1837) the young soldier gave vent in a passionate poem addressed to the [[Nicholas I of Russia|tsar]], entitled the "Death of a Poet." The poem proclaimed that, if Russia took no vengeance on the assassin of her poet, no second poet would be given her, (while demonstrating that such a poet had, indeed, arrived.) The poem all but accused the powerful "pillars" of Russian high society of complicity in Pushkin's murder. Without mincing words, it portrayed this society as a cabal of venal and venomous wretches "huddling about the Throne in a greedy throng", "the hangmen who kill liberty, genius, and glory" about to suffer the apocalyptic judgement of God. The Tsar, not surprisingly, responded to this insult by having Lermontov court-marshalled and sent to a regiment in the Caucausus. |

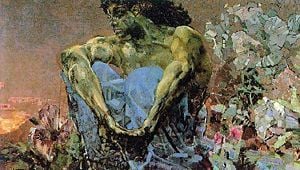

[[Image:Lerm Dagestan.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Lermontov took delight in painting mountain landscapes]] | [[Image:Lerm Dagestan.jpg|thumb|left|250px|Lermontov took delight in painting mountain landscapes]] | ||

| − | + | This punishment returned him to the place that he had first visited with his grandmother as a boy of ten. It was in that stern and rocky landscape of the Caucausus mountains that he found his own native land. | |

| − | Lermontov visited Saint Petersburg in [[1838]] and [[1839]] | + | Lermontov visited Saint Petersburg in [[1838]] and [[1839]]. His indignant observations of the aristocratic milieu, where he was welcomed by fashionable ladies as a kind of celebrity occassioned his play ''Masquerade''. His unreciprocated attachment to Varvara Lopukhina was recorded in the novel ''Princess Ligovskaya'', which he never finished. His duel with a son of the French ambassador led to his being returned to the Caucasian army, where he distinguished himself in the hand-to-hand fighting near the Valerik River. |

By 1839 he completed his only full-scale [[novel]], ''[[A Hero of Our Time]]'', which prophetically describes the [[duel]] in which he lost his life in July [[1841]]. In this contest he had purposely selected the edge of a precipice, so that if either combatant was wounded so as to fall his fate should be sealed. Much of his best verse was posthumously discovered in his pocket-book. | By 1839 he completed his only full-scale [[novel]], ''[[A Hero of Our Time]]'', which prophetically describes the [[duel]] in which he lost his life in July [[1841]]. In this contest he had purposely selected the edge of a precipice, so that if either combatant was wounded so as to fall his fate should be sealed. Much of his best verse was posthumously discovered in his pocket-book. | ||

Revision as of 11:07, 13 November 2005

Editing Mikhail Lermontov From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Jump to: navigation, search

Mikhail Yur'yevich Lermontov (Михаил Юрьевич Лермонтов), (October 15, 1814–July 27, 1841), a Russian Romantic writer and poet, sometimes called "the poet of the Caucasus", was the most important presence in the Russian poetry from Alexander Pushkin's death until his own four years later, at the age of 26 - like Pushkin, the casualty of a duel. In one of his best-known poems, written on January 1, 1840 he described his intonations as "iron verse steeped in bitterness and hatred."

Early life

Lermontov was born in Moscow to a respectable family of the Tula government, and grew up in the village of Tarkhany (in the Penza government), which now preserves his remains. His family traced descent from the Scottish Learmounts, one of whom settled in Russia in the early 17th century, during the reign of Michael Fedorovich Romanov.

The family estate of Lermontov's father was much more modest than his mother's, so his father, Yuri Lermontov, like his father before him, entered military service. Having moved up the ranks of captain, he married the sixteen year old Mariya Arsenyeva, to the great dismay of her mother, Elizabeth Alekseevna. A year later after the marriage, on the night of October 3rd, 1814, Mariya Arsenieva gave birth to Mikhail Lermontov. Tension between Yuri and his maternal grandmother persisted. Soon after, Mariya Arsenieva fell ill and died in 1817 soon after Lermontov' birth. After her daughter's death, Elizabeth Alekseevna devoted all her care and attention to the child and his education, all the time fearing that his father might sooner or later run off with him. In this environment of his grandmother's pampering and continuing family tension, Lermontov developed into a precocious, sensitive youth with a fearful temper, which he proceeded to take out on the servants and the bushes in his grandmother's garden.

The intellectual atmosphere in which he was raised differed little from that of Pushkin, though the domination of French, the language of the Russian aristocracy, receded in favor of a growing interest in English, while Lamartine shared his interest with Byron. In his early childhood Lermontov was educated by a certain Frenchman named Gendrot; but Gendrot was a poor pedagogue, so Elizabeth Alekseevna decided to take Lermontov to Moscow to prepare him better for the gymnasium. In Moscow, Lermontov was introduced to Goethe and Schiller by a German pedagogue, Levy, and a short time after, in 1828, he entered the gymnasium. He showed himself to be an incredibly talented student, once completely stealing the show at an exam by, first, impeccably reciting some poetry, and second, successfully performing a violin piece. At the gymnasium he also became acquainted with the poetry of Pushkin and Zhukovsky, and one of his friends, Catherine Hvostovaya, later described him as "married to a hefty volume of Byron". This friend had at one time been an object of Lermontov's affection, and to her he dedicated some of his earliest poems, one of the most remarkable ones being "Нищий (У врат обители святой)" (The Beggar). At that time, together with Lermontov's poetic passion, there also awoke an inclination for poisonous wit and cruel and sardonic humor. His ability to draw caricatures was matched by his ability to shoot someone down with a well aimed epigram or nickname.

After the academic gymnasium Lermontov entered Moscow University in August of 1830. That same summer the final, tragic act of the family discord played out. Having been struck deep by his son's alienation, Yuri Lermontov left the Arseniev house for good, only to die a short time later. His father's death was a terrible loss for Lermontov, as is evidenced by a few of his poems: "Forgive me, Will we Meet Again?" and "The Terrible Fate of Father and Son".

Lermontov's career at the University was very abrupt. He spent two years there but received no degree. While there, he was remembered for his aloofness and arrogant disposition; he attended the lectures rather faithfully, often reading a book in the corner of the auditorium, but rarely took part in student life.

Like his father before him, he decided to enter the military. From 1832 to 1834 he attended the School of Calvary Cadets at Saint Petersburg, receiving his commission in the hussars of the guard after graduation. By all accounts for the next several years he lived a dissolute life. His poetry was imitative of Pushkin and Byron. He also took a keen interest in Russian history and medieval epics, which would be reflected in the Song of the Merchant Kalashnikov, his long poem Borodino, poems addressed to the city of Moscow, and a series of popular ballads.

Fame and exile

To his own and the nation's anger at the loss of Pushkin (1837) the young soldier gave vent in a passionate poem addressed to the tsar, entitled the "Death of a Poet." The poem proclaimed that, if Russia took no vengeance on the assassin of her poet, no second poet would be given her, (while demonstrating that such a poet had, indeed, arrived.) The poem all but accused the powerful "pillars" of Russian high society of complicity in Pushkin's murder. Without mincing words, it portrayed this society as a cabal of venal and venomous wretches "huddling about the Throne in a greedy throng", "the hangmen who kill liberty, genius, and glory" about to suffer the apocalyptic judgement of God. The Tsar, not surprisingly, responded to this insult by having Lermontov court-marshalled and sent to a regiment in the Caucausus.

This punishment returned him to the place that he had first visited with his grandmother as a boy of ten. It was in that stern and rocky landscape of the Caucausus mountains that he found his own native land.

Lermontov visited Saint Petersburg in 1838 and 1839. His indignant observations of the aristocratic milieu, where he was welcomed by fashionable ladies as a kind of celebrity occassioned his play Masquerade. His unreciprocated attachment to Varvara Lopukhina was recorded in the novel Princess Ligovskaya, which he never finished. His duel with a son of the French ambassador led to his being returned to the Caucasian army, where he distinguished himself in the hand-to-hand fighting near the Valerik River.

By 1839 he completed his only full-scale novel, A Hero of Our Time, which prophetically describes the duel in which he lost his life in July 1841. In this contest he had purposely selected the edge of a precipice, so that if either combatant was wounded so as to fall his fate should be sealed. Much of his best verse was posthumously discovered in his pocket-book.

Works

During his lifetime, Lermontov published only one slender collection of poems (1840). Three volumes, much mutilated by the censorship, were issued a year after his death. His short poems range from indignantly patriotic pieces like Fatherland to the pantheistic glorification of living nature (e.g., I Go Out to the Road Alone...) Lermontov's early verse has been accused of puerility, for, despite his dexterious command of the language, it usually appeals more to adolescents than to adults. But that typically Romantic air of disenchantment was an illusion of which he was too conscious himself. Quite unlike Shelley, with whom he is often compared, he attempted to analyse and bring to light the deepest reasons for this metaphysical discontent with society and himself (e.g., It's Boring and Sad...)

Both patriotic and pantheistic veins in his poetry had incalculable repercussions throughout later Russian literature. Boris Pasternak, for instance, dedicated his 1917 poetic collection of signal importance to the memory of Lermontov's Demon. Such was the name of a long poem, featuring some of the most mellifluent lines in the language, which Lermontov rewrote upon a number of occassions, until his very death. The poem, which celebrates carnal passions of the "eternal spirit of atheism" to a "maid of mountains", was banned from publication for decades. Anton Rubinstein's lush opera on the same subject was also banned by censors who deemed it sacrilegious.

On account of his only novel, Lermontov should be considered one of the founding fathers of the Russian prose. A Hero of Our Time is actually a tightly knitted collection of short stories revolving around a single character, Pechorin. Short stories are intricately connected, so that a reader could follow from a superficial glimpse of the character's actions to understanding his philosophy and secret springs of seemingly mysterious behavior. The innovative structure of the novel inspired several imitations, notably by Vladimir Nabokov in his novel Pnin (1955).

See also

- Mikhail Lermontov (ship)

External links

Lermontov's poem

- The Dream is one of Lermontov's last poems, featured in his posthumous diary. Nabokov, whose translation follows, thought this "threefold dream" prophetic of the poet's own death.

- In noon's heat, in a dale of Dagestan

- With lead inside my breast, stirless I lay;

- The deep wound still smoked on; my blood

- Kept trickling drop by drop away.

- On the dale's sand alone I lay. The cliffs

- Crowded around in ledges steep,

- And the sun scorched their tawny tops

- And scorched me — but I slept death's sleep.

- And in a dream I saw an evening feast

- That in my native land with bright lights shone;

- Among young women crowned with flowers,

- A merry talk concerning me went on.

- But in the merry talk not joining,

- One of them sat there lost in thought,

- And in a melancholy dream

- Her young soul was immersed — God knows by what.

- And of a dale in Dagestan she dreamt;

- In that dale lay the corpse of one she knew;

- Within his breast a smoking wound shewed black,

- And blood coursed in a stream that colder grew.

Quotes

- O vanity! you are the lever by means of which Archimedes wished to lift the earth!

- Happy people are ignoramuses and glory is nothing else but success, and to achieve it one only has to be cunning.

- Exchange I would for one short day,

- For less, for but one hour amid

- The jagged rocks where play I did,

- A child, if 'twere but offered me,

- Both Heaven and eternity!

cs:Michail Jurjevič Lermontov de:Michail Jurjewitsch Lermontow es:Mijaíl Lermontov fr:Mikhaïl Lermontov hr:Mihail Jurjevič Ljermontov it:Mikhail Yuryevich Lermontov he:מיכאיל לרמונטוב ka:ლერმონტოვი, მიხეილ nl:Michail Lermontov ja:ミハイル・ユーリエヴィチ・レールモントフ ru:Лермонтов, Михаил Юрьевич sv:Michail Lermontov

Edit summary:

Cancel | Editing help (opens in new window)

Insert: Á á É é Í í Ó ó Ú ú À à È è Ì ì Ò ò Ù ù  â Ê ê Î î Ô ô Û û Ä ä Ë ë Ï ï Ö ö Ü ü ß Ã ã Ñ ñ Õ õ Ç ç Ģ ģ Ķ ķ Ļ ļ Ņ ņ Ŗ ŗ Ş ş Ţ ţ Ć ć Ĺ ĺ Ń ń Ŕ ŕ Ś ś Ý ý Ź ź Đ đ Ů ů Č č Ď ď Ľ ľ Ň ň Ř ř Š š Ť ť Ž ž Ǎ ǎ Ě ě Ǐ ǐ Ǒ ǒ Ǔ ǔ Ā ā Ē ē Ī ī Ō ō Ū ū ǖ ǘ ǚ ǜ Ĉ ĉ Ĝ ĝ Ĥ ĥ Ĵ ĵ Ŝ ŝ Ŵ ŵ Ŷ ŷ Ă ă Ğ ğ Ŭ ŭ Ċ ċ Ė ė Ġ ġ İ ı Ż ż Ą ą Ę ę Į į Ų ų Ł ł Ő ő Ű ű Ŀ ŀ Ħ ħ Ð ð Þ þ Œ œ Æ æ Ø ø Å å Ə ə – — … [] [[]] {{}} ~ | ° § → ≈ ± − × ¹ ² ³ ‘ “ ’ ” £ € Α α Β β Γ γ Δ δ Ε ε Ζ ζ Η η Θ θ Ι ι Κ κ Λ λ Μ μ Ν ν Ξ ξ Ο ο Π π Ρ ρ Σ σ ς Τ τ Υ υ Φ φ Χ χ Ψ ψ Ω ω

Your changes will be visible immediately. For testing, please use the sandbox. You're encouraged to create and improve articles. The community is quick to enforce the quality standards on every article you edit. Please cite your sources so others can check your work. On discussion pages, please sign your comment by typing four tildes (David Burgess 01:08, 6 November 2005 (UTC)).

DO NOT SUBMIT COPYRIGHTED WORK WITHOUT PERMISSION All edits are released under the GFDL (see WP:Copyrights). If you don't want your writing to be edited and redistributed by others, do not submit it. Only public domain resources can be copied exactly—this does not include most web pages.

Retrieved from "http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mikhail_Lermontov"

ViewsArticleDiscussionEdit this pageHistory Personal toolsCreate account / log in Navigation

Main PageCommunity PortalCurrent eventsRecent changesRandom articleHelpContact usDonations

Search

Toolbox

What links here Related changes Upload file Special pages

About Wikipedia Disclaimers

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.