Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "Melanie Klein" - New World

| Line 61: | Line 61: | ||

Alford, C.F. (1990). ''Melanie Klein and Critical Social Theory: An Account of Politics, Art, and Reason Based on Her Psychoanalytic Theory''. Yale University Press | Alford, C.F. (1990). ''Melanie Klein and Critical Social Theory: An Account of Politics, Art, and Reason Based on Her Psychoanalytic Theory''. Yale University Press | ||

| − | Bion, W. ( | + | Bion, W. (1991). ''Experiences in Groups''. Routledge. ISBN 0415040205 |

Grosskurth, P. (1987). ''Melanie Klein: Her World and Her Work'', Karnac Books | Grosskurth, P. (1987). ''Melanie Klein: Her World and Her Work'', Karnac Books | ||

| − | Hinshelwood, R | + | Hinshelwood, R. (2003). ''Introducing Melanie Klein'' (2nd Ed.), Totem Books. ISBN 1840460695 |

| − | Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. In Money-Kyrle, R., Joseph, B., O'Shaughnessy, E. & Segal, H. (Eds.).(1984). The writings of Melanie Klein. Vol III. London: The Hogarth Press. | + | Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. In Money-Kyrle, R., Joseph, B., O'Shaughnessy, E. & Segal, H. (Eds.).(1984). ''The writings of Melanie Klein. Vol III''. London: The Hogarth Press. |

| − | Klein, M. (2002). | + | Klein, M. (2002). ''Love, Guilt and Reparation: And Other Works 1921-1945''. Free Press. ISBN 074323765X |

| − | Likierman, M. (2002). | + | Likierman, M. (2002). ''Melanie Klein, Her Work in Context.'' Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826457703 |

| − | Ogden, T.H. (1979), On projective indentification. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 60: 357-373. | + | Ogden, T.H. (1979), On projective indentification. ''International Journal of Psycho-Analysis'', 60: 357-373. |

| − | Ogden, T. (1986). The Matrix of the Mind. Object Relations Theory and the Psychoanalytic Dialogue. Northwale, NJ: Jason Aronson. | + | Ogden, T. (1986). The Matrix of the Mind. Object Relations Theory and the Psychoanalytic Dialogue. Northwale, NJ: Jason Aronson. ISBN 1568210515 |

| − | Rose, J. (1993). ''Why War? - Psychoanalysis, Politics, and the Return to Melanie Klein''. Blackwell Publishers | + | Rose, J. (1993). ''Why War? - Psychoanalysis, Politics, and the Return to Melanie Klein''. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0631189246 |

| − | Spillius, E.B.(1988) Melanie Klein Today | + | Spillius, E.B.(1988). ''Melanie Klein Today''. (2 Volumes.). Routledge. ISBN 0415006767 & ISBN 0415010454 |

== External Links == | == External Links == | ||

Revision as of 19:18, 8 April 2006

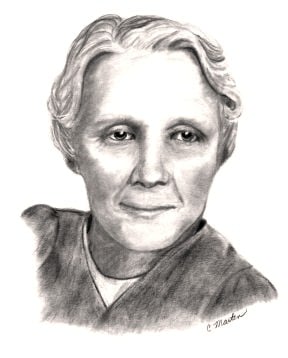

Melanie Klein, (born March 30, 1882 – died September 22, 1960), was an Austrian psychotherapist, who building upon the classic psychoanalytic theory, constructed therapeutic techniques for children that influenced development of present methods of child care and rearing.

Life

Melanie Klein was born in Vienna, in 1882. Her father, Dr. Moriz Reisez, was a successful physician. He rebelled against his family’s wishes to become a rabbi, and instead finished a medical school, and opened a private practice. He married at the age of 40 to Libusa Deutsch, who bore him four children, Melanie being the youngest one. Klein had a happy childhood, mixed with search for knowledge and art. Klein’s father died when she was 18. Despite being Jewish, religion played little role in Klein’s life. She has always labeled herself as an atheist. However, she has never forgotten her roots, and frequently appealed to parents to teach their children religion according to their own beliefs.

Klein had a very close relationship with her siblings, especially Emmanuel and Sidonie. Emmanuel was her older brother who tutored Klein in Greek and Latin, and who introduced her to the intellectual circles of Vienna. Klein’s sister Sidonie, on the other side, thought Klein to read and write. Both siblings left mark on Klein’s early life, and when they both prematurely died, Klein became seriously depressed, something that will be a characteristics of the personality throughout her whole life.

Klein married to Arthur Klein, a friend of her father. He was an engineer, and had to travel a lot as part of his job. Klein followed her husband wherever he went, but as the result, Klein could never finish any academic degree, although she had aspirations to go to a medical school. Instead, Klein studied languages and read books. Later in her career, Klein regretted not being able to complete a degree, as she was often not respected in the academic circled due to her lack of credentials. She bore two children – Melitta in 1904, and Hans in 1907.

Klein’s family moved to Budapest in 1910, where she met first time with the work of Sigmund Freud. From that year on, she dedicated her whole time to study psychoanalysis. She became especially interested in studying children. Klein met Freud in 1917, and wrote her first paper The Development of a Child, in 1919. The same year she became a member of the Budapest Psychoanalytic Society. After her husband received a job in Sweden, Klein moved her children to Slovakia, and decided to file for a divorce. In 1922 the divorce was final.

In 1921 Klein met Karl Abraham, who inspired her to continue to work with children. She moved to Berlin, Germany, where she opened a psychoanalytic practice for both children and adults. She especially focused on the work with emotionally disturbed children and continued with this practice until 1926. However, as psychoanalytic school in Germany developed, it also became somewhat differentiated from other schools in the other parts of Europe. Different psychoanalysts developed and used different techniques in their practice. When Anna Freud started her own work with children, it became obvious that Klein’s approach differed from that of Anna Freud, and Klein was slowly pushed out of Berlin’s academic circles. Thus in 1927, together with her children, Klein moved to England. She gave series of lectures in London, and was warmly welcomed. She became a member of the British Psychoanalytic Society, and soon opened a private practice. In England she developed her ideas on death instinct and Oedipus complex. She remained in England until her death in 1960.

Work

Klein's theoretical work gradually centered on a highly speculative hypothesis proposed by Freud, which stated that life is an anomaly – that it is drawn toward an inorganic state, and therefore, in an unspecified sense, contains an instinct to die. In psychological terms, Eros - the sustaining and uniting principle of life - is postulated to have a counterpart force – Thanatos, which seeks to terminate and disintegrate life.

Examining ultra-aggressive fantasies of hate, envy, and greed in very young and very ill children, Klein put forth the interpretation that the human psyche is in a constant oscillation depending on whether Eros or Thanatos is in the fore. She calls the state of the psyche, when the sustaining principle of life is in domination, the depressive position. The psychological state corresponding to the disintegrating tendency of life she gives the name the paranoid-schizoid position.

Klein's insistence on regarding aggression as an important force in its own right, when analyzing children, brought her into conflict with Anna Freud, the other major child psychotherapist working at the time. Many controversies arose from this conflict.

Some major ideas important for Klein’s work are described below:

Object Relations Theory Object relations theory is the idea, developed by Sigmund Freud, W.R.D. Fairbairn, and Melanie Klein, that the ego-self exists only in relation to other object, which may be external or internal. The internal objects are internalized versions of external objects, primarily formed from early interactions with the parents. In another words, a child’s first object of desire is his caregiver, for child can only satisfy its needs through that object. The relationship between a child and a caregiver, and the way child satisfies his needs is eventually internalized into mental representations. There are three fundamental mental representations that can exist between the self and the other - attachment, frustration, and rejection. These representations are universal emotional states, and are major building blocks of personality. The central thesis in Melanie Klein's object relations theory was that the objects can be either part-object or whole-object, i.e. a single organ (a mother's breast) or a whole person (a mother). Both a mother or just a mother's breast can be the locus of satisfaction for a drive. According to traditional psychoanalysis, there are at least two types of drives, the libido (mythical counterpart: Eros), and the death drive (mythical counterpart: Thanatos). Thus, the object can be a receiver of both love and hate – the affective nature of the libido or the death drive. Depending on the nature of the relationship between a child and a caregiver, child can develop various disturbances, as an excessive preoccupation with certain body parts or preoccupation with parts versus a whole person.

Object relations theory was further developed in the 1940's and 50's by British psychologists Ronald Fairbairn, D.W. Winnicott, Harry Guntrip, and others. Recent decades in developmental psychological research, for example, on the onset of a Theory of Mind (understanding that others have minds with separate beliefs, desires and intentions) in children, have found that the formation of mental world is enabled by the infant-parent interpersonal interaction, which was the main thesis of British object-relations tradition (e.g. Fairbairn, 1952).

Projective Identification Projective identification is a psychological term that was first introduced by Melanie Klein in 1946. It refers to a psychological process in which a person projects thoughts or beliefs that they have onto a second person. Then, in most common definitions of projective identification, there is an action in which the second person is changed by the projection and begins to behave as though he or she is in fact actually characterized by those thoughts or beliefs that have been projected. This is a process that generally happens outside of the conscious awareness of both parties involved (although this has been debated).

The content of projection is often an intolerable, painful, or dangerous idea or belief about the self, which person simply cannot tolerate (i.e. "I have behaved wrongly" or "I have a sexual feeling towards ...." ). The first person “projects” that content to somebody else, “outside” of his/her own person. The recipient of the projection then processes or "metabolizes" the projection and internalizes it.

Projective identification is believed to be a very early or primitive psychological process and is understood to be one of the more primitive defense mechanisms. Yet is also thought to be the basis out of which more mature psychological processes like empathy and intuition are formed.

Here is a simple example of projective identification in a psychiatric setting. A traumatized patient describes to his analyst a horrible incident, which he experienced recently. Yet in describing this incident the patient remains emotionally unaffected or even indifferent to his own obvious suffering and perhaps even the suffering of his loved ones. When asked he denies having any feelings about the event whatsoever. Yet, when the analyst hears this story, she begins to feel very strong feelings (i.e. perhaps sadness and/or anger) in response. She might tear up or become righteously indignant on behalf of the patient, thereby acting out the patient's feelings resulting from the trauma. Being a well-trained analyst however, she recognizes the profound effect that her patient's story is having on her. Acknowledging to herself the feelings she is having, she suggests to the patient that he might perhaps be having feelings that are difficult for him to experience in relation to the trauma. She processes or metabolizes these experiences in herself and puts them into words and speaks them to the patient. Ideally, then the patient can recognize in himself the emotions or thoughts that he previously could not let into his awareness.

The Play Therapy Klein developed the technique of play therapy that is still used worldwide. Building on Freud’s method of free associations, Klein believed that, since children cannot express themselves through associations, they could through play and art. In another words, children project their feelings through play and drawings. Their unconscious fantasies and hidden emotions come out when they freely play, or do an artwork. Klein believed that therapist could use play to relieve negative, aggressive feelings in children, and such treat children from emotional disorders. Anna Freud, on the other side, believed that children couldn’t be analyzed, and thus she didn’t accept play therapy as valid. That was one of the main disagreements between Klein and Freud.

Legacy

Melanie Klein, together with Anna Freud, was the first to apply psychoanalytic theories to treat disorders in children. She developed play therapy, which is still widely used in practice. Her emphasis on early childhood experiences, as paramount in one’s life, has influenced many generations of psychologists to come.

Until the 1970s few American psychoanalysts were influenced by the school of Melanie Klein, on the one hand, who constituted an opposite polarity to the school of Anna Freud (which dominated American psychoanalysis in 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s and was represented in the US by Hartmann, Kris, Loewenstein, Rapaport, Erikson, Jacobson, and Mahler), and, on the other hand, the "middle group" who fell between Anna Freud and Melanie Klein, and was influenced by the British schools of Michael Balint, Donald Winnicott, and Ronald Fairbairn. The strong animosity in England between the school of Anna Freud and that of Melanie Klein was transplanted to the US, where the Anna Freud group dominated totally until the 1970s, when new interpersonal psychoanalysis arose partly from ideas of culturalist psychoanalysis, influenced also by Ego psychology, and partly by British theories which have also entered under the broad terminology of "British object relations theories".

She founded the Melanie Klein Trust in 1955 to promote research and training in methods developed by Klein.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

Alford, C.F. (1990). Melanie Klein and Critical Social Theory: An Account of Politics, Art, and Reason Based on Her Psychoanalytic Theory. Yale University Press

Bion, W. (1991). Experiences in Groups. Routledge. ISBN 0415040205

Grosskurth, P. (1987). Melanie Klein: Her World and Her Work, Karnac Books

Hinshelwood, R. (2003). Introducing Melanie Klein (2nd Ed.), Totem Books. ISBN 1840460695

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. In Money-Kyrle, R., Joseph, B., O'Shaughnessy, E. & Segal, H. (Eds.).(1984). The writings of Melanie Klein. Vol III. London: The Hogarth Press.

Klein, M. (2002). Love, Guilt and Reparation: And Other Works 1921-1945. Free Press. ISBN 074323765X

Likierman, M. (2002). Melanie Klein, Her Work in Context. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0826457703

Ogden, T.H. (1979), On projective indentification. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 60: 357-373.

Ogden, T. (1986). The Matrix of the Mind. Object Relations Theory and the Psychoanalytic Dialogue. Northwale, NJ: Jason Aronson. ISBN 1568210515

Rose, J. (1993). Why War? - Psychoanalysis, Politics, and the Return to Melanie Klein. Blackwell Publishers. ISBN 0631189246

Spillius, E.B.(1988). Melanie Klein Today. (2 Volumes.). Routledge. ISBN 0415006767 & ISBN 0415010454

External Links

Melanie Klein official website

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.