Encyclopedia, Difference between revisions of "John Herschel" - New World

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

Peter Duveen (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

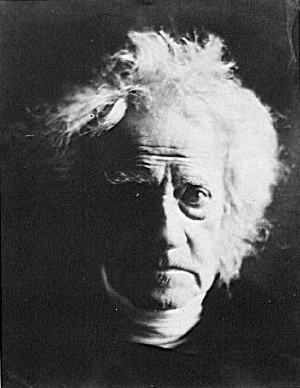

In 1867, the society photographer Julia Cameron was allowed to complete a series of portraits of Herschel, and these are among the best-know images of the scientist. It is said that she had the scientist's hair washed for the portraits, and she fashioned it in a way that radiated a feeling of the romantic that was reflective of the times. | In 1867, the society photographer Julia Cameron was allowed to complete a series of portraits of Herschel, and these are among the best-know images of the scientist. It is said that she had the scientist's hair washed for the portraits, and she fashioned it in a way that radiated a feeling of the romantic that was reflective of the times. | ||

| + | |||

| + | In Herschel's later years, he kept up a lively correspondence with his friends and with the scientific community up until the time of his death. He also continued his astronomical observations. But gout and bronchitis eventually took its toll as he entered his late 70s. Herschel also lamented the loss of his close friends such as Peacock that passed away before he did. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On May 11, 1871, he died in his home in Collingwood. | ||

==General== | ==General== | ||

Revision as of 04:05, 18 July 2007

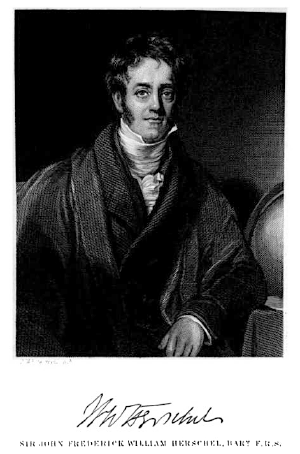

Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet KH (March 7, 1792–May 11, 1871) was an English mathematician, astronomer, chemist, and experimental photographer/inventor, and the son of astronomer William Herschel. He published several star catalogs based on his own observations, and contributed to the development of photography when it first emerged in 1839. Herschel believed that the study of nature was an avenue to the understanding of God's creation, and was supportive of the design theories of Charles Babbage.

Early life and work on astronomy

Left handed and right handed xtals 1825-33 astronomical observations in 1825, he decided to study nebulae, indicating that "nobody else could see them." More than 2300 nebulae and star clusters. 1826, two papers on andromeda and Orion Nebula, and began double star catalog, about 5000 objects, compared to 850 of his father.

Herschel was born in Slough, Buckinghamshire, the son of William and Mary Herschel. Herschel's father was a world-famous astronomer who had discovered the planet Uranus in 1881, and who continued to make many contributions to astronomy and physics until his death in 1822. When Herschel was seven, he was briefly enrolled at a boarding school at Eaton, but his mother feared the rough treatment he endured there at the hands of the students. He was later placed in a local school, where he made more progress, particularly in languages, although he lagged somewhat in mathematics, not demonstrating an innate proficiency in the subject at that early age. He later studied at Eton College and St John's College, Cambridge. He graduated as senior wrangler in 1813.[2] It was during his time as an undergraduate, that he became friends with Charles Babbage and George Peacock.[2] In 1813, he became a fellow of the Royal Society of London after submitting a mathematics memoir. Herschel, Babbage and Peacock established a group called the Analytical Society, which championed the introduction into Great Britain of mathematical methods and notation deveoloped on the continent. The group was formed in reaction to the perception that science in England was on the decline. The three translated a popular calculus text used in France, and by 1820, the continental style had taken firm root in Britain. Herschel contibuted a volume devoted to the calculus of finite differences in a two volume work that the society published in 1820.

However, inspired by the work of Henry Hyde Wollaston and David Brewster, Herschel gradually returned to the family tradition of studying astronomy that had been established by Herschel's father and his aunt Caroline. he took up astronomy, assisting his father and building telescopes. In 1819, he reported discovering sodium thiosulphate and its ability to dissolve silver salts. This property would later be used in photography to fix photographic plates.

In 1821 the Royal Society bestowed upon him the Copley Medal for his mathematical contributions to their Transactions. In the same year, accompanied by Babbage, Herschel took a tour of Europe, one of three such excursions he would make a space of four years. Herschel and Babbage spent much of time in the Alps taking measurements and making observations. During a stopover in Paris, they met the naturalist and world traveler Alexander von Humboldt. Von Humboldt would become a lifelong friend of Herschel, and the two would later work together to improve the new science of photography. Between 1821 and 1823 Herschel re-examined, with James South, the double stars catalogued by his father, and added observations of his own, thus expanding the list of double stars from 850 to 5,075. For this work he was presented in 1826 with the Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society (which he won again in 1836), and with the Lalande Medal of the French Institute in 1825, while He was made a Knight of the Royal Guelphic Order in 1831.[2]

Visit to South Africa

In 1830, Herschel was a candidate for the presidency of the Royal Society of London, but the Duke of Sussex, King George III's son, won the election, after which Herschel's group gradually distanced itself from the society. In 1833, Herschel published "A Treatise on Astronomy. In the same year, the death of his mother and his waning enthusiasm for the activities of the Royal Society prompted Herschel to embark on a long-dreamed-of journey to South Africa to observe and catalog the stars and other celestial objects obvervable only from the Southern Hemisphere. [2] This was to be a completion as well as extension of the survey of the northern heavens undertaken initially by his father William Herschel. He arrived in Cape Town on 15 January 1834. Amongst his other observations during this time was that of the return of Comet Halley.

However, in addition to his astronomical work, this voyage to a far corner of the British empire also gave Herschel an escape from the pressures under which he found himself in London, where he was one of the most sought-after of all British men of science. While in southern Africa, he engaged in a broad variety of scientific pursuits free from a sense of strong obligations to a larger scientific community. It was, he later recalled, probably the happiest time in his life.

Gradualist view of development

Intrigued by the ideas of gradual formation of landscapes set out in Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology, he wrote to Lyell commenting and urging a search for natural laws underlying the "mystery of mysteries" of how species formed, prefacing his words with the couplet:

- He that on such quest would go must know not fear or failing

- To coward soul or faithless heart the search were unavailing.

Taking a gradualist view of development, he commented

- "Time! Time! Time! — we must not impugn the Scripture Chronology, but we must interpret it in accordance with whatever shall appear on fair enquiry to be the truth for there cannot be two truths. And really there is scope enough: for the lives of the Patriarchs may as reasonably be extended to 5000 or 50000 years apiece as the days of Creation to as many thousand millions of years."

The document was circulated, and Charles Babbage incorporated extracts in his ninth and unofficial Bridgewater Treatise, which postulated laws set up by a divine programmer. When HMS Beagle called at Cape Town, Captain Robert FitzRoy and the young naturalist Charles Darwin visited Herschel on 3 June 1836. Later on, Darwin would be influenced by Herschel's writings in developing his theory advanced in The Origin of Species. In the opening lines of that work, Darwin writes that his intent is "to throw some light on the origin of species — that mystery of mysteries, as it has been called by one of our greatest philosophers," referring to Herschel.

Return to England

Upon Herschel's return to England after four years in Capetown, he was welcomed with a dinner attended by about 400 persons, including such notables as Michael Faraday, Charles Darwin, William Rowan Hamilton, Charles Lyell, Charles Babbage, William Whewell, and the antarctic explorer James Ross. In the same year, he was created a baronet[2]. He did not publish Results of Astronomical Observations made at the Cape of Good Hope until 1847. In this publication he proposed the names still used today for the seven then-known satellites of Saturn: Mimas, Enceladus, Tethys, Dione, Rhea, Titan, and Iapetus.[3] In the same year, Herschel received his second Copley Medal from the Royal Society for this work. A few years later, in 1852, he proposed the names still used today for the four then-known satellites of Uranus: Ariel, Umbriel, Titania, and Oberon.

Photography

Daguerre announced his invention of photography in 1839. That same year, Herschel developed his own process of fixing a photographic image, which differed from both Daguerre's and that of another pioneer of photography, Fox Talbot. However, Herschel refrained from publishing a complete account of his process, instead deferring to Talbot, as Herschel was unaware that his process differed from Talbot's. Herschel used paper to capture his images, a process which eventually overtook imagery on metal and glass. He discovered sodium thiosulfate to be a solvent of silver halides in 1819, and informed Talbot and Daguerre of his discovery that this "hyposulphite of soda" ("hypo") could be used as a photographic fixer, to "fix" pictures and make them permanent, after experimentally applying it.

He made numerous experiments on different chemical processes that could produce an image, including organic dyes such as are found in flowers, and recorded and published his results. He invented the cyanotype process and variations, the precursors of the modern blueprint process. He experimented with color reproduction, noting that rays of different parts of the spectrum tended to impart their own color to a photographic paper. He is often credited with coining the words "postive" and "negative," referring to images that reflect the normal and reverse shades in a photographic image. Most of Herschel's work in photography was accomplished between the years 1839 and 1844.

During this same period, he continued to process the data he gathered during his trip to Africa, a process that was time-consuming. He finally finished this grand task in 1847, and published his results.

In 1849, Herschel published Outlines of Astronomy, a popular exposition that went through many editions and was considered a must-read in intellectual circles in Britain, although the content was often chellenging even to educated minds.

In 1867, the society photographer Julia Cameron was allowed to complete a series of portraits of Herschel, and these are among the best-know images of the scientist. It is said that she had the scientist's hair washed for the portraits, and she fashioned it in a way that radiated a feeling of the romantic that was reflective of the times.

In Herschel's later years, he kept up a lively correspondence with his friends and with the scientific community up until the time of his death. He also continued his astronomical observations. But gout and bronchitis eventually took its toll as he entered his late 70s. Herschel also lamented the loss of his close friends such as Peacock that passed away before he did.

On May 11, 1871, he died in his home in Collingwood.

General

Herschel wrote many papers and articles, including entries on meteorology, physical geography, and the telescope for the eighth edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica.[2]

In 1835, the New York Sun newspaper wrote a series of satiric articles that came to be known as the Great Moon Hoax, with statements falsely attributed to Herschel about his supposed discoveries of animals living on the Moon, including batlike winged humanoids.

Herschel Island (in the Arctic Ocean, north of the Yukon Territory) and J. Herschel crater, on the Moon, are named after him.

Family

He married Margaret Brodie Stewart (1810-1864) on 3 March 1829. They had 12 children:

- Caroline Emilia Mary Herschel (1830-1909)

- Isabella Herschel (1831-1893)

- Sir William James Herschel, 2nd Bt. (1833-1917)

- Margaret Louisa Herschel (1834-1861), an accomplished artist

- Alexander Stewart Herschel (1836-1907)

- Colonel John Herschel (1837-1921)

- Maria Sophie Herschel (1839-1929)

- Amelia Herschel (1841-1926) married Sir Thomas Francis Wade, diplomat and sinologist

- Julia Mary Herschel (1842-1933)

- Matilda Rose Herschel (1844-1914)

- Francisca Herschel (1846-1932)

- Constance Ann Herschel (1855-1939)

On his death at Collingwood, his home near Hawkhurst in Kent, he was given a national funeral and buried in Westminster Abbey.

Legacy

John Herschel could have easily been overshadowed by his famous father, who, among his many accomplishments, discovered the planet Uranus. But instead, he first established his own reputation in mathematics before deciding to follow and expand upon his father's path. In his day, he was as legendary as his father, and was the personification of nineteenth century science, particularly in England. In real terms, he made substantial contributions to many fields, beyond his astronomical exploits. He always remained a firm believer in the divine. In his Preliminary Discourse on the Study of Natural Philosophy, he supported the association of nature with divine creation. This probably brought him into conflict with the theory of evolution proposed by Charles Darwin, although Darwin was quick to point out that Herschel sought to find an explanation for the emergence of species that Darwin's theory attempted to explain.

Publications

- On the Aberration of Compound Lenses and Object-Glasses (1821);[2]

- Outlines of Astronomy (1849);[2]

- General Catalogue of 10,300 Multiple and Double Stars (published posthumously);

- Familiar Lectures on Scientific Subjects;

- General Catalogue of Nebulae and Clusters;

- Manual of Scientific Inquiry (ed.), (1849);[2]

- Familiar Lectures on Scientific Subjects (1867).[2]

See also

Notes

- ↑ John Timbs, The Year-book of Facts in Science and Art, London: Simpkin, Marshall, and Co., 1846

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; no text was provided for refs namedHersNAH - ↑ "Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, volume 8, page 42" (archive), NASA, 2004, ADsabs.harvard.edu webpage: Adsabs-MNRAS.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

<<We need at least 3 references here, properly formatted.>>

- Ball, Robert S. 1895. Great astronomers. London: Isbister.

- Buttmann, Günther. 1974. The shadow of the telescope a biography of John Herschel; tr. by B. E. J. Pagel. Ed. and intro. by David S. Evans. Guildford: Lutterworth Press. ISBN 0718820878

- Ruskin, Steven, and John F. W. Herschel. 2004. John Herschel's Cape voyage: private science, public imagination, and the ambitions of empire. Burlington, VT: Ashgate. ISBN 0754635589.

External links

- http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/Mathematicians/Herschel.html

- Biography: JRASC 74 (1980) 203

- The Herschel Chronicle

- Photographic Process and Early Photograms

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.