James Reese Europe

James Reese Europe (22 February, 1881 – 9 May, 1919) was an American ragtime and early jazz bandleader, arranger, and composer. He was the leading figure on the African American music scene of New York City in the 1910s. Europe was born in Mobile, Alabama. His family moved to Washington, D.C. when he was 10 years old. He moved to New York in 1904.

In 1910 Europe organized the Clef Club, a society for African Americans in the music industry. In 1912, they made history when they played a concert at Carnegie Hall for the benefit of the Colored Music Settlement School. The Clef Club Orchestra was the first jazz band to play at Carnegie Hall. It is hard to overstate the importance of that event in the history of jazz in the United States. It was 12 years before the Paul Whiteman and George Gershwin concert at Aeolian Hall and 26 years(!) before Benny Goodman's famed concert at Carnegie Hall. In the words of Gunther Schuller, Reese "...had stormed the bastion of the white establishment and made many members of New York's cultural elite aware of Negro music for the first time." [1]

His "Society Orchestra" became nationally famous in 1912 accompanying theater headliner dancers Vernon Castle and Irene Castle. In 1913 and 1914 he made a series of phonograph records for the Victor Talking Machine Company. These recordings are some of the best examples of the pre-jazz hot ragtime style of the U.S. North-East of the 1910s. [2]

Neither the Clef Club Orchestra nor the Society Orchestra were small, what we would call "Dixeland" bands. They were large symphonic bands to satisfy the tastes of a public that was used to performances by the likes of the John Phillip Sousa band and simlar organizations very popular at the time. The Clef Orchestra had 125 members[3] and played on various occasions between 1912 ans 1915 in Carnegie Hall. It is instructive to read a comment from a music review in the New York Times from March 12 , 1914:

- "...the programme consisted largely of plantation medlodies and spirituals ...{arranged such as to show that]...these composers are beginning to develop an art of their own based on their folk material..." [4]

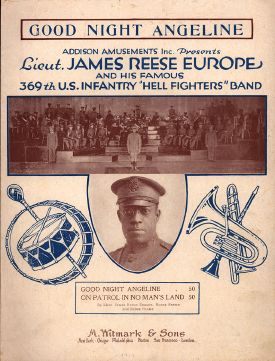

During World War I Europe obtained a Commission in the New York Army National Guard, where he saw combat as a lieutenant with the 369th Infantry Regiment (the "Harlem Hellfighters"), the band of which he directed to great acclaim. In February and March of 1918, James Reese Europe and his military band travelled over 2,000 miles in France, performing for British, French and American military audiences as well as French civilians. [5] The first concert included a French march, and the Stars and Stripes Forever as well as syncopated numbers such as "The Memphis Blues", which, according to a later description of the concert by a band member "...started ragtimitis in France". [6]

The band returned to the U.S.A. in February of 1919. That year he made more recordings for Pathé Records. These include both instrumentals and accompanyments to vocalist Noble Sissle. The style is significantly changed from Europe's recordings of a few years earlier, incorporating blues, blue notes, and early jazz influence (including a rather stiff cover record of the Original Dixieland Jass Band's "Clarinet Marmalade").

There is a popular perception that jazz left New Orleans in 1917 when the US Navy put the Storyville section of the city off-limits, thus putting the many musicians who played in those establishments out of work and, thus, causing a great "diaspora" of those who would then spread jazz music throughout the rest of the United States. That view is , at the very least, an oversimplification. New Orleans musicians such as the Original Creole Orchestra were already in New York years earlier. The syncopations and unique melodic concepts ("blue notes", etc.) of jazz were present in many other places—including New York City—quite a few years earlier.

James Reese Europe died after being stabbed by a member of his band. At the time of his death, he was the best-known African American bandleader in the United States.

references and further reading

- Badger, F. Reed (1995). A Life in Ragtime: A Biography of James Reese Europe. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-506044-X.

- Badger, F. Reed (Spring, 1989). James Reese Europe and the Prehistory of Jazz. American Music 7 (1): 48-67. ISSN 0734-4392.

- Logan, Rayford W. and Michael R. Winston. (1983). "Europe, James Reese". Dictionary of American Negro Biography. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0-393-01513-0.

- Walton, Lester A. et al (Spring, 1978). Black-Music Concerts in Carnegie Hall, 1912-1915. The Black Perspective in Music 6 (1): 71-88. ISSN 0090-7790.

- Welburn, Ron (1987). James Reese Europe and the Infancy of Jazz Criticism. Black Music Research Journal 7: 35-44. ISSN 0276-3605.

- Wilson, Olly (Winter, 1986). The Black-American Composer and the Orchestra in the Twentieth Century. The Black Perspective in Music 14 (1 Special Issue: Black American Music Symposium): 26-34. ISSN 0090-7790.

notes

External links

- James Reese Europe on Jass.com Article with images

- Europe's Society Orchestra Article and audio of the 1913–1914 recordings on redhotjazz.com

- Jim Europe's 369th Infantry "Hellfighters" Band Article and audio of the 1919 recordings on redhotjazz.com

- Songs Brought Back from the Battlefield

- University of Michigan Exhibition

- From Ken Burns film, Jazz.

- An on-line discography

[[Category:Music]