de Cordemoy, Géraud

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (import from wiki) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) m |

||

| (17 intermediate revisions by 8 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{copyedited}} |

| − | {{ | + | {{epname|de Cordemoy, Géraud}} |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

[[Image:geraud_de_cordemoy.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Portrait of Géraud de Cordemoy in the 1704 edition of the complete works]] | [[Image:geraud_de_cordemoy.jpg|thumb|200px|right|Portrait of Géraud de Cordemoy in the 1704 edition of the complete works]] | ||

| − | + | '''Géraud de Cordemoy,''' (October 6, 1626 - October 15, 1684) was a [[France|French]] [[philosophy|philosopher]], historian, and lawyer, known for his works in [[metaphysics]] and for his [[philosophy of language|theory of language]]. Though a lawyer by profession, Cordemoy was a prominent figure in Parisian philosophical circles. He was one of the early Cartesian philosophers, active during the decades immediately following the death of [[Descartes]]. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | Géraud de Cordemoy | ||

| − | |||

| + | His major works include ''Le Discernement du corps et de l'âme'' (''The Differentiation of the Body and the Soul,'' 1666), in which he incorporated [[atomism]] into a Cartesian mechanistic system, and pointed out that the two elements of mind and body in any human being often fail to correspond with each other. Along with [[Arnold Geulincx]] and Louis de Laforge, he developed [[occasionalism]], the doctrine that body and soul were essentially and causally distinct and that it was only God who allowed a person’s will to move his physical body, or a person’s mind to experience sensations originating from the physical body. The same was true for every “body,” or entity, in the universe; therefore, God was the real and universal cause of every movement. ''Le Traité physique de la parole (A Physical Treatise on Speech,'' 1668) suggested that human’s ability to use words as vehicles of thought demonstrated the existence of a rational soul. | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Cordemoy accepted the [[ontology|ontological]] framework of Descartes, who identified body with extension and mind with thought. His acceptance of Descartes' framework limited philosophical paths he could take. While his occasionalism left a perspective in the history of modern philosophy, later thinkers questioned validity of Descartes' presuppositions themselves. | ||

| − | == | + | ==Life== |

| + | Géraud de Cordemoy was born October 6, 1626, to a family of ancient nobility originating from Auvergne (from the town of Royat) in [[France]]. He was the only son, and the third of four children, of Géraud and Nicole de Cordemoy. His father was a master in arts at the [[University of Paris]], and died when Géraud was nine years old. Little is known about his early years or his education. He married Marie de Chazelles, and the birth of the first of his five children is recorded on December 7, 1651. | ||

| − | + | Géraud was a private tutor and [[linguistics|linguist]] and practiced as a lawyer. He associated with the philosophical circles of [[Paris]], attending various salons, and made the acquaintance of Emmanuel Maignan and the physicist Jacques Rohault. He was a friend and a protégé of Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, a French bishop and orator who also admired [[Descartes]]. Géraud de Cordemoy was appointed tutor for the Dauphin, son of King [[Louis XIV]], at the same time as Fléchier, and was elected a member of the Académie Française in 1675, where he served briefly as director. He died, after a brief illness, on October 15, 1684. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | == | + | ==Thought and works == |

| − | + | Géraud de Cordemoy was one of the early and more important Cartesian philosophers, active during the decades immediately following the death of [[Descartes]]. | |

| − | + | In 1664, Claude Clerselier included Cordemoy's essay ''Discours de l’áction des corps (A Discourse on the Action of Bodies)'', along with a discourse by Rohault, in the posthumous publication of Descartes' ''Le Monde (The World)''. The essay became one of the six discourses in ''Le Discernement du corps et de l’âme en six discours pour servir à l’éclaircissement de la physique'' ''(The Distinction of the Body and the Soul in Six Discourses, in Order to be Useful for the Clarification of Physics)'' (1666), one of Cordemoy’s two major works. In this work, which was strongly criticized at the time by the followers of Descartes, Cordemoy pointed out how often the two elements of mind and body in any human being fail to correspond with each other. ''Le Discernement du corps et de l’âme'' also elaborated Cordemoy’s arguments for occasionalism, and his atomism. Cordemoy introduced [[atomism]] into the mechanistic system of René Descartes by reconciling unity with the existence of substantial individual bodies; matter was homogeneous, but consisted of a multiplicity of bodies, each of which was an individual substance. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | In ''Copie d'une lettre ecrite à un sçavant religieux de la Compagnie de Jésus (A Copy of a Letter Written to a Learned Religious of the Company of Jesus)'', Cordemoy attempted to reconcile Cartesian philosophy with the story of creation in the ''Book of Genesis''. His shorter works include ''Traitez de Metaphysique (Treatise on Metaphysics)'' and ''Traitez sur l'Histoire et la Politique (Treatise on History and Politics)''. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Occasionalism=== | |

| − | + | Cordemoy was first known for having rethought the [[Descartes|Cartesian]] theory of causality, introducing the notion of “occasional cause” within an essentially Cartesian system of thought. Along with Arnold Geulincx and Louis de Laforge, he was a founder of the doctrine called “[[occasionalism]].” Body and soul were essentially and causally distinct; their combination was occasional, and it was God, for example, who allowed a person’s will to move his arm to be translated into a movement. It was also God who caused a person’s mind to experience sensations on the occasion of appropriate states of his physical body. The person’s will was an occasional cause of the movement of his arm, but God was the real cause of it. What was true for the individual human body, constituted by the distinct combination of body and soul, was true for every “body” in the universe. God was the real and universal cause of every movement. By “body,” Cordemoy meant the ultimate components of matter. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | Cordemoy used a judicial figure of speech to show that the “body,” in law a person, in physics an ultimate component of matter, was indivisible. Though he never mentioned atomism, his theory closely resembled the ideas of the followers of [[Gassendi]] and of the free thinkers—the so called [[Libertine]]s. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | ===Theory of speech=== | |

| + | Cordemoy's other important work, an examination of the nature of speech, ''Le Traité physique de la parole'' ''(A Physical Treatise on Speech)'', appeared in 1668. He elaborated on a problem which had been considered at the end of the sixth speech of ''The Distinction of the Body and the Soul:'' how can one, as a thinking being, be certain that the human beings who surround him are also thinking beings, and not simple automatons? Words, as vehicles of thought, enable people to know the existence of other individuals who are also endowed with souls. | ||

| − | + | In an original way, “''Le Traité physique de la parole''” ''(Physical Treatise on the Word)'', developed the notion that between the material (physical) sign and the expressed idea, there exists no motivated relationship, in the same way as no real relationship exists between body and soul. A word represents an opportunity for sign and meaning to meet. If the soul did not have the use of an articulated body to produce a sign, it would communicate in a much more immediate way with other souls, without going through the institution of the sign. | |

| − | + | The language used by human beings is too complex to be explained by purely mechanical causes; from language it can be deduced that other human bodies are also endowed with souls. Animals may utter sounds and parrots may reproduce words, but only human beings are able to communicate ideas, and that demonstrates the presence of a rational soul. (Although, technically, higher level primates are also capable of such communication.) This rational soul is able to communicate directly with angels without going through the physical articulation of the sign. ''Le Traité physique de la parole,'' from which [[Molière]] drew the scene of the spelling lesson in ''Le Bourgeois gentilhomme,'' remains the most successful work of Cordemoy. During the 1960s, his theories were revisited by American linguists such as [[Franz Boas|Boas]] and [[Noam Chomsky|Chomsky]]. | |

| + | |||

| + | ===Historian=== | ||

| + | Cordemoy is also known for his ''Histoire de France,'' on which he worked for 18 years without completing the job of researching and resolving the contradictions among the works of his predecessors. He was working on it at the time of his death; and the work was finished by his elder son, Louis-Géraud de Cordemoy, and published posthumously in two volumes, in 1685 and 1689. | ||

| − | + | [[Voltaire]] said about Cordemoy’s historical work, “He has been the first one to be able to disentangle the chaos of the two first races of the kings of France; thanks to the duke of Montausier who charged Cordemoy with the writing of the history of [[Charlemagne]] in view of the education of Monseigneur, that useful work was achieved. He found in ancient authors nothing but absurdities and contradictions. That very difficulty encouraged him, and enabled him to disentangle the two first races.” | |

| − | + | ==Publications== | |

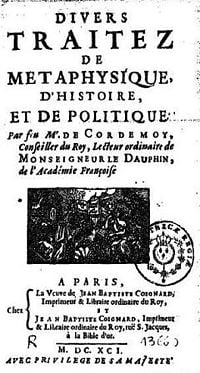

| − | + | [[Image:pagegardeopuscules.jpg|thumb|200px|right|'''1691 edition of the political and historical works of Géraud de Cordemoy''']] | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | *''Discours de l’action des corps'' (1664) | ||

| + | *''Traité de l'esprit de l'homme et de ses facultez et fonctions, et de son union avec le corps. Suivant les principes de René Descartes'' (1666) | ||

| + | *''Le discernement du corps et de l'âme, en six discours, pour servir à l'éclaircissement de la physique'' (1666) | ||

| + | *''Discours physique de la parole'' (1668). | ||

| + | *''Copie d'une lettre écrite à un sçavant religieux de la Compagnie de Jésus, pour montrer : I, que le système de M. Descartes et son opinion touchant les bestes n'ont rien de dangereux; II, et que tout ce qu'il en a écrit semble estre tiré du premier chapitre de la Genèse'' (1668) | ||

| + | *''Lettre d'un philosophe à un cartesien de ses amis'' (1672) | ||

| + | *''Discours sur la pureté de l'esprit et du corps et par occasion de la vie innocente et juste des premiers Chrétiens'' (1677) | ||

| + | *''Histoire de France, depuis le temps des Gaulois et le commencement de la monarchie, jusqu'en 987'' (2 volumes, 1687-1689) | ||

| + | *''Dissertations physiques sur le discernement du corps et de l'âme, sur la parole, et sur le système de M. Descartes'' (1689-1690) | ||

| + | *''Divers traitez de métaphysique, d'histoire et de politique'' (1691) | ||

| + | *''Les Œuvres de feu monsieur de Cordemoy'' (1704) | ||

| + | *''Gérauld de Cordemoy'' (1626-1684). Œuvres philosophiques. Avec une étude bio-bibliographique, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1968 | ||

| + | ==References== | ||

| + | *Ablondi, Fred. ''Gerauld de Cordemoy: Atomist, Occasionalist, Cartesian''. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2005. ISBN 1423733509 | ||

| + | *Balz, Albert G. A. ''Cartesian Studies''. New York: Columbia University Press, 1951. | ||

| + | *Balz, Albert G. A. ''Geraud de Cordemoy, 1600-1684''. Lancaster, Pa.: Lancaster Press, Inc., 1931. | ||

| + | *Battail, Jean-François. ''L’Avocat philosophe Géraud de Cordemoy (1626-1684)''. La Haye: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973. | ||

| + | *Boas, George. ''Cordemoy and Malebranche: Dominant Themes of Modern Philosophy, a History''. New York: Ronald Press Co., 1957. | ||

| + | *Chomsky, Noam. ''Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought''. New York: Harper & Row, 1966. | ||

| + | *Deprun, Jean. ''Cordemoy et la réforme de l’enseignement''. Marseille, 1972. | ||

| + | *Descartes, René, Daniel Garber, and Roger Ariew. ''Descartes in Seventeenth Century England''. Bristol: Thoemmes, 2002. ISBN 1855069903 | ||

| + | *Guerrini, Luigi. "Occasinalismo e teoria della communicazione in Gerauld de Cordemoy" in ''Annali di dipartimento di filosofia'', IX, 1993 (1994), 63–80. | ||

| + | *Nadler, Steven. "Cordemoy and Occasionalism" ''Journal of the History of Philosophy'' 43: 37-54, 2005. | ||

| + | *Scheib, Andreas. ''Zur Theorie individueller Substanzen bei Géraud de Cordemoy'' Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1997. ISBN 363130594X | ||

==External links== | ==External links== | ||

| + | All links retrieved July 22, 2017. | ||

| + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/entries/cordemoy/ Geraud de Cordemony] – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. | ||

| + | *[http://phclavier.chez-alice.fr/ (fr) Website devoted to Géraud de Cordemoy]. | ||

| − | + | ===General philosophy sources=== | |

| − | + | *[http://plato.stanford.edu/ Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.iep.utm.edu/ The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy]. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.bu.edu/wcp/PaidArch.html Paideia Project Online]. | |

| − | + | *[http://www.gutenberg.org/ Project Gutenberg]. | |

| − | + | ||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| + | [[Category:philosophers]] | ||

{{credit|125320820}} | {{credit|125320820}} | ||

Latest revision as of 23:03, 22 July 2017

Géraud de Cordemoy, (October 6, 1626 - October 15, 1684) was a French philosopher, historian, and lawyer, known for his works in metaphysics and for his theory of language. Though a lawyer by profession, Cordemoy was a prominent figure in Parisian philosophical circles. He was one of the early Cartesian philosophers, active during the decades immediately following the death of Descartes.

His major works include Le Discernement du corps et de l'âme (The Differentiation of the Body and the Soul, 1666), in which he incorporated atomism into a Cartesian mechanistic system, and pointed out that the two elements of mind and body in any human being often fail to correspond with each other. Along with Arnold Geulincx and Louis de Laforge, he developed occasionalism, the doctrine that body and soul were essentially and causally distinct and that it was only God who allowed a person’s will to move his physical body, or a person’s mind to experience sensations originating from the physical body. The same was true for every “body,” or entity, in the universe; therefore, God was the real and universal cause of every movement. Le Traité physique de la parole (A Physical Treatise on Speech, 1668) suggested that human’s ability to use words as vehicles of thought demonstrated the existence of a rational soul.

Cordemoy accepted the ontological framework of Descartes, who identified body with extension and mind with thought. His acceptance of Descartes' framework limited philosophical paths he could take. While his occasionalism left a perspective in the history of modern philosophy, later thinkers questioned validity of Descartes' presuppositions themselves.

Life

Géraud de Cordemoy was born October 6, 1626, to a family of ancient nobility originating from Auvergne (from the town of Royat) in France. He was the only son, and the third of four children, of Géraud and Nicole de Cordemoy. His father was a master in arts at the University of Paris, and died when Géraud was nine years old. Little is known about his early years or his education. He married Marie de Chazelles, and the birth of the first of his five children is recorded on December 7, 1651.

Géraud was a private tutor and linguist and practiced as a lawyer. He associated with the philosophical circles of Paris, attending various salons, and made the acquaintance of Emmanuel Maignan and the physicist Jacques Rohault. He was a friend and a protégé of Jacques-Benigne Bossuet, a French bishop and orator who also admired Descartes. Géraud de Cordemoy was appointed tutor for the Dauphin, son of King Louis XIV, at the same time as Fléchier, and was elected a member of the Académie Française in 1675, where he served briefly as director. He died, after a brief illness, on October 15, 1684.

Thought and works

Géraud de Cordemoy was one of the early and more important Cartesian philosophers, active during the decades immediately following the death of Descartes.

In 1664, Claude Clerselier included Cordemoy's essay Discours de l’áction des corps (A Discourse on the Action of Bodies), along with a discourse by Rohault, in the posthumous publication of Descartes' Le Monde (The World). The essay became one of the six discourses in Le Discernement du corps et de l’âme en six discours pour servir à l’éclaircissement de la physique (The Distinction of the Body and the Soul in Six Discourses, in Order to be Useful for the Clarification of Physics) (1666), one of Cordemoy’s two major works. In this work, which was strongly criticized at the time by the followers of Descartes, Cordemoy pointed out how often the two elements of mind and body in any human being fail to correspond with each other. Le Discernement du corps et de l’âme also elaborated Cordemoy’s arguments for occasionalism, and his atomism. Cordemoy introduced atomism into the mechanistic system of René Descartes by reconciling unity with the existence of substantial individual bodies; matter was homogeneous, but consisted of a multiplicity of bodies, each of which was an individual substance.

In Copie d'une lettre ecrite à un sçavant religieux de la Compagnie de Jésus (A Copy of a Letter Written to a Learned Religious of the Company of Jesus), Cordemoy attempted to reconcile Cartesian philosophy with the story of creation in the Book of Genesis. His shorter works include Traitez de Metaphysique (Treatise on Metaphysics) and Traitez sur l'Histoire et la Politique (Treatise on History and Politics).

Occasionalism

Cordemoy was first known for having rethought the Cartesian theory of causality, introducing the notion of “occasional cause” within an essentially Cartesian system of thought. Along with Arnold Geulincx and Louis de Laforge, he was a founder of the doctrine called “occasionalism.” Body and soul were essentially and causally distinct; their combination was occasional, and it was God, for example, who allowed a person’s will to move his arm to be translated into a movement. It was also God who caused a person’s mind to experience sensations on the occasion of appropriate states of his physical body. The person’s will was an occasional cause of the movement of his arm, but God was the real cause of it. What was true for the individual human body, constituted by the distinct combination of body and soul, was true for every “body” in the universe. God was the real and universal cause of every movement. By “body,” Cordemoy meant the ultimate components of matter.

Cordemoy used a judicial figure of speech to show that the “body,” in law a person, in physics an ultimate component of matter, was indivisible. Though he never mentioned atomism, his theory closely resembled the ideas of the followers of Gassendi and of the free thinkers—the so called Libertines.

Theory of speech

Cordemoy's other important work, an examination of the nature of speech, Le Traité physique de la parole (A Physical Treatise on Speech), appeared in 1668. He elaborated on a problem which had been considered at the end of the sixth speech of The Distinction of the Body and the Soul: how can one, as a thinking being, be certain that the human beings who surround him are also thinking beings, and not simple automatons? Words, as vehicles of thought, enable people to know the existence of other individuals who are also endowed with souls.

In an original way, “Le Traité physique de la parole” (Physical Treatise on the Word), developed the notion that between the material (physical) sign and the expressed idea, there exists no motivated relationship, in the same way as no real relationship exists between body and soul. A word represents an opportunity for sign and meaning to meet. If the soul did not have the use of an articulated body to produce a sign, it would communicate in a much more immediate way with other souls, without going through the institution of the sign.

The language used by human beings is too complex to be explained by purely mechanical causes; from language it can be deduced that other human bodies are also endowed with souls. Animals may utter sounds and parrots may reproduce words, but only human beings are able to communicate ideas, and that demonstrates the presence of a rational soul. (Although, technically, higher level primates are also capable of such communication.) This rational soul is able to communicate directly with angels without going through the physical articulation of the sign. Le Traité physique de la parole, from which Molière drew the scene of the spelling lesson in Le Bourgeois gentilhomme, remains the most successful work of Cordemoy. During the 1960s, his theories were revisited by American linguists such as Boas and Chomsky.

Historian

Cordemoy is also known for his Histoire de France, on which he worked for 18 years without completing the job of researching and resolving the contradictions among the works of his predecessors. He was working on it at the time of his death; and the work was finished by his elder son, Louis-Géraud de Cordemoy, and published posthumously in two volumes, in 1685 and 1689.

Voltaire said about Cordemoy’s historical work, “He has been the first one to be able to disentangle the chaos of the two first races of the kings of France; thanks to the duke of Montausier who charged Cordemoy with the writing of the history of Charlemagne in view of the education of Monseigneur, that useful work was achieved. He found in ancient authors nothing but absurdities and contradictions. That very difficulty encouraged him, and enabled him to disentangle the two first races.”

Publications

- Discours de l’action des corps (1664)

- Traité de l'esprit de l'homme et de ses facultez et fonctions, et de son union avec le corps. Suivant les principes de René Descartes (1666)

- Le discernement du corps et de l'âme, en six discours, pour servir à l'éclaircissement de la physique (1666)

- Discours physique de la parole (1668).

- Copie d'une lettre écrite à un sçavant religieux de la Compagnie de Jésus, pour montrer : I, que le système de M. Descartes et son opinion touchant les bestes n'ont rien de dangereux; II, et que tout ce qu'il en a écrit semble estre tiré du premier chapitre de la Genèse (1668)

- Lettre d'un philosophe à un cartesien de ses amis (1672)

- Discours sur la pureté de l'esprit et du corps et par occasion de la vie innocente et juste des premiers Chrétiens (1677)

- Histoire de France, depuis le temps des Gaulois et le commencement de la monarchie, jusqu'en 987 (2 volumes, 1687-1689)

- Dissertations physiques sur le discernement du corps et de l'âme, sur la parole, et sur le système de M. Descartes (1689-1690)

- Divers traitez de métaphysique, d'histoire et de politique (1691)

- Les Œuvres de feu monsieur de Cordemoy (1704)

- Gérauld de Cordemoy (1626-1684). Œuvres philosophiques. Avec une étude bio-bibliographique, Presses Universitaires de France, Paris, 1968

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ablondi, Fred. Gerauld de Cordemoy: Atomist, Occasionalist, Cartesian. Milwaukee: Marquette University Press, 2005. ISBN 1423733509

- Balz, Albert G. A. Cartesian Studies. New York: Columbia University Press, 1951.

- Balz, Albert G. A. Geraud de Cordemoy, 1600-1684. Lancaster, Pa.: Lancaster Press, Inc., 1931.

- Battail, Jean-François. L’Avocat philosophe Géraud de Cordemoy (1626-1684). La Haye: Martinus Nijhoff, 1973.

- Boas, George. Cordemoy and Malebranche: Dominant Themes of Modern Philosophy, a History. New York: Ronald Press Co., 1957.

- Chomsky, Noam. Cartesian Linguistics: A Chapter in the History of Rationalist Thought. New York: Harper & Row, 1966.

- Deprun, Jean. Cordemoy et la réforme de l’enseignement. Marseille, 1972.

- Descartes, René, Daniel Garber, and Roger Ariew. Descartes in Seventeenth Century England. Bristol: Thoemmes, 2002. ISBN 1855069903

- Guerrini, Luigi. "Occasinalismo e teoria della communicazione in Gerauld de Cordemoy" in Annali di dipartimento di filosofia, IX, 1993 (1994), 63–80.

- Nadler, Steven. "Cordemoy and Occasionalism" Journal of the History of Philosophy 43: 37-54, 2005.

- Scheib, Andreas. Zur Theorie individueller Substanzen bei Géraud de Cordemoy Frankfurt am Main: P. Lang, 1997. ISBN 363130594X

External links

All links retrieved July 22, 2017.

- Geraud de Cordemony – Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- (fr) Website devoted to Géraud de Cordemoy.

General philosophy sources

- Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy.

- Paideia Project Online.

- Project Gutenberg.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.