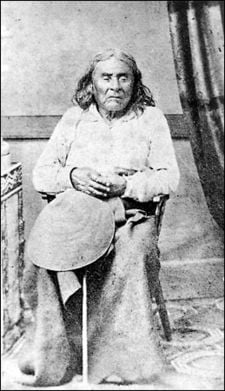

Chief Seattle

Chief Seattle or Sealth (Lushootseed: siʔaɬ; c. 1786 – June 7, 1866), also spelled Seathle, Seathl, or See-ahth, was a leader of the Suquamish and Duwamish Native American tribes in what is now the U.S. state of Washington. A prominent figure among his people, he pursued a path of accommodation to white settlers, forming a personal relationship with David Swinson "Doc" Maynard. Seattle, Washington was named after him.

Biography

Childhood

Chief Seattle was born around 1786 on or near Blake Island, Washington. His father, Schweabe, was a leader of the Suquamish tribe of Agate Pass, between Bainbridge Island and the mainland of Washington state's Kitsap Peninsula across Puget Sound from the present city of Seattle. Seattle's mother was Sholitza (sometimes Wood-sho-lit-sa), the daughter of a Duwamish chief, from near the lower Green River area. As the line of descent traditionally ran through the mother, Seattle was considered Duwamish. Both the Suquamish and Duwamish are Coast Salish peoples. Seattle's given name at birth was Sealth.

The exact year of Sealth's birth is not known, but he was believed to have been about 80 years old when he died on June 6, 1866. Sealth had reached his middle years before he appeared in the historic record, therefore information about his early years is fragmentary.

Sealth reported that he was present when the British ship H.M.S. Discovery, captained by George Vancouver, anchored off Bainbridge Island on May 20, 1792. Chief Kitsap, war chief of the Suquamish and uncle of Sealth, was one of the most powerful chiefs on Puget Sound from 1790 to 1845. It its believed that Kitsap was one of the Indians who was welcomed aboard the Discovery, bringing his nephew with him. It is said that the visit so impressed the young boy that it had a positive effect on his future dealings with white settlers.

Adulthood

Sealth took wives from the village of Tola'ltu just southeast of Duwamish Head on Elliott Bay (now part of West Seattle). His first, wife La-Dalia, died after bearing a daughter. He had three sons and four daughters with his second wife, Olahl[1]. The most famous of his children was his first, Kikisoblu or Princess Angeline.

Around 1825, The Puget Sound Indians, not normally organized above the level of individual bands, formed a confederation under Kitsap to strike against the alliance of Cowichan-area tribes of southeast Vancouver Island, who often raided the Puget Sound. However, Kitsap's flotilla was no match for the larger canoes of the Cowichans; after suffering heavy losses in the sea battle, the Puget Sound Indians were forced to retreat. Kitsap was one of the few survivors of the ill-fated expedition. At the same time, Sealth succeeded in ambushing and destroying a party of raiders coming down the Green River in canoes from their strongholds in the Cascade foothills. His reputation grew stronger as he continued; attacking the Chemakum and the S'Klallam tribes living on the Olympic Peninsula, and participating in raids on the upper Snoqualmie River. Sealth eventually gained control of six local tribes.

White settlement

By 1833, when the Hudson's Bay Company founded Fort Nisqually near the head of Puget Sound, Sealth had a solid reputation as an intelligent and formidable leader with a compelling voice.[2] He was also known as an orator, and when he addressed an audience, his voice is said to have carried from his camp to the Stevens Hotel at First and Marion, a distance of three-quarters of a mile. He was tall and broad for a Puget Sound native at nearly six feet; Hudson's Bay Company traders gave him the nickname Le Gros (The Big One). [1].

In 1847 Sealth helped lead the Suquamish in an attack upon the Chemakum stronghold of Tsetsibus, near Port Townsend, that effectively wiped out this rival group. The death of one of his sons during the raid affected him deeply, for not long after that he was baptized into the Roman Catholic Church, and given the baptismal name Noah. He is believed to have received his baptism by the Oblates of Mary Immaculate at their St. Joseph of Newmarket Mission, founded near the new settlement of Olympia in 1848. Sealth also had his children baptized and raised as Catholics.[2].

This conversion was a turning point for Sealth and the Duwamish, as it marked the end of his fighting days and his emergence as leader known as a "friend to the whites."

White settlers began arriving in the Puget Sound area in 1846, and in the area that later became the city of Seattle, in 1851. Sealth welcomed the settlers and sought out friendships with those with whom he could do business. His initial contact was with a San Francisco merchant, Charles Fay, with whom he organized a fishery on Elliott Bay in the summer of 1851.[2]. When Fay returned to San Francisco, Chief Sealth moved south to Olympia. Here he took up with David S. "Doc" Maynard. Sealth helped protect the small band of settlers in what is now Seattle from attacks by other Indians. Because of his friendship and assistance, it was Maynard who advocated for naming the settlement "Seattle" after Chief Sealth. When the first plats for the village were filed on May 23, 1853, it was for the "Town of Seattle".

Seattle was unique in its settlement in that a strong Native chief befriended the early settlers and sought to form a blended community of red and white peoples. While many influential whites attempted to keep their people separate from the native population, Sealth's friendship remained steadfast.

Sealth served as native spokesman during the treaty council held at Point Elliott (later Mukilteo), from December 27, 1854, to January 9, 1855. While he voiced misgivings about ceding title to some 2.5 million acres of land, he understood the futility of opposing a force so much larger than his own people. In signing the treaty and retaining a reservation for the Suquamish but not for the Duwamish, he lost the support of the latter. This unhappiness soon led to the Yakima Indian War of 1855-1857.

Sealth kept his people out of the Battle of Seattle (1856). Afterwords he unsuccessfully sought clemency for the war leader, Leschi. On the reservation, he attempted to curtail the influence of whiskey sellers and he interceded between the whites and the natives. Off the reservation, he participated in meetings to resolve native disputes.

Sealth maintained his friendship with Maynard and cultivated new relationships with other settlers. He was unwilling to lead his tribe to the reservation established, since mixing Duwamish and Snohomish was likely to lead to bloodshed. Maynard persuaded the government of the necessity of allowing Sealth to remove to his father's longhouse on Agate Passage, 'Old Man House' or Tsu-suc-cub. Sealth frequented the town named after him, and had his photograph taken by E. M. Sammis in 1865.[1] He died June 7, 1866, on the Suquamish reservation at Port Madison, Washington.

Legacy

- Sealth's grave site is at the Suquamish Tribal Cemetery.[3]

- In 1890, a group of Seattle pioneers led by Arthur Armstrong Denny set up a monument over his grave, with the inscription "SEATTLE Chief of the Suqamps and Allied Tribes, Died June 7, 1866. The Firm Friend of the Whites, and for Him the City of Seattle was Named by Its Founders" On the reverse is the inscription "Baptismal name, Noah Sealth, Age probably 80 years."[1] The site was restored and a native sculpture added in 1976.

- The Suquamish Tribe honors Chief Seattle every third week in August at "Chief Seattle Days."

- The city of Seattle, and numerous related features, are named after Sealth.

The Speech Controversy

There is a controversy about a speech by Sealth concerning the concession of native lands to the settlers.

Even the date and location of the speech has been disputed,[4] but the most common version is that on March 11, 1854, Sealth gave a speech at a large outdoor gathering in Seattle. The meeting had been called by Governor Isaac Ingalls Stevens to discuss the surrender or sale of native land to white settlers. Doc Maynard introduced Stevens, who then briefly explained his mission, which was already well understood by all present.[1]

Sealth then rose to speak. He rested his hand upon the head of the much smaller Stevens, and declaimed with great dignity for an extended period. No one alive today knows what he said; he spoke in the Lushootseed language, and someone translated his words into Chinook Indian trade language, and a third person translated that into English.

Some years later, Dr. Henry A. Smith wrote down an English version of the speech, based on Smith's notes. It was a flowery text in which Sealth purportedly thanked the white people for their generosity, demanded that any treaty guarantee access to Native burial grounds, and made a contrast between the God of the white people and that of his own. Smith noted that he had recorded "...but a fragment of his [Sealth's] speech". Recent scholarship questions the authenticity of Smith's supposed translation.[5]

In 1891, Frederick James Grant's History of Seattle, Washington reprinted Smith's version. In 1929, Clarence B. Bagley's History of King County, Washington reprinted Grant's version with some additions. In 1931, John M. Rich reprinted the Bagley version in Chief Seattle's Unanswered Challenge. In the 1960s, articles by William Arrowsmith and the growth of environmentalism revived interest in Sealth's speech. Ted Perry introduced anachronistic material, such as shooting buffalo from trains, into a new version for a movie called "Home"[6], produced for the Southern Baptist Convention's Christian Radio and Television Commission.[7] The movie sunk without a trace, but this newest and most fictional version is the most widely known. Albert Furtwangler analyzes the evolution of Sealth's speech in Answering Chief Seattle (1997).[8]

The speech attributed to Sealth, as re-written by others, has been widely cited as "powerful, bittersweet plea for respect of Native American rights and environmental values"[6], but there is little evidence that he actually spoke it. A similar controversy surrounds a purported 1855 letter from Sealth to President Franklin Pierce, which has never been located and, based on internal evidence, is considered by some historians as "an unhistorical artifact of someone's fertile literary imagination".[4]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Emily Inez Denny. 1909, reprinted 1984. Blazing the Way. Seattle Historical Society.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Buerge

- ↑ Suquamish Culture. Suquamish Tribe. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Jerry L. Clark (Spring, 1985). Thus Spoke Chief Seattle: The Story of An Undocumented Speech. The National Archives. Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ BOLA Architecture + Planning & Northwest Archaeological Associates, Inc., Port of Seattle North Bay Project DEIS: Historic and Cultural Resources, Port of Seattle, April 5, 2005. Accessed online 25 July 2008. p.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Chief Seattle's Speech. HistoryLink (2001). Retrieved July 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Territorial Governor Isaac Stevens & Chief Seattle," Museum of History and Industry, Seattle, Wash., June, 1990; reprinted on The eJournal Website

- ↑ Furtwangler, Albert (1997). Answering Chief Seattle. University of Washington Press. Retrieved August 31, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Buerge, David M. Chief Seattle and Chief Joseph: From Indians to Icons University of Washington Libraries. Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Chief Seattle Arts. Noah Seattle Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Furtwangler, Albert, and Seattle. 1997. Answering Chief Seattle. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 9780295976334 Online version Retrieved December 17, 2008.

- Morgan, Murray. 1982. Skid road: an informal portrait of Seattle. Seattle: University of Washington Press. ISBN 0295958464 and ISBN 9780295958460

- Speidel, William C. 1978. Doc Maynard: the man who invented Seattle. Seattle: Nettle Creek Pub. Co. ISBN 0914890026 and ISBN 9780914890027

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.