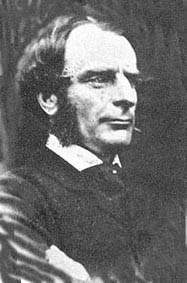

Charles Kingsley

Charles Kingsley (June 12 1819 – January 23 1875) was an English novelist, particularly associated with the West Country and north-east Hampshire.

Life & Character

Kingsley was born in Holne Vicarage, near Devonshire. His father, Rev. Charles Kingsley, was from a line of country gentlemen, but he turned to priesthood to support himself financially. His mother, Mary, was born in the West Indies of sugar-plantation owners. His brother, Henry Kingsley, also became a novelist.

Kingsley spent his childhood in Clovelly and was educated at Bristol Grammar School. It was here in Bristol that he witnessed the 1831 Reform Bill riots, which he later counted as a defining moment in his social thought. As a young student, Kingsley was enthusiastic about art and natural sciences, and often wrote poetry. When his father was appointed rector at Saint Luke's, Chelsea, the family moved to London and the young Kingsley enrolled at King's College, where he met future wife Frances ‘Fanny’ Grenfell—they married in 1844. In 1842, Charles left for Cambridge to read for Holy Orders at Magdalene College. He was originally intended for the legal profession, but changed his mind and chose to pursue a ministry in the church.

With F.D. Maurice as his mentor, Kingsley believed that true religion must incorporate the social and political spheres of life, and thus, he worked tirelessly toward the educational, physical, and social betterment of his congregation. In 1844, he was appointed rector of Eversley in Hampshire. In November the same year, his first child, Rose, was born. His son Maurice followed in 1847, and daughter Mary St. Leger, who later authored novels under the pen name Lucas Malet, was born in 1852.

In 1860, he was appointed Regius Professor of Modern History at the University of Cambridge.

In 1872 Kingsley accepted the Presidency of the Birmingham and Midland Institute and became its 19th President.[1]

Kingsley died in 1875 and was buried in St Mary's Churchyard in Eversley.

In person Charles Kingsley was tall and spare, sinewy rather than powerful, and of a restless excitable temperament. His complexion was swarthy, his hair dark, and his eye bright and piercing. His temper was hot, kept under rigid control; his disposition tender, gentle and loving, with flashing scorn and indignation against all that was ignoble and impure; he was a good husband, father and friend.

Kingsley's life was written by his widow in 1877, entitled Charles Kingsley, his Letters and Memories of his Life, and presents a very touching and beautiful picture of her husband, but perhaps hardly does justice to his humor, his wit, his overflowing vitality and boyish fun.

Influences & Works

Counting F.D. Maurice as a principal influence in his life, Kingsley committed himself to the Christian Socialist movement, alongside John Malcolm Ludlow and Thomas Hughes. His literary career would thoroughly display the social causes that he suppported.

One such work was Yeast: A Problem, featured first in Fraser's Magazine in 1848, before being published in book form in 1851. It underlined the plight experienced by agricultural laborers in England. His works Cheap Clothes and Nasty and "Alton Locke, Tailor and Poet shed light on the working conditions of the sweated tailors' trade.

In 1849, Kingsley and his counterparts worked tirelessly to spread awareness of and aid to sufferers of the cholera epidemic sweeping London's East End. This paved the way to a lifelong dedication to teaching proper hygiene and sanitation to the masses, both publicly and in his novels. In 1854 he spoke before the House of Commons to promote public health reform. The subject of sanitary habits was also a main component of his children's novel The Water Babies.

In addition to his commitment to social causes, Kingsley also was deeply invested in writing historical fiction, as shown in The Heroes (1856), a children's book about Greek mythology, and several historical novels, of which the best known are Hypatia (1853), Hereward the Wake (1865), and Westward Ho! (1855). His first major work under the genre, Hypatia, was issued in two volumes in 1853. Set just before the fall of Alexandria, Hypatia told the story of the various schools of thought in conflict, most notably the crisis between Christianity and Neo-Platonism.

With his most popular historical novel, Westward Ho!, Kingsley romantically depicted the divisions occurring within Christianity itself, between Protestant England and Catholic Spain. In this critically-praised adventure story, Kingsley's protagonist hero, Amyas Leigh, aids the English army in defeating the Spanish Armada. With Amyas, Kingsley created his representation of an ideal Elizabethan-age Victorian boy. Though the book was noted for its realistic descriptions, perhaps its fault was with its ethnic bias. Along with his Victorian themes, Kingsley also projected Victorian attitudes about race. Indeed, he once wrote to his wife, describing a visit to Ireland, "I am haunted by the human chimpanzees I saw along that hundred miles of horrible country. I don't believe they are our fault. I believe there are not only many of them than of old, but they are happier, better, more comfortably fed and lodged under our rule than they ever were. But to see white chimpanzees is dreadful; if they were black, one would not feel it so much, but their skins, except where tanned by exposure, are as white as ours." [2]

The public detected a possible shift in Kingsley's political attitudes, with the publication of Two Years Ago (1857), a novel for adults, replete with the themes of sanitation reform, the abolition of slavery, and the importance of scientific study. It seemed that by focusing less on the plight of laborers, Kingsley was positioning himself further from the Christian Socialist cause that he once represented. In turn, the novel caused him to be associated with the cult of "muscular Christianity."

His most pressing scientific and educational views and his concern for social reform are illustrated in his most famous work, the children's classic The Water-Babies (1863), a kind of fairytale about Tom, a poor boy chimney-sweep. Originally intended as a short story written for Kingsley's youngest child, the novel chronicles the rebirth of Tom as a water-baby, and his subsequent adventures alongside many different creatures. It has been noted that in The Water-Babies, Kingsley wrote of something of a purgatory, which ran counter to his "Anti-Roman" theology. The story also mentions the main protagonists in the scientific debate over Charles Darwin's On the Origin of Species, gently satirizing their reactions.

Holding the belief that nature was imbued with a cathartic spirit, he was sympathetic to the idea of evolution, and was one of the first to praise Darwin's book. He had been sent an advance review copy and in his response of 18 November 1859 (four days before the book went on sale) stated that he had "long since, from watching the crossing of domesticated animals and plants, learnt to disbelieve the dogma of the permanence of species."[3]. Darwin added an edited version of Kingsley's closing remarks to the next edition of his book, stating that "A celebrated author and divine has written to me that 'he has gradually learnt to see that it is just as noble a conception of the Deity to believe that He created a few original forms capable of self-development into other and needful forms, as to believe that He required a fresh act of creation to supply the voids caused by the action of His laws'." [4]

During his remaining years, Kingsley continued to write poetry and political articles, as well as several volumes of sermons. His famous ongoing dispute with the Venerable John Henry Newman, was made public made public when Kingsley ran a letter in Macmillan's Magazine, accusing Newman and the Catholic Church of untruthfulness and deceit, prompting a subsequent public battle in print. Newman defeated Kingsley with poise and intellect, exhibited in his Apologia Pro Vita Sua, which clearly showed the strength of Kingsley's invective and the distress it induced.

Legacy

As a novelist his chief power lay in his descriptive faculties. The descriptions of South American scenery in Westward Ho!, of the Egyptian desert in Hypatia, of the North Devon scenery in Two Years Ago, are brilliant; and the American scenery is even more vividly and more truthfully described when he had seen it only by the eye of his imagination than in his work At Last, which was written after he had visited the tropics. His sympathy with children taught him how to secure their interests. His version of the old Greek stories entitled The Heroes, and Water-babies and Madam How and Lady Why, in which he deals with popular natural history, take high rank among books for children.

Charles Kingsley's novel Westward Ho! led to the founding of a town by the same name and even inspired the construction of a railway, the Bideford, Westward Ho! and Appledore Railway. Few authors can have had such a significant effect upon the area which they eulogized. A hotel in Westward Ho! was named for him and it was also opened by him.

A hotel opened in 1897 in Bloomsbury, London, was named after Kingsley. It still exists, but changed name in 2001 to the Thistle Bloomsbury. The original reasons for the chosen name was that the hotel was opened by tee-totallers who admired Kingsley for his political and ideas on social reform.

Bibliography

- Saint's Tragedy, a drama (1848)

- Alton Locke, a novel (1849)

- Yeast, a novel (1849)

- Twenty-five Village Sermons (1849)

- Phaeton, or Loose Thoughts for Loose Thinkers (1852)

- Sermons on National Subjects (1st series, 1852)

- Hypatia, a novel (1853)

- Glaucus, or the Wonders of the Shore (1855)

- Sermons on National Subjects (2nd series, 1854)

- Alexandria and her Schools (I854)

- Westward Ho!, a novel (1855)

- Sermons for the Times (1855)

- The Heroes, Greek fairy tales (1856)

- Two Years Ago, a novel (1857)

- Andromeda and other Poems (1858)

- The Good News of God, sermons (1859)

- Miscellanies (1859)

- Limits of Exact Science applied to History (Inaugural Lectures, 1860)

- Town and Country Sermons (1861)

- Sermons on the Pentateuch (1863)

- The Water-Babies (1863)

- The Roman and the Teuton (1864)

- David and other Sermons (1866)

- Hereward the Wake, a novel (1866)

- The Ancient Régime (Lectures at the Royal Institution, 1867)

- Water of Life and other Sermons (1867)

- The Hermits (1869)

- Madam How and Lady Why (1869)

- At Last: A Christmas in the West Indies (1871)

- Town Geology (1872)

- Discipline and other Sermons (1872)

- Prose Idylls (1873)

- Plays and Puritans (1873)

- Health and Education (1874)

- Westminster Sermons (1874)

- Lectures delivered in America (1875)

Notes

- ↑ Presidents of the BMI, BMI, nd (c.2005). Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ L. P. Curtis, Jr, Anglo-Saxons and Celts (Bridgeport, Ct; 1968),p.84. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ Darwin 1887, p. 287.Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- ↑ Darwin 1860, p. 481.Retrieved September 21, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Darwin, Charles (1860), On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, London: John Murray 2nd edition. Retrieved on 2007-07-20

- Darwin, Charles (1887), The life and letters of Charles Darwin, including an autobiographical chapter., London: John Murray (The Autobiography of Charles Darwin) Retrieved on 2007-07-20

- Rapple, Brendan A. Dictionary of Literary Biography, "Volume 163: British Children's Writers, 1800-1880". A Bruccoli Clark Layman Book. Edited by Meena Khorana, Morgan State University. The Gale Group, 1996. pp. 136-147.

External links

- "Kingsley, Charles". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- "Charles Kingsley- Summary Bibliography". The Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved September 21, 2007.

- Uffelman, Larry K. "Charles Kingsley: A Biography". The Victorian Web. Retrieved September 26, 2007.

Template:19CBritChildrensLiterature This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.