Difference between revisions of "Camp meeting" - New World Encyclopedia

m (→History) |

|||

| Line 10: | Line 10: | ||

As tens of thousands of Americans began to move west in the late eighteenth century, the lack of churches in the new settlements created a [[religion|religious]] vacuum. Not only were there few authorized houses of [[worship]], there were even fewer [[ordination|ordained]] [[religious minister|ministers]] to fill even the pulpits of these small churches. The "camp meeting" was an innovative response to this situation. | As tens of thousands of Americans began to move west in the late eighteenth century, the lack of churches in the new settlements created a [[religion|religious]] vacuum. Not only were there few authorized houses of [[worship]], there were even fewer [[ordination|ordained]] [[religious minister|ministers]] to fill even the pulpits of these small churches. The "camp meeting" was an innovative response to this situation. | ||

| − | Word of mouth told that there was to be a religious meeting at a certain location. The promise of a skilled preacher and a large gathering of people created a highly attractive event. Due to the still primitive means of [[transportation]] of the time, meetings often involved families leaving home for several days, usually [[camping]] out near its site, as there were rarely adequate accommodations or the funds necessary to obtain them. The meetings thus represented a kind of vacation from the day-to-day routines of settlements and neighboring farms, as well as a chance to meet old friends, relations, new acquaintances, and even prospective marriage partners in a religiously-based atmosphere. | + | Word of mouth told that there was to be a religious meeting at a certain location. The promise of a skilled preacher and a large gathering of people created a highly attractive event. Due to the still primitive means of [[transportation]] of the time, meetings often involved families leaving home for several days, usually [[camping]] out near its site, as there were rarely adequate accommodations or the funds necessary to obtain them. The meetings thus represented a kind of vacation from the day-to-day routines of settlements and neighboring farms, as well as a chance to meet old friends, relations, new acquaintances, and even prospective marriage partners in a religiously-based atmosphere. While they were thus primarily religious in character, camp meetings were thus festive affairs, often held annually or to coincide with a time when farm life did not require daily attendance to crops, creating an almost vacation-like atmosphere. |

At a large camp meeting, thousands came from over a large area, some out of sincere religious devotion or interest, others out of curiosity and a desire for a break from the arduous [[frontier]] routine. Many in the latter group often became sincere converts as a result of the powerful preaching, singing, and testimonies generated at the meetings. The meetings provided participants with almost continuous services. Sermons of great power were the rule, in contrast to the staid ceremony of many established Eastern chruches, and speakers competed with each other in skill, enthusiasm, and ability to be heard by the large crowds. Once one speaker was finished, often after several hours, another would often rise to take his place. Singing would break the monotony of the sermons, and many simple but powerful hymns resulted. | At a large camp meeting, thousands came from over a large area, some out of sincere religious devotion or interest, others out of curiosity and a desire for a break from the arduous [[frontier]] routine. Many in the latter group often became sincere converts as a result of the powerful preaching, singing, and testimonies generated at the meetings. The meetings provided participants with almost continuous services. Sermons of great power were the rule, in contrast to the staid ceremony of many established Eastern chruches, and speakers competed with each other in skill, enthusiasm, and ability to be heard by the large crowds. Once one speaker was finished, often after several hours, another would often rise to take his place. Singing would break the monotony of the sermons, and many simple but powerful hymns resulted. | ||

Revision as of 03:49, 10 January 2009

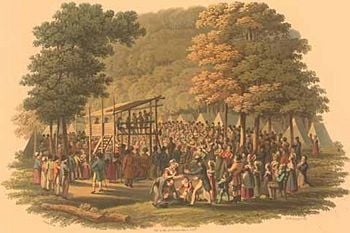

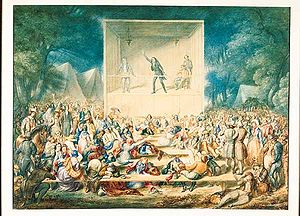

Camp meetings were outdoor religious gatherings that became a prominent feature of the nineteenth century American frontier. Held by various Protestant denominations to minister to the spiritual needs of western, largely un-churched, settlements, they developed into major cultural events as well as revivals.

The first known large camp meetings were led by Reverend the Presbyterian James McGready c. 1797-1800. By the turn of the nineteenth century, the camp meeting movement had spread throughout the American South and West. The movement formed part of the Great Awakening and contributed to the American style of worship and preaching. The English founders of Primitive Methodism took inspiration from the camp meets as a way of holding an extended prayer meeting.

Camp meetings in America

As tens of thousands of Americans began to move west in the late eighteenth century, the lack of churches in the new settlements created a religious vacuum. Not only were there few authorized houses of worship, there were even fewer ordained ministers to fill even the pulpits of these small churches. The "camp meeting" was an innovative response to this situation.

Word of mouth told that there was to be a religious meeting at a certain location. The promise of a skilled preacher and a large gathering of people created a highly attractive event. Due to the still primitive means of transportation of the time, meetings often involved families leaving home for several days, usually camping out near its site, as there were rarely adequate accommodations or the funds necessary to obtain them. The meetings thus represented a kind of vacation from the day-to-day routines of settlements and neighboring farms, as well as a chance to meet old friends, relations, new acquaintances, and even prospective marriage partners in a religiously-based atmosphere. While they were thus primarily religious in character, camp meetings were thus festive affairs, often held annually or to coincide with a time when farm life did not require daily attendance to crops, creating an almost vacation-like atmosphere.

At a large camp meeting, thousands came from over a large area, some out of sincere religious devotion or interest, others out of curiosity and a desire for a break from the arduous frontier routine. Many in the latter group often became sincere converts as a result of the powerful preaching, singing, and testimonies generated at the meetings. The meetings provided participants with almost continuous services. Sermons of great power were the rule, in contrast to the staid ceremony of many established Eastern chruches, and speakers competed with each other in skill, enthusiasm, and ability to be heard by the large crowds. Once one speaker was finished, often after several hours, another would often rise to take his place. Singing would break the monotony of the sermons, and many simple but powerful hymns resulted.

Without a regular choir or hymnals, camp meeting songs tended to be extremely simple and easy to learn, with choruses often consisting of only a few words. The family words, "Yes, Jesus love me!" (repeated three times) followed by "The Bible tells me so," are a typical example. Lyrics were often printed on special "songsters" for camp meetings, but were seldom relied on, as many could not read, and a successful song session emphasized spontaneity, enthusiasm and repitition. Negro spirituals, with their call-and-response format, thus entered the mainstream of white worship tradition through the medium of the camp meeting. The song leader would typically sing a short verse with varied words, and the congregation would answer the refrain, as in (leader): "I'm gonna lay down my sword and shield," (congregation): "Down by the Riverside, Down By the Riverside, Down by the Riverside!" Song like "Shall We Gather by the River," "Amazing Grace," and several of the songs from the Methodist hymnal also came to be perennial favorites.

History

The Pennsylvania-born Presbyterian minister James McGready (c. 1758-1817) organized the first known major series of camp meeting in Logan County, Kentucky from 1797-99, begging a major religious revival that swept through the frontier county of the American South and West at the turn of the nineteenth century. Soon, dozens of preachers were crossing the country holding camp meetings. The meetings thus became a major contributing factors to what became known as the Second Great Awakening.

A particularly large and successful meeting was held at Cane Ridge, Kentucky in 1801, where the Restoration Movement began to be formalized. In Georgia, the first recorded camp meeting has held on Shoulderbone Creek in Hancock County 1803. English Methodist preacher Lorenzo Dow was greatly moved by the event, and took the concept back to England, where it led eventually to the formation of the Primitive Methodist tradition.

In 1815, in what is now Toronto, Ohio, Reverend J. M. Bray, pastor of the Sugar Grove Methodist Episcopal Church, began an annual camp meeting that still meets today as the Hollow Rock Holiness Camp Meeting Association.

The meetings became more professionally organized in time and gained wide recognition, as well as a substantial increase in popularity, in the aftermath of the American Civil War as a result of the first Holiness movement camp meeting in Vineland, New Jersey in 1867. Ocean Grove, New Jersey, founded in 1869, has been called the "Queen of the Victorian Methodist Camp Meetings." At the end of the nineteenth century, believers in Spiritualism also established camp meetings throughout the United States.

Camp meetings in America continued to be conducted for many years on a wide scale. Some are still held today, primarily by Pentecostal groups. The contemporary revival meeting—held either in a local church, auditorium or tent—is often seen as a modern-day attempt to recreate the spirit and effectiveness of the frontier camp meeting.

Camp meetings in British Methodism

Lorenzo Dow brought reports of Camp Meetings from America during his visits to England. Hugh Bourne, William Clowes and Daniel Shoebotham saw this as an answer to complaints from members of the Harriseahead Methodists that their weeknight prayer meeting was too short. Bourne also saw these as an antidote to the general debauchery of the Wakes in that part of the Potteries, one of the reasons why he continued organising Camp Meetings in spite of the opposition from the Wesleyan authorities.

May 1807 the first camp meeting in England was held at Mow Cop. The Wesleyan Methodists disapproved of the event and subsequently expelled organizer Hugh Bourne "because you have a tendency to set up other than the ordinary worship." His expulsion led eventually to the formation of the Primitive Methodist Church.

The pattern of the Primitive Methodist Camp Meeting was as a time of prayer and preaching from the Bible. In the first Camp Meeting, 4 separate "preaching stations" had been set up by the afternoon, each with an audience, while in between others spent the time praying. Their emphasis on the Bible is a clear distinction from the spiritualist strand of American camp meetings.

From May 1807 to the establishing of Primitive Methodism as a denomination in 1811, a series of 17 Camp Meetings was held.[1] There were a number of different venues beyond Mow Cop, including Norton-in-the-Moors during the Wakes in 1807 (Hugh Bourne's target venue), and Ramsor in 1808.

After Hugh Bourne and a significant number of his colleagues, including the Standley Methodist Society, had been put out of membership of the Burslem Wesleyan Circuit, they formed a group known as the Camp Meeting Methodists until 1811 when they joined with the followers of William Clowes, the "Clowesites".

Camp Meetings were a regular feature of Primitive Methodist life throughout the 19th century,[2] and still have existence in other forms today. The annual late May Bank Holiday weekend meetings at Cliff College[3] are one example, with a number of tents around the site, each with a different preacher.

Notes

- ↑ H B Kendall, “The Origin and History of the Primitive Methodist Church”, (1906 for the 1907 Camp Meeting Centenary), p. 89 ISBN 1901670-49-X ISBN 9781901670-49-3 (EAN-13 format)

- ↑ Continued mention in Circuit Plans and the Minutes of Circuit Meetings

- ↑ Cliff College is a Methodist training college in Derbyshire. The meetings are an annual attraction for many Methodists.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Paul Gillespie and his students (editors), Foxfire 7, Anchor Books, New York 1980, ISBN 0-385-15244-2

- Moore, William D., 1997. "'To Hold Communion with Nature and the Spirit-World:' New England's Spiritualist Camp Meetings, 1865-1910." In Annmarie Adams and Sally MacMurray, eds. Exploring Everyday Landscapes: Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture, VII. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 0-87049-983-1.

- George Rawlyk The Canada Fire: Radical Evangelicalism in British North America, 1775-1812. McGill-Queen's UP, 1994.

- The 20th century American composer Charles Ives used the Camp Meeting phenomenon as a metaphysical basis for his Symphony No. 3 (Ives). Although the piece wasn't initially performed until almost 40 years after its composition in 1946, it did succeed in winning the Pulitzer Prize the following year in 1947.

External links

- Christian Camp and Conference Association

- Journal of Methodist itinerant Nathan Bangs (1778–1862) recounting the first camp meeting held in Upper Canada in 1805

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.