Bloom, Benjamin

| Line 5: | Line 5: | ||

'''Benjamin Bloom''' (February 21, 1913 - September 13, 1999) was an [[United States|American]] [[educational psychology|educational psychologist]] who made significant contributions to the classification of educational objectives and the theory of [[mastery learning]]. | '''Benjamin Bloom''' (February 21, 1913 - September 13, 1999) was an [[United States|American]] [[educational psychology|educational psychologist]] who made significant contributions to the classification of educational objectives and the theory of [[mastery learning]]. | ||

==Life== | ==Life== | ||

| + | Benjamin S. Bloom was born on 21 February 1913 in Lansford, Pennsylvania, and | ||

| + | died on 13 September 1999. He received a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Pennsylvania | ||

| + | State University in 1935 and a Ph.D. in Education from the University of Chicago in March | ||

| + | 1942. He became a staff member of the Board of Examinations at the University of Chicago | ||

| + | in 1940 and served in that capacity until 1943, at which time he became university examiner, | ||

| + | a position he held until 1959. | ||

| + | |||

| + | He served as educational adviser to the governments of Israel, India and numerous other nations. | ||

| + | |||

| + | What Bloom had to offer his students was a model of an inquiring scholar, someone who embraced | ||

| + | the idea that education as a process was an effort to realize human potential, indeed, even | ||

| + | more, it was an effort designed to make potential possible. Education was an exercise in | ||

| + | optimism. Bloom’s commitment to the possibilities of education provided for many who | ||

| + | studied with him a kind of inspiration.<ref>Elliot W. Eisner, ''Benjamin Bloom'', Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education, Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXX, no. 3, September 2000.</ref> | ||

==Work== | ==Work== | ||

| Line 14: | Line 28: | ||

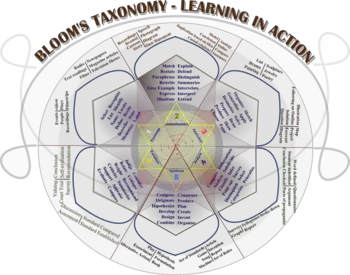

Benjamin Bloom headed a group of Cognitive psychologists at the University of Chicago who developed a taxonomic hierarchy of cognitive-driven behavior deemed to be important to learning and measurable capability. For example, an objective that begins with the verb "describe" is measurable but one that begins with the verb "understand" is not. | Benjamin Bloom headed a group of Cognitive psychologists at the University of Chicago who developed a taxonomic hierarchy of cognitive-driven behavior deemed to be important to learning and measurable capability. For example, an objective that begins with the verb "describe" is measurable but one that begins with the verb "understand" is not. | ||

| − | His classification of educational objectives, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain (Bloom et al., 1956), addresses cognitive domain versus the psychomotor and affective domains of knowledge. Bloom’s [[taxonomy]] provides structure in which to categorize instructional objectives and instructional assessment. | + | His classification of educational objectives, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain (Bloom et al., 1956), addresses cognitive domain versus the psychomotor and affective domains of knowledge. It was designed to provide a more reliable procedure for assessing students and the outcomes of educational practice. Bloom’s [[taxonomy]] provides structure in which to categorize instructional objectives and instructional assessment . His taxonomy was designed to help teachers and Instructional Designers to classify instructional objectives and goals. The foundation of his taxonomy was based on the idea that not all learning objectives and outcomes are equal. For example, memorization of facts, while important, is not the same as the learned ability to analyze or evaluate. In the absence of a classification system (i.e., a taxonomy), teachers and Instructional Designers may choose, for example, to emphasize memorization of facts (which make for easier testing) than emphasizing other (and likely more important) learned capabilities. |

Bloom’s taxonomy in theory helps teachers better prepare objectives and, from there, derive appropriate measures of learned capability.The fact is that most teachers have very little understanding of the meaning and intent of Bloom's Taxonomy (or subsequent taxonomys). Curriculum design, which is usually a State (i.e., governmental) practice, has not reflected the intent of such a taxonomy until the late 1990s. It is worth noting that Bloom was an American Academic and that his constructs will not be universally embraced. | Bloom’s taxonomy in theory helps teachers better prepare objectives and, from there, derive appropriate measures of learned capability.The fact is that most teachers have very little understanding of the meaning and intent of Bloom's Taxonomy (or subsequent taxonomys). Curriculum design, which is usually a State (i.e., governmental) practice, has not reflected the intent of such a taxonomy until the late 1990s. It is worth noting that Bloom was an American Academic and that his constructs will not be universally embraced. | ||

Revision as of 20:56, 12 December 2007

Benjamin Bloom (February 21, 1913 - September 13, 1999) was an American educational psychologist who made significant contributions to the classification of educational objectives and the theory of mastery learning.

Life

Benjamin S. Bloom was born on 21 February 1913 in Lansford, Pennsylvania, and died on 13 September 1999. He received a bachelor’s and master’s degree from Pennsylvania State University in 1935 and a Ph.D. in Education from the University of Chicago in March 1942. He became a staff member of the Board of Examinations at the University of Chicago in 1940 and served in that capacity until 1943, at which time he became university examiner, a position he held until 1959.

He served as educational adviser to the governments of Israel, India and numerous other nations.

What Bloom had to offer his students was a model of an inquiring scholar, someone who embraced the idea that education as a process was an effort to realize human potential, indeed, even more, it was an effort designed to make potential possible. Education was an exercise in optimism. Bloom’s commitment to the possibilities of education provided for many who studied with him a kind of inspiration.[1]

Work

Bloom's theory

Benjamin Bloom was an influential academic Educational Psychologist. His main contributions to the area of education involved mastery learning, his model of talent development, and his Taxonomy of Educational Objectives in the cognitive domain.

He focused much of his research on the study of educational objectives and, ultimately, proposed that any given task favours one of three psychological domains: cognitive, affective, or psychomotor. The cognitive domain deals with our ability to process and utilize (as a measure) information in a meaningful way. The affective domain is concerned with the attitudes and feelings that result from the learning process. Lastly, the psychomotor domain involves manipulative or physical skills.

Benjamin Bloom headed a group of Cognitive psychologists at the University of Chicago who developed a taxonomic hierarchy of cognitive-driven behavior deemed to be important to learning and measurable capability. For example, an objective that begins with the verb "describe" is measurable but one that begins with the verb "understand" is not.

His classification of educational objectives, Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive Domain (Bloom et al., 1956), addresses cognitive domain versus the psychomotor and affective domains of knowledge. It was designed to provide a more reliable procedure for assessing students and the outcomes of educational practice. Bloom’s taxonomy provides structure in which to categorize instructional objectives and instructional assessment . His taxonomy was designed to help teachers and Instructional Designers to classify instructional objectives and goals. The foundation of his taxonomy was based on the idea that not all learning objectives and outcomes are equal. For example, memorization of facts, while important, is not the same as the learned ability to analyze or evaluate. In the absence of a classification system (i.e., a taxonomy), teachers and Instructional Designers may choose, for example, to emphasize memorization of facts (which make for easier testing) than emphasizing other (and likely more important) learned capabilities.

Bloom’s taxonomy in theory helps teachers better prepare objectives and, from there, derive appropriate measures of learned capability.The fact is that most teachers have very little understanding of the meaning and intent of Bloom's Taxonomy (or subsequent taxonomys). Curriculum design, which is usually a State (i.e., governmental) practice, has not reflected the intent of such a taxonomy until the late 1990s. It is worth noting that Bloom was an American Academic and that his constructs will not be universally embraced.

A good example of the application of 'a' Taxonomy of Educational Objectives is in the curriculum of the Canadian Province of Ontario which provides for its teachers an integrated adaptation of Bloom's taxonomy. Ontario's Ministry of Education taxonomic categories are: Knowledge and Understanding; Thinking; Communication; Application. Every 'specific' learning objective, in any given course, can be classified according to the Ministry's taxonomy. However, Ontario's Ministry of Education failing is that it has not provided teachers with a reliable and systematic means for classifying the prescribed educational objectives. In fact, it would have been appropriate for the Ministry to classify the objectives in advance and thereby avoid confusion because taxonomic classification is not intuitive. Hence, while Bloom's Taxonomy is valid in theory, it can be rendered meaningless at the implementation stage.

Decade of dedication

In 1985 Bloom conducted a study suggesting that at least 10 years of hard work (a "decade of dedication"), regardless of genius or natural prodigy status, is required to achieve recognition in any respected field.[2] This shows starkly in Bloom's 1985 study of 120 elite athletes, performers, artists, biochemists and mathematicians. Every single person in the study took at least a decade of hard study or practice to achieve international recognition. Olympic swimmers trained for an average of 15 years before making the team; the best concert pianists took 15 years to earn international recognition. Top researchers, sculptors and mathematicians put in similar amounts of time.

Taxonomy of educational objectives

The Taxonomy of Educational Objectives, often called Bloom's Taxonomy, is a classification of the different objectives and skills that educators set for students (learning objectives). The taxonomy was proposed in 1956 by Benjamin Bloom, an educational psychologist at the University of Chicago. Bloom's Taxonomy divides educational objectives into three "domains:" Affective, Psychomotor, and Cognitive. Like other taxonomies, Bloom's is hierarchical, meaning that learning at the higher levels is dependent on having attained prerequisite knowledge and skills at lower levels (Orlich, et al. 2004). A goal of Bloom's Taxonomy is to motivate educators to focus on all three domains, creating a more holistic form of education.

Most references to the Bloom's Taxonomy only notice the Cognitive domain. There is also a so far less referred, revised version of the Taxonomy, published in 2001 under the name of "A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and assessing," eds. Anderson, Lorin W., Krathwohl, David R., Airasian, Peter W., Cruikshank, Kathleen A., Mayer, Richard E., Pintrich, Paul R., Raths, James and Wittrock, Merlin C.

Affective

Skills in the affective domain describe the way people react emotionally and their ability to feel another living thing's pain or joy. Affective objectives typically target the awareness and growth in attitudes, emotion, and feelings.

There are five levels in the affective domain moving through the lowest order processes to the highest:

- Receiving

- The lowest level; the student passively pays attention. Without this level no learning can occur.

- Responding

- The student actively participates in the learning process, not only attends to a stimulus, the student also reacts in some way.

- Valuing

- The student attaches a value to an object, phenomenon, or piece of information.

- Organizing

- The student can put together different values, information, and ideas and accommodate them within his/her own schema; comparing, relating and elaborating on what has been learned.

- Characterizing

- The student has held a particular value or belief that now exerts influence on his/her behaviour so that it becomes a characteristic.

Psychomotor

Skills in the psychomotor domain describe the ability to physically manipulate a tool or instrument like a hand or a hammer. Psychomotor objectives usually focus on change and/or development in behavior and/or skills.

Bloom and his colleagues never created subcategories for skills in the psychomotor domain, but since then other educators have created their own psychomotor taxonomies[3].

Cognitive

Skills in the cognitive domain revolve around knowledge, comprehension, and "thinking through" a particular topic. Traditional education tends to emphasize the skills in this domain, particularly the lower-order objectives.

There are six levels in the taxonomy, moving through the lowest order processes to the highest:

- Knowledge

- Exhibit memory of previously-learned materials by recalling facts, terms, basic concepts and answers

- Knowledge of specifics - terminology, specific facts

- Knowledge of ways and means of dealing with specifics - conventions, trends and sequences, classifications and categories, criteria, methodology

- Knowledge of the universals and abstractions in a field - principles and generalizations, theories and structures

Questions like: What is...?

- Comprehension

- Demonstrative understanding of facts and ideas by organizing, comparing, translating, interpreting, giving descriptions, and stating main ideas

- Translation

- Interpretation

- Extrapolation

Questions like: How would you compare and contrast...?

- Application

- Using new knowledge. Solve problems to new situations by applying acquired knowledge, facts, techniques and rules in a different way

Questions like: Can you organize _______ to show...?

- Analysis

- Examine and break information into parts by identifying motives or causes. Make inferences and find evidence to support generalizations

- Analysis of elements

- Analysis of relationships

- Analysis of organizational principles

Questions like: How would you classify...?

- Synthesis

- Compile information together in a different way by combining elements in a new pattern or proposing alternative solutions

- Production of a unique communication

- Production of a plan, or proposed set of operations

- Derivation of a set of abstract relations

Questions like: Can you predict an outcome?

- Evaluation

- Present and defend opinions by making judgments about information, validity of ideas or quality of work based on a set of criteria

- Judgments in terms of internal evidence

- Judgments in terms of external criteria

Questions like: Do you agree with.....?

Some critique on Bloom's Taxonomy('s cognitive domain) admit the existence of these six categories, but question the existence of a sequential, hierarchical link (Paul, R. (1993). Critical thinking: What every person needs to survive in a rapidly changing world (3rd ed.). Rohnert Park, California: Sonoma State University Press.). Also the revised edition of Bloom's taxonomy has moved Synthesis in higher order than Evaluation. Some consider the three lowest levels as hierarchically ordered, but the three higher levels as parallel. Others say that it is sometimes better to move to Application before introducing Concepts. This thinking would seem to relate to the method of Problem Based Learning.

Major publications

- Bloom, Benjamin S. (1980). All Our Children Learning. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Bloom, Benjamin S. Taxonomy of Educational Objectives. Published by Allyn and Bacon, Boston, MA. Copyright (c) 1984 by Pearson Education.

Notes

- ↑ Elliot W. Eisner, Benjamin Bloom, Prospects: the quarterly review of comparative education, Paris, UNESCO: International Bureau of Education), vol. XXX, no. 3, September 2000.

- ↑ David Dobbs, "How to be a genius," The New Scientist Online Magazine, Sept. 15, 2005.

- ↑ http://www.nwlink.com/~donclark/hrd/bloom.html

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Taxonomy of Educational Objectives: The Classification of Educational Goals; pp. 201-207; B. S. Bloom (Ed.) Susan Fauer Company, Inc. 1956.

- A Taxonomy for Learning, Teaching, and Assessing—A Revision of Bloom's Taxonomy of Educational Objectives; Lorin W. Anderson, David R. Krathwohl, Peter W. Airasian, Kathleen A. Cruikshank, Richard E. Mayer, Paul R. Pintrich, James Raths and Merlin C. Wittrock (Eds.) Addison Wesley Longman, Inc. 2001

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.