Max Schmeling

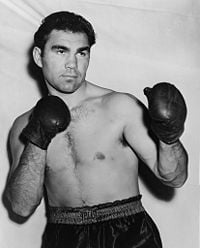

| Max Schmeling | |

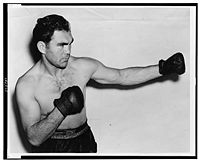

Max Schmeling 1938 | |

| Statistics | |

|---|---|

| Real name | Maximillian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling |

| Nickname | Black Uhlan of the Rhine |

| Rated at | Heavyweight |

| Nationality | |

| Birth date | September 28, 1905 |

| Birth place | Uckermark, Germany |

| Death date | February 2, 2005 |

| Stance | Orthodox |

| Boxing record | |

| Total fights | 70 |

| Wins | 56 |

| Wins by KO | 40 |

| Losses | 10 |

| Draws | 4 |

| No contests | 0 |

Maximillian Adolph Otto Siegfried Schmeling (September 28, 1905 â February 2, 2005) was a world champion heavyweight fighter from Germany whose two fights with Joe Louis transcended boxing and became worldwide political events because of their racial and international importance.

After rising to the top of the heavyweight ranks, Schmeling fought a famous non-title fight with the previously undefeated Louis in 1936, knocking the 22-year-old African-American fighter down in the fourth round and finishing him off in the twelfth. Schmeling's title and image were used as a propaganda tool by Adolf Hitler to demonstrate Aryan supremacy. However, despite his associations with Nazism, after the Second World War it was revealed that Schmeling had risked his own life to save the lives of two Jewish children in 1938.

When Louis later won the title, a rematch was scheduled for 1938; a bout that caught the imagination of the world as a contest between the Nazi philosophy of racial superiority and the American value of egalitarianism. Louis knocked out Schmeling in the first round.

Schmeling served as a German paratrooper during World War II and resumed his career when the war ended. He fought until 1948 before retiring, becoming and remaining a personal friend of Louis, his former nemesis. Besides being a top heavyweight of his era, he remains a symbol of both the former intense enmity and the later friendship between Germany and the United States.

Boxing career

Early years and Jack Sharkey

Schmeling debuted as a professional boxer in 1924, and he built a record of 42 wins, four losses, and three draws, before being given a title shot. He won the German light-heavyweight title in 1926 and also won the European 175-pound title and German heavyweight crown before coming to the United States to fight. In 1929 in New York, Schmeling defeated a pair of top heavyweightsâJohnny Risko and Paolino Uzcudunâearning him a number-two ranking and a shot at the heavyweight title.

Schmeling finally fought Jack Sharkey for the vacant world heavyweight championship in 1930 in Yankee Stadium. In round four, Sharkey hit Schmeling with a low blow so severe that Schmeling could not continue. Thus, Schmeling won the world title on a disqualification. He remains the only heavyweight world champion to win the title on a disqualification. In 1931, he defended his title successfully, knocking out Young Stribling in 15 rounds at Cleveland. In 1932, Schmeling and Sharkey had a rematch. After 15 rounds, Sharkey was declared the winner on points (a controversial split decision), and Schmeling lost the title. This decision led to Joe Jacobs, his manager, shouting in protest a line that since has become famous: "We was robbed!"

Three months after he lost the title, Schmeling knocked out Mickey Walker, proving to many that he was still the world's best heavyweight. That changed in June 1933 when he lost by T.K.O. against later champion Max Baer at Yankee Stadium. American fight fans considered Schmeling to be a Nazi fighter representing Hitler's Germany, while Baer, who was Jewish, displayed an embroidered Star of David on his trunks. Baer dominated the rugged fighter from Germany into the tenth round when the referee stopped the match.

Despite efforts to make a third fight between Schmeling and Sharkey happen, the rubber match never took place.

The Joe Louis fights

In 1936, Schmeling came to New York to face the up-and-coming African-American boxer Joe Louis, who was undefeated and considered unbeatable. Upon his arrival, Schmeling claimed that he had found a flaw in Louis' style, observing the way in which he dropped his guard after throwing a punch. He surprised the boxing world by handing Louis his first defeat, dropping him in round four and knocking him out in the twelfth. Schmeling returned to Germany on the Hindenburg as a hero.

Louis and his mainly black supporters were devastated by the defeat. Schmeling, himself, was also affected. When Louis finally won the world heavyweight crown in 1937, he said he would not consider himself a champion until he beat Schmeling in a rematch.

The famous rematch came, at Yankee Stadium, on June 22, 1938, with Louis defending his crown. By then, a second world war was clearly looming on the horizon, and the fight was viewed worldwide as symbolic battle for superiority between two likely adversaries and a test of the Nazi theory of Aryan racial superiority. In American pre-fight publicity, Schmeling was cast as the Nazi warrior, while Louis was portrayed as a defender of American ideals.

The rematch did not last long, however, as Louis scored a devastating first-round knockout.

The fight was broadcast by radio all over the United States and Europe. Some accounts claim that after Louis dropped Schmeling for the first time, Joseph Goebbels ordered that the broadcast of the fight to Germany be cut off, a claim that his since been refuted. [1] In 2005 the fight was selected for permanent preservation in the National Recording Registry at the Library of Congress.

When Louis retained his title, Hitler took Schmeling's defeat as an embarrassment to his country. While he was never a supporter of the Nazi regime in Germany, Schmeling cooperated briefly with the German government's efforts to play down the negative international world view of its domestic policies during the 1930s.

One year after that defeat against Louis, Max Schmeling rebounded as a fighter by winning the European Heavyweight Title.

Debatable "Nazi" label

Schmeling was branded as a "Nazi" by many boxing fans, but he became quite unpopular among the Nazis after the embarrassing loss to Louis. Schmeling claimed it was a relief to him when he was not used further in Nazi propaganda. His history does not reveal him to have been an anti-Semite. Indeed, in 1928, he hired Joe Jacobs, a Jew, to be his manager. He would point to this fact for the rest of his life in defending himself against charges of Nazi sympathy.

More telling, in 1938, during the the anti-Jewish Nazi-organized riots of Kristallnacht, Schmeling hid two teenage sons of a Jewish friend in his Berlin hotel room, protecting them from the SS and Gestapo at great risk to himself. The two boys, Henry and Werner Lewin, were eventually smuggled out of Germany with Schmeling's help.

When World War II broke out in 1939, Schmeling was drafted into the German Wehrmacht and served as a paratrooper. Following its end he was interned briefly by the Allies, still recovering from injuries sustained in the war. Afterwards, he frequently visited American troops, giving away signed photos and taking pictures with the American soldiers.

Retirement years and death

The early postwar years were financially difficult for Schmeling. However, when a former New York boxing commissioner who had become a Coca-Cola executive offered him the postwar soft drink franchise in Germany, he became a successful businessman and one of Germany's most respected philanthropists. At his death, he was still one of the owners of Coca-Cola's German branch.

After 1948, Schmeling had retired from boxing. He and Louis became friends following a 1954 meeting on the U.S. television program This Is Your Life. Schmeling and Louis met 12 times afterward as friends, and when Louis found himself impoverished in later life, Schmeling helped to pay Louis' medical bills. He was also one of the pallbearers at Louis's funeral in 1981.

Until shortly before his death, Schmeling made several trips a year around the world to attend activities related to his boxing career.

After celebrating his ninety-ninth birthday in 2004, Schmeling vowed to live on to celebrate his hundredth. However, that Christmas, he came down with a bad cold, and his health never recovered. He slipped into a coma on January 31, 2005, and died two days later at 3:55 pm. He was buried next to his wife, the Austro-Hungarian-born Czech film actress Anny Ondra (Anna Sophie OndrĂĄkovĂĄ), to whom he was married for 54 years. They had no children.

Legacy

Besides being a great fighter, Max Schmeling's finest legacy may very well be how he lived outside the ring. He saved the lives of innocent children at great risk to himself during the Nazi era; became lifelong friends with Joe Louis, even helping him financially in his old age; entertained American soldiers; and worked as a businessman to restore his homeland.

During his fighting career he was:

- German Light heavyweight Champion 1926-1928

- European Light heavyweight Champion 1927-1928

- German Heavyweight Champion 1928

- World Heavyweight Champion 1930-1932

- European Heavyweight Champion 1939-1943

Schmeling compiled a lifetime record of 56 wins, 10 losses, and four draws with 40 wins by knockout. He was inducted into the International Boxing Hall Of Fame in 1992 and is an Honorary Citizen of the cities of Los Angeles, Las Vegas, and his hometown, of Klein-Luckow.

He has been the object of several books, including a biography, and in 2001, STARZ! produced a movie about him and Louis named Joe and Max. He is recognized as one of the top heavyweights of his era and remains a symbol both of the animosity between Germany and America during the WWII era and of the reconciliation and friendship between the two countries in its aftermath.

Notes

- â German sports writer with the Associated Press, Roy Kammerer, based in Berlin, wrote in 2005: "The fight was a huge event worldwide and left a lasting impression on his era of Germans, who followed blow-by-blow on radio." Kammerers account is supported by a July 3, 1988 letter to the Sports Editor of the New York Times from Ludwig Stein of Chappaqua, N.Y. claiming that he heard the entire fight on German radio as a 13-year-old.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Cayton, Bill. Joe Louis Vs. Max Schmeling. (Audio CD), Cayton Sports, 2001. ISBN 978-0970837127

- Margolick, David. Beyond Glory: Joe Louis Vs. Max Schmeling, and a World on the Brink. Vintage, 2006. ISBN 978-0375726194

- Myler, Patrick. Ring of Hate: Joe Louis Vs. Max Schmeling: The Fight of the Century. Arcade Publishing, 2006.

- Von Der Lippe, George. Max Schmeling: An Autobiography. Bonus Books, 1998. ISBN 978-1566251082

External links

All links retrieved April 29, 2025.

- PBS biography of Max Schmeling www.pbs.org.

- The Fight of the Century: Louis vs. Schmeling NPR special on the selection of the radio broadcast to the 2005 National Recording Registry. www.npr.org.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.