Idi Amin

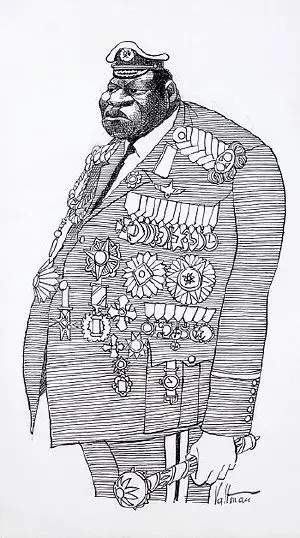

Idi Amin Dada (mid-1920s – August 16, 2003) was President of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. His reign was characterized by human rights abuses, political repression, sectarian violence, and ethnic persecution, in particular with the expulsion of Asians from Uganda, and persecution of the Acholi people and Lango ethnic groups. The death toll during Amin's regime probably will never be accurately known; estimates range from 80,000 to as high as 500,000. Amin styled himself His Excellency, President of Uganda, President President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji, Doctor Idi Amin, VC, Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular.

When he assumed power in 1971, Uganda had experienced a series of coups and counter coups since achieving independence in 1962. Amin sincerely believed that his coup enjoyed popular support, while his promise to improve the economy, schools, health care and to raise the standard of living generated some enthusiasm. Cheering crowds were reported in the streets of Kampala after the coup. His charismatic personality exuded confidence in the ability of an African state, led by an African leader, to put its own house in order. Unfortunately, Amin's habit of blaming everything that was wrong in Uganda on the former colonial power wore thin as he accumulated personal wealth, ordered anyone who opposed him killed. He made no effort to establish a democratic, civilian government.

What was meant to be a short-term, caretaker government lasted eight years. Like many dictators, he argued that the measures he initially put in place were necessary to restore law and order. He never rescinded them. It is possible that the potential economic rewards of the Presidency were too attractive for a man who boasted about the poverty of his upbringing. The life he began to lead appears to have resulted in mental instability. Some allege that he suffered from syphilis.

Amin, at the beginning, had Uganda's interests at heart. However, he lacked the skill to achieve the reforms he wanted and what started with a degree of hope, like dictatorial careers elsewhere, turned into a nightmare for his people.

Early life

Amin never wrote an autobiography, nor authorized any to be written. There are discrepancies as to when and where he was born. Biographical sources usually hold that he was born in Koboko or Kampala around about 1925. Unconfirmed sources state Amin's year of birth from as early as 1923 to as late as 1928. Amin's son Hussein has stated that his father was born in Kampala in 1928.[1]

According to Fred Guweddeko, a researcher at Makerere University, Idi Amin was fathered by Andreas Nyabire (1889–1976). Nyabire was an ethnic Kakwa and Roman Catholic Church who converted to Islam in 1910 and changed his name to Amin Dada. Abandoned by his father, Amin grew up with his maternal family. Guweddeko states that Amin's mother was called Assa Aatte (1904–1970), an ethnic Lugbara and a traditional herbalist, who among others treated members of Buganda royalty. Amin joined an Islamic school in Bombo, Uganda in 1941, where he excelled in reciting the Qur'an. After a few years he left the school, and did odd jobs before being recruited to the army by a British colonial army officer.[2]

Military career

Colonial British army

Amin joined the King's African Rifles (KAR) of the British Colonial Army in 1946 as an assistant cook. He claimed he was forced to join the Army during World War II, and that he served in the Burma Campaign, but this is disputed as records indicate he was first enlisted after the war was concluded.[3]

He transferred to Kenya for infantry service as a Private (rank) in 1947, and served in the 21st KAR infantry brigade in Gilgil, Kenya, until 1949 when his unit was deployed in Somalia to fight the Somali Shifta rebels who were cattle raiding|rustling cattle.[4] In 1952 his battalion was deployed against the Mau Mau rebels in Kenya. He was promoted to corporal the same year, then to sergeant in 1953.[2]

In 1954 Amin was made effendi (Warrant officer), the highest rank possible for a Black African in the Colonial British Army. He returned to Uganda the same year. In 1961 he became one of the first two Ugandans to become Officer (armed forces)|Commissioned Officers with the rank of Lieutenant. He was then assigned to quell the cattle rustling between Uganda's Karamojong and Kenya's Turkana nomads. He was promoted to captain in 1962, and major in 1963. The following year, Amin was appointed to Deputy Commander of the Army.[2]

During his time in the army, the 193 cm (6'4") physically imposing Idi Amin was the Ugandan light heavyweight boxing champion from 1951 to 1960, as well as a swimmer and rugby player.[5]

| Chronology of Amin's military promotions | |

| King's African Rifles | |

| 1946 | Joins King's African Rifles |

| 1947 | Private |

| 1952 | Corporal |

| 1954 | Effendi (Warrant Officer) |

| 1961 | First Ugandan Commissioned Officer, Lieutenant |

| Uganda Army | |

| 1962 | Captain |

| 1963 | Major |

| 1964 | Deputy Commander of the Army |

| 1965 | Colonel, Commander of the Army |

| 1968 | Major General |

| 1971 | Head of State Chairman of the Defence Council Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces Army Chief of Staff and Chief of Air Staff |

| 1975 | Field Marshal |

Army Commander

In 1965 Prime Minister Milton Obote and Amin were implicated in a deal to smuggle ivory and gold into Uganda from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. The deal, as later alleged by General Nicholas Olenga, an associate of the former Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba, was part of an arrangement to help troops opposed to the Congolese government trade ivory and gold for arms supplies secretly smuggled to them by Amin. In 1966, Parliament demanded an investigation. Obote imposed a new constitution abolishing the ceremonial presidency held by Kabaka (King) Edward Mutesa II of Buganda, and declaring himself executive president. He promoted Amin to Colonel and Army Commander. An attack on the Kabaka's palace, led by Amin, forced Mutesa into exile to the United Kingdom where he remained until his death in 1969.

Amin began recruiting members of Kakwa, Lugbara, and other ethnic groups from the West Nile sub-region bordering Sudan. Nubians were also recruited into the Ugandan army. The Nubians in question had been resident in Uganda since the early twentieth century, having been brought from Sudan to serve the colonial army. In Uganda, Nubians were commonly perceived as Sudanese foreigners, and erroneously referred to as "Anyanya" (Anyanya were southern Sudanese rebels of the First Sudanese Civil War and were not involved in Uganda). Allegations still persist that Idi Amin's army consisted substantially of Sudanese soldiers — a misconception resulting from the reality that many ethnic groups in Northern Uganda inhabit both Uganda and Sudan.[6]

Seizure of power

A number of factors - including the support Amin had built within the army by recruiting from the West Nile region, his involvement in operations to support the rebellion in southern Sudan, and the attempted assassination of Obote in 1969 - eventually led to a rift between Amin and Obote. In October 1970, Obote himself took control of the armed forces, reducing General Amin from the post of commander of all the armed forces - which he had held for only a few months - to that of Commander of the Army. After hearing that Obote was planning to arrest him for misappropriating army funds, Amin seized power in a 1971 Ugandan military coup on 25 January 1971, while Obote was attending a Commonwealth of Nations summit meeting in Singapore.[7]

Troops loyal to Amin sealed off Entebbe airport, the main international airport, and took control of Kampala. Obote's residence was surrounded, and major roads were blocked. A broadcast on Radio Uganda accused Obote's government of corruption, and for giving preferential treatment to the Lango region. Cheering crowds were reported in the streets of Kampala after the radio broadcast.[8] Amin announced that he was a soldier, not a politician, and that the military government would remain only as a caretaker regime until new elections, which would be announced as soon as the situation was normal. He also promised to release all political prisoners.[9]

Idi Amin was initially welcomed both within Uganda and by the international community. In an internal memo, the British Foreign Office described him as "A splendid type and a good football player".[10] He gave former king and president Mutesa (who had died in exile) a state burial in April 1971, freed many political prisoners, and reiterated his promise to hold free and fair elections to return the country to democratic rule in the shortest period possible.

Amin's rule

Establishment of military rule

On February 2, 1971, one week after the coup, Amin declared himself president of Uganda, Commander-in-Chief of the armed forces, Army Chief of staff (military) and Chief of Air Staff. He announced that certain provisions of the Constitution of Uganda had been suspended, and soon instituted an advisory Defence Council composed of military officers, with himself as the chairman. Military tribunals were placed above the system of civil law, soldiers were appointed to top government posts and parastatal agencies, and the newly inducted civilian cabinet ministers were informed that they would be subject to military discipline. [11] The presidential lodge in Kampala, known as Government House, was renamed to "the Command Post." He disbanded the General Service Unit (GSU), an intelligence agency created by the previous government, and replaced it with the State Research Bureau (SRB). SRB headquarters at Nakasero became the scene of torture and executions over the next several years. Other agencies used to root out political dissent included the Military Police and the Public Safety Unit (PSU).[11]

Obote took refuge in Tanzania, having been offered sanctuary there by Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere. He was soon joined by 20,000 Ugandan refugees fleeing Amin.[12] In 1972, the exiles attempted to regain the country through a military invasion, without success.[5]

Persecution of ethnic and other groups

In retaliation to the attempted invasion by Ugandan exiles in 1972, Amin began purging the army of Obote supporters – predominantly those from the Acholi and Lango ethnic groups. [5] In July 1971, Lango and Acholi soldiers were massacred in the Jinja and Mbarara Barracks and by early 1972 some 5,000 Acholi and Lango soldiers, and at least twice as many civilians had disappeared.[13] The victims soon came to include members of other ethnic groups, as well as religious leaders, judges, lawyers, students and intellectuals, criminal suspects, and foreign nationals. This created conditions in which many other people were killed for criminal motives or simply at will. Bodies were dumped into the River Nile, on at least one occasion in quantities sufficient to clog the Owen Falls hydro-electric Dam in Jinja.[14]

The killings, for ethnic, political, and financial reasons, continued throughout Amin's eight-year reign.[13] The exact number of people killed is unknown. The International Commission of Jurists estimated the death toll at not less than 80,000 and more likely around 300,000. An estimate compiled by exile organizations with the help of Amnesty International, put the number killed at 500,000.[3]

In 1977 the first from-the-inside exposé of Amin's rule was published. Henry Kyemba, Amin's Health Minister and a former official of the first Obote regime, defected and resettled in Britain. Kyemba wrote and published A State of Blood, which gave an in-depth account of Amin's rule.

Expulsion of Asians

In August 1972, Idi Amin declared what he called "Economic war," a set of policies which included the expropriation of properties owned by Asians and Europeans who he accused of living off Uganda's wealth while Africans suffered hardship. He saw the Asian community as a relic of colonialism. Uganda's Asians, who numbered 80,000, were mostly Indians born in the country, their ancestors having come from India to Uganda when the country was still a British colony. Many owned businesses, including large-scale enterprises, forming the backbone of the Ugandan economy. On August 4, 1972 Amin issued a decree ordering the expulsion of the 60,000 Asians who were not Ugandan citizens (most of them held British passports). This was later amended to include all 80,000 Asians, but to exempt professionals, such as doctors, lawyers and teachers. Most of the Asians with British passports - around 30,000 - emigrated to Britain. Others went to Canada, Australia, India, the U.S. and Sweden.[15]

After their expulsion, businesses and properties belonging to the Asians were expropriated, most of them handed over to Amin's supporters. The businesses were mismanaged, and industries collapsed from lack of maintenance, proving disastrous for the already declining economy.[11]

International relations

The expulsion of Indian citizens severed relations between India and Uganda. The government of India warned Uganda of dire consequences if no actions were taken to prevent the anti-Indian violence. However, ignored by Amin, India did not take any diplomatic action against Uganda.

In 1972, Amin severed diplomatic ties with Britain and nationalized 85 British owned businesses. He also expelled Israeli military advisors, turning instead to Muammar al-Qaddafi of Libya and the Soviet Union for support.[5]

In 1973, the United States closed its embassy in Kampala, after U.S. Ambassador Thomas Patrick Melady recommended that the United States reduce its presence in Uganda. Melady described Amin's regime as "racist, erratic, brutal, inept, bellicose, irrational, ridiculous, militaristic and above all xenophobic."[16]

In June 1976, Idi Amin allowed an Air France airplane hijacked by two members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine - External Operations (PFLP-EO) and two members of the German "Revolutionary_Cells" (RZ) to land at Entebbe International Airport. At Entebbe, the hijackers were joined by three more. Soon after, 156 hostages were released and flown to safety, while 83 Israeli citizens and/or Jews were held hostage together with 20 others who refused to abandon them. In the subsequent Israeli rescue operation, dubbed "Operation Entebbe," nearly all of the hostages were freed. Three hostages died and ten were wounded; six hijackers, 45 Ugandan soldiers, and one Israeli soldier, Jonathan Netanyahu, were killed. This incident further soured international relations, leading Britain to close its High Commission in Uganda.[17]

Uganda under Amin embarked on a large military build-up, which raised concerns in Kenya. Early in June 1975, Kenyan officials impounded a large convoy of Soviet-made arms en route to Uganda at the port of Mombasa. Tension between Uganda and Kenya reached its climax in February 1976 when Amin announced that he would investigate the possibility that parts of southern Sudan and western and central Kenya, up to within 32 km of Nairobi, were historically a part of colonial Uganda. The Politics of Kenya|Kenyan Government responded with a stern statement that Kenya would not part with "a single inch of territory." Amin finally backed down after the Kenyan army deployed troops and armored personnel carriers along the Kenya-Uganda border.

After Amin's death in August 2003, David Owen said that while he was the British Foreign Secretary (1977–1979), he had suggested that Amin be assassinated, but the proposal was seen as outrageous, and rejected.[18]

Amin's erratic behavior

As the years went on, Amin became increasingly erratic and outspoken. He granted himself a number of grandiose titles, including "King of Scotland" and "Lord of all the Beasts of the Earth and the Fishes of the Sea."[5] Amin styled himself His Excellency, President of Uganda, President President for Life, Field Marshal Al Hadji, Doctor Idi Amin,[19] VC,[20] Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, Lord of All the Beasts of the Earth and Fishes of the Sea, and Conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in General and Uganda in Particular.[21] Some have suggested that Amin suffered from syphilis, which might explain some of his erratic behavior.[22]

Earlier, in 1971, Amin and Zaire's president Mobutu Sese Seko renamed Lake Albert and Lake Edward to Lake Mobutu and Lake Idi Amin Dada respectively.[23] Many foreign journalists considered him a somewhat comical and eccentric figure. In 1977, Time magazine called him a "killer and clown, big-hearted buffoon and strutting martinet."[24]

In 1977, after Britain had broken diplomatic relations with his regime, Amin declared he had beaten the British and conferred on himself the decoration of CBE (Conqueror of the British Empire). Radio Uganda then read out the whole of his new title: "His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal HaDji Doctor Idi Amin Dada, VC, Distinguished Service Order, Military Cross, CBE."[3].

Idi Amin became the subject of many rumors and myths, including a widespread rumor that he was a cannibal. Some of the unsubstantiated myths were spread and popularized by the 1980 film, Rise and Fall of Idi Amin.

Deposition and exile

By 1978, Amin was facing increasing dissent from within Uganda, his circle of close associates having shrunk significantly. After the killings of Archbishop Luwum and ministers Oryema and Oboth Ofumbi in 1977, several of Amin's ministers defected or fled to exile. Later that year, after Amin's Vice President, General Mustafa Adrisi was injured in a suspicious car accident, troops loyal to him mutinied. Amin sent troops against the mutineers, some of whom had fled across the Tanzanian border.[11] Amin then accused Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere of waging war against Uganda, ordered the invasion of Tanzanian territory, and formally annexed a section of the Kagera Region across the boundary.[11][12]

Nyerere mobilized the Tanzania People's Defence Force and counterattacked, joined by several groups of Ugandan exiles who had united as the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA). Amin's army retreated steadily, and despite military help from Libya's Muammar al-Gaddafi, he was forced to flee on April 11, 1979 when Kampala was captured. He fled first to Libya, where sources are divided on whether he remained until December 1979 or early 1980, before finding final asylum in Saudi Arabia. He opened a bank account in Jeddah and resided there, subsisting on a government stipend, on the condition that he indefinitely remain incommunicado. The new Ugandan government chose to keep him exiled, saying that Amin would face war crimes charges if he ever returned. The Saudi motive was to silence him because of the harm they believed he was doing to Islam.[3]

In 1989, Amin, who had always held that Uganda needed him, and who never expressed remorse for the crimes of his regime,[25] attempted to return to Uganda, apparently to lead an armed group organized by Col. Juma Oris. He reached Kinshasa, Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo), before Zairian President Mobutu forced him to return to Saudi Arabia.

Family and associates

Wives

A polygamist, Idi Amin married at least five wives, three of whom he divorced. He married his first wife, Malyamu in 1966, and his second, Kay, in the same year. The following year he married Nora. In 1972 he announced his marriage to Nalongo Madina. On March 26, 1974 he announced on Radio Uganda that he had divorced Malyamu, Nora, and Kay. Malyamu was arrested in Tororo on the Kenyan border in April 1974, accused of smuggling a bolt of fabric into Kenya. She later moved to London. Kay died on August 13, 1974. She is suspected to have died as her lover Doctor Mbalu Mukasa (who himself committed suicide) attempted a surgical abortion. Her body was found dismembered.[26] In July 1975 during the Organisation of African Unity (OAU) summit meeting in Kampala, Amin staged a £2 million wedding to 19-year-old Sarah Kyolaba, a go-go dancer with the Revolutionary Suicide Mechanised Regiment Band, nicknamed "Suicide Sarah." Sarah's boyfriend, whom she was living with before she met Amin, vanished and was never heard of again.[27] By 1993, Amin was living with the last nine of his children and one wife, Mama a Chumaru, the mother of the youngest four of his children. His last known child, daughter Iman, was born in 1992.[28] It was reported that he married a seventh wife a few months before his death in 2003.[29]

Children

Sources differ widely on the number of children Amin fathered, most stating between 30 and 45.[30] A report in The Monitor (Uganda) says he was survived by 45 children,[29] while another by the BBC gives the figure at 54. [31] Taban Amin, Idi Amin's eldest son, was until 2003 the leader of West Nile Bank Front (WBNF), a rebel group opposed to the Government of Yoweri Museveni. In 2005 he was offered amnesty by Museveni, and in 2006 he was appointed as a deputy director general of the Internal Security Organisation.[32] Another of Amin’s sons, Haji Ali Amin, ran for election as chairman (mayor) of Njeru Town council in 2002, but was not elected.[33] In early 2007, the award-winning film The Last King of Scotland, in which Forest Whitaker, who won the Academy Award for Best Actor for his role portraying Idi Amin, prompted one of his sons, Jaffar Amin, to speak out in his father's defense. Jaffar Amin said he was writing a book to counter his father's reputation.[34]

Death

On July 20, 2003, one of Idi Amin's wives, Madina, reported that he was near death, and in a coma at King Faisal Specialist Hospital in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. She pleaded with Ugandan president Yoweri Museveni that he be allowed to return to die in Uganda. Museveni replied that Amin would have to "answer for his sins the moment he was brought back."[35]

Idi Amin died in Saudi Arabia on August 16, 2003, and was buried in Ruwais cemetery in Jeddah.[36]

Legacy

Idi Amin's leadership of Uganda may have begun with popular support as Uganda struggled to realize peace and prosperity as an independent nation after decades of colonial rule. However, the result was far from what anyone hoped for. Most analysts point to Idi Amin's unsuitability to exercise the level of power he achieved. If he was supported, at least initially, by the British authorities it may have been due to a mistaken view that since he had served in the British forces, they could count him as one of themselves.[3] In fact, Amin made it clear from the outset that he wanted to distance himself, and his nation, from the colonial past. Conveniently, however, he blamed Britain for Uganda's economic problems even though Uganda had been independent for nine years when he seized power.

It is true, however, that Britain had left Uganda with almost non-existent political systems and had involved few Africans in governing their own country. Before granting independence, they considered unifying Uganda with Kenya and Tanganyika in a Federacy. Nor did they clarify the position of the traditional King of Buganda in the post-colonial space. Britain, too, made a net profit from its colonial possessions and while she talked about her moral responsibility towards her colonial subjects, she did little to encourage self-determination. She did leave behind educational systems but these taught students how to become European, not to value or to take pride in things African. At one point, Britain had been prepared to hand a large tract of Uganda over to the World Jewish Congress, an offer made in 1906.

Yet many, although not all, of Uganda's problems were caused by Amin himself. Expelling the Asians only exacerbated the economic decline. Unfortunately, and for this the British do shoulder a fair share of blame, Africans did not have the necessary skills to replace the departing Asians. Idi Amin's own impoverished upbringing could not resist the "good life" and the good intent with which he began dissolved in an extravagance his country could ill afford. He saw himself as a leader within what is now the African Union and as a friend of the Palestinians and of oppressed people around the world, hence his virtual co-operation with the PLO hijackers.

Portrayal in media

Film dramatizations

- Victory at Entebbe (1976), a TV film about Operation Entebbe. Julius Harris played Amin.

- Raid on Entebbe (1977), a film depicting the events of Operation Entebbe. Yaphet Kotto played Amin as a charismatic but short-tempered political and military leader.

- In Mivtsa Yonatan (1977; also known as Operation Thunderbolt), an Israeli film about Operation Entebbe, Jamaican-born British actor Mark Heath played Amin, who in this film is first angered by the Palestinian terrorists whom he later comes to support.

- Rise and Fall of Idi Amin (1981), a film recreating Idi Amin's atrocities. Amin is played by Kenyan actor Joseph Olita.

- Mississippi Masala (1991), a film depicting the resettlement of an Indian family after the expulsion of Asians from Uganda by Idi Amin. Joseph Olita again played Amin in a cameo.

- The Last King of Scotland (2006), a film adaptation of Giles Foden's 1998 novel of the same name. For his portrayal of Idi Amin in this film, Forest Whitaker won the Academy Award for Best Actor, a BAFTA, the Screen Actors' Guild Award for Best Actor (Drama), and a Golden Globe

Documentaries

- General Idi Amin Dada: A Self Portrait (1974), directed by French filmmaker Barbet Schroeder.

- Idi Amin: Monster in Disguise (1997), a television documentary directed by Greg Baker.

- The Man Who Ate His Archbishop's Liver? (2004), a television documentary written, produced and directed by Elizabeth C. Jones for Associated-Rediffusion and Channel 4.

- The Man Who Stole Uganda (1971), World In Action.

- Inside Idi Amin's Terror Machine (1979), World In Action.

Notes

- ↑ Chris Elliott, Idi Amin’s son complains about the Guardian’s obituary notice The Guardian, November 30, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Fred Guweddeko, Rejected then taken in by dad; a timeline The Monitor, January 3, 2004. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 Patrick Keatley, Obituary: Idi Ami" The Guardian, August 18, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Jan Palmowski, Dictionary of Contemporary World History: From 1900 to the present day (New York: Oxford University Press, 2003, ISBN 9780198604846).

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 Idi Amin The Scotsman, August 18, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Paul Nantulya, “Exclusion, Identity and Armed Conflict: A Historical Survey of the Politics of Confrontation in Uganda with Specific Reference to the Independence Era,” in Politics of Identity and Exclusion in Africa: From Violent Confrontation to Peaceful Cooperation (Konrad Adenauer Stiftung and Universiteit Van Pretoria, 2001).

- ↑ Richard Reid, Idi Amin's Coup d’État, Uganda 1971 Origins, January 2021. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Idi Amin ousts Uganda president BBC, January 25, 1971. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ John Fairhall, Curfew in Uganda after military coup topples Obote The Guardian, January 26, 1971. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Bryan Appleyard, A wolf in sheep’s clothing The Sunday Times, January 10, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 Military Rule Under Amin Library of Congress. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 An Idi-otic Invasion TIME Magazine, November 13, 1978. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Idi Amin: Obituary The Daily Telegraph, August 17, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Idi Amin: 'Butcher of Uganda' CNN, August 16, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 1972: Asians given 90 days to leave Uganda BBC. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Telegram 1 From the Embassy in Uganda to the Department of State, January 2, 1973 Foreign Relations, 1969-1976, Volume E-6, Documents on Africa, 1973-1976, US Department of State. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ British grandmother missing in Uganda BBC, July 7, 1976. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ UK considered killing Idi Amin BBC, August 16, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ He conferred a Juris Doctor on himself from Makerere University

- ↑ "Victorious Cross" (VC) was a medal made to emulate the British Victoria Cross Obituary: The buffoon tyrant BBC, August 16, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Alistair Boddy-Evans, Biography of Idi Amin, Brutal Dictator of Uganda ThoughtCo., May 13, 2019. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Michael T. Kaufman, Idi Amin, Brutal Ruler of Uganda in the 70s, dies The New York Times, August 15, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Purges and Peace Talks TIME, October 16, 1972. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Amin:The Wild Man of Africa TIME, March 7, 1977. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Riccardo Orizio and Avril Bardoni, Talk of the Devil: Encounters With Seven Dictators (Walker & Company, 2004, ISBN 0802776922).

- ↑ The life and loves of a tyrant Daily Nation, August 20, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Sarah Amin, 1954 - 2015 The Monitor, June 13, 2015. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Giles Foden, Not quite a chip off the old block The Guardian, August 3, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 David Kibirige, Idi Amin is dead The Monitor, August 17, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ According to Henry Kyema, in State of Blood (published in 1977), Idi Amin had 34 children. Some sources say Amin claimed to have fathered 32 children.

- ↑ Amins row over inheritance BBC, August 25, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Tristan Mcconnell, Return of Idi Amin's son casts a shadow over Ugandan election The Daily Telegraph, February 11, 2006. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Amin's son runs for mayor BBC, January 3, 2002. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Idi Amin's son lashes out over 'Last King' USA Today, February 22, 2007. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Idi Amin back in media spotlight BBC, July 25, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

- ↑ Idi Amin buried in Jeddah Al Jazeera, August 16, 2003. Retrieved March 7, 2021.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Allen, John. Idi Amin: History's villains. San Diego, CA: Blackbirch Press, 2004. ISBN 9781567117592

- Avirgan, Tony, and Martha Honey. War in Uganda: The Legacy of Idi Amin. Westport, CT: L. Hill, 1982. ISBN 9780882081373

- Chomsky, Marvin J. (director) Victory at Entebbe (TV film) Warner Bros, 1976 drama based on the Israeli hostage rescue mission

- Foden, Giles. The Last King of Scotland. New York, NY: Knopf, 1998. ISBN 9780375403606 An award winning novel and the basis of the film, The Last King of Scotland, directed by Kevin Macdonald, Beverly Hills, CA: 20th Century Fox Home Entertainment, 2007.

- Kyemba, Henry. A State of Blood. Corgi, 1977. ISBN 978-0552105583

- Gwyn, David. Idi Amin: Death-Light of Africa. Boston, MA: Little, Brown, 1977. ISBN 9780316332309

- Melady, Thomas Patrick, and Margaret Badum Melady. Idi Amin Dada: Hitler in Africa. Kansas City, MO: Sheed Andrews and McMeel, 1977. ISBN 9780836207835

- Orizio, Riccardo, and Avril Bardoni. Talk of the Devil: Encounters with Seven Dictators. New York, NY: Walker, 2003. ISBN 9780802714169

- Palmowski, Jan. Dictionary of Contemporary World History: From 1900 to the present day. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2003. ISBN 9780198604846

External links

All links retrieved November 28, 2024.

- Barron, Brian. The Idi Amin I knew BBC, August 16, 2003.

- O'Kadameri, Billie. Separate fact from fiction in Amin stories The Monitor, September 1, 2003.

- idiamindada.com a website devoted to Idi Amin's legacy created by his son Jaffar Amin.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.