Alien and Sedition Acts

The Alien and Sedition Acts were four laws passed by the United States Congress in 1798 and signed into law by President John Adams, ostensibly designed to protect the United States from citizens of enemy powers during the turmoil following the French Revolution and to stop seditious factions from weakening the government of the new republic. Federalist proponents claimed they were war measures, while the Democratic-Republicans attacked the acts as unconstitutional, an infringement on the rights of the states, and designed primarily to stifle criticism of the administration.

The most controversial of the four statutes was the Sedition Act, which was widely seen as an attempt to curb the vitriolic political abuse directed particularly at the Adams administration. Popular outrage against the laws helped Thomas Jefferson defeat John Adams in the election of 1800 and secure a Republican majority in the Congress.

Jefferson held the acts to be unconstitutional and void and, with James Madison, drafted the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which attempted to nullify the federal laws as a prerogative of states. Upon his election in 1800, Jefferson pardoned and ordered the release of all who had been convicted of violating them. Most of the acts expired or were repealed by 1802, although the Alien Enemies Act remains in effect and has frequently been enforced in wartime.

The Alien and Sedition Acts have been excoriated by historians as flagrant violations of American liberties. Their swift repeal underscored the importance Americans placed upon freedoms lately won and of the capacity of the government in its infancy to protect civil liberties.

Component Acts

There were four separate laws making up what is commonly referred to as the Alien and Sedition Acts:

- The Naturalization Act (official title: An Act to Establish an Uniform Rule of Naturalization) extended the duration of residence required for aliens to become citizens, from five years to fourteen. Enacted June 18, 1798, with no expiration date, it was repealed in 1802.

- The Alien Friends Act (official title: An Act Concerning Aliens) authorized the president to deport any resident alien considered "dangerous to the peace and safety of the United States." Enacted June 25, 1798, with a two year expiration date.

- The Alien Enemies Act (official title: An Act Respecting Alien Enemies) authorized the president to apprehend and deport resident aliens if their home countries were at war with the United States. Enacted July 6, 1798, with no expiration date, it remains in effect today as 50 USC Sections 21-24.

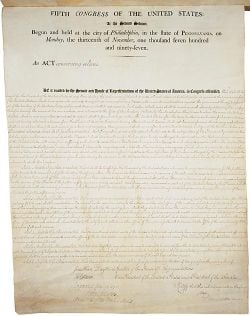

- The Sedition Act (official title: An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes against the United States) made it a crime to publish "false, scandalous, and malicious writing" against the government or its officials. Enacted July 14, 1798, with an expiration date of March 3, 1801.

Background

In the summer of 1798 the young United States was increasingly being drawn into the conflict between Great Britain and France. Some saw France, which championed republican values and supported the new country during the American Revolution, as a natural ally. Following the French Revolution of 1789, many worried that the turmoil and anticlerical violence in France could spread to America's shores. French impressment of American sailors, the botched diplomacy of French Ambassador "Citizen" Genet, and attempts to obtain bribes in exchange for French guarantees to avoid war, known as the XYZ affair, turned popular opinion against France. In an attempt to further isolate pro-French Republicans, the Federalist party in power passed a series of four laws collectively termed the Alien and Sedition Acts.

The first law, the Naturalization Act, in effect restricted recent immigrantsânotably French refugees who sided with the Jefferson Republicansâfrom voting in upcoming elections. The Alien Enemies and Alien Acts also targeted recent French arrivals, many of whom fled the country. These acts were never enforced. The Sedition Act, however, applied not to French immigrants but to American citizens who criticized the president or Congress, and created a storm of protest.

There has been considerable debate over the meaning and interpretation of the Sedition Act. It is clear that American jurisprudence regarding the freedom of speech at some point broke from earlier British law, which held that speech was an act that could be "seditious" regardless of its truth or veracity, and that free speech could be limited based on governmental priorities. For example, the Democratic-Republicans and a number of moderate Federalists successfully added language to the Sedition Act that, by its terms, required "a false, scandalous and malicious writing," pointing to the trial of John Peter Zenger, which established that colonial courts might treat truth as a defense to libel. However, many Federalist judges did not interpret the law consistently with this reading, and there is an ongoing historical debateâhighly relevant in particular to originalist interpretations of the First Amendment and to the question of whether the Sedition Act was unconstitutionalâas to when and the extent to which the break with British precedent occurred.

President Adams never asked for nor encouraged the legislation and never invoked his authority to expel aliens. Nevertheless, his signature on the repressive acts has often overshadowed his more important legacy of keeping the United States out of war during the country's fragile beginnings, despite extraordinary provocations.

Constitutionality

While Jefferson denounced the Sedition Act as a violation of the First Amendment of the United States Constitution, which protected the right of free speech, his main constitutional argument was that the act violated the Tenth Amendment: "The powers not delegated to the United States by the Constitution, nor prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the States respectively, or to the people." In 1798, when the Alien and Sedition Acts were passed, First Amendment rights did not restrict the states, as they now do. Jefferson argued the Federal Government had overstepped its bounds in the Alien and Sedition Acts by attempting to exercise undelegated powers.

In order to address the constitutionality of the measures, Jefferson and James Madison anonymously drafted the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, which called on these states to nullify the federal legislation. The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions argue that the Constitution is a compact, based upon a voluntary union of States that agree to cede some of their authority in order to join the union, but that the states do not, ultimately, surrender their sovereign rights. Therefore, states can determine if the federal government has violated its agreements, including the Constitution, and nullify such violations or even withdraw from the Union. Variations of this theory were also argued at the Hartford Convention at the time of the War of 1812, by the Southern states during the Nullification crisis during the Jackson administration, and just before the American Civil War. Apart from Virginia and Kentucky, the other state legislatures, all of them Federalist, rejected Jefferson's position by resolutions that either supported the acts, or denied that Virginia and Kentucky could nullify them.

Judicial review of the constitutionality of federal legislation was not established until the landmark case of Marbury v. Madison in 1803, so there was effectively no check on federal lawmakers. The Sedition Act was set to expire in 1801, coinciding with the end of the Adams administration. While this prevented its constitutionality from being directly decided by the Supreme Court, subsequent mentions of the Sedition Act in Supreme Court opinions have assumed that it would be found unconstitutional today. For example, in the seminal Free Speech case of New York Times v. Sullivan, the Court declared, "Although the Sedition Act was never tested in this Court, the attack upon its validity has carried the day in the court of history" (376 U.S. 254, 276) (1964).

Elections of 1800

Although the Federalists hoped the acts would stifle the opposition, partisan criticism of the Federalists, and of the acts, grew. As the dangers of war with France abated, popular opposition to the acts emerged as one of the largest election issues.

Although lists of aliens for deportation were prepared, and many aliens fled the country during the debate over the Acts, Adams never signed a deportation order and never actively supported the acts. Still, twenty-five people, primarily prominent newspaper editors but also Congressman Matthew Lyon, were arrested. Of them, eleven were tried (one died while awaiting trial), and ten were convicted of sedition, often in trials before openly partisan Federalist judges. Thought to be an expedient political measure, the Alien and Sedition Acts ultimately backfired against the Federalists. Federalists at all levels were turned out of power and the party soon ceased to exist. Over the following years, Congress repeatedly apologized for, or voted recompense to victims of, the enforcement of the Alien and Sedition Acts. Thomas Jefferson, who won the 1800 election, pardoned all of those that were convicted for crimes under the Alien Enemies Act and the Sedition Act.

Full cites

- An Act to Establish an Uniform Rule of Naturalization (Naturalization Act of 1798), June 181798 ch. 54, 1 Stat. 566

- An Act Concerning Aliens, June 251798 ch. 58, 1 Stat. 570

- An Act Respecting Alien Enemies, July 61798 ch. 66, 1 Stat. 577

- An Act for the Punishment of Certain Crimes against the United States (Sedition Act), July 141798 ch. 74, 1 Stat. 596

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Elkins, Stanley M., and Eric L. McKitrick. The Age of Federalism. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993. ISBN 9780195068900.

- Rehnquist, William H. Grand Inquests: The historic Impeachments of Justice Samuel Chase and President Andrew Johnson. New York: Morrow, 1994. ISBN 9780688051426.

- Rosenfeld, Richard N. American Aurora: A Democratic-Republican Returns: The Suppressed History of Our Nation's Beginnings and the Heroic Newspaper That Tried to Report It. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1997. ISBN 9780312150525.

- Randolph, J. W. The Virginia Report of 1799-1800, Touching the Alien and Sedition Laws; together with the Virginia Resolutions of December 21, 1798, the Debate and Proceedings thereon in the House of Delegates of Virginia, and Several Other Documents Illustrative of the Report and Resolutions. Clark, NJ: Lawbook Exchange, 2004. ISBN 9781584773740.

- Stone, Geoffrey R. Perilous Times: Free Speech in Wartime from The Sedition Act of 1798 to The War on Terrorism. New York: W. W. Norton & Co, 2004. ISBN 9780393058802.

External links

All links retrieved July 20, 2023.

- Alien and Sedition Acts and related resources at the Library of Congress

- An Act Respecting Alien Enemies

- The Alien and Sedition Acts

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.