Difference between revisions of "Peter Frederick Strawson" - New World Encyclopedia

| Line 17: | Line 17: | ||

==Strawson's Work== | ==Strawson's Work== | ||

| − | Strawson first became well known with his article "On Referring" (1950), a criticism of [[Bertrand Russell]]'s [[Theory of Descriptions]] (see also [[Definite description]]s). Russell had analyzed a claim such as "The present King of France is bald" into a conjucntion three statements: (1) There is a king of France. (2) There is just one king of France. (3) | + | Strawson first became well known with his article "On Referring" (1950), a criticism of [[Bertrand Russell]]'s [[Theory of Descriptions]] (see also [[Definite description]]s). Russell had analyzed a claim such as "The present King of France is bald" into a conjucntion of three statements: (1) There is a king of France. (2) There is just one king of France. (3) There is nothing which is king of France and which is not bald. But, Strawson argued, Russell had confused referring to an entity with asserting the existence of that entity. In referring to an entity, Strawson held, the speaker presupposes the existence of the entity, but he does not assert the existence of that entity. Presupposition, according to Strawson, must be distinguished from entailment. So, Strawson held, Russell was mistaken in claiming that the assertion "The present king of France is bald" is false; instead, Strawson claimed, this statement is neither true nor false since its basic presupposition that there is a present king of France is false. |

The mistake in Russell's analysis, according to Strawson, was a confusion between referring and asserting, and that confusion was based on an underlying confusion between a sentence and the statement made in that sentence. Russell—and the logical positivists with him—had held that every sentence is true, false, or meaningless. But Strawson argued that sentences can be meaningful or meaningless without necessarily being true or false. Statements—the assertions made in sentences, but which are distinct from sentences—can be either true or false. So the sentence "The present king of France is bald" is meaningful, but the statement made at the present time using that sentence is neither true nor false because there is no present king of France. | The mistake in Russell's analysis, according to Strawson, was a confusion between referring and asserting, and that confusion was based on an underlying confusion between a sentence and the statement made in that sentence. Russell—and the logical positivists with him—had held that every sentence is true, false, or meaningless. But Strawson argued that sentences can be meaningful or meaningless without necessarily being true or false. Statements—the assertions made in sentences, but which are distinct from sentences—can be either true or false. So the sentence "The present king of France is bald" is meaningful, but the statement made at the present time using that sentence is neither true nor false because there is no present king of France. | ||

| − | In his article "Truth" Strawson criticized the semantic and correspondence theory of truth. He proposed, instead, that "true" does not describe any semantic or other property, but instead we use the word "true" to express agreement, to endorse, to concede, etc. Strawson drew an analogy between this understanding of the word "true" and J.L. Austin's notion of [[performatives]]. Strawson rejected the correspondence theory of truth because, he claimed, the attempt to establish a correspondence between statements and states of affairs beause the notion of "fact" already has what he called the "word-world relationship" built into them. "Facts are what statements (when true) state" he claimed. | + | In his article "Truth" (1949) Strawson criticized the semantic and correspondence theory of truth. He proposed, instead, that "true" does not describe any semantic or other property, but instead we use the word "true" to express agreement, to endorse, to concede, etc. Strawson drew an analogy between this understanding of the word "true" and J.L. Austin's notion of [[performatives]]. Strawson rejected the correspondence theory of truth because, he claimed, the attempt to establish a correspondence between statements and states of affairs beause the notion of "fact" already has what he called the "word-world relationship" built into them. "Facts are what statements (when true) state" he claimed. |

Strawson's first book, ''Introduction to Logical Theory'', dealt with the relationship between ordinary language and formal logic. In the most interesting and important part of this book he held that the formal logical systems of propositional logic and the predicate calculus do not represent well the complex features of the logic of ordinary language. In the last chapter of that book Strawson argued that the attempt to justify induction is necessarily misconceived because there are no higher standards that can be appealed to in justifying induction. Thus, he held, attempting to justify induction is like asking whether a legal system is legal. Just as a legal system provides the standards for what is legal, inductive criteria provide the standards for what counts as induction. | Strawson's first book, ''Introduction to Logical Theory'', dealt with the relationship between ordinary language and formal logic. In the most interesting and important part of this book he held that the formal logical systems of propositional logic and the predicate calculus do not represent well the complex features of the logic of ordinary language. In the last chapter of that book Strawson argued that the attempt to justify induction is necessarily misconceived because there are no higher standards that can be appealed to in justifying induction. Thus, he held, attempting to justify induction is like asking whether a legal system is legal. Just as a legal system provides the standards for what is legal, inductive criteria provide the standards for what counts as induction. | ||

| − | In the 1950s Strawson turned to what he called [[ | + | In the 1950s Strawson turned to what he called [[descriptive metaphysics]]; indeed he was largely responsible for establishing [[metaphysics]] as a worthwhile direction in [[analytic philosophy]]. He distinguished descriptive metaphysics from what he called ''revisionary metaphysics'' in that the descriptive metaphysics he advocated was content to describe the actual structure of our thinking about the world instead of proposing a better structure. It also differed, he claimed, from th usual conceptual analysis in that it attempted to "lay bare the most general features of our conceptual structure." |

| + | |||

| + | Strawson's second book, ''Individuals'', (1959) is probably hs most influential and the one for which he is most remembered. | ||

| + | |||

| + | |||

Revision as of 03:19, 20 August 2007

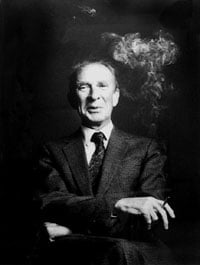

Sir Peter Frederick Strawson (November 23 1919 – 13 February 2006) was an English philosopher. He was the Waynflete Professor of Metaphysical Philosophy at the University of Oxford (Magdalen College) from 1968 to 1987. Before that he was appointed as a college lecturer at University College, Oxford in 1947 and became a tutorial fellow the following year until 1968. On his retirement in 1987, he returned to the college and continued working there until shortly before his death. Strawson was a leading member of the group of philosophers who practiced was known as "Oxford philosophy" or "ordinary language philosophy."

Life

Born in Ealing, West London, Peter Strawson was brought up in Finchley, North London, by his parents, both of whom were teachers. He was educated at Christ's College, Finchley, followed by St John's College, Oxford, where he read Philosophy, Politics, and Economics.

Strawson began teaching at Oxford in 1947, and from 1968 to 1987 was Waynflete Professor of Metaphysics.

Strawson was made a Fellow of the British Academy in 1960, and Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences in 1971. He was president of the Aristotelian Society from 1969 to 1970. He was knighted in 1977, for services to philosophy.

His son, Galen Strawson, is also a philosopher.

Strawson died in the hospital on 13 February 2006 after a short illness.

Strawson's Work

Strawson first became well known with his article "On Referring" (1950), a criticism of Bertrand Russell's Theory of Descriptions (see also Definite descriptions). Russell had analyzed a claim such as "The present King of France is bald" into a conjucntion of three statements: (1) There is a king of France. (2) There is just one king of France. (3) There is nothing which is king of France and which is not bald. But, Strawson argued, Russell had confused referring to an entity with asserting the existence of that entity. In referring to an entity, Strawson held, the speaker presupposes the existence of the entity, but he does not assert the existence of that entity. Presupposition, according to Strawson, must be distinguished from entailment. So, Strawson held, Russell was mistaken in claiming that the assertion "The present king of France is bald" is false; instead, Strawson claimed, this statement is neither true nor false since its basic presupposition that there is a present king of France is false.

The mistake in Russell's analysis, according to Strawson, was a confusion between referring and asserting, and that confusion was based on an underlying confusion between a sentence and the statement made in that sentence. Russell—and the logical positivists with him—had held that every sentence is true, false, or meaningless. But Strawson argued that sentences can be meaningful or meaningless without necessarily being true or false. Statements—the assertions made in sentences, but which are distinct from sentences—can be either true or false. So the sentence "The present king of France is bald" is meaningful, but the statement made at the present time using that sentence is neither true nor false because there is no present king of France.

In his article "Truth" (1949) Strawson criticized the semantic and correspondence theory of truth. He proposed, instead, that "true" does not describe any semantic or other property, but instead we use the word "true" to express agreement, to endorse, to concede, etc. Strawson drew an analogy between this understanding of the word "true" and J.L. Austin's notion of performatives. Strawson rejected the correspondence theory of truth because, he claimed, the attempt to establish a correspondence between statements and states of affairs beause the notion of "fact" already has what he called the "word-world relationship" built into them. "Facts are what statements (when true) state" he claimed.

Strawson's first book, Introduction to Logical Theory, dealt with the relationship between ordinary language and formal logic. In the most interesting and important part of this book he held that the formal logical systems of propositional logic and the predicate calculus do not represent well the complex features of the logic of ordinary language. In the last chapter of that book Strawson argued that the attempt to justify induction is necessarily misconceived because there are no higher standards that can be appealed to in justifying induction. Thus, he held, attempting to justify induction is like asking whether a legal system is legal. Just as a legal system provides the standards for what is legal, inductive criteria provide the standards for what counts as induction.

In the 1950s Strawson turned to what he called descriptive metaphysics; indeed he was largely responsible for establishing metaphysics as a worthwhile direction in analytic philosophy. He distinguished descriptive metaphysics from what he called revisionary metaphysics in that the descriptive metaphysics he advocated was content to describe the actual structure of our thinking about the world instead of proposing a better structure. It also differed, he claimed, from th usual conceptual analysis in that it attempted to "lay bare the most general features of our conceptual structure."

Strawson's second book, Individuals, (1959) is probably hs most influential and the one for which he is most remembered.

In philosophical methodology, Strawson defended a method he called "connective analysis." A connective analysis of a given concept assumes that our concepts form a network, of which the concepts are the nodes. To give a connective analysis of a concept (say, knowledge) is to identify the concepts which are closest to that concept in the network. This kind of analysis has the advantage that a circular analysis (say, analysing knowledge into belief, belief into perception, and perception into knowledge) is not debarred, so long as it is sufficiently encompassing and informative.

Partial bibliography

Books

- Introduction to Logical Theory. London: Methuen, 1952.

- Individuals: An Essay in Descriptive Metaphysics. London: Methuen, 1959.

- The Bounds of Sense: An Essay on Kant's Critique of Pure Reason. London: Methuen, 1966.

- Logico-Linguistic Papers. London: Methuen, 1971

- Freedom and Resentment and other Essays. London: Methuen, 1974

- Subject and Predicate in Logic and Grammar. London: Methuen, 1974

- Skepticism and Naturalism: Some Varieties. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985.

- Analysis and Metaphysics: An Introduction to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1992.

- Entity and Identity. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

Articles

- "Truth" (Analysis, 1949)

- "Truth" (Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society suppl. vol. xxiv, 1950)

- "On Referring" (Mind, 1950)

- "In Defence of a Dogma" with H. P. Grice (Philosophical Review, 1956)

- "Logical Subjects and Physical Objects" (Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, 1957)

- "Singular Terms and Predication" (Journal of Philosophy, 1961)

- "Universals" (Midwest Studies in Philosophy, 1979)

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- The Philosophy of P. F. Strawson, Louis Hahn, ed. (Open Court, 1998)

- Theories of Truth, Richard Kirkham (MIT Press, 1992). (Chapter 10 contains a detailed discussion of Strawson's performative theory of truth.)

- Sir Peter Strawson (1919–2006), Univ Newsletter, Issue 23, page 4, Hilary 2006.

External links

- Freedom and resentment. Full text of his 1962 article.

- Obituary — The Times

- Obituary — The Guardian

- Peter F. Strawson: Analysis and Metaphysics. Roundtable on Strawson in Lima, Peru

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.