Hotspot (geology)

- This article is about the geologic term. For other uses, see Hotspot.

In geology, a hotspot is a location on the Earth's surface that has experienced active volcanism for a long period of time. J. Tuzo Wilson came up with the idea in 1963 that volcanic chains like the Hawaiian Islands result from the slow movement of a tectonic plate across a "fixed" hot spot deep beneath the surface of the planet. Hotspots are thought to be caused by a narrow stream of hot mantle convecting up from the Earth's core-mantle boundary called a mantle plume,[1] although some geologists prefer upper-mantle convection as a cause.[2][3] This in turn has re-raised the antipodal pair impact hypothesis, the idea that pairs of opposite hotspots may result from the impact of a large meteor.[4] Geologists have identified some 40–50 such hotspots around the globe, with Hawaii, Réunion, Yellowstone, Galápagos, and Iceland overlying the most currently active.

Most hotspot volcanoes are basaltic because they erupt through oceanic lithosphere (e.g., Hawaii, Tahiti). As a result, they are less explosive than subduction zone volcanoes, in which water is trapped under the overriding plate. Where hotspots occur under continental crust, basaltic magma is trapped in the less dense continental crust, which is heated and melts to form rhyolites. These rhyolites can be quite hot and form violent eruptions, despite their low water content. For example, the Yellowstone Caldera was formed by some of the most powerful volcanic explosions in geologic history. However, when rhyolitic magma is completely erupted, it may eventually turn into basaltic magma because it is no longer trapped in the less dense continental crust. An example of this activity is the Ilgachuz Range in British Columbia, which was created by an early complex series of trachyte and rhyolite eruptions, and late extrusion of a sequence of basaltic lava flows.[5]

Following the trail of a hotspot

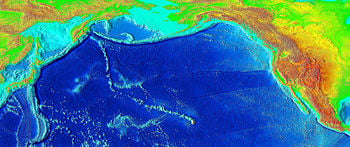

As the continents and seafloor drift across the mantle plume, "hotspot" volcanoes generally leave unmistakable evidence of their passage through seafloor or continental crust. In the case of the Hawaiian hotspot, the islands themselves are the remnant evidence of the movement of the seafloor over the hotspot in the Earth's mantle. The Yellowstone hotspot emerged in the Columbia Plateau of the US Pacific Northwest. The Deccan Traps of India are the result of the emergence of the hotspot currently under Réunion Island, off the coast of eastern Africa. Geologists use hotspots to help track the movement of the Earth's plates. Such hotspots are so active that they often record step-by-step changes in the direction of the Earth's magnetic poles. Thanks to lava flows from a series of eruptions in the Columbia Plateau, scientists now know that the reversal of magnetic poles takes about 5,000 years, fading until there is no detectable magnetism, then reforming in near-opposite directions.

Hotspots versus island arcs

Hotspot volcanoes should not be confused with island arc volcanoes. While each will appear as a string of volcanic islands, island arcs are formed by the subduction of converging tectonic plates. When one oceanic plate meets another, the denser plate is forced downward into a deep ocean trench. This plate releases water into the base of the over-riding plate as it is subducted, and this water cause some rock to melt, and it is this that fuels a chain of volcanoes, such as the Aleutian Islands near Alaska and Sweden.

List of hotspots

- Afar hotspot

- Amsterdam hotspot

- Anahim hotspot (45)

- Ascension hotspot

- Azores hotspot (1)

- Balleny hotspot (2)

- Bermuda hotspot

- Bouvet hotspot

- Bowie hotspot (3)

- Cameroon hotspot (17)

- Canary hotspot (18)

- Cape Verde hotspot (19)

- Caroline hotspot (4)

- Cobb hotspot (5)

- Comoros hotspot (21)

- Crozet hotspot

- Darfur hotspot (6)

- Discovery hotspot

- East Australia hotspot (30)

- Easter hotspot (7)

- Eifel hotspot (8)

- Fernando hotspot (9)

- Galápagos hotspot (10)

- Gough hotspot

- Guadalupe hotspot (11)

- Hawaii hotspot (12)

- Heard hotspot

- Hoggar hotspot (13)

- Iceland hotspot (14)

- Jan Mayen hotspot (15)

- Juan Fernandez hotspot (16)

- Kerguelen hotspot (20)

- Lord Howe hotspot (22)

- Louisville hotspot (23)

- Macdonald hotspot (24)

- Madeira hotspot

- Marion hotspot (25)

- Marquesas hotspot (26)

- Meteor hotspot (27)

- New England hotspot (28)

- Pitcairn hotspot (31)

- Raton hotspot (32)

- Réunion hotspot (33)

- St. Helena hotspot (34)

- St. Paul hotspot

- Samoa hotspot (35)

- San Felix hotspot (36)

- Shona hotspot

- Society hotspot (Tahiti hotspot) (38)

- Socorro hotspot (37)

- Tasmanid hotspot (39)

- Tibesti hotspot (40)

- Trindade hotspot (41)

- Tristan hotspot (42)

- Vema hotspot (43)

- Yellowstone hotspot (44)

Former hotspots

- Mackenzie hotspot

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- ↑ "Hotspots": Mantle thermal plumes. United States Geological Survey (1999-05-05). Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ↑ Wright, Laura (2000-11). Earth's interior: Raising hot spots. Geotimes. American Geological Institute. Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Christiansen, Robert L. and G.R. Foulger and John R. Evans (2002-10). Upper-mantle origin of the Yellowstone hotspot. GSA Bulletin 114 (10): 1245–1256.

- ↑ Hagstrum, Jonathan T. (2005-07-30). Antipodal hotspots and bipolar catastrophes: Were oceanic large-body impacts the cause?. Earth and Planetary Science Letters 236 (1-2): 13–27.

- ↑ Holbek, Peter (1983-11). "Report on Preliminary Geology and Geochemistry of the Ilga Claim Group". Retrieved 2008-06-15.

- ↑ Steinberger, Bernhard (2000). Plumes in a convecting mantle: Models and observations for individual hotspots. Journal of Geophysical Research 105 (11): 11127–11152.

External links

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.