Difference between revisions of "Fukuzawa Yukichi" - New World Encyclopedia

Keisuke Noda (talk | contribs) (import from wiki) |

Rosie Tanabe (talk | contribs) |

||

| (18 intermediate revisions by 9 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

| − | {{ | + | {{Ebapproved}}{{Approved}}{{Images OK}}{{Submitted}}{{Paid}}{{Copyedited}} |

| − | |||

{{Infobox_Biography | {{Infobox_Biography | ||

|subject_name=Yukichi Fukuzawa | |subject_name=Yukichi Fukuzawa | ||

| Line 8: | Line 7: | ||

|date_of_birth=January 10, 1835 | |date_of_birth=January 10, 1835 | ||

|date_of_death=February 3, 1901 | |date_of_death=February 3, 1901 | ||

| − | |place_of_birth= | + | |place_of_birth=Osaka, [[Japan]] |

|place_of_death=[[Japan]] | |place_of_death=[[Japan]] | ||

}} | }} | ||

| + | '''Fukuzawa Yukichi''' 福澤 諭吉 (January 10, 1835 – February 3, 1901) was a Japanese author, educator, translator, entrepreneur, [[politics |political theorist]] and publisher, and was probably the most influential man outside the [[Japan]]ese government during the [[Meiji Restoration]], following the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868. Born into a poor [[samurai]] family, Fukuzawa diligently educated himself, learning first the Dutch and then the [[English language]]. During the period from 1860 until 1867, he took part in three Shogunate missions to [[Europe]] and the [[United States]], and based on these experiences, he introduced Western culture to Japan through his writings, such as "''Seiyo jijo''" ''(Conditions in the West)''. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Firmly believing in the importance of education and the acquisition of knowledge, he led the struggle to introduce Western ideas in order to increase, as he repeatedly wrote, Japanese “strength and independence.” His ideas about government and social institutions made a lasting impression on a rapidly changing Japan. After the Meiji era, he rejected all government appointments and did not receive any court rank or honors, but remained a private citizen. In 1868 he founded [[Keio University]], the first Japanese university to be independent of the government, which produced many business leaders. He is highly respected as one of the founders of modern Japan. He published many works including "''Gakumon no susume" (Encouragement of Learning'') (1872) and "''Bunmeiron no gairyaku" (An Outline of a Theory of Civilization'') (1875). | ||

| + | {{toc}} | ||

| + | Fukuzawa emphasized importing knowledge and ideas as well as technology and material goods from the West, theorizing that with the necessary foundation of knowledge, Japan could develop its own technology. As one of the intellectual leaders of the Meiji Restoration, he urged people to pursue education as a means of achieving “personal independence” and strength. This attitude is still evident in Japan today, where education is taken very seriously. Fukuzawa advocated a strong Japan which could win the respect of the West, not an expansionist Japan. When he died in 1901, he did not see the imperialist path that the Japanese government was later to follow. | ||

| + | |||

| + | ==Life== | ||

| + | === Early life === | ||

| + | Fukuzawa Yukichi was born January 10, 1835 into an impoverished low-ranking [[samurai]] family of the Nakatsu clan in Osaka. Fukuzawa had little hope for advancement; his family was poor following the early death of his father. After his father died, he returned to Nakatsu and became a disciple of Tsuneto Shiroishi. At the age of 14, Fukuzawa entered a school of Dutch studies, or ''Rangaku ''(a Japanese term used to describe Western knowledge and science during the period before the mid-nineteenth century, when the Dutch were the only Westerners in Japan). In 1853, shortly after Commodore [[Matthew C. Perry]]'s arrival in Japan, Fukuzawa's brother, the family patriarch, asked Fukuzawa to travel to Nagasaki, where the Dutch colony at Dejima was located. Fukuzawa was instructed to learn the Dutch language in order to study European cannon designs and gunnery techniques. | ||

| + | |||

| + | Fukuzawa did travel to Nagasaki, but his stay was brief because he quickly began to do much better in his studies than his host in Nagasaki, Okudairi Iki. The jealous Okudairi plotted to get Fukuzawa to return home by writing a letter saying that Fukuzawa's mother was ill. Fukuzawa recognized the letter as a fake and, knowing that he would not be able to continue his studies in his home town, made plans to travel to Edo (Tokyo) and attend a school there. Upon his return to Osaka, however, his brother persuaded him to stay and enroll at the Tekijuku school run by physician and ''rangaku'' scholar Ogata Koan. Fukuzawa studied at Tekijuku for three years, and became fully proficient in the Dutch language. In 1858, he was appointed official Dutch teacher of his family's domain, Nakatsu, and was sent to Edo to teach the family's vassals there. | ||

| + | |||

| + | The following year, Japan opened three of its ports to American and European ships, and Fukuzawa, intrigued with Western civilization, traveled to Kanagawa to see them. When he arrived, he discovered that virtually all of the European merchants there were speaking [[English language|English]] rather than Dutch. He began to study English, but at that time, English-Japanese interpreters were rare and dictionaries nonexistent, so his studies progressed slowly. | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Image:1860Kanrinmaru delegation.jpg|thumb|right|330px|'''Fukuzawa Yukichi''' was a member of the first ever Japanese delegation to the United States, in 1860 (Washington shipyard).]] | ||

| + | |||

| + | ===Shogunate missions to the West=== | ||

| + | The Tokugawa ''bakufu'' (government) decided to send envoys of the Shogun to the United States, and Fukuzawa volunteered his services to Admiral Kimura Yoshitake. Kimura's ship, the Japanese warship ''Kanrin Maru'' arrived in San Francisco, California in 1860. The delegation stayed in the city for a month, during which time Fukuzawa had himself photographed with an American girl (one of the most famous photographs in Japanese history), and also found a ''Webster's Dictionary,'' from which he began to seriously study the English language. | ||

| + | |||

| + | On his return to Japan in 1860, Fukuzawa became an official translator for the ''bakufu.'' He soon produced his first publication, an English-Japanese dictionary which he called "''Kaei Tsūgo''" (translated from “[[Chinese]]-English dictionary”); the first of a series of books. In 1862, he visited [[Europe]], as one of the two English translators in a delegation of 40 representatives sent by the Tokugawa ''bakufu.'' Negotiations were carried out in [[France]], [[England]], [[Netherlands|Holland]], [[Prussia]], and finally, [[Russia]]. The delegation spent almost an entire year in Europe. In 1867, Fukuzawa returned to America, this time visiting Washington, D.C. and [[New York City]] as part of a team of negotiators. | ||

| − | + | Fukuzawa compiled the information collected during these travels in his famous work ''Seiyo Jijo'' ("''Conditions in The West''"), which he published in ten volumes in 1867, 1868 and 1870. The books, which described Western political, economic and cultural institutions in clear and simple terms that were easy to understand, became immediate best-sellers, and Fukuzawa was soon regarded as the foremost expert on Western culture. He decided that his mission in life was to educate his countrymen in new ways of thinking, which in turn, would strengthen Japan and enable it to resist the threat of European [[imperialism]]. | |

| − | + | ===Introduction of Western Culture to Japan=== | |

| − | + | Before the [[Meiji Restoration]] in 1868, groups of xenophobic [[samurai]] tried to forcefully eject Americans and Europeans, and the Japanese who befriended them, by violence and murder. Many attempts were made on Fukuzawa’s life, and one of his colleagues was murdered. After the Restoration, when the Japanese government began to actively seek information about the West, Fukuzawa was often offered government posts, but he consistently declined, insisting that Japan needed to develop an independent intellectual community, and he remained a private citizen all of his life. | |

| − | |||

| − | + | Fukuzawa wrote more than one hundred books advocating parliamentary government, popular education, language reform, women's rights, and a host of other causes. He was an avid supporter of education and in 1868 founded one of Japan's most prestigious universities, ''Keio-gijuku,'' now known as Keio University. It was the first great Japanese university to be independent of the government, and produced many business leaders. Fukuzawa believed in creating a firm intellectual foundation through education and study. | |

| − | + | In 1882, after being prompted by [[Inoue Kaoru]], [[Okuma Shigenobu]], and [[Ito Hirobumi]] to establish a strong influence among the people through publishing, he founded ''Jiji shimpo'' (“''Current Events''”). For years it was one of Japan's most influential newspapers, and a training ground for many liberal politicians and journalists. ''Jiji Shimpo,'' which received wide circulation, encouraged acceptance of a national assembly as the form for the new government, and urged the people to enlighten themselves and to adopt a moderate political attitude towards the changes that were being engineered within the social and political structures of Japan. | |

| − | + | == Thought and Works == | |

| − | |||

| − | Fukuzawa | + | Fukuzawa's writings were possibly his greatest contribution to the Meiji period. Between 1872 and 1876, he published 17 volumes of ''Gakumon no Susume'' ("''An Encouragement of Learning"'' or more literally "''of Studying''"). Fukuzawa outlined the importance of understanding the principle of equality of opportunity, and emphasized that study was the key to greatness. Fukuzawa also advocated his most lasting principle, "national independence through personal independence." An individual who is personally independent does not have to depend on the strength of another. With such a self-determining social morality, Fukuzawa hoped to instill in the people of Japan a sense of their individual personal strength, and through that personal strength, build a nation to rival all others. He understood that Western society had become a powerful influence over other countries because Western nations fostered [[education]], [[individualism]] (independence), competition and the exchange of ideas. |

| − | + | ===Theory of civilization=== | |

| + | Among the many influential essays and critical works which Fukuzawa published, one of the most enduring is "''Bunmeiron no Gairyaku" ("An Outline of a Theory of Civilization''"), published in 1875, detailing his theory of civilization. According to Fukuzawa, civilization was relative to time and circumstance, as well as relative to other contemporary civilizations. He gave the example that, at that time, [[China]] was relatively civilized in comparison to some of the [[Africa]]n colonies, and European nations were the most civilized of all. Many of Fukuzawa's views were shared by colleagues in the Meirokusha intellectual society, and were published in his contributions to ''Meiroku Zasshi'' ''(Meiji Six Magazine)'', a scholarly journal he helped publish. In his books and journals, he often spoke about the word "civilization" and its meaning. He advocated moving toward "civilization," which meant basic material well-being as well as spiritual well-being, by elevating human life to a "higher plane." Because material and spiritual well-being corresponded to knowledge and virtue, the "move toward civilization" was the advancement and pursuit of knowledge and virtue themselves. | ||

| − | + | Fukuzawa proposed that people could find the answer to the problems of their lives and understand their present situations by examining "civilization." He also maintained that the difference between the weak and the powerful, and large and small, was just a matter of difference in knowledge and education. [[Japan]], he said, should not be just importing new guns and materials from foreign countries, but importing knowledge; if a proper basis of knowledge and education were established, material necessities would take care of themselves. Fukuzawa also talked of the Japanese concept of being [[pragmatism|pragmatic]] ''(jitsugaku)'' and building things that were basic and useful to other people. | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | ===''Argument for leaving Asia''=== | |

| + | One of his most widely read article in Japan at the time was ''Datsu-A Ron,'' translated as ''"Argument for Leaving Asia,''" published in 1885. The article first declared that the "wind of Westernization" was blowing through the east, and Asian countries would either adopt the movement to "taste the fruit of civilization," or be left without a choice as to their own destiny. Fukuzawa maintained that in order to develop personal and national self-determination, one must sail on the aforementioned “winds of civilization.” He described the conservative government of the Tokugawa Shogunate as an impediment on the road to civilization; only when this government was overthrown could civilization be realized in Japan. The key to getting rid of the old, and gaining from the new was, "leaving Asia." During the [[Meiji Restoration]], Japan was seen as spiritually "leaving Asia," although its two neighbors, [[China]] and [[Korea]], did not appear to be embracing such reformation. Unless there were pioneers to reform these countries, they would be conquered and divided by external forces, as evidenced by the unequal treaties and threats of force against Asian counties by the [[United States]] and other Western powers. | ||

| − | + | <blockquote>In my view, these two countries [China and Korea] cannot survive as independent nations with the onslaught of Western civilization to the East...It is not different from the case of the righteous man living in a neighborhood of a town known for foolishness, lawlessness, atrocity, and heartlessness. His action is so rare that it is always buried under the ugliness of his neighbors' activities… The spread of civilization is like the measles… Those [who] are intimate with bad friends are also regarded bad, therefore we should deny those bad Asian friends from our hearts. (Fukuzawa, Yukichi, ''Datsu-A Ron,'' 1885)</blockquote> | |

==Criticism== | ==Criticism== | ||

| − | Fukuzawa was later criticized as a supporter of Japanese [[imperialism]] because of his essay " | + | Fukuzawa was later criticized as a supporter of Japanese [[imperialism]] because of his essay "''Datsu-A Ron''" ("''Leaving Asia,''" 1885), as well as for his support of the [[Japan|First Sino-Japanese War]] (1894-1895). |

| − | His enthusiastic support of the First Sino-Japanese War had much to do with his opinions about modernization. | + | His enthusiastic support of the First Sino-Japanese War had much to do with his opinions about modernization. Like many of his peers in the government, Fukuzawa ultimately believed the modernization of Asia could ultimately only be achieved by force. He believed that [[China]] suffered from archaic and unchanging principles and would be unable to change under its own power. At the time of the war, foot-binding was still the practice in China; opium was being sold on street; and political institutions were corrupt and unable to fend off foreign incursions. China was selling national interests such as railroads and imposing taxation to pay foreign debts. Japan suffered a similar humiliation of having to endure unequal treaties with the Western powers. Fukuzawa hoped a display of military prowess would sway public opinion in the West towards treaty revision, and help Japan to avoid the fate of China. In his hopes for a strong Japan, Fukuzawa saw the Asian countries around Japan as both a danger and an opportunity. |

| − | |||

| − | |||

== Legacy == | == Legacy == | ||

| − | + | In addition to his many original books and articles, Fukuzawa translated many books and journals from foreign languages to Japanese, on a wide variety of subjects such as [[chemistry]], the [[arts]], the [[military]], and [[sociology]]. | |

| − | + | Fukuzawa's ideas about individual strength and his knowledge of Western political theory, as presented in his writings, were instrumental in motivating the Japanese people to embrace change. He may well have been one of the most influential personalities in the modernization of Japan and one of Japan’s most [[progressivism|progressive]] thinkers. He is regarded as one of the leaders of the Meiji Enlightenment movement. By the time of his death, Fukuzawa was revered as one of the founders of modern Japan. All of his works were written during a critical juncture in the history of Japanese society, when the Japanese people felt uncertainty about their future after the signing of the Unequal Treaties, and recognized the weakness of the Togukawa Shogunate and its inability to repel American and European influence. Fukuzawa helped the Japanese people to understand their situation, leave behind their bitterness over American and European forced treaties and "imperialism," and move forward. | |

| − | Fukuzawa's ideas about individual strength and his knowledge of | ||

| − | Fukuzawa appears on the current 10,000-[[Japanese yen|yen]] banknote and has been compared to [[Benjamin Franklin]] in the [[United States]], | + | Fukuzawa appears on the current 10,000-[[Japanese yen|yen]] banknote and has been compared to [[Benjamin Franklin]] in the [[United States]], who appears on the similarly-valued U.S. one-hundred-dollar bill. Although all other personages appearing on Japanese banknotes changed during a recent redesign, Fukuzawa remained on the 10,000-yen note. |

| − | Yukichi Fukuzawa's former residence in the city of | + | Yukichi Fukuzawa's former residence in the city of Nakatsu, in Ōita Prefecture, is a Nationally Designated Cultural Asset. The house and the Yukichi Fukuzawa Memorial Hall are the major tourist attractions of this city. |

| − | == | + | == References == |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | + | *Blacker, Carmen. 1964. ''The Japanese enlightenment; a study of the writings of Fukuzawa Yukichi.'' Cambridge: University Press. | |

| − | * | + | *Fukuzawa, Yukichi, and Eiichi Kiyooka. 1992. ''The autobiography of Fukuzawa Yukichi.'' The Library of Japan. Lanham: Madison Books. ISBN 0819182958 |

| − | + | *Hopper, Helen M. 2004. ''Fukuzawa Yukichi: from samurai to capitalist.'' Library of world biography. New York: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0321078020 | |

| − | + | *Tipton, Elise K. 2002. ''Modern Japan: a social and political history.'' London: Routledge. ISBN 0415185378 | |

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

| − | |||

{{credit|113529325}} | {{credit|113529325}} | ||

| + | |||

| + | [[Category:History]] | ||

Latest revision as of 07:16, 15 April 2024

| Yukichi Fukuzawa |

|---|

| Born |

| January 10, 1835 Osaka, Japan |

| Died |

| February 3, 1901 Japan |

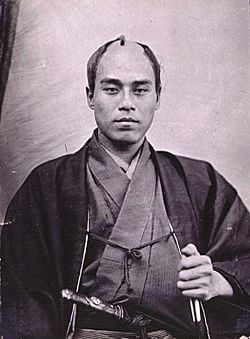

Fukuzawa Yukichi 福澤 諭吉 (January 10, 1835 – February 3, 1901) was a Japanese author, educator, translator, entrepreneur, political theorist and publisher, and was probably the most influential man outside the Japanese government during the Meiji Restoration, following the overthrow of the Tokugawa shogunate in 1868. Born into a poor samurai family, Fukuzawa diligently educated himself, learning first the Dutch and then the English language. During the period from 1860 until 1867, he took part in three Shogunate missions to Europe and the United States, and based on these experiences, he introduced Western culture to Japan through his writings, such as "Seiyo jijo" (Conditions in the West).

Firmly believing in the importance of education and the acquisition of knowledge, he led the struggle to introduce Western ideas in order to increase, as he repeatedly wrote, Japanese “strength and independence.” His ideas about government and social institutions made a lasting impression on a rapidly changing Japan. After the Meiji era, he rejected all government appointments and did not receive any court rank or honors, but remained a private citizen. In 1868 he founded Keio University, the first Japanese university to be independent of the government, which produced many business leaders. He is highly respected as one of the founders of modern Japan. He published many works including "Gakumon no susume" (Encouragement of Learning) (1872) and "Bunmeiron no gairyaku" (An Outline of a Theory of Civilization) (1875).

Fukuzawa emphasized importing knowledge and ideas as well as technology and material goods from the West, theorizing that with the necessary foundation of knowledge, Japan could develop its own technology. As one of the intellectual leaders of the Meiji Restoration, he urged people to pursue education as a means of achieving “personal independence” and strength. This attitude is still evident in Japan today, where education is taken very seriously. Fukuzawa advocated a strong Japan which could win the respect of the West, not an expansionist Japan. When he died in 1901, he did not see the imperialist path that the Japanese government was later to follow.

Life

Early life

Fukuzawa Yukichi was born January 10, 1835 into an impoverished low-ranking samurai family of the Nakatsu clan in Osaka. Fukuzawa had little hope for advancement; his family was poor following the early death of his father. After his father died, he returned to Nakatsu and became a disciple of Tsuneto Shiroishi. At the age of 14, Fukuzawa entered a school of Dutch studies, or Rangaku (a Japanese term used to describe Western knowledge and science during the period before the mid-nineteenth century, when the Dutch were the only Westerners in Japan). In 1853, shortly after Commodore Matthew C. Perry's arrival in Japan, Fukuzawa's brother, the family patriarch, asked Fukuzawa to travel to Nagasaki, where the Dutch colony at Dejima was located. Fukuzawa was instructed to learn the Dutch language in order to study European cannon designs and gunnery techniques.

Fukuzawa did travel to Nagasaki, but his stay was brief because he quickly began to do much better in his studies than his host in Nagasaki, Okudairi Iki. The jealous Okudairi plotted to get Fukuzawa to return home by writing a letter saying that Fukuzawa's mother was ill. Fukuzawa recognized the letter as a fake and, knowing that he would not be able to continue his studies in his home town, made plans to travel to Edo (Tokyo) and attend a school there. Upon his return to Osaka, however, his brother persuaded him to stay and enroll at the Tekijuku school run by physician and rangaku scholar Ogata Koan. Fukuzawa studied at Tekijuku for three years, and became fully proficient in the Dutch language. In 1858, he was appointed official Dutch teacher of his family's domain, Nakatsu, and was sent to Edo to teach the family's vassals there.

The following year, Japan opened three of its ports to American and European ships, and Fukuzawa, intrigued with Western civilization, traveled to Kanagawa to see them. When he arrived, he discovered that virtually all of the European merchants there were speaking English rather than Dutch. He began to study English, but at that time, English-Japanese interpreters were rare and dictionaries nonexistent, so his studies progressed slowly.

Shogunate missions to the West

The Tokugawa bakufu (government) decided to send envoys of the Shogun to the United States, and Fukuzawa volunteered his services to Admiral Kimura Yoshitake. Kimura's ship, the Japanese warship Kanrin Maru arrived in San Francisco, California in 1860. The delegation stayed in the city for a month, during which time Fukuzawa had himself photographed with an American girl (one of the most famous photographs in Japanese history), and also found a Webster's Dictionary, from which he began to seriously study the English language.

On his return to Japan in 1860, Fukuzawa became an official translator for the bakufu. He soon produced his first publication, an English-Japanese dictionary which he called "Kaei Tsūgo" (translated from “Chinese-English dictionary”); the first of a series of books. In 1862, he visited Europe, as one of the two English translators in a delegation of 40 representatives sent by the Tokugawa bakufu. Negotiations were carried out in France, England, Holland, Prussia, and finally, Russia. The delegation spent almost an entire year in Europe. In 1867, Fukuzawa returned to America, this time visiting Washington, D.C. and New York City as part of a team of negotiators.

Fukuzawa compiled the information collected during these travels in his famous work Seiyo Jijo ("Conditions in The West"), which he published in ten volumes in 1867, 1868 and 1870. The books, which described Western political, economic and cultural institutions in clear and simple terms that were easy to understand, became immediate best-sellers, and Fukuzawa was soon regarded as the foremost expert on Western culture. He decided that his mission in life was to educate his countrymen in new ways of thinking, which in turn, would strengthen Japan and enable it to resist the threat of European imperialism.

Introduction of Western Culture to Japan

Before the Meiji Restoration in 1868, groups of xenophobic samurai tried to forcefully eject Americans and Europeans, and the Japanese who befriended them, by violence and murder. Many attempts were made on Fukuzawa’s life, and one of his colleagues was murdered. After the Restoration, when the Japanese government began to actively seek information about the West, Fukuzawa was often offered government posts, but he consistently declined, insisting that Japan needed to develop an independent intellectual community, and he remained a private citizen all of his life.

Fukuzawa wrote more than one hundred books advocating parliamentary government, popular education, language reform, women's rights, and a host of other causes. He was an avid supporter of education and in 1868 founded one of Japan's most prestigious universities, Keio-gijuku, now known as Keio University. It was the first great Japanese university to be independent of the government, and produced many business leaders. Fukuzawa believed in creating a firm intellectual foundation through education and study.

In 1882, after being prompted by Inoue Kaoru, Okuma Shigenobu, and Ito Hirobumi to establish a strong influence among the people through publishing, he founded Jiji shimpo (“Current Events”). For years it was one of Japan's most influential newspapers, and a training ground for many liberal politicians and journalists. Jiji Shimpo, which received wide circulation, encouraged acceptance of a national assembly as the form for the new government, and urged the people to enlighten themselves and to adopt a moderate political attitude towards the changes that were being engineered within the social and political structures of Japan.

Thought and Works

Fukuzawa's writings were possibly his greatest contribution to the Meiji period. Between 1872 and 1876, he published 17 volumes of Gakumon no Susume ("An Encouragement of Learning" or more literally "of Studying"). Fukuzawa outlined the importance of understanding the principle of equality of opportunity, and emphasized that study was the key to greatness. Fukuzawa also advocated his most lasting principle, "national independence through personal independence." An individual who is personally independent does not have to depend on the strength of another. With such a self-determining social morality, Fukuzawa hoped to instill in the people of Japan a sense of their individual personal strength, and through that personal strength, build a nation to rival all others. He understood that Western society had become a powerful influence over other countries because Western nations fostered education, individualism (independence), competition and the exchange of ideas.

Theory of civilization

Among the many influential essays and critical works which Fukuzawa published, one of the most enduring is "Bunmeiron no Gairyaku" ("An Outline of a Theory of Civilization"), published in 1875, detailing his theory of civilization. According to Fukuzawa, civilization was relative to time and circumstance, as well as relative to other contemporary civilizations. He gave the example that, at that time, China was relatively civilized in comparison to some of the African colonies, and European nations were the most civilized of all. Many of Fukuzawa's views were shared by colleagues in the Meirokusha intellectual society, and were published in his contributions to Meiroku Zasshi (Meiji Six Magazine), a scholarly journal he helped publish. In his books and journals, he often spoke about the word "civilization" and its meaning. He advocated moving toward "civilization," which meant basic material well-being as well as spiritual well-being, by elevating human life to a "higher plane." Because material and spiritual well-being corresponded to knowledge and virtue, the "move toward civilization" was the advancement and pursuit of knowledge and virtue themselves.

Fukuzawa proposed that people could find the answer to the problems of their lives and understand their present situations by examining "civilization." He also maintained that the difference between the weak and the powerful, and large and small, was just a matter of difference in knowledge and education. Japan, he said, should not be just importing new guns and materials from foreign countries, but importing knowledge; if a proper basis of knowledge and education were established, material necessities would take care of themselves. Fukuzawa also talked of the Japanese concept of being pragmatic (jitsugaku) and building things that were basic and useful to other people.

Argument for leaving Asia

One of his most widely read article in Japan at the time was Datsu-A Ron, translated as "Argument for Leaving Asia," published in 1885. The article first declared that the "wind of Westernization" was blowing through the east, and Asian countries would either adopt the movement to "taste the fruit of civilization," or be left without a choice as to their own destiny. Fukuzawa maintained that in order to develop personal and national self-determination, one must sail on the aforementioned “winds of civilization.” He described the conservative government of the Tokugawa Shogunate as an impediment on the road to civilization; only when this government was overthrown could civilization be realized in Japan. The key to getting rid of the old, and gaining from the new was, "leaving Asia." During the Meiji Restoration, Japan was seen as spiritually "leaving Asia," although its two neighbors, China and Korea, did not appear to be embracing such reformation. Unless there were pioneers to reform these countries, they would be conquered and divided by external forces, as evidenced by the unequal treaties and threats of force against Asian counties by the United States and other Western powers.

In my view, these two countries [China and Korea] cannot survive as independent nations with the onslaught of Western civilization to the East...It is not different from the case of the righteous man living in a neighborhood of a town known for foolishness, lawlessness, atrocity, and heartlessness. His action is so rare that it is always buried under the ugliness of his neighbors' activities… The spread of civilization is like the measles… Those [who] are intimate with bad friends are also regarded bad, therefore we should deny those bad Asian friends from our hearts. (Fukuzawa, Yukichi, Datsu-A Ron, 1885)

Criticism

Fukuzawa was later criticized as a supporter of Japanese imperialism because of his essay "Datsu-A Ron" ("Leaving Asia," 1885), as well as for his support of the First Sino-Japanese War (1894-1895).

His enthusiastic support of the First Sino-Japanese War had much to do with his opinions about modernization. Like many of his peers in the government, Fukuzawa ultimately believed the modernization of Asia could ultimately only be achieved by force. He believed that China suffered from archaic and unchanging principles and would be unable to change under its own power. At the time of the war, foot-binding was still the practice in China; opium was being sold on street; and political institutions were corrupt and unable to fend off foreign incursions. China was selling national interests such as railroads and imposing taxation to pay foreign debts. Japan suffered a similar humiliation of having to endure unequal treaties with the Western powers. Fukuzawa hoped a display of military prowess would sway public opinion in the West towards treaty revision, and help Japan to avoid the fate of China. In his hopes for a strong Japan, Fukuzawa saw the Asian countries around Japan as both a danger and an opportunity.

Legacy

In addition to his many original books and articles, Fukuzawa translated many books and journals from foreign languages to Japanese, on a wide variety of subjects such as chemistry, the arts, the military, and sociology.

Fukuzawa's ideas about individual strength and his knowledge of Western political theory, as presented in his writings, were instrumental in motivating the Japanese people to embrace change. He may well have been one of the most influential personalities in the modernization of Japan and one of Japan’s most progressive thinkers. He is regarded as one of the leaders of the Meiji Enlightenment movement. By the time of his death, Fukuzawa was revered as one of the founders of modern Japan. All of his works were written during a critical juncture in the history of Japanese society, when the Japanese people felt uncertainty about their future after the signing of the Unequal Treaties, and recognized the weakness of the Togukawa Shogunate and its inability to repel American and European influence. Fukuzawa helped the Japanese people to understand their situation, leave behind their bitterness over American and European forced treaties and "imperialism," and move forward.

Fukuzawa appears on the current 10,000-yen banknote and has been compared to Benjamin Franklin in the United States, who appears on the similarly-valued U.S. one-hundred-dollar bill. Although all other personages appearing on Japanese banknotes changed during a recent redesign, Fukuzawa remained on the 10,000-yen note.

Yukichi Fukuzawa's former residence in the city of Nakatsu, in Ōita Prefecture, is a Nationally Designated Cultural Asset. The house and the Yukichi Fukuzawa Memorial Hall are the major tourist attractions of this city.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Blacker, Carmen. 1964. The Japanese enlightenment; a study of the writings of Fukuzawa Yukichi. Cambridge: University Press.

- Fukuzawa, Yukichi, and Eiichi Kiyooka. 1992. The autobiography of Fukuzawa Yukichi. The Library of Japan. Lanham: Madison Books. ISBN 0819182958

- Hopper, Helen M. 2004. Fukuzawa Yukichi: from samurai to capitalist. Library of world biography. New York: Pearson/Longman. ISBN 0321078020

- Tipton, Elise K. 2002. Modern Japan: a social and political history. London: Routledge. ISBN 0415185378

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.