Washington's Delaware crossing

The Delaware Crossing was declared to be the moment of George Washingtonâs brightest laurels by Charles Cornwallis. It was also a great and desperate gamble that changed the course of North American history and turned the tide against the British in the American Revolutionary War.

Introduction

General Washington was faced with overwhelming military odds and the certain destruction of the American colonies' quest for independence. Twelve thousand British troops were slowed only by weather in their unopposed advance across New Jersey. Facing separate army groups under the seasoned commands of British Generals Howe, and Cornwallis, Washington knew his options were limited. A keen student of history and a former officer of the Virginia Regiment in the British Army, George Washington was well aware this enemy had not lost a war in centuries.

His remaining 2,400 men on the western bank of the Delaware River huddled nine miles north of the Hessian encampment at Trenton had few choices. They were surrounded by unfriendly locals who believed the revolution all but lost, and tradesmen unwilling to extend credit. They were cold and hungry and for many their enlistments were up in less than one week. In the face of certain and permanent defeat, Washington chose Christmas Day, 1776, to sling his stone at the goliath's forehead.

His goal was simple. Capture the stores of food, clothing, blankets, and munitions from the regiments of Hessian mercenaries stationed in Trenton and drive them out of the city. If successful, Washington would then be strategically placed to prevent the British from sweeping him aside and overrunning Philadelphia and decisively disrupting the American rebellion.

The Hessians waited also. Quartered warmly in the city of Trenton, they paused in anticipation of joining forces with the approaching British. The columns led by Generals Howe, Gage, and Cornwallis coming westward across New Jersey planned on arriving in time for the Delaware River to freeze over. Once that convergence in time occurred, the German mercenaries would spearhead the mortal blow to the colonists' insurrection.

George Washington

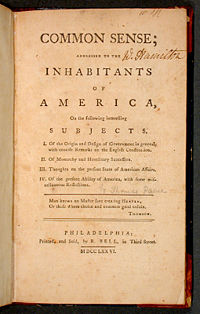

George Washington was known in his time as a man of great personal reserve and absolute conviction. John Adams, then head of the Massachusetts Legislature, suggested Washington's appointment to command the Continental Army in June of 1775 citing his "skill as an officerâŚgreat talents and universal character." Washington assumed command on July 3, 1775. However, he did not support colonial independence until 1776 and only then convinced by the writings of Thomas Paine in the pamphlet âCommon Senseââ first published on January 10, 1776. Barely three months later, on March 17, 1776, Washington commanded the American forces that drove the British from Boston.

He stationed his artillery on Dorchester Heights overlooking Boston under the command of Henry Knox a former Boston bookseller. The looming threat of a cannonade and subsequent siege action caused the British commander, General William Howe, who had recently been sent to replace General Thomas Gage, to retreat with his army to Halifax, Canada. After successfully driving the British from Boston, Washington then moved his army to New York City in anticipation of a British offensive there. Washington lost the Battle of Long Island on August 22 but managed an organized retreat, saving most of his forces. However, several other battles in the area sent Washington's army scrambling across New Jersey, leaving the future of the revolution in doubt.

On the night of December 25, 1776, Washington planned to lead the American forces back across the Delaware River to attack Hessian forces in the city of Trenton, New Jersey. The Hessians were anticipating an attack, but had little respect for what they considered an ill-trained army of farmers. Washington hoped, if successful, that the attack would build morale among the pro-independence colonists, rekindle the spirit that had formed the insurrection, restore the trust of the bankers financing his army, and bring safety at least for that winter to the Continental Congress and the colonial government in and around Philadelphia.

Preparation

In preparation for the Battle of Trenton, George Washington split his company of three thousand men, already outnumbered almost four to one, during the last weeks of December 1776. Through historical records and his own multitude of correspondence, it is known that Washingtonâs success at Trenton did not come without a price.

Under the command of Colonel John Cadwallader, Washington sent 600 soldiers to take up position in Bristol, Pennsylvania a few miles north of Philadelphia on the Delaware River. The intent was to have this force cross the Delaware and attack Trenton from the south. Inclement weather and river ice prevented Cadwallader from crossing his cannon and joining Washingtonâs men at the appointed 5:00 a.m. rendezvous in Trenton.

Further south in New Jersey, Colonel Samuel Griffin surprised British forces. Griffin had moved across the Delaware with a contingent of soldiers from Philadelphia and gathered some New Jersey Militia and faced off against the British troops at Mount Holly, New Jersey. His presence stirred up the British to a watchfulness that nearly defeated Washington's attack on Trenton. He had done this contrary to orders from Washington, who had in fact preferred Griffin and his company go to Bristol and join with Cadwallader.[1]

The Plan of Attack

The plan, according to Washingtonâs correspondence with Major General Joseph Spencer of December 22, was to have Colonel Cadwallader and Colonel Griffinâs men cross the Delaware together with 1,200 soldiers and militia on December 23 and join the attack on Trenton. [2]

Directly across the Delaware from Trenton in Morrisville, Pennsylvania, General James Ewing with less than 150 men, so decimated were the ranks of the Continental Army, was ordered to cross the Delaware and join Washington. Here too weather and river ice conspired to keep Washingtonâs force fragmented and his plans for victory in doubt.

Nine miles to the north at McKonkeyâs Ferry, on the afternoon of December 25, Washingtonâs men began their river crossing. The plan was to cross two divisions, 2,400 soldiers and cannon using ferry boats. Knowing that Griffinâs actions had alerted the British and that Cadwallader could not meet him and that Ewingâs force was too small, Washington continued. His belief and faith is well-documented. As commander of the American forces, he knew with prayerful purpose and divine inspiration, his army held the only hope to save the war of independence for the American cause. His correspondence to family (Lund Washington)[3] and his friend and financier (Robert Morris)[4] shows clearly he knew that an attack of overwhelming force was bearing down on Philadelphia as soon as the Delaware froze over.

Washington's plans to break a winter camp, split his hungry and ragged forces, cross an ice-choked river, and outflank and drive a far superior and powerful enemy away from liberty's doorstep proved to be more than his opposition expected.

The loading at McKonkeyâs Ferry on December 25 (now known as Washingtonâs Crossing) did not go according to plan. Washington had hoped to get everyone across including cannon by midnight, but a winter storm and the ice in the river impeded the crossing so that it was nearly four in the morning before his 2,400 men were marching south. The crossing itself was commanded by Washington's chief artillery officer, Henry Knox, who lined the western banks of the Delaware River with artillery.

As if arriving far behind the scheduled time of 5:00 a.m. was not bad enough, the weather which had been bad turned its full fury against them. On that march, Washingtonâs men, two divisions of hungry, tired, ill-clothed soldiers encountered every form of foul and discouraging weather imaginable. Yet the snow, ice, sleet, rain, wind, and even hail the heavens hurled at him and his men could not dampen Washingtonâs resolve. Knowing that he had everything to lose by not pressing the attack, he urged his men forward arriving at Trenton where he discovered the Hessians, who were fully expected to be waiting, were indeed yet asleep. The very elements which seemed to conspire against Washington, lulled the Hessians' sense of security even deeper and muffled the advance of Washington's men.

On December 27, Washington reported to the President of Congress, John Hancock, headquartered north of Philadelphia in Newton, Pennsylvania, that he despaired of arriving in time to surprise the Hessians. He also knew he was too late for any organized retreat back across the Delaware. With no turning back, He ordered his generals to lead the assault by the lower River Road and the upper Pennington Road. The distance being equal, the two divisions would arrive simultaneously and prevent the forming of an ordered defense. The force on the upper road led by General Stephenâs brigade and supported by Major General Greeneâs two brigades arrived exactly at 8:00 a.m. Three minutes later the division led by Major General Sullivan traveling the River Road arrived.

The Battles of Trenton and Princeton

The battle that ensued was swift. Within 30 minutes of furious fighting the Hessian garrison surrendered. The Hessians that escaped to the south were met and routed by Cadwalladerâs force which finally managed to cross with both men and some artillery on December 27. Cadwallader, believing Washington to be still in New Jersey when he crossed the Delaware, pressed onward to the north and east encountering the regrouping Hessians at Bordentown. General Ewing was unable to cross despite heroic efforts, but secured the bridge to Pennsylvania, preventing any escape along that route with the aid of the artillery brigade commanded by Henry Knox,.

In concluding his report of December 27 to the President of Congress, George Washington stated:

Our loss is very trifling indeed, only two Officers and one or two privates wounded. I find, that the Detachment of the Enemy consisted of the three Hessian Regiments of Lanspatch, Kniphausen and Rohl amounting to about 1500 Men, and a Troop of British Light Horse, but immediately upon the beginning of the Attack, all those who were, not killed or taken, pushed directly down the Road towards Bordentown. These would likewise have fallen into our hands, could my plan have been completely carried into Execution. Gen. Ewing was to have crossed before day at Trenton Ferry, and taken possession of the Bridge leading out of Town, but the Quantity of Ice was so great, that tho' he did every thing in his power to effect it, he could not get over.

This difficulty also hindered General Cadwallader from crossing, with the Pennsylvania Militia, from Bristol, he got part of his Foot over, but finding it impossible to embark his Artillery, he was obliged to desist. I am fully confident, that could the Troops under Generals Ewing and Cadwallader have passed the River, I should have been able, with their Assistance, to have driven the Enemy from all their posts below Trenton. But the Numbers I had with me, being inferior to theirs below me, and a strong Battalion of Light Infantry at Princetown above me, I thought it most prudent to return the same Evening, with my prisoners and the Artillery we had taken. We found no Stores of any Consequence in the Town. In justice to the Officers and Men, I must add, that their Behaviour upon this Occasion, reflects the highest honor upon them. The difficulty of passing the River in a very severe Night, and their march thro' a violent Storm of Snow and Hail, did not in the least abate their Ardour. But when they came to the Charge, each seemed to vie with the other in pressing forward, and were I to give a preference to any particular Corps, I should do great injustice to the others.[5]

The famous victory at Trenton was followed one week later on January 4, with a victory at the Battle of Princeton. These two victories breathed new life into the cause that eventually became the United States of America. Although he had little idea then of the enormity of the success his resolve bought, George Washington, believing to be providentially guided, followed through with his mission. The difficult conditions, from the locals who believed the revolution all but over and the British wrath fast upon them, to the impossible odds and even creation itself seeming to turn against him, did not sway him for one minute. The great victories clearly were snatched from the jaws of defeat.

The result among the populace and the men in the field is best described in this report on the Battle of Princeton:

- Although now General Cadwallader had not been able to pass the Delaware at the appointed time, yet, believing that General Washington was still on the Jersey side, on the 27th he crossed the river with fifteen hundred men, about two miles above Bristol; and even after he was informed that General Washington had again passed into Pennsylvania, he proceeded to Burlington, and next day marched on Bordentown, the enemy hastily retiring as he advanced.

- The spirit of resistance and insurrection was again fully awakened in Pennsylvania, and considerable numbers of the militia repaired to the standard of the commander-in-chief, who again crossed the Delaware and marched to Trenton, where, at the beginning of January, he found himself at the head of five thousand men.[6]

Conclusion

The British Field Commander in New Jersey during December 1776 and January 1777, Charles Cornwallis, was the commander of the British forces in 1781 during the final siege at the battle of Yorktown, Virginia. Although absent from the surrender ceremony, he observed to George Washington, "This is a great victory for you, but your brightest laurels will be writ upon the banks of the Delaware."

Notes

- â To COLONEL SAMUEL GRIFFIN Head Quarters, December 23, 1776. The writings of George Washington, Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- â To MAJOR GENERAL JOSEPH SPENCER Camp above the Falls of Trenton, December 22, 1776., The writings of George Washingon, Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- â To LUND WASHINGTON Falls of Delaware, South Side, December 10, 1776., The writings of George Washington, Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- â To ROBERT MORRIS Camp above the Falls, at Trenton, December 22, 1776, the writings of George Washington,Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- â George Washington Lettter, Animated Atlas, the Revolutionary War, Retrieved December 14, 2007.

- â battle of Princeton, Thrilling Incidents In American History, Retrieved December 14, 2007.

External Links

All links retrieved May 3, 2023.

- The Battle of Long Island - British Battles web page

- The Battle of Princeton

- The Battle of Princeton - British Battles web page

- The Battle of Trenton - British Battles web page

Credits

This article began as an original work prepared for New World Encyclopedia by Robert Brooks and is provided to the public according to the terms of the New World Encyclopedia:Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Any changes made to the original text since then create a derivative work which is also CC-by-sa licensed. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.