| Whig Party | |

|---|---|

| Founder(s) | Henry Clay |

| Founded | 1832 |

| Disbanded | 1856 |

| Political ideology | Modernization, Economic protectionism |

The Whig Party was a political party of the United States during the era of Jacksonian democracy. Considered integral to the Second Party System and operating from 1832 to 1856, the party was formed to oppose the policies of President Andrew Jackson and the Democratic Party. In particular, the Whigs supported the supremacy of Congress over the Executive Branch and favored a program of modernization and economic development. Their name was chosen to echo the American Whigs of 1776 who fought for independence.

The Whig Party counted among its members such national political luminaries as Daniel Webster, William Henry Harrison, and their pre-eminent leader, Henry Clay of Kentucky. In addition to Harrison, the Whig Party also counted four war heroes among its ranks, including generals Zachary Taylor and Winfield Scott. Abraham Lincoln was a Whig leader in frontier Illinois.

The Whig Party saw four of their candidates elected president: William Henry Harrison, John Tyler, Zachary Taylor and Millard Fillmore. Harrison died in office leaving Tyler to be president. Four months after succeeding Harrison, Whig President John Tyler was expelled from the party, and Millard Fillmore was the last Whig to hold the nation's highest office.

The party was ultimately destroyed by the question of whether to allow the expansion of slavery to the territories. Deep fissures in the party on this question led the party to run Winfield Scott over its own incumbent President Fillmore in the U.S. presidential election of 1852. The Whig Party never elected another president. Its leaders quit politics or changed parties. The voter base defected to the Republican Party, various coalition parties in some states, and to the Democratic Party.

Party structure

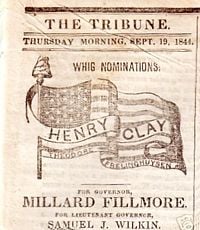

Rejecting the party loyalty that was the hallmark of tight Democratic Party organization, the Whigs suffered greatly from factionalism throughout their existence. On the other hand, the Whigs had a superb network of newspapers that provided an internal information system; their leading editor was Horace Greeley of the powerful New York Tribune. In their heyday in the 1840s, the Whigs won 46,846 votes with strong support in the manufacturing northeast and the border states. However, the Democratic Party grew more quickly over time, and the Whigs lost more and more marginal states and districts. After the closely contested 1844 elections, the Democratic advantage widened, and the Whigs were only able to win nationally by splitting the opposition. This was partly because of the increased political importance of the western states, which generally voted for Democrats, and Irish Catholic and German immigrants, who also tended to vote for Democrats.

The Whigs, also known as "the whiggery," won votes in every socio-economic category, but appealed more to the professional and business classes. In general, commercial and manufacturing towns and cities voted Whig, save for strongly-Democratic precincts. The Democrats often sharpened their appeal to the poor by ridiculing the Whigs' aristocratic pretensions. Protestant religious revivals also injected a moralistic element into the Whig ranks. Many called for public schools to teach moral values; others proposed prohibition to end the liquor problem.

The early years

In the 1836 elections, the party was not yet sufficiently organized to run one nationwide candidate; instead William Henry Harrison ran in the northern and border states, Hugh Lawson White ran in the South, and Daniel Webster ran in his home state of Massachusetts. It was hoped that the Whig candidates would amass enough U.S. Electoral College votes among them to deny a majority to Martin Van Buren, which under the United States Constitution would place the election under control of the House of Representatives, allowing the ascendant Whigs to select the most popular Whig candidate as president. The tactic failed to achieve its objective.

In 1839, the Whigs held their first national convention and nominated William Henry Harrison as their presidential candidate. Harrison went on to victory in 1840, defeating Van Buren's re-election bid largely as a result of the Panic of 1837 and subsequent depression. Harrison served only 31 days and became the first president to die in office. He was succeeded by John Tyler, a Virginian and states' rights absolutist. Tyler vetoed the Whig economic legislation and was expelled from the party in 1841. The Whigs' internal disunity and the nation's increasing prosperity made the party's activist economic program seem less necessary, and led to a disastrous showing in the 1842 Congressional elections.

A brief golden age

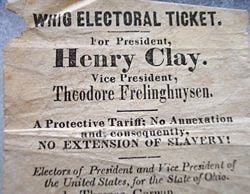

By 1844, the Whigs began their recovery by nominating Henry Clay, who lost to Democrat James K. Polk in a closely contested race, with Polk's policy of western expansion (particularly the annexation of Texas) and free trade triumphing over Clay's protectionism and caution over the Texas question. The Whigs, both northern and southern, strongly opposed expansion into Texas, which they (including Whig Congressman Abraham Lincoln) saw as an unprincipled land grab; however, they were split (as were the Democrats) by the anti-slavery Wilmot Proviso of 1846. In 1848, the Whigs, seeing no hope of success by nominating Clay, nominated General Zachary Taylor, a Mexican-American War hero. They stopped criticizing the war and adopted no platform at all. Taylor defeated Democratic candidate Lewis Cass and the anti-slavery Free Soil Party, who had nominated former President Martin Van Buren. Van Buren's candidacy split the Democratic vote in New York, throwing that state to the Whigs; at the same time, however, the Free Soilers probably cost the Whigs several Midwestern states.

Compromise of 1850

Taylor was firmly opposed to the Compromise of 1850, committed to the admission of California as a free state, and had proclaimed that he would take military action to prevent secession. But, in July 1850, Taylor died; Vice President Millard Fillmore, a long-time Whig, became president and helped push the compromise through Congress, in the hopes of ending the controversies over slavery. The Compromise of 1850 was first proposed by Clay.

Death throes, 1852–1856

The Whigs were near collapse in 1852; the deaths of Henry Clay and Daniel Webster that year severely weakened the party. The Compromise of 1850 fractured the Whigs along pro- and anti-slavery lines, with the anti-slavery faction having enough power to deny Fillmore the party's nomination in 1852. Attempting to repeat their earlier successes, the Whigs nominated popular General Winfield Scott, who lost decisively to the Democrats' Franklin Pierce. The Democrats won the election by a large margin: Pierce won 27 of the 31 states including Scott's home state of Virginia. Whig representative Lewis D. Campbell of Ohio was particularly distraught by the defeat, exclaiming, "We are slayed. The party is dead—dead—dead!" Increasingly politicians realized that the party was a defeated. For example, Abraham Lincoln, its Illinois leader, simply walked away and attended to his law business.

In 1854, the Kansas-Nebraska Act exploded on the scene. Southern Whigs generally supported the Act while Northern Whigs strongly opposed it. Most remaining Northern Whigs, like Lincoln, joined the new Republican Party and strongly attacked the Act, appealing to widespread northern outrage over the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. Other Whigs in 1854 joined the Know-Nothing Party, attracted by its nativist crusades against "corrupt" Irish and German immigrants.

In the South, the Whig party vanished, but as Thomas Alexander has shown, Whiggism as a modernizing policy orientation persisted for decades. Historians estimate that, in the South in 1856, Fillmore retained 86 percent of the 1852 Whig voters. He won only 13 percent of the northern vote, though that was just enough to tip Pennsylvania out of the Republican column. The future in the North, most observers thought at the time, was Republican. No one saw any prospects for the shrunken old party, and after 1856 there was virtually no Whig organization left anywhere.

In 1860, many former Whigs who had not joined the Republicans regrouped as the Constitutional Union Party, which nominated only a national ticket; it had considerable strength in the border states, which feared the onset of civil war. John Bell finished third. During the latter part of the war and Reconstruction, some former Whigs tried to regroup in the South, calling themselves "Conservatives," and hoping to reconnect with ex-Whigs in the North. They were soon swallowed up by the Democratic Party in the South, but continued to promote modernization policies such as railroad building and public schools.

In contemporary discourse, the Whig Party is usually mentioned in the context of a now-forgotten party losing its followers and reason for being. Parties sometimes accuse other parties of "going the way of the Whigs."

Presidents from the Whig Party

Whig presidents of the United States and dates in office:

- William Henry Harrison (1841)

- John Tyler (1841-1845) (see note below)

- Zachary Taylor (1849-1850)

- Millard Fillmore (1850-1853)

Although Tyler was elected vice president as a Whig, his policies soon proved to be opposed to most of the Whig agenda, and he was officially expelled from the party in 1841, a few months after taking office.

Additionally, John Quincy Adams, elected president as a Democratic Republican, later became a Whig when he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1831.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Brown, Thomas. Politics and Statesmanship: Essays on the American Whig Party. New York: Columbia University Press, 1985. ISBN 978-0231056021

- Egerton, Douglas R. Charles Fenton Mercer and the Trial of National Conservatism. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1989. ISBN 978-0878053926

- Holt, Michael F. To Rescue Public Liberty: A History of the American Whig Party. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 978-0195055443

- Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York: Oxford University Press, 1999. ISBN 9780-195055443

- Lutz, Donald S. Popular Consent and Popular Control: Whig Political Theory in the Early State Constitutions. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1980. ISBN 9780807105962

- Smith, W. Wayne. Anti-Jacksonian Politics Along the Chesapeake. Dissertations in Nineteenth-Century American Political and Social History. New York: Garland Pub., 1989. ISBN 978-0824040741

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.