AIDS is an acronym for acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Originating in sub-Saharan Africa during the twentieth century, it is now a global epidemic (pandemic), causing over 3 million deaths each year. AIDS is a collection of symptoms and opportunistic infections resulting from the depletion of the immune system caused by infection with the human immunodeficiency virus, or HIV. When the disease exhibits the symptoms of AIDS, its course is almost inevitably fatal; however treatments with retroviral drugs can slow the underlying HIV infection and delay the onset of full-blown AIDS.

The HIV virus that is believed to cause AIDS is transmitted through sexual relationships, sharing contaminated needles, blood transfusions, mishandling contaminated blood, as well as during pregnancy, childbirth, and breastfeeding. But primarily, HIV is transmitted through sexual relationships with an infected partner. Therefore, HIV/AIDS is both a medical and a moral concern. Effective prevention strategies need to take into account both dimensions of the disease.

The moral aspect has made it difficult for public authorities to deal with the AIDS pandemic by an entirely medical approach. The "culture wars" over religion and sexuality have divided public health authorities into opposing camps. One camp emphasizes the use of condoms to reduce the likelihood that sexual activity will transmit the virus. The other camp seeks behavior change‚ÄĒthat people limit their sexual activity to their marriage partner‚ÄĒas the key to solving the pandemic. Success with the latter strategy requires governments to partner with religious institutions to effectively educate and motivate the populace. An example of an effective comprehensive program that integrates both approaches is the "ABC model," developed first in Uganda and now recognized as a model of successful policy.

Global epidemic

The Joint United Nations Programme of HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO) estimate that 40.3 million people (between 36.7 and 45.3 million people) around the world were living with HIV in December 2005, including 2.3 million children. It was estimated that during 2005, between 4.3 and 6.6 million people were newly infected with HIV and between 2.8 and 3.6 million people with AIDS died. The number of new infections is still far out-pacing the number of deaths and "the AIDS epidemic continues to outstrip global efforts to contain it" (UNAIDS and WHO 2005).

Sub-Saharan Africa remains by far the worst-affected region, with approximately 25.8 million people living with HIV at the end of 2005. Two-thirds of all people living with HIV are in sub-Saharan Africa, as are 77 percent of all women with HIV. South and Southeast Asia are the second-most affected regions with about 18.4 percent of the total number of people living with HIV (approximately 7.4 million people).

| World region | Estimated adult prevalence of HIV infection (ages 15‚Äď49) |

Estimated adult and child deaths during 2005 |

|---|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | ||

| Caribbean | ||

| South and Southeast Asia | ||

| East Asia | ||

| Eastern Europe and Central Asia | ||

| Latin America | ||

| Oceania | ||

| North Africa and Middle East | ||

| North America | ||

| Western Europe and Central Europe |

Source: UNAIDS and the WHO 2005 estimates. The ranges define the boundaries within which the actual numbers lie, based on the best available information.

Origin

The official date for the beginning of the AIDS epidemic is marked as June 18, 1981, when the United States Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a cluster of Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (now classified as Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia) in five gay men in Los Angeles. Originally dubbed GRID, or Gay-Related Immune Deficiency, health authorities soon realized that nearly half of the people identified with the syndrome were not gay. In 1982, the CDC introduced the term AIDS to describe the newly recognized syndrome.

Nevertheless, scientists now believe that the HIV virus that causes AIDS had been infecting humans in Africa long before 1981; only the disease had not been recognized as AIDS. The most common view is that HIV mutated from a virus in chimpanzees, the simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV). Indeed, there are striking parallels between SIV infection of chimps and HIV infection of humans. A newer study suggests that HIV is a product of separate viruses jumping from different monkey species into chimps: the red-capped mangabey (Cercocebus torquatus) and the greater spot-nosed monkey (Cercopithecus nictitans). Chimps eat monkeys, which is likely how they acquired the monkey viruses. The hybrid virus then spread through the chimpanzee species, and was later transmitted to humans to become HIV-1. Monkeys (sooty mangabey monkeys) may also have passed the less virulent HIV-2 strain directly to humans (Lovgren 2003).

HIV

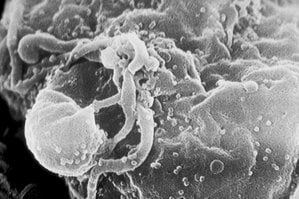

Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), the virus that is generally considered to cause AIDS, is a retrovirus that primarily infects vital components of the human immune system, such as CD4 positive T (CD4+ T) cells, macrophages, and dendritic cells. CD4+ T cells are T cells (a group of lymphocytes, or type of white blood cell) that expresses the surface protein CD4 and plays a cornerstone role in the immune system. Macrophages are cells in tissues that are involved in phagocytosis of pathogens and debris. Dendritic cells are immune cells that are part of the mammal immune system.

HIV directly and indirectly destroys CD4+ T cells. As CD4+ T cells are required for the proper functioning of the immune system, when enough CD4+ T cells have been destroyed by HIV, the immune system functions poorly, leading to the syndrome of AIDS. HIV also directly attacks organs, such as the kidneys, the heart, and the brain, leading to acute renal failure, cardiomyopathy, dementia, and encephalopathy. Many of the problems faced by people infected with HIV result from failure of the immune system to protect from opportunistic infections and cancers.

Classification of HIV

HIV is classified as a member of the genus Lentivirus of the family Retroviridae. Lentiviruses have many common morphologies and biological properties. Many species are infected by lentiviruses, which are characteristically responsible for long-duration illnesses associated with a long period of incubation (Lévy 1993). Lentiviruses are transmitted as single-stranded, positive-sense, enveloped RNA viruses. Upon infection of the target-cell, the viral RNA genome is converted to double-stranded DNA by a virally encoded reverse transcriptase that is present in the virus particle. This viral DNA is then integrated into the cellular DNA for replication using cellular machinery. Once the virus enters the cell, two pathways are possible: either the virus becomes latent and the infected cell continues to function or the virus becomes active, replicates, and a large number of virus particles are liberated that can infect other cells.

Two species of HIV infect humans: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is the more virulent and easily transmitted, and is the source of the majority of HIV infections throughout the world; HIV-2 is largely confined to West Africa (Reeves and Doms 2002). Both species originated in West and central Africa, jumping from primates to humans in a process known as zoonosis. HIV-1 has evolved from a simian immunodeficiency virus (SIV) found in the chimpanzee subspecies, Pan troglodytes troglodytes (Gao et al. 1999). HIV-2 crossed species from a different strain of SIV, found in sooty mangabey monkeys, an Old World monkey of Guinea-Bissau, Gabon, and Cameroon (Reeves and Doms 2002).

Origin, discovery and naming of HIV

Three of the earliest known instances of HIV infection are as follows:

- A plasma sample taken in 1959 from an adult male living in what is now the Democratic Republic of Congo.

- HIV found in tissue samples from an American teenager who died in St. Louis in 1969.

- HIV found in tissue samples from a Norwegian sailor who died around 1976.

In 1983, scientists led by Luc Montagnier at the Pasteur Institute in France first discovered the virus that is linked to AIDS (Barré-Sinoussi et al. 1983). They called it lymphadenopathy-associated virus (LAV). A year later a team led by Robert Gallo of the United States confirmed the discovery of the virus, but they renamed it human T lymphotropic virus type III (HTLV-III) (Popovic et al. 1984). The dual discovery led to considerable scientific "fall-out," and it was not until President Mitterand of France and President Reagan of the United States met that the major issues were ironed out. In 1986, both the French and the US names were dropped in favor of the new term human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) (Coffin 1986).

HIV structure and genome

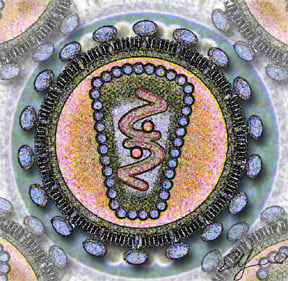

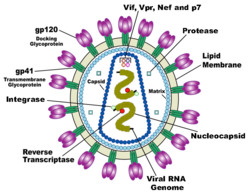

HIV is different in structure from previously described retroviruses. It is around 120 nm in diameter (120 billionths of a meter; around 60 times smaller than a red blood cell) and roughly spherical.

HIV-1 is composed of two copies of single-stranded RNA enclosed by a conical capsid, which is in turn surrounded by a plasma membrane that is formed from part of the host-cell membrane. Other enzymes contained within the virion particle include reverse transcriptase, integrase, and protease.

HIV has several major genes coding for structural proteins that are found in all retroviruses, and several nonstructural ("accessory") genes that are unique to HIV. The gag gene provides the physical infrastructure of the virus; pol provides the basic enzymes by which retroviruses reproduce; and the env gene supplies the proteins essential for viral attachment and entry into a target cell. The accessory proteins tat, rev, nef, vif, vpr, and vpu enhance virus production. Although called accessory proteins, tat and rev are essential for virus replication. In some strains of HIV, a mutation causes the production of an alternate accessory protein, Tev, from the fusion of tat, rev, and env.

The gp120 and gp41 proteins, both encoded by the env gene, enable the virus to attach to and fuse with target cells to initiate the infectious cycle. Both, especially gp120, have been considered as targets of future treatments or vaccines against HIV.

Critics of the HIV theory

That HIV is the causal agent of AIDS is regarded by most as a well-established fact, and prevention and treatment practices are based on this tenet. However, a number of scientists continue to question that HIV is the cause of AIDS. Peter H. Duesberg, a molecular biologist at the University of California, Berkeley, has published numerous articles countering the linkage in prominent journals, and authored or edited books such as Infectious AIDS: Have We Been Misled? (1995), Inventing the AIDS Virus (1996), and AIDS: Virus or Drug Induced? (1996). He and his supporters claim that HIV is a "passenger virus" not the cause‚ÄĒwhich could be heavy use of recreational drugs, the antiretroviral drugs prescribed to treat people who are HIV-positive, malnutrition, and bad water (Duesberg and Rasnick, 1998).

Symptoms

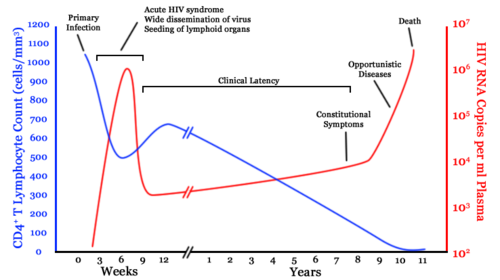

The clinical course of HIV infection generally includes three stages: primary infection, clinical latency, and AIDS.

Infection with HIV-1 is associated with a progressive loss of CD4+ T-cells. This rate of loss can be measured and is used to determine the stage of infection. When the T-cell count falls below 200 cells per cubic millimeter of blood, an HIV-infected person is said to have "contracted" AIDS. In a healthy adult, the T-cell count is usually 1,000 or more.

The loss of CD4+ T-cells is linked with an increase in viral load. HIV plasma levels during all stages of infection range from just 50 up to 11 million virions per ml (Piatak et al. 1993).

Primary Infection

Primary or acute infection is a period of rapid viral replication that immediately follows the individual's exposure to HIV.

When first infected by HIV, most people will not have any symptoms. Within a month or two, during primary HIV infection, most individuals (80 to 90 percent) develop an acute syndrome characterized by flu-like symptoms of fever, malaise, swelling of lymph nodes (lymphadenopathy), sore throat (inflammation of the pharynx, or pharyngitis), headache, muscle pain (myalgia), and sometimes a rash (Kahn and Walker 1998). Within an average of three weeks after transmission of HIV-1, a broad HIV-1 specific immune response occurs that includes seroconversion, or the development of detectable, specific antibodies in the serum as a result of infection.

Because of the nonspecific nature of these illnesses, it is often not recognized as a sign of HIV infection. Even when patients go to their doctors or a hospital, they often are misdiagnosed as having one of the more common infectious diseases with the same symptoms. Since not all patients develop it, and since the same symptoms can be caused by many other common diseases, it cannot be used as an indicator of HIV infection. However, recognizing the syndrome is important because the patient is much more infectious during this period.

Clinical Latency

As a result of the strong immune defense, the number of viral particles in the blood stream declines and the patient enters clinical latency. Severe and persistent symptoms may not appear for more than a decade. This ‚Äúasymptomatic‚ÄĚ period varies widely in duration between individuals, with clinical latency ranging from two weeks to 20 years. During this phase, HIV is active within lymphoid organs where large amounts of virus become trapped in the follicular dendritic cells (FDC) network early in HIV infection. The surrounding tissues that are rich in CD4+ T-cells also become infected, and viral particles accumulate both in infected cells and as free virus. Individuals who have entered into this phase are still infectious.

AIDS symptoms

AIDS is the most severe manifestation of infection with HIV. As complications begin to set in, the lymph nodes enlarge. This may last for more than three months and be accompanied with other symptoms including: loss of weight and energy, frequent fevers and sweats, persistent or frequent yeast infections, skin rashes, and short-term memory loss (NIAID 2005).

In people living with AIDS (PLWA), the immune system is so ravaged by HIV that the body can no longer defend itself. Bacteria, viruses, fungi, parasites, and other opportunistic infections go almost unchecked. Common symptoms of PLWA include:

- Coughing and shortness of breath

- Seizures and lack of coordination

- Mental confusion and forgetfulness

- Persistent diarrhea

- Fever

- Vision loss

- Nausea and vomiting

- Weight loss and extreme fatigue

- Severe headaches

- Coma

Many PLWA become debilitated and cannot hold a job or do work at home. However, a small number of people infected with HIV never develop AIDS. They are being studied by scientists to determine why, although they have HIV, their infection has not progressed into AIDS (NIAID 2005).

Transmission and infection

Since the beginning of the epidemic, three main transmission routes of HIV have been identified:

- Sexual route. The majority of HIV infections are acquired through unprotected sexual relations. Sexual transmission occurs when there is contact between sexual secretions of one partner with the rectal, genital, or mouth mucous membranes of another. According to the French ministry for health, the probability of transmission per act varies from 0.03 percent to 0.07 percent for the case of receptive vaginal sex, from 0.02 to 0.05 percent in the case of insertive vaginal sex, from 0.01 to 0.185 percent in the case of insertive anal sex, and from 0.5 to 3 percent in the case of receptive anal sex.

- Blood or blood product route. This transmission route occurs primarily with intravenous drug users, hemophiliacs, and recipients of blood transfusions and blood products. It is of concern for persons receiving medical care in regions where there is prevalent substandard hygiene in the use of injection equipment (e.g. reused needles in Third World settings). Health care workers (nurses, laboratory workers, doctors, etc.) are also directly concerned, although more rarely. Concerned too by this route are people who give and receive tattoos, piercings, and scarification procedures.

- Mother-to-child route. The transmission of the virus from the mother to the child can occur in utero during the last weeks of pregnancy and at childbirth. Breast feeding also presents a risk of infection for the baby. In the absence of treatment, the transmission rate between the mother and child is roughly 20 percent. However, where treatment is available, combined with the availability of Cesarian sections, this can been reduced to 1 percent.

HIV has been found at low concentrations in the saliva, tears, and urine of infected individuals, but the risk of transmission by these secretions is considered to be negligible.

Patterns of HIV transmission vary in different parts of the world. In sub-Saharan Africa, which accounts for an estimated 60 percent of new HIV infections worldwide, controversy rages over the respective contribution of medical procedures, heterosexual sex, and the bush meat trade. In the United States, sex between men (35 percent) and needle sharing by intravenous drug users (15 percent) remain prominent sources of new HIV infections. In January 2005, Anthony S. Fauci, M.D., director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) said, "Individual risk of acquiring HIV and experiencing rapid disease progression is not uniform within populations."

Some epidemiological models suggest that over half of HIV transmission occurs in the weeks following primary HIV infection before antibodies to the virus are produced. Investigators have shown that viral loads are highest in semen and blood in the weeks before antibodies develop and estimated that the likelihood of sexual transmission from a given man to a given woman would be increased about twenty-fold during primary HIV infection as compared with the same couple having the same sex act 4 months later.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in the United States reported a cluster of HIV infections in 13 of 42 young women who reported sexual contact with the same HIV-infected man in a rural county in upstate New York between February and September 1996.

The risk of oral sex has always been controversial. Most of the early AIDS cases could be attributed to anal sex or vaginal sex. As the use of condoms became more widespread, there were reports of AIDS acquired by oral sex. Unprotected oral sex is widely understood to be less risky than unprotected vaginal sex, which in turn is less risky than unprotected anal sex.

Heterosexual transmission of HIV-1 depends on the infectiousness of the index case and the susceptibility of the uninfected partner. Infectivity seems to vary during the course of illness and is not constant between individuals. Each tenfold increment of seminal HIV RNA is associated with an 81 percent increased rate of HIV transmission. During 2003 in the United States, 19 percent of new infections were attributed to heterosexual transmission.

The argument about the exact probability of HIV transmission per act of intercourse is academic. Infectivity depends critically on social, cultural, and political factors as well as the biological activity of the agent. Whether the epidemic grows or slows depends on infectivity plus two other variables: the duration of infectiousness and the average rate at which susceptible people change sexual partners.

Genetic susceptibility

The CDC has released findings that genes influence susceptibility to HIV infection and progression to AIDS. HIV enters cells through an interaction with both CD4 and a chemokine receptor of the 7 Tm family. They first reviewed the role of genes in encoding chemokine receptors (CCR5 and CCR2) and chemokines (SDF-1). While CCR5 has multiple variants in its coding region, the deletion of a 32-bp segment results in a nonfunctional receptor, thus preventing HIV entry. Two copies of this gene provide strong protection against HIV infection, although the protection is not absolute. This gene is found in up to 20 percent of Europeans, but is rare in Africans and Asians. Researchers and scientists believe that HIV had a similar viral shell as the bacteria which caused the Black Plague (1347 ‚Äď 1350), leading to the decimation of one-third of the European population, possibly explaining why the CCR5-32 receptor gene is more prevalent in Europeans than Africans and Asians. Multiple studies of HIV-infected persons have shown that presence of one copy of this gene delays progression to the condition of AIDS by about 2 years. And it is possible that a person with the CCR5-32 receptor gene will not develop AIDS, although they will still carry HIV.

Prevention

As with all diseases, prevention is better than cure. This is all the more true for HIV/AIDS because, although treatments exist that will slow the progression from HIV to AIDS, there is currently no known cure or vaccine.

The most effective method for preventing HIV/AIDS requires a two-pronged approach: strengthening moral values for the general population, and targeting high risk groups (sex traffickers, drug users, and those likely to engage in promiscuous sex) with barrier devices such as condoms.

ABC Model

According to a report from the U.S. Agency for International Development, there is only one country in the world that has substantially turned back the HIV/AIDS pandemic.

Uganda is the standout among countries that have effectively responded to HIV/AIDS under the guidance of national leadership in both the political and religious realms. Uganda has experienced the most significant decline in HIV prevalence of any country in the world (Green 2003).

Uganda‚Äôs model, developed indigenously, is called the "ABC model." Here "A" stands for Abstinence, "B" for Be faithful, and "C" for Condoms (used correctly and consistently). Importantly, equal emphasis was not given to each component. Ugandans put the primary emphasis on "A" and "B," while condom distribution continued through the Ministry of Health under a ‚ÄúPolicy of Silent Promotion‚ÄĚ (Dyer 2003).

The Vatican and other religious groups oppose the use of condoms. Nonetheless, having a dual approach to HIV/AIDS prevention allows both the faith-based organizations and the medical community to work towards a common goal. This ABC model made it possible for the faith-based communities to be fully engaged in HIV/AIDS prevention without violating their theologies. Religious groups focused on "A" and "B," while health care professionals focused on "C." Both benefited from this specialization.

Religious communities have vast networks that reach into the most rural areas. They can be powerful agents for behavioral and social change, they have resources to mobilize large numbers of volunteers, and they have experience in health care and education. Their full participation in HIV/AIDS prevention was essential in Uganda’s success.

It was important that the condom message be specifically targeted and not mass marketed. Separating "A" and "B" from "C" helped the condom message be "very effective" in high-risk groups (Green et al. 2005). By having a well-defined small target, condom use could be more effectively monitored, including the needed education and training. Importantly, this small focus did not undermine the message to the general population that human sexuality should be an exclusive act of marriage.

Uganda's model has been heavily scrutinized and well documented. In a generalized heterosexual population, HIV prevalence declined nearly 70 percent since the early 1990s. Importantly, it was accompanied with a 60 percent reduction in casual sex. The decline of HIV prevalence in 15 to 19 year-olds was 75 percent and was seen as a key to Uganda’s success. The annual cost was $1 per person aged 15 and above. If this ABC program had been implemented throughout sub-Saharan Africa by 1996, it is estimated that there would be 6 million fewer persons infected with HIV and 4 million fewer children would have been orphaned (Green et al. 2005).

CNN approach

Another widely used approach to HIV/AIDS prevention is the CNN Approach. This is:

- Condom use, for those who engage in risky behavior.

- Needles, use clean ones

- Negotiating skills; negotiating safer sex with a partner and empowering women to make smart choice

Thailand is seen as an example of a successful mass marketing strategy against HIV/AIDS. Starting in the early 1990s, the Thai government implemented a tough policy that mandated condom use for all commercial sex workers. However, there was another behavior change working in tandem with the strong push from the government. The decline in HIV/AIDS in Thailand had two contributing factors: increased condom usage and the reduction in the number of sex partners. There was "a 60 percent decline in visits to sex workers" and "the proportion of men reporting casual sex during the past 12 months declined 46 percent, from 28 percent in 1990 to 15 percent in 1993" (Green et al. 2005).

Preventing mother to child transmission

There is a 15 to 30 percent risk of transmission of HIV from mother to child during pregnancy, labor, and delivery. A number of factors influence the risk of infection, particularly the viral load of the mother at birth (the higher the load, the higher the risk). Breastfeeding increases the risk of transmission by 10 to 15 percent. This risk depends on clinical factors and may vary according to the pattern and duration of breastfeeding.

Studies have shown that antiretroviral drugs, cesarean delivery, and formula feeding reduce the chance of transmission of HIV from mother to child (Sperlin et al. 1996).

When replacement feeding is acceptable, feasible, affordable, sustainable, and safe, HIV-infected mothers are recommended to avoid breast feeding their infant. Otherwise, exclusive breastfeeding is recommended during the first months of life and should be discontinued as soon as possible.

Treatment

There is currently no cure or vaccine for HIV or AIDS.

According to some, the optimal treatment consists of a combination ("cocktail") consisting of at least three drugs belonging to at least two types, or "classes," of anti-retroviral agents. Typical regimens consist of two nucleoside analogue reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) plus either a protease inhibitor or a non nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI). This treatment is frequently referred to as HAART (highly-active anti-retroviral therapy).

Anti-retroviral treatments, along with medications intended to prevent AIDS-related opportunistic infections, have played a part in delaying complications associated with AIDS, reducing the symptoms of HIV infection, and extending patients' life spans. Over the past decade, the success of these treatments in prolonging and improving the quality of life for people with AIDS has improved dramatically.

Side effects

HAART is beneficial, but there are side effects, some severe, associated with the use of antiviral drugs. When taken in the later stages of the disease, some of the nucleoside RT inhibitors may cause a decrease of red or white blood cells. Some may also cause inflammation of the pancreas and painful nerve damage. There have been reports of complications and other severe reactions, including death, to some of the antiretroviral nucleoside analogs when used alone or in combination. Therefore, health care experts recommend that people be routinely seen and monitored by health care providers if they are on antiretroviral therapy.

The most common side effects associated with protease inhibitors include nausea, diarrhea, and other gastrointestinal symptoms. In addition, protease inhibitors can interact with other drugs resulting in serious side effects. Fuzeon may also cause severe allergic reactions such as pneumonia, trouble breathing, chills and fever, skin rash, blood in urine, vomiting, and low blood pressure. Local skin reactions are also possible since it is given as an injection underneath the skin.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Barr√©-Sinoussi, F., J. C. Chermann, F. Rey, M. T. Nugeyre, S. Chamaret, J. Gruest, C. Dauguet, C. Axler-Blin, F. Vezinet-Brun, C. Rouzioux, W. Rozenbaum, and L. Montagnier. 1983. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS). Science 220:868‚Äď871.

- Carr, J. K., B. T. Foley, T. Leitner, M. Salminen, B. Korber, and F. McCutchan. 1998. Reference Sequences Representing the Principal Genetic Diversity of HIV-1 in the Pandemic. In Los Alamos National Laboratory, ed. HIV Sequence Compendium, pp. 10‚Äď19.

- Chan, D. C. and P. S. Kim 1998. HIV entry and its inhibition. Cell 93:681‚Äď684

- Coakley, E., C. J. Petropoulos, and J. M. Whitcomb. 2005. Assessing chemokine co-receptor usage in HIV. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 18:9‚Äď15.

- Coffin, J., A. Haase, J. A. Levy, L. Montagnier, S. Oroszlan, N. Teich, H. Temin, K. Toyoshima, H. Varmus, P. Vogt, and R. A. Weiss. 1986. What to call the AIDS virus? Nature 321:10.

- Duesberg, P. H. 1987. Retroviruses as carcinogens and pathogens: expectations and reality. Cancer Research 47:1199‚Äď1220.

- Duesberg, P. H. 1995. Infectious AIDS: Have we been Misled? North Atlantic Books.

- Duesberg, P. H. (Ed.) 1996. AIDS: Virus or Drug Induced? Contemporary Issues in Genetics and Evolution, Vol. 5. Kluwer Academics Publishers.

- Duesberg, P. H. 1996. Inventing the AIDS Virus. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing.

- Duesberg, P. H., and D. Rasnick. 1998. The AIDS dilemma: drug diseases blamed on a passenger virus. Genetica 104:85‚Äď132.

- Duesberg, P. H., C. Koehlein, and D. Rasnick. 2003. The chemical bases of the various AIDS epidemics: recreational drugs, anti-viral chemotherapy, and malnutrion. Journal of Bioscience 28(4):383‚Äď412.

- Dyer, E. 2003. And Banana Trees Provided the Shade. Kampala, Uganda: Ugandan AIDS Commission.

- Gao, F., E. Bailes, D. L. Robertson, Y. Chen, C. M. Rodenburg, S. F. Michael, L. B. Cummins, L. O. Arthur, M. Peeters, G. M. Shaw, P. M. Sharp, and B. H. Hahn. 1999. Origin of HIV-1 in the Chimpanzee Pan troglodytes troglodytes. Nature 397:436‚Äď441.

- Gelderblom, H. R. 1997. Fine structure of HIV and SIV. In Los Alamos National Laboratory (Ed) HIV Sequence Compendium, 31‚Äď44.

- Gendelman, H. E., W. Phelps, L. Feigenbaum, J. M. Ostrove, A. Adachi, P. M. Howley, G. Khoury, H. S. Ginsberg, and M. A. Martin. 1986. Transactivation of the human immunodeficiency virus long terminal repeat sequences by DNA viruses. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 83: 9759‚Äď9763.

- Green, E. C. 2003. Faith-Based Organizations: Contributions to HIV Prevention. Washington, DC: U.S. Agency for International Development, Synergy Project.

- Green, E. C., R. L. Stoneburner, D. Low-Beer, N. Hearst, and S. Chen. 2005. Evidence That Demands Action: Comparing Risk Avoidance and Risk Reduction Strategies for HIV Prevention. Austin, TX: Medical Institute.

- Kahn, J. O. and B. D. Walker. 1998. Acute Human Immunodeficiency Virus type 1 infection. N Engl J Med 331:33‚Äď39.

- Knight, S. C., S. E. Macatonia, and S. Patterson. 1990. HIV I infection of dendritic cells. Int Rev Immunol. 6:163‚Äď75.

- L√©vy, J. A. 1993. HIV pathogenesis and long-term survival. AIDS 7:1401‚Äď1410.

- NIAID (National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases). 2005. HIV Infection and AIDS: An Overview. Washington, DC: Courtesy: National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (http://www.niaid.nih.gov/factsheets/hivinf.htm).

- Lovgren, Stefan. "HIV Originated With Monkeys, Not Chimps, Study Finds," National Geographic News, June 12, 2003. Retrieved September 7, 2012.

- Mullis, K. 1998. Dancing Naked in the Mind Field. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Osmanov, S., C. Pattou, N. Walker, B. Schwardlander, J. Esparza, and the WHO-UNAIDS Network for HIV Isolation and Characterization. 2002. Estimated global distribution and regional spread of HIV-1 genetic subtypes in the year 2000. J. Acquir. Immune. Defic. Syndr. 29:184‚Äď190.

- Piatak, M., Jr., M. S. Saag, L. C. Yang, S. J. Clark, J. C. Kappes, K. C. Luk, B. H. Hahn, G. M. Shaw, and J. D. Lifson. 1993. High levels of HIV-1 in plasma during all stages of infection determined by competitive PCR. Science 259:1749‚Äď1754.

- Pollard, V. W. and M. H. Malim. 1998. The HIV-1 Rev protein. Annual Review of Microbiology 52:491‚Äď532.

- Popovic, M., M. G. Sarngadharan, E. Read, and R. C. Gallo. 1984. Detection, isolation, and continuous production of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and pre-AIDS. Science 224:497‚Äď500.

- Reeves, J. D., and R. W. Doms. 2002. Human immunodeficiency virus type 2. J. Gen. Virol. 83:1253‚Äď1265.

- Tang, J., and R. A. Kaslow. 2003. The impact of host genetics on HIV infection and disease progression in the era of highly active antiretroviral therapy. AIDS 17:S51‚ÄďS60.

- Thomson, M. M., L. Perez-Alvarez, and R. Najera. 2002. Molecular epidemiology of HIV-1 genetic forms and its significance for vaccine development and therapy. Lancet Infect Dis. 2:461‚Äď471.

- UNAIDS and WHO. 2005. AIDS epidemic update: December 2005. Joint United Nations Programme of HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) and the World Health Organization (WHO). (PDF Retrieved September 7, 2012.)

- Wyatt, R., and J. Sodroski. 1998. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science 280:1884‚Äď1888.

- Zheng, Y. H., N. Lovsin, and B. M. Peterlin. 2005. Newly identified host factors modulate HIV replication. Immunol Lett. 97:225‚Äď234.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.