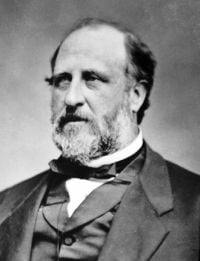

William M. Tweed

| William M. Tweed | |

| |

| In office March 4, 1853 – March 3, 1855 | |

| Preceded by | George Briggs |

|---|---|

| Succeeded by | Thomas R. Whitney |

| Born | April 3, 1823 New York, New York, USA |

| Died | April 12, 1878 New York, New York, USA |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Profession | Politician |

William M. "Boss" Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April12, 1878) was an American politician and head of Tammany Hall, the name given to the Democratic Party political machine that played a major role in the History of New York City politics from the 1790s to the 1960s. He was convicted and eventually imprisoned for embezzling millions of dollars from the city through political corruption and graft.

Political career

Tweed left school at the age of 11 to learn his father’s trade of chair making. At 13 he was apprenticed to a saddle maker, at 17 he worked as a bookkeeper for a brush company, and at 19 joined the firm; he later went on to marry the daughter of the firms chief owner. Tweed also joined the volunteer fire department. In 1850 he became the foreman of the Americus NO. 6 company, also know as the Big 6. One year later with their help, Tweed was elected Democratic alderman. In 1852, he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and served one term. Tweed's focus was then switched to local politics. His official positions included membership on the city board of supervisors, state senator, chairman of the state finance committee, school commissioner, deputy street commissioner, and commissioner of public works.

Tweed managed to provide legal services to corporations such as the Erie Railroad despite his limited knowledge of the law. Financiers Jay Gould and Big Jim Fisk made Boss Teed a director the Erie Railroad and Tweed in turn arranged favorable legislation for them. Tweed and Gould became the subjects of political cartoons by Thomas Nast in 1869. In April 1870, Tweed secured the passage of a city charter putting the control of the city into the hands of the mayor (A. Oakey Hall), the comptroller and the commissioners of parks and public works, he then set about to plunder the city. The total amount of money stolen was never known. It has been estimated from $25 million to $200 million. Over a period of two years and eight months, New York City’s debts increased from $36 million in 1868 to about $136 million by 1870, with little to show for the debt.

Tweed was now a millionaire and the third largest land owner in Manhattan. Tweed’s motto was “something for everyone.” He used this philosophy to corrupt newspaper reporters and to persuade union and Catholic Church officials to go along with his plans for civic improvement. Tweed defrauded the city by having contractors present excessive bills for work performed, typically ranging from 15 to 65 percent more than the project actually cost. As operations tightened Tweed and his gang saw to it that all bills to the city would be at least one-half fraudulent which later reached 85 percent. The proceeds where divided equally among Tweed, the city comptroller, county treasurer, the mayor with one-fifth set aside for official bribes. The most excessive overcharging came in the form of the famous Tweed Courthouse, which cost the city $13 million to construct. The actual cost for the court house was about three million, leaving about ten million for the pockets of Tweed and his gang. The city was also billed $3,000,000 for city printing and stationery over a two-year period. With the purchasing of the printing and marble companies, this enabled Tweed to further his control of the cities operations by providing the materials used in the building of the new courthouse. While he was known primarily for the vast corrupt empire, Tweed was also responsible for building hospitals, orphanages, widening Broadway along the Upper West Side, and securing the land for the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The public works projects where needed to provide services to the massive influx of European immigrants.

Tweed's arrest and subsequent flight

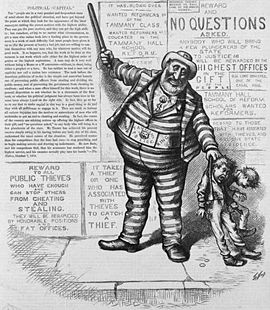

A Harper's Weekly cartoon depicts Tweed as a police officer saying to two boys, "If all the people want is to have somebody arrested, I'll have you plunderers convicted. You will be allowed to escape, nobody will be hurt, and then Tilden will go to the White House and I to Albany as Governor."

The New York Times published editorials raising questions about how Tweed and those associated with him where able to acquire such a vast amount of wealth. For a time, the newspaper lacked hard evidence. But, this would soon change. Tweed's demise was evident when one of the plunderers, dissatisfied with the amount of money he received, gave The New York Times evidence that conclusively proved that stealing was going on. The informant provided copies of a secret book that detailed the level of corruption. This evidence was reported to the public in the November 20, 1873 edition of the paper. The newspaper was apparently offered five million dollars to not publish the evidence. In a subsequent interview about the fraud, Tweed’s only reply was, “Well what are you going to do about it?” However, accounts in The New York Times and political cartoons drawn by Thomas Nast and published in Harper’s Weekly, resulted in the election of numerous opposition candidates in 1871. Tweed is attributed with what the papers say about me. "My constituents can’t read, but damn it, they can see pictures!” In October 1871, when Tweed was held on $8,000,000 bail, Jay Gould was the chief bondsman. The efforts of Political reformers William H. Wickham (1875 New York City mayor) and Samuel J. Tilden (later the 1876 Democratic presidential nominee) resulted in Tweed’s trial and conviction in 1873. He was given a 12 year prison sentence, which was reduced by a higher court and he served one year. He was then re-arrested on civil charges, sued by New York State for $6,000,000 and held in debtor’s prison until he could post $3,000,000 as bail. Tweed was still a wealthy man and his prison cell was somewhat luxurious. Tweed was allowed to visit his family on a daily basis and on December 4, 1875, Tweed escaped and fled to Cuba. His presence in Cuba was discovered by the U.S. Government and he was held by the Cuban government. Before the U.S. Government could arrange for his extradition, Tweed bribed his way onto a ship to Spain serving as a common seaman. Before he arrived, the U.S. Government discovered his eventual destination and arranged for his arrest as soon as he reached the Spanish coast. The Spanish authorities identified him, purportedly recognizing him from one of Nast’s cartoons and extradited him. He was delivered to the authorities in New York City on November 23, 1876. Ironically he was incarcerated at the Ludlow Street Jail just a few blocks from his childhood home. He died two years later after being very ill on April 12, 1878, at the age of 55. During Tweed's illness he offered to disclose everything he knew about Tammany Hall in exchange for his release but, was denied. He was buried in the Brooklyn Green-Wood Cemetery.

Trivia

- Boss Tweed was portrayed by Jim Broadbent in the 2002 film Gangs of New York.

- Tweed's middle name does not appear on any surviving documents. Tweed invariably gave his name as William M. Tweed on the many government orders he signed. The M must stand for Magear, the middle name of his son William Magear Tweed Jr, since a son named Junior has the same name as his father. Magear was Tweed's mother's maiden name. The oft-used but incorrect middle name Marcy originated in a joking reference to New York Governor William L. Marcy (1833-1838), the man who said "to the victor belongs the spoils." See Hershkowitz, below.

- Boss Tweed was of Scottish-Irish descent.

Tweed was a member of an organization called The Society of Saint Tammany, which was founded in 1789 and took its name from the chief of the Delaware Indians. It began as a charitable organization created by tradesman who where not allowed to join the clubs of the wealthy. The society provided food, shelter and jobs for the less fortunate.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Ackerman, Kenneth D. Boss Tweed: the rise and fall of the corrupt pol who conceived the soul of modern New York. New York: Carroll & Graf Publishers, 2005. ISBN 9780786714353

- Hershkowitz, Leo. Tweed's New York: Another Look, 1977.

- Lynch, Dennis Tilden. Boss Tweed: the story of a grim generation. New Brunswick N.J. Transaction Publishers January, 2002. ISBN 9780765809346

- Mandelbaum, Seymour J. Boss Tweed's New York, 1965. ISBN 0-471-56652-7

External links

All links retrieved October 4, 2020.

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.