William Hazlitt

William Hazlitt (April 10, 1778 – September 18, 1830) was an English writer remembered for his humanistic essays and literary criticism, often esteemed the greatest English literary critic after Samuel Johnson. Indeed, Hazlitt's writings and remarks on Shakespeare's plays and characters are rivaled only by those of Johnson in their depth, insight, originality, and imagination.

Background

Hazlitt came from a branch of Irish Protestant stock that moved in the reign of George I from the county of Antrim to Tipperary. His father, also a William Hazlitt, went to the University of Glasgow (where he was contemporary with Adam Smith), from which he received a master's degree in 1760. Not entirely content with his Presbyterian faith, he became a Unitarian, joined their ministry, and crossed over to England, where he could minister to other Unitarians. In 1764 he was pastor at Wisbech in Cambridgeshire, where in 1766 he married Grace Loftus, daughter of a recently deceased ironmonger. Of their many children, only three survived infancy. The first of these, John (later known as a portrait painter) was born in 1767 at Marshfield in Gloucestershire, where the Reverend William Hazlitt had accepted a new pastorate after his marriage. In 1770, the elder Hazlitt accepted yet another position and moved with his family to Maidstone, Kent, where his first and only surviving daughter, Margaret (usually known as "Peggy"), was born that year.[1]

Childhood

William, the youngest of these, was born in Mitre Lane, Maidstone, in 1778. In 1780, when he was two, his family began a migratory existence that was to last several years. From Maidstone his father took them to Bandon, County Cork, Ireland; and from Bandon in 1783 to America, where Mr. Hazlitt preached, lectured, and founded the First Unitarian Church at Boston. In 1786-1787 the family returned to England and took up their abode at Wem, in Shropshire. The elder son, John, was now old enough to choose a vocation, and became a miniature-painter. The second child, Peggy, had begun to paint also, amateurishly in oils. William, aged eight—a child out of whose recollection all memories of Bandon and of America (save the taste of barberries) soon faded—took his education at home and at a local school.

Education

His father intended him for the Unitarian ministry, and in 1793 sent him to a seminary on what was then the outskirts of London, the New Unitarian College at Hackney (commonly referred to as Hackney College).[2] He stayed there for only about two years,[3] but during that time the young Hazlitt read widely and formed habits of independent thought and respect for the truth that remained with him for life, the tutelage at Hackney having been strongly influenced by eminent Dissenting thinkers of the day like Richard Price and Joseph Priestley.[4] Shortly after returning home, William decided to become a painter, a decision inspired somewhat by his brother's career. He alternated between writer and painter, proving himself proficient in both fields, until finally he decided that the financial and intellectual rewards of painting were outweighed by those of writing and he left it behind as a career.

Adulthood

In 1798 Hazlitt was introduced to Samuel Taylor Coleridge and William Wordsworth. He was also interested in art, and visited his brother John, who was now apprenticed to Sir Joshua Reynolds. He became friendly with Charles and Mary Lamb, and in 1808 he married Sarah Stoddart, who was a friend of Mary, and sister of John Stoddart, editor of The Times. They lived at Winterslow in Salisbury, but after three years he left her and began a journalistic career, writing for the Morning Chronicle, Edinburgh Review, The London Magazine, and The Times. He published several volumes of essays, including The Round Table and Characters of Shakespear's Plays, both in 1817. His best-known work is The Spirit of the Age (1825), a collection of portraits of his contemporaries, including Lamb, Coleridge, Wordsworth, Lord Byron, Jeremy Bentham, and Sir Walter Scott.

Famous for never losing his revolutionary principles, Hazlitt attacked those he saw as 'apostates' with the most rigor, seeing their move towards conservatism as a personal betrayal. He felt admiration for Edmund Burke as a thinker and writer but deemed him to have lost all common sense when his politics turned more conservative. He admired the poetry of Coleridge and Wordsworth (he continued to quote especially Wordsworth's poetry long after he had broken off friendly contact with either); but he directed some of his most vitriolic attacks against them for having replaced the humanistic and revolutionary ideas of their earlier years with staunch support of the Establishment. His harshest criticism was reserved for the revolutionary-turned-poet-laureate Robert Southey. He became romantically attached to Sarah Walker, a maid at his lodging house, which caused him to have something of a breakdown and publish details of their relationship in an 1823 book, Liber Amoris: Or, The New Pygmalion. This was seized upon by the right-wing press and was used to destroy his distinguished journalistic career with scandal. The most vitriolic comment directed towards Hazlitt was by the essayist Thomas Love Peacock, a former supporter turned rival, who declared Liber Amoris to be the "incoherent musings of a sometime polemicist turned full-time libertine and whore-master."

Hazlitt is credited with having created the denomination Ultracrepidarianism to describe one who gives opinions on matters beyond one's knowledge.

Hazlitt put forward radical political thinking which was proto-socialist and well ahead of his time and was a strong supporter of Napoleon Bonaparte, writing a four-volume biography of him. He had his admirers, but was so against the institutions of the time that he became further and further disillusioned and removed from public life. He died in poverty on September 18, 1830, and is buried in St. Anne’s Churchyard, Soho, London.

Legacy

His works having fallen out of print, Hazlitt underwent a small decline, though in the late 1990s his reputation was reasserted by admirers and his works reprinted. Two major works then appeared,The Day-Star of Liberty: William Hazlitt's Radical Style by Tom Paulin in 1998 and Quarrel of the Age: the life and times of William Hazlitt by A. C. Grayling in 2000.

In 2003, following a lengthy appeal, Hazlitt's gravestone was restored in St. Anne's Churchyard, unveiled by Michael Foot. A Hazlitt Society was then inaugurated.

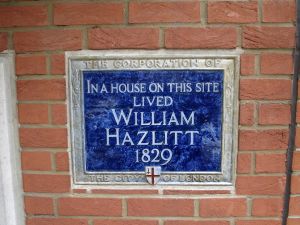

One of Soho's fashionable hotels is named after the writer. Hazlitt's hotel located on Frith Street is one of the homes William lived in and still today still retains much of the interior he would have known so well.

Works

- An Essay on the Principles of Human Action (1805)

- Lectures on the Literature of the Age of Elizabeth and Characters of Shakespear's Plays (1817)

- Lectures on the English Poets (1818)

- Lectures on the English Comic Writers (1819)

- Liber Amoris: Or, The New Pygmalion (1823)

- The Spirit of the Age (1825)

- On The Pleasure of Hating (c.1826)

Quotes

- The love of liberty is the love of others; the love of power is the love of ourselves.

- The essence of poetry is will and passion.

- Rules and models destroy genius and art.

- Man is the only animal that laughs and weeps, for he is the only animal that is struck with the difference between what things are and what they ought to be.

- The Tory is one who is governed by sense and habit alone. He considers not what is possible, but what is real; he gives might the preference over right. He cries long life to the conqueror, and is ever strong upon the stronger side – the side of corruption and prerogative.

- —from Introduction to Political Essays, 1817.

- Hazlitt writes about Samuel Taylor Coleridge

- "I had no notion then that I should ever be able to express my admiration to others in motley imagery or quaint allusion, till the light of his genius shone into my soul, like the sun's rays glittering in the puddles of the road. I was at that time dumb, inarticulate, helpless, like a worm by the way-side, crushed, bleeding lifeless; but now, bursting from the deadly bands that 'bound them,

- 'With Styx nine times round them,'

- "my ideas float on winged words, and as they expand their plumes, catch the golden light of other years. My soul has indeed remained in its original bondage, dark, obscure, with longing infinite and unsatisfied; my heart, shut up in the prison-house of this rude clay, has never found, nor will it ever find, a heart to speak to; but that my understanding also did not remain dumb and brutish, or at length found a language to express itself, I owe to Coleridge."

- —from the essay "My First Acquaintance with Poets"

- "For if no man can be happy in the free exercise of his reason, no wise man can be happy without it."

- —from the essay "On the Periodical Essayists"

Notes

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Baker, Herschel. William Hazlitt. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1962. OCLC 23967435

- Bromwich, David. Hazlitt, the mind of a critic. New York; Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983. ISBN 9780195033434

- Hazlitt, William. The letters of William Hazlitt. New York: New York University Press, 1978. ISBN 9780814749876

- Uphaus, Robert W. William Hazlitt. Boston, Mass.: Twayne, 1985. ISBN 9780805769043

- Wardle, Ralph M. Hazlitt. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1971. ISBN 9780803207905

External links

All links retrieved February 12, 2014.

- Works by William Hazlitt. Project Gutenberg.

- Essays by William Hazlitt at Quotidiana.org

- Hazlitt Society official site

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.