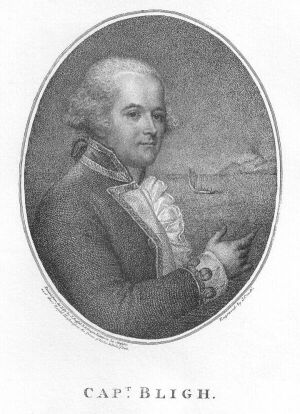

William Bligh

Vice-Admiral William Bligh FRS RN (September 9, 1754 – December 7, 1817) was an officer of the British Royal Navy and colonial administrator. He is best known as "Captain Bligh" for the Mutiny on the Bounty that occurred against his command, and the remarkable voyage he made to the island of Timor, after being set adrift by the mutineers in the Bounty's launch. Many years after the mutiny on the ''Bounty'', he was appointed Governor of New South Wales (Australia), with a brief to clean up the corrupt rum trade of the NSW Corps. He had some success in his task but quickly faced opposition, which culminated in the Rum Rebellion led by Major George Johnston working closely with John Macarthur.

Although Bligh was certainly not the vicious man portrayed in popular fiction, some claim his over-sensitivity and acid tongue damaged what would have otherwise been a distinguished career. Bligh is most famous for having suffered three mutinies, which is a somewhat negative reason for fame. However, his navigational skills in charting previously unknown (to Europeans) Pacific islands did make a significant contribution to extending British influence, communications and travel, in the region. His interest in the cultures and languages of the islands, too, earned him a Fellowship of the Royal Society. Bligh was hampered by chronic inability to master relationship with his subordinates, yet he still achieved high rank. His legacy has enigmatic aspects, which is perhaps another reason why his story remains one of interest to creators of fiction as well as to historians of this period when European interests were expanding around the globe.

Early life

Bligh was the son of Francis and Jane Bligh (née Balsam) in Plymouth, Devon, although of a Cornish family. He was signed up for the Royal Navy in 1761, at the age of seven, in the same city. Whether he went to sea at this tender age is doubtful, as it was common practice to sign on a "young gentleman" simply in order to rack up the required years of service for quick promotion. In 1770, at the age of 16, he joined HMS Hunter as an able seaman, the term being used only because there was no vacancy for a midshipman. He became a midshipman early in the following year of 1771.

In September 1771, Bligh was transferred to the Crescent and remained on that ship for three years.

In 1776, Bligh was selected by Captain James Cook for the position of Sailing Master on the Resolution and accompanied Captain Cook in July 1776 on Cook's third and fatal voyage to the Pacific. He reached England again at the end of 1780 and was able to give further details of Cook's last voyage.

Bligh married Elizabeth Betham, the daughter of a Customs Collector, on February 4, 1781, at the age of 26. The wedding took place at Onchan, on the Isle of Man (coincidentally Fletcher Christian was descended from a Manx family). A few days later, he was appointed to serve on HMS Belle Poule as its master. Soon after this, in August 1781, he fought in the Battle of Dogger Bank under Admiral Parker. For the next 18 months, he was a lieutenant on various ships. He also fought with Lord Howe at Gibraltar in 1782.

Between 1783 and 1787, Bligh was a captain in the merchant service.

In 1787 Bligh was selected as commander of HMAV Bounty.

Bligh would eventually rise to the rank of Vice Admiral in the British Royal Navy.

William Bligh's naval career consisted of a variety of appointments and assignments. A summary is as follows:

| Date(s) | Rating | Ship |

|---|---|---|

| 1 July 1761–21 February 1763 | Ship's Boy and Captain's Servant | HMS Monmouth (64) |

| 27 July 1770 | Able Seaman | HMS Hunter (10) |

| 5 February 1771 | Midshipman | HMS Hunter |

| 22 September 1771 | Midshipman | HMS Crescent (28) |

| 2 September 1774 | Able Seaman | HMS Ranger |

| 30 September 1775 | Master's Mate | HMS Ranger |

| 20 March 1776–October 1780 | Master | HM Sloop Resolution (12) |

| 14 February 1781 | Master | HMS Belle Poule |

| 5 October 1781 | Lieutenant | HMS Berwick (74) |

| 1 January 1782 | Lieutenant | HMS Princess Amelia (80) |

| 20 March 1782 | Lieutenant | HMS Cambridge (80) |

| 14 January 1783 | Joins Merchant Service | |

| 1785 | Commanding Lieutenant | Merchant Vessel Lynx |

| 1786 | Lieutenant | Merchant Vessel Britannia |

| 1787 | Returns to Royal Navy | |

| 16 August 1787 | Lieutenant | HMAV Bounty |

| 14 November 1790 | Commander | HMS Falcon (14) |

| 15 December 1790 | Commander | HMS Medea (28) |

| 16 April 1791–1793 | Commander | HMS Providence |

| 16 April 1795 | Commander | HMS Calcutta (24) |

| 7 January 1796 | Captain | HMS Director (64) |

| 18 March 1801 | Captain | HMS Glatton (56) |

| 12 April 1801 | Captain | HMS Monarch (74) |

| 8 May 1801–28 May 1802 | Captain | HMS Irresistible (74) |

| Peace of Amiens (March 1802–May 1804) | ||

| 2 May 1804 | Captain | HMS Warrior (74) |

| 14 May 1805 | Appointed Governor of New South Wales | |

| 27 September 1805 | Captain | HMS Porpoise (12), voyage out to NSW |

| Governor of NSW 13 August 1806–26 January 1808 | ||

| 31 July 1808 | Commodore | HMS Porpoise (12), Tasmania |

| 3 April 1810–25 October 1810 | Commodore | HMS Hindostan (50), returning to England. |

| 31 July 1811 | Appointed Rear Admiral of the Blue (backdated to 31 July 1810) | |

| 4 June 1814 | Appointed Vice Admiral of the Blue | |

The voyage of the Bounty

In 1787, Bligh took command of the Bounty. In order to win a premium offered by the RSA he first sailed to Tahiti to obtain breadfruit trees, then set course for the Caribbean, where breadfruit was wanted for experiments to see whether it would be a successful food crop for slaves there. The Bounty never reached the Caribbean, as mutiny broke out on board shortly after leaving Tahiti. In later years, Bligh would repeat the same voyage that the Bounty had undertaken and would eventually succeed in delivering the breadfruit to the West Indies.

Bligh's mission may have introduced the Ackee to the Caribbean as well, though this is uncertain (Ackee is now called Blighia sapida in binomial nomenclature, after Bligh).

The voyage was difficult. After trying unsuccessfully for a month to round Cape Horn, the Bounty was finally defeated by the notoriously stormy weather and forced to take the long way around the Cape of Good Hope. That delay resulted in a further delay in Tahiti, as they had to wait 5 months for the breadfruit plants to mature enough to be transported. The Bounty departed Tahiti in April 1789.

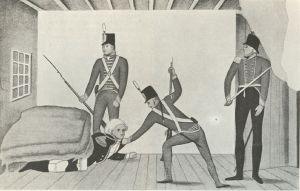

Since it was rated only as a cutter, the Bounty had no officers other than Bligh himself (who was then only a lieutenant), a very small crew, and no Marines to provide protection from hostile inhabitants during stops or to enforce security on board ship. To allow longer uninterrupted sleep, Bligh divided his crew into three watches instead of two, and placed his protege Fletcher Christian — rated as a Master's Mate — in charge of one of the watches. The mutiny, which broke out during the return voyage on April 28, 1789, was led by Christian and supported by a third of the crew, who had seized firearms during Christian's night watch and then surprised and bound Bligh in his cabin. Despite being in the majority, none of the loyalists seemed to have put up any significant struggle once they saw Bligh bound, and the ship was taken bloodlessly. The mutineers provided Bligh and the 18 of his crew who remained loyal with a 23 foot (7 m) launch (so heavily loaded that the sides were only a few inches above the water), with four cutlasses and food and water for a few days to reach the most accessible ports, a sextant and a pocket watch, but no charts or compass. The launch could not hold all the loyal crew members, and four were detained on the Bounty by the mutineers for their useful skills; these were later released at Tahiti.

Tahiti was upwind from Bligh's initial position, and was the obvious destination of the mutineers. Many of the loyalists claimed to have heard the mutineers cry "Huzzah for Otaheite!" as the Bounty pulled away. Timor was the nearest European outpost. Bligh and his crew did make for Tofua first, to obtain supplies. There they were attacked by hostile natives and a crewman was killed. After fleeing Tofua, Bligh didn't dare stop at the next islands (the Fiji islands), as he had no weapons for defense and expected further hostile receptions.

Bligh had a well-deserved confidence in his navigational skills, which he had perfected under the instruction of Captain Cook. His first responsibility was to survive and get word of the mutiny as soon as possible to British vessels that could pursue the mutineers. Thus, he undertook the seemingly-impossible 3618 nautical mile (6701 km) voyage to Timor. In this remarkable act of seamanship, Bligh succeeded in reaching Timor after a 47-day voyage, with the only casualty being the crewman killed on Tofua. Ironically, several of the men who survived this ordeal with him soon died of sickness, possibly malaria, in the pestilential Dutch East Indies port of Batavia, as they waited for transport to England.

Reasons for the Mutiny

To this day, the reasons for the mutiny are a subject of considerable debate. Some believe that Bligh was a cruel tyrant whose abuse of the crew led members of the crew to feel that they had no choice but to take the ship from Bligh. Others believe that the crew, inexperienced and unused to the rigors of the sea and, after having been exposed to freedom and sexual excess on the island of Tahiti, refused to return to the "Jack Tars" existence of a seaman. They were "led" by a weak Fletcher Christian and were only too happy to be free from Bligh's acid tongue. They believe that the crew took the ship from Bligh so that they could return to a life of comfort and pleasure on Tahiti.

Bligh returned to London arriving in March 1790.

The Bounty's log shows that Bligh resorted to punishments sparingly. He scolded when other captains would have whipped; and he whipped when other captains would have hanged. He was an educated man, deeply interested in science, convinced that good diet and sanitation were necessary for the welfare of his crew. He took a great interest in his crew's exercise, was very careful about the quality of their food, and insisted upon the Bounty being kept very clean. His personal morals were above reproach. He cared about the natives of Tahiti and tried (unsuccessfully) to check the spread of venereal disease among them. The flaw in this otherwise enlightened naval officer was, as J.C. Beaglehole wrote: "[Bligh made] dogmatic judgements which he felt himself entitled to make; he saw fools about him too easily… thin-skinned vanity was his curse through life…. [Bligh] never learnt that you do not make friends of men by insulting them." [1]. Bligh does appear to have had difficulty relating to those who served under him, and to have invaded the privacy of the crew that they needed to cope with the demands of life at sea, and by refusing their rum ration.

On the Bounty's launch, with a hopeless journey ahead of him and obliged to navigate by memory, Bligh was in his element. In the face of disaster, his courage and leadership made him capable of great things. He could rally his crew around him, and save the lives of them all. It was routine circumstances in fair weather that caused his "thin-skinned vanity" to make him temperamental and acid-tongued. Bligh's tongue-lashings over petty matters were feared far more than his infrequent lashings with a whip.

Popular fiction often confuses Bligh with Edward Edwards of the HMS ''Pandora'', who was sent on the Royal Navy's expedition to find the mutineers and bring them to trial. Edwards was every bit the cruel man that Bligh was accused of being; the 14 men that he captured were confined in terrible conditions. When the Pandora ran aground on the Great Barrier Reef, four of the prisoners and 31 of the crew were killed. The prisoners would have all perished, had not some unknown crewman, more compassionate than Edwards, unlocked their cage before fleeing the doomed vessel.

In October 1790, Bligh was honorably acquitted at the court-martial inquiring the loss of the Bounty. Shortly thereafter, Bligh's book called A Narrative of the Mutiny on board His Majesty's Ship "Bounty" was published.

Of the ten surviving prisoners, four were acquitted, due to Bligh's testimony that they were non-mutineers that Bligh was obliged to leave on the Bounty due to lack of space in the launch. Two others were convicted because, while not participating in the mutiny, they were passive and did not resist. They subsequently received royal pardons. One was convicted but excused on a technicality. The remaining three were convicted and hanged.

Bligh's Letter to his Wife

The following is a letter to Bligh's wife, written from Coupang, Dutch East Indies, (circa June 1791) in which the first reference to events on the Bounty is mentioned.

- My Dear, Dear Betsy,

- I am now in a part of the world I never expected, it is however a place that has afforded me relief and saved my life, and I have the happiness to assure you that I am now in perfect health…

Know then my own Dear Betsy, that I have lost the Bounty …on the 28th April at day light in the morning Christian having the morning watch. He with several others came into my Cabin while I was a Sleep, and seizing me, holding naked Bayonets at my Breast, tied my Hands behind my back, and threatened instant destruction if I uttered a word. I however call'd loudly for assistance, but the conspiracy was so well laid that the Officers Cabbin Doors were guarded by Centinels, so Nelson, Peckover, Samuels or the Master could not come to me. I was now dragged on Deck in my Shirt & closely guarded—I demanded of Christian the case of such a violent act, & severely degraded for his Villainy but he could only answer—"not a word sir or you are Dead." I dared him to the act & endeavored to rally some one to a sense of their duty but to no effect…

The Secrisy of this Mutiny is beyond all conception so that I can not discover that any who are with me had the least knowledge of it. Even Mr. Tom Ellison took such a liking to Otaheite [Tahiti] that he also turned Pirate, so that I have been run down by my own Dogs…

My misfortune I trust will be properly considered by all the World—It was a circumstance I could not foresee—I had not sufficient Officers & had they granted me Marines most likely the affair would never have happened—I had not a Spirited & brave fellow about me & the Mutineers treated them as such. My conduct has been free of blame, & I showed everyone that, tied as I was, I defied every Villain to hurt me…

I know how shocked you will be at this affair but I request of you My Dear Betsy to think nothing of it all is now past & we will again looked forward to future happyness. Nothing but true consciousness as an Officer that I have done well could support me…. Give my blessings to my Dear Harriet, my Dear Mary, my Dear Betsy & to my Dear little stranger* & tell them I shall soon be home… To You my Love I give all that an affectionate Husband can give—

Love, Respect & all that is or ever will be in the power of your

ever affectionate Friend and Husband Wm Bligh.[2]

The Bligh's fourth child, another daughter, born a few months after Lt. Bligh sailed from England

After the Bounty

After a court of inquiry, Bligh continued to sail in the British navy.

In 1797 Bligh was one of the captains whose crews mutinied against over "issues of pay and involuntary service for common seamen" during the Spithead mutiny.[3] Despite receiving some of their demands at Spithead, disputes over navy life continued among the common sailor. Bligh was again one of the captains effected during the mutiny at the Royal Navy anchorage of Nore. "Bligh became more directly involved in the Nore Mutiny," which "failed to achieve its goals of a fairer division of prize money and an end to brutality."[3] It should be noted that these events were not triggered by any specific actions by Bligh as they "were widespread, [and] involved a fair number of English ships".[3] It was at this time that he learned "that his common nickname among men in the fleet was 'that Bounty Bastard'."[3]

Bligh went on to serve under Admiral Nelson at the Battle of Copenhagen on April 2, 1801. Bligh commanded the HMS Glatton, a 56-gun ship of the line, which was experimentally fitted exclusively with carronades. After the battle, Bligh was personally praised by Nelson for his contribution to the victory. He sailed the Glatton safely between the banks while three other vessels ran aground. When Nelson feigned not to notice the signal 43 from Admiral Parker, to stop the battle and kept the signal 16 hoisted to continue the engagement, Bligh was the only captain who could see the conflicting two signals. By choosing to also display Nelson's signal, he ensured that all the vessels behind him kept fighting.

As captain of HMS Director, at the Battle of Camperdown, Bligh engaged three Dutch vessels: the Haarlem, the Alkmaar and the Vrijheid. While the Dutch suffered serious casualties, only 7 seamen were wounded on the Director.

Governor of New South Wales

Bligh was offered the position of Governor of New South Wales by Sir Joseph Banks and appointed in March 1805, at £2,000 per annum, twice the pay of the retiring Governor Philip Gidley King. He arrived in Sydney in August 1806, to become the fourth governor. There he suffered another mutiny, the Rum Rebellion, when, on 26 January 1808, the New South Wales Corps under Major George Johnston marched on government house and arrested him. He sailed to Hobart on the Porpoise, failed to gain support to retake control of the colony and remained effectively imprisoned on board from 1808 until January 1810.

Bligh sailed from Hobart and arrived in Sydney on 17 January 1810 to collect evidence for the upcoming court-martial of Major George Johnston. He departed for the trial in England aboard the Porpoise on 12th May and arrived on 25 October 1810. The court-martial cashiered Johnston from the Marine Corps and British armed forces.

Afterwards, Bligh's promotion to Rear Admiral was backdated, and 3 years later, in 1814, he was promoted again, to Vice Admiral of the Blue.

Bligh designed the North Bull Wall at the mouth of the River Liffey in Dublin, to ensure the entrance to Dublin Port did not silt up by a sandbar forming.

Bligh died in Bond Street, London on 6 December 1817 and was buried in a family plot at St. Mary's, Lambeth. This church is now the Museum of Garden History. His tomb, notable for its use of Coade stone, is topped by a breadfruit. A plaque marks Bligh's house, one block east of the Museum.

Legacy

Although cleared of any wrongdoing and awarded high rank before his retirement, Bligh, rightly or wrongly, is mainly remembered as a man against whom his crews and soldiers mutinied. His reputation as a disciplinarian appears to be ill earned; indeed, what caused his downfall was inability to control his men. On the other hand, while Governor of New South Wales he did much to combat corruption. His exlorations also added to Europe's knowledge of the Pacific where he charted a number of islands previously unknown to Europeans, and his interest in the culture of the people of the Pacific earned him the Fellowship of the Royal Society. His navigatinal skill did help to make the world a smaller place. However, as his legacy has been depicted in the popular media, it raises questions about whether rebellion agianst weak leadership is not sometimes justified, even though mutiny remains anathema to military dsicipline, which depends on respect for the chain of command.

See also

Notes

- ↑ cited in "William Bligh" Encyclopedia of World Biography William Bligh Retrieved September 13, 2007

- ↑ Caroline Alexander. The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty. (NY: Viking Penguin, 2003), 154-156

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 "William Bligh-Vice Admiral of the Blue," BBC 7 June 2005 William Bligh - Vice Admiral of the Blue Retrieved September 13, 2007.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Alexander, Caroline. The Bounty: The True Story of the Mutiny on the Bounty. NY: Viking Penguin, 2003 ISBN 067003133X.

- Dening, Greg. Mr Bligh's Bad Language: passion, power and theatre on the Bounty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992 ISBN 0521467187.

- Dictionary of Australian Biography William Bligh [1]. Retrieved September 13, 2007.

- Kennedy, Gavin. Bligh. Gerald Dockworth & Co. Ltd., 1978 ISBN 9780715609576

- Lloyd, Christopher. St. Vincent & Camperdown. London: B.T. Batsford Ltd., 1963.

- McKinney, Sam. Bligh: A True Account of the Mutiny Abord His Majesty's Ship Bounty. Camden, ME: International Marine Publishing Company, 1989 ISBN 0877429812

- Mackaness, George. The life of Vice-Admiral William Bligh, R.N., F.R.S., New and rev. ed. Sydney: Angus and Robertson, 1951.

- Conway, Christiane. Letters from the Isle of Man - The Bounty-Correspondence of Nessy and Peter Heywood. Onchan, Isle of Man: The Manx Experience, 2005 ISBN 187312077X.

- Schreiber, Roy. Captain Bligh's Second Chance: An eyewitness account of his return to the south seas by Lt George Tobin. London: Chatham, 2007 ISBN 9781861762801

External links

All links retrieved October 2, 2020.

- A Narrative Of The Mutiny, On Board His Majesty's Ship Bounty, 1790. Projectt Gutenberg.

- A Voyage to the South Sea, 1792. Project Gutenberg.

- A. G. L. Shaw, 'Bligh, William (1754 - 1817)', Australian Dictionary of Biography, Volume 1, MUP, 1966, pp 118-122.

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by: Philip Gidley King |

Governor of New South Wales 1806-1808 |

Succeeded by: Lachlan Macquarie |

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.