Vladimir I of Kiev

| Saint Vladimir of Kiev | |

|---|---|

Vladimir I of Kiev | |

| Grand Prince of Kiev | |

| Born | c. 950 |

| Died | 1015 |

| Major shrine | St Volodymyr's Cathedral, Kiev |

| Feast | July 15 |

| Attributes | crown, cross, throne |

Vladimir Svyatoslavich the Great (c. 958 – July 15, 1015, Berestovo), also known as Saint Vladimir of Kiev, was the grand prince of Kiev who converted to Christianity in 987 and is generally credited as the person most responsible for the Christianization of Russia.

The illegitimate son of Prince Sviatoslav I of Kiev, Vladmir consolidated the Kievan Rus' from the Ukraine to the Baltic Sea through his military exploits. During his early reign, he remained a zealous pagan, devoting himself to the Slavic-Norse deities, establishing numerous temples, and practicing polygamy. In 987, however, he converted to Christianity as a condition of a marriage alliance with Anna, the daughter of the Byzantine Emperor Basil II. He then ordered the conversion of Kiev and Novgorod to the Orthodox Church and began the destruction of other faiths.

After his conversion, and with the Byzantine Empire now his ally, Vladimir was able to live for the most part in peace with his neighbors and devote new resources to education, legal reform, and charitable works. The Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox churches celebrate the feast day of St. Vladimir on July 15. A large number of legends and Russian folk songs were written in Vladimir’s memory.

Way to the throne

Vladimir was the youngest son of Sviatoslav I of Kiev by his housekeeper Malusha, described in the Norse sagas as a prophetess who lived to the age of 100 and was brought from her cave to the palace to predict the future. Malusha's brother Dobrynya was Vladimir's tutor and most trusted adviser. Hagiographic tradition also connects his childhood with the name of his paternal grandmother, Olga of Kiev, who was a Christian and governed the capital during Sviatoslav's frequent military campaigns. The efforts of Olga to convert her son, Sviatoslaff, to Christianity were unsuccessful, but the seeds of her Christianity—either directly or through spiritual influence—are believed to have born fruit in Vladimir's later life.

Transferring his capital to Preslavets in 969, Sviatoslav designated Vladimir as ruler of Veliky Novgorod between the modern cities of Moscow and Saint Petersburg. However, he gave the key city of Kiev to his legitimate son Yaropolk. After Sviatoslav's death in 972, a fratricidal war erupted between Yaropolk and his younger brother Oleg, who ruled the Slavic tribe known as the Drevlians in Ukraine on the west bank of the Dnieper River, in 976. As a result of the fighting, Vladimir was forced to flee from Novgorod. He went to his kinsmen, Haakon Sigurdsson, the ruler of Norway in 977, and gathered as many of the Viking warriors as he could to assist him to recover Novgorod, and on his return the next year marched against Yaropolk.

On his way to Kiev, Vladimir sent ambassadors to Rogvolod (Norse: Ragnvald), prince of Polotsk, to sue for the hand of his daughter Rogneda (Norse: Ragnhild). This noble princess at first refused to engage herself to a prince of illegitimate birth. However, when Vladimir attacked Polotsk and slew Rogvolod, Rogneda was left with no choice. Polotsk was also a key fortress on the way to Kiev, and the capture of this city together with Smolensk facilitated Vladimir's taking of Kiev in 980, where he slew Yaropolk and was proclaimed konung (king) of all Kievan Rus.

In addition to gaining control of his father's extensive domain, Vladimir continued to expand his territories substantially. In 981 he conquered the central European Cherven cities, in modern Galicia. In 983, he subdued the Yatvingians, whose territories lay between Lithuania and Poland. In 985, he led a fleet along the central rivers of Russia to conquer the Bulgars of the Kama, planting numerous fortresses and colonies on his way.

Though Christianity had won many converts since his grandmother Olga's time, Vladimir had remained a pagan. He reportedly took 800 concubines, besides seven wives and erected various statues and shrines to pagan gods. However, some sources indicate that he was already interested in using religion as a unifying force in his kingdom, and that he attempted to reform Slavic paganism by establishing the Slavic thunder-god Perun as a supreme deity.

Baptism of the Rus'

Valdimir's conversion

Russian Primary Chronicle, a history of the Kievan Rus from around 850 to 1110, reports that in the year 987, Vladimir sent envoys to study the religions of the various neighboring nations whose representatives had been urging him to embrace their respective faiths. The result was described in legendary terms by the chronicler Nestor. According to this version, the envoys reported of the Muslim Bulgarians of the Volga there was no gladness among them, "only sorrow and a great stench," and that their religion was undesirable due to its taboo against alcoholic beverages and pork. Vladimir immediately rejected this religion, saying: "Drinking is the joy of the Rus'." Russian sources also describe Vladimir as consulting with Jews, who may or may not have been Khazars, ultimately rejecting their religion, because their loss of Jerusalem was evidence of their having been abandoned by God. Ultimately, Vladimir settled on Christianity.

In the Catholic churches of the Germans Vladimir's emissaries saw no beauty. On the other hand, at Constantinople, the ritual and beautiful architecture of the Orthodox Church deeply impressed them. "We no longer knew whether we were in heaven or on earth," they reported, describing a majestic liturgy in Hagia Sophia. The splendor of the church itself was such that "we know not how to tell of it."

Vladimir was no doubt duly impressed by this account of his envoys, but may have been even more keenly aware of the political gains he would receive from the Byzantine alliance. In 988, having taken the Byzantine town of Chersonesos in Crimea, he boldly negotiated for the hand of the emperor Basil II's sister, Anna. Never had a Greek imperial princess married a "barbarian" before, as matrimonial offers of French kings and German emperors had been peremptorily rejected, and these, at least, were Christians. Indeed, to marry the 27-year-old princess off to a pagan Slav seemed impossible, especially given the rumors of his penchant for polygamy.

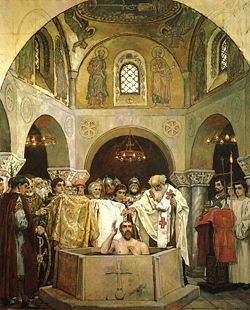

Vladimir was therefore baptized at Chersonesos, taking the Christian name of Basil as a compliment to his soon-to-be imperial brother-in-law. This sacrament was followed by his wedding with Anna. Returning to Kiev in triumph, he destroyed pagan monuments and established many churches, starting with the splendid Church of the Tithes (989) and monasteries on Mt. Athos.

Alternate account

Arab sources, both Muslim and Christian, present a more straightforward story of Vladimir's conversion. In this version, the Byzantine emperor Basil II faced a revolt in 987. Basil thus turned to the Rus' for assistance, even though they were considered enemies at that time. Vladimir agreed, but his price was the hand of the princess Anna. In return, he agreed to accept Orthodox Christianity as his religion and bring his people to the new faith. When the wedding arrangements were settled, Vladimir dispatched 6,000 troops to the Byzantine Empire and they helped to put down the revolt.

Later years and death

Returning to Kiev, Vladimir began the conversion of his people to Christianity. He formed a great council out of his boyars, and set twelve of his sons over his various principalities. He put away his former pagan wives and mistresses and destroyed pagan temples, statues, and holy sites. He built churches and monasteries and imported Greek Orthodox missionaries to educate his subjects. He also reportedly gave generously to various charitable works. After Anna's death, he married again, most likely to a granddaughter of the Holy Roman Emperor Otto the Great.

Not all of Vladimir's subjects accepted his policies peacefully, however. Among these were some of his former wives and their sons. Several of these princes rose in armed rebellion, notably Prince Yaroslav of Novgorod. In the course of putting down this revolt, Vladimir died in battle at Berestovo, near Kiev on July 15,

Legacy

Vladimir and his grandmother Olga are honored as the founders of Russian Christianity. After his death, he was immediately hailed my many as a saint and martyr. The various parts of his dismembered body were distributed among the numerous churches and monasteries he had founded and were venerated as relics. Many of these foundations remain key institutions in Russian Orthodoxy to this day.

St. Volodymyr's Cathedral in Kiev is dedicated to him, and the University of Kiev was originally named after him as the University of Saint Vladimir. There are also the Order of St. Vladimir in Russia and the Saint Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary in the United States. Dozens if not hundreds of Orthodox churches are named for Saint Vladimir the Great throughout the world.

Vladimir's memory was also kept alive by innumerable Russian folk ballads and legends, which refer to him as Krasno Solnyshko, that is, the Fair Sun. With him the Varangian (Norse) period of Eastern Slavic history ceases and the Christian period begins.

ReferencesISBN links support NWE through referral fees

- Boiselair, Georges. Saint Volodymyr the Beautiful Sun: Grand Prince of Kiev, 958-1015. Ukrainian millenium. Winnipeg: Volodymyr Pub. House, 1988. ISBN 9780920739655.

- Breck, John, John Meyendorff, and E. Silk. The Legacy of St. Vladimir: Byzantium, Russia, America. Crestwood, NY: St. Vladimir's Seminary Press, 1990. ISBN 978-0881410785.

- Butler, Francis. Enlightener of Rusʹ: The Image of Vladimir Sviatoslavich Across the Centuries. Bloomington, Ind: Slavica, 2002. ISBN 9780893572907.

- Korpela, Jukka. Prince, Saint, and Apostle: Prince Vladimir Svjatoslavič of Kiev, His Posthumous Life, and the Religious Legitimization of the Russian Great Power. Veröffentlichungen des Osteuropa-Institutes München, 67. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz, 2001. ISBN 9783447044578.

- Volkoff, Vladimir. Vladimir the Russian Viking. Woodstock, NY: Overlook Press, 1985. ISBN 9780879512347.

- This article incorporates text from the Encyclopædia Britannica Eleventh Edition, a publication now in the public domain.

External links

All links retrieved May 9, 2020.

- St. Vladimir the Great. newadvent.org

- St Vladimir's Orthodox Theological Seminary. svots.edu

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.