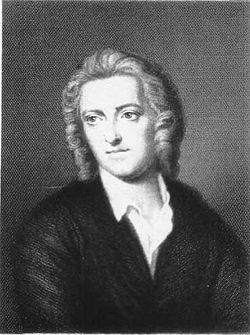

Thomas Gray

Thomas Gray (December 26, 1716 – July 30, 1771), was an English poet, classical scholar and professor of history at University of Cambridge. Although he produced a very small body of poetry, Gray is considered to be the most important poet of the middle decades of the 1700s, and possibly one of the most influential English poets in the eighteenth century as a whole. Gray's masterpiece, the lengthy "Elegy on a Country Churchyard," is universally seen as the highest achievement of eighteenth-century Classicism, as well as a major precursor and inspiration to the style of Romanticism. Gray was one of the most studious and fastidious of poets. His thorough knowledge of Classical Latin literature, as well as his considerable knowledge of older Anglo-Saxon traditions, infused his poetry with a masterful elegance of form while steering clear of the overly obscure tendencies of many other Classicially-inspired poets.

Gray's influence would extend to a number of other poets; most notably the Romantics Coleridge and Wordsworth would cite him as a major inspiration. Gray's poetry to be read and loved by thousands of readers to this day for its clarity, beauty, and melancholy grace. While many other English poets of the eighteenth century have fallen further and further into obscurity, Gray's popularity continues to endure.

Life

Thomas Gray was born in Cornhill, London. By all accounts, Gray's childhood was a terribly unhappy one, even though he was born into relative wealth. He was the only child of 12 to survive into adulthood, and his father was a notoriously violent man. When Gray's mother could no longer her endure her husband's abusiveness, she fled the home, taking young Thomas with her, supporting him by working as a hatmaker.

Gray was enrolled at Eton College in 1725, at the age of eight. At Eton, Gray soon distinguished himself as a studious, dedicated, and terribly shy student. He would gain the companionship at Eton of two equally precocious and delicate students, Horace Walpole, son of the Prime Minister and a future fiction-writer, and Richard West, another aspiring poet. Both West and Walpole would remain Gray's friends for life, and the small circle of like-minded friends they formed would become the kernel of the future literary movement known as the "Churchyard Poets."

Upon reaching adolescence, Gray became a Fellow at Cambridge University, first at Peterhouse and later at Pembroke College. Although he was an admirable student (he was particularly noted for his facility with Latin) Gray never received a degree from Cambridge, and in 1738 he left the institution to go on a Grand Tour of the European continent with Walpole, his childhood friend. Gray and Walpole spent two years traveling throughout France, Switzerland, and Italy, but towards the end of 1741, the pair had a falling-out, and Gray repaired for England. Apparently, Gray objected to Walpole's insistence that they spend large amounts of time at frivolous parties and social events, when Gray would rather be studying art, writing, and taking part in other, more solitary, activities.

In 1742, Gray settled near Cambridge. Richard West died the same year, and Gray, perhaps moved by this event, began to write poetry in English (prior to this time, he had, remarkably, written nearly all of his verse in Latin). Gray's studiousness paid dividends, and in 1742 he produced a flurry of dark, moving poems that established him immediately as one of the most formidable poets of the mid-eighteenth century, including "Ode On The Spring" and "Ode on a Distant Prospect of Eton College." Gray's style—deeply imbued with the Classicism popular in his times which he absorbed through his own studies of Latin—was markedly different from any other poetry produced up to that point in English for its emotional honesty, plainspokenness, and powerfully melancholy tone. It is exemplified in "Sonnet on the Death of Mr. Richard West:"

- In vain to me the smiling mornings shine,

- And reddening Phoebus lifts his golden fire;

- The birds in vain their amorous descant join;

- Or cheerful fields resume their green attire:

- These ears, alas! for other notes repine,

- A different object do these eyes require.

- My lonely anguish melts no heart but mine;

- And in my breast the imperfect joys expire.

- Yet morning smiles the busy race to cheer,

- And newborn pleasure brings to happier men:

- The fields to all their wonted tribute bear:

- To warm their little loves the birds complain:

- I fruitless mourn to him that cannot hear,

- And weep the more because I weep in vain.

Gray, however, attracted little critical attention with these early poems, and his efforts were made all the more difficult because of his own ruthless perfectionism. Gray was notorious for laboring endlessly over his poems, and it would not be until 1751, with the publication of "Elegy for a Country Churchyard"—a poem nearly 10 years in the making—that Gray would attain public recognition. The "Elegy" was an immediate success, notable not only for its beautiful language—it is considered by some to be the single most beautiful poem in English literature—but also for its innovative themes. Although written in the style of a classical elegy, Gray's poem is not just an elegy for the "rude forefathers of the village," but for all the peasants and working-men and lowlifes; indeed, it is an elegy for all mankind. Its humanistic themes, along with its melancholy overtones, would be a pre-cursor to the sort of sentimental poetry of the Romantics, and an entire pre-Romantic movement known as "The Churchyard Poets" would spring up out of Gray's "Elegy." Although too lengthy to be quoted in full, the following is an excerpt the poem's famous, opening lines:

- The curfew tolls the knell of parting day,

- The lowing herd wind slowly o'er the lea

- The plowman homeward plods his weary way,

- And leaves the world to darkness and to me.

- Now fades the glimm'ring landscape on the sight,

- And all the air a solemn stillness holds,

- Save where the beetle wheels his droning flight,

- And drowsy tinklings lull the distant folds;

- Save that from yonder ivy-mantled tow'r

- The moping owl does to the moon complain

- Of such, as wand'ring near her secret bow'r,

- Molest her ancient solitary reign.

- Beneath those rugged elms, that yew-tree's shade,

- Where heaves the turf in many a mould'ring heap,

- Each in his narrow cell for ever laid,

- The rude forefathers of the hamlet sleep.

- The breezy call of incense-breathing Morn,

- The swallow twitt'ring from the straw-built shed,

- The cock's shrill clarion, or the echoing horn,

- No more shall rouse them from their lowly bed.

- For them no more the blazing hearth shall burn,

- Or busy housewife ply her evening care:

- No children run to lisp their sire's return,

- Or climb his knees the envied kiss to share.

- Oft did the harvest to their sickle yield,

- Their furrow oft the stubborn glebe has broke;

- How jocund did they drive their team afield!

- How bow'd the woods beneath their sturdy stroke!

- Let not Ambition mock their useful toil,

- Their homely joys, and destiny obscure;

- Nor Grandeur hear with a disdainful smile

- The short and simple annals of the poor.

Although the "Elegy" made Gray into an instant celebrity, he continued to stay at Cambridge, working as a scholar and writing occasional verses. Most notably, in 1757, he published two odes in the style of Pindar, "The Progress of Poesy" and "The Bard," that were fiercely criticized as obscure. Gray was deeply hurt by the experience, and he never wrote anything of substantial length or merit for the remainder of his life. Instead, he devoted himself to his scholarly work in ancient Celtic and Scandinavian literatures, dying, in 1771, at the age of 55. He was buried at Stoke Poges, Buckinghamshire, the churchyard he had made famous in his "Elegy."

Legacy

Although Gray was one of the least productive poets (his collected works published during his lifetime amount to less than 1,000 lines), he is regarded as the predominant poetic figure of the middle decades of the eighteenth century in English literature. In 1757, following the resounding success of his "Elegy," he was offered the post of Poet Laureate, which he refused.

Gray's "Elegy" has become, far and away, his most memorable poem, and a lasting contribution to English literary heritage. It is still one of the most popular and most frequently quoted poems in the English language. As an example of its popularity, before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, British General James Wolfe is said to have recited it to his officers, adding: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec tomorrow."

Gray also wrote light verse, such as Ode on the Death of a Favourite Cat, Drowned in a Tub of Gold Fishes, concerning Horace Walpole's cat, which had recently died trying to fish goldfish out of a bowl. The poem moves easily to its double proverbial conclusion: "a fav'rite has not friend" and "know one false step is ne'er retrieved."

External links

All links retrieved April 30, 2023.

- The Thomas Gray Archive – Edited by Alexander Huber.

- The Elegy and the Internet by Gilbert Wesley Purdy; this essay provides considerable information on Thomas Gray, his influences and on the "Elegy Written in a Country Church-yard."

- Works by Thomas Gray. Project Gutenberg

Credits

New World Encyclopedia writers and editors rewrote and completed the Wikipedia article in accordance with New World Encyclopedia standards. This article abides by terms of the Creative Commons CC-by-sa 3.0 License (CC-by-sa), which may be used and disseminated with proper attribution. Credit is due under the terms of this license that can reference both the New World Encyclopedia contributors and the selfless volunteer contributors of the Wikimedia Foundation. To cite this article click here for a list of acceptable citing formats.The history of earlier contributions by wikipedians is accessible to researchers here:

The history of this article since it was imported to New World Encyclopedia:

Note: Some restrictions may apply to use of individual images which are separately licensed.